72nd Street station (IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line)

72 Street | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

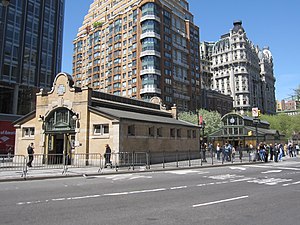

Original control house (left) and newer control house, located on opposite sides of 72nd Street | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Address | area of West 72nd Street, Broadway & Amsterdam Avenue New York, New York | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borough | Manhattan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Upper West Side | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°46′44.4″N 73°58′54.7″W / 40.779000°N 73.981861°W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Division | A (IRT)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | 1 2 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Structure | Underground | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 2 island platforms cross-platform interchange | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | October 27, 1904[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessible | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opposite- direction transfer | Yes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traffic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2023 | 9,086,110[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | 22 out of 423[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Control House on 72nd Street | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

New York City Landmark No. 1021 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MPS | Interborough Rapid Transit Subway Control Houses TR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NRHP reference No. | 80002684[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NYCL No. | 1021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Significant dates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Added to NRHP | May 6, 1980 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated NYCL | January 9, 1979[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

72nd Street Subway Station (IRT) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

New York City Landmark No. 1096 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MPS | New York City Subway System MPS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NRHP reference No. | 04001017[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NYCL No. | 1096 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Significant dates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Added to NRHP | September 17, 2004 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated NYCL | October 23, 1979[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 72nd Street station is an express station on the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line of the New York City Subway, located at the intersection of Broadway, 72nd Street, and Amsterdam Avenue in the Upper West Side neighborhood of Manhattan. It is served by the 1, 2, and 3 trains at all times.

The 72nd Street station was constructed for the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) as part of the city's first subway line, which was approved in 1900. Construction of the line segment that includes the 72nd Street station began on August 22 of the same year. The station opened on October 27, 1904, as one of the original 28 stations of the New York City Subway. The 72nd Street station's platforms were lengthened in 1960 as part of an improvement project along the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line. The station's only exit was originally through a head house in the median of Broadway south of 72nd Street. In 2002, the station was renovated and a second head house was built north of 72nd Street, within an expansion of Verdi Square.

The 72nd Street station contains two island platforms and four tracks. The outer tracks are used by local trains, while the inner two tracks are used by express trains. The station's original head house and part of its interior are New York City designated landmarks and are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The northern head house contains elevators, which make the station compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

History

[edit]Construction and opening

[edit]Planning for a subway line in New York City dates to 1864.[8]: 21 However, development of what would become the city's first subway line did not start until 1894, when the New York State Legislature passed the Rapid Transit Act.[8]: 139–140 The subway plans were drawn up by a team of engineers led by William Barclay Parsons, the Rapid Transit Commission's chief engineer. It called for a subway line from New York City Hall in lower Manhattan to the Upper West Side, where two branches would lead north into the Bronx.[7]: 3 A plan was formally adopted in 1897,[8]: 148 and all legal conflicts concerning the route alignment were resolved near the end of 1899.[8]: 161

The Rapid Transit Construction Company, organized by John B. McDonald and funded by August Belmont Jr., signed the initial Contract 1 with the Rapid Transit Commission in February 1900,[9] under which it would construct the subway and maintain a 50-year operating lease from the opening of the line.[8]: 165 In 1901, the firm of Heins & LaFarge was hired to design the underground stations.[7]: 4 Belmont incorporated the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) in April 1902 to operate the subway.[8]: 182

The 72nd Street station was constructed as part of the IRT's West Side Line (now the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line) from 60th Street to 82nd Street, for which work had begun on August 22, 1900. Work for that section had been awarded to William Bradley.[9] By late 1903, the subway was nearly complete, but the IRT Powerhouse and the system's electrical substations were still under construction, delaying the system's opening.[8]: 186 [10] As late as October 26, 1904, the day before the subway was scheduled to open, the walls and ceilings were incomplete.[11] The 72nd Street station opened on October 27, 1904, as one of the original 28 stations of the New York City Subway from City Hall to 145th Street on the West Side Branch.[2][8]: 186 The opening of the first subway line, and particularly the 72nd Street station, helped contribute to the development of the Upper West Side.[6]: 9 [12]: 380–381

1910s to 1930s

[edit]

After the first subway line was completed in 1908,[13] the station was served by local and express trains along both the West Side (now the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line to Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street) and East Side (now the Lenox Avenue Line). West Side local trains had their southern terminus at City Hall during rush hours and South Ferry at other times, and had their northern terminus at 242nd Street. East Side local trains ran from City Hall to Lenox Avenue (145th Street). Express trains had their southern terminus at South Ferry or Atlantic Avenue and had their northern terminus at 242nd Street, Lenox Avenue (145th Street), or West Farms (180th Street).[14] Express trains to 145th Street were later eliminated, and West Farms express trains and rush-hour Broadway express trains operated through to Brooklyn.[15][a]

To address overcrowding, in 1909, the New York Public Service Commission proposed lengthening the platforms at stations along the original IRT subway.[17]: 168 As part of a modification to the IRT's construction contracts made on January 18, 1910, the company was to lengthen station platforms to accommodate ten-car express and six-car local trains. In addition to $1.5 million (equivalent to $49.1 million in 2023) spent on platform lengthening, $500,000 (equivalent to $16.4 million in 2023) was spent on building additional entrances and exits. It was anticipated that these improvements would increase capacity by 25 percent.[18]: 15 At the 72nd Street station, the northbound platform was extended 80 feet (24 m) south and 25 feet (7.6 m) north, while the southbound platform was extended 25 feet (7.6 m) south and 100 feet (30 m) north. A new crossover and signal tower were also built in conjunction with these extensions.[18]: 110–111 Work progressed on the platform extensions at 72nd Street during 1910 and 1911.[19] Six-car local trains began operating in October 1910.[17]: 168 On January 23, 1911, ten-car express trains began running on the Lenox Avenue Line, and the following day, ten-car express trains were inaugurated on the West Side Line.[17]: 168 [20] The Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line opened south of Times Square–42nd Street in 1918, and the original line was divided into an H-shaped system. The original subway north of Times Square thus became part of the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line. Local trains (Broadway and Lenox Avenue) were sent to South Ferry, while express trains (Broadway and West Farms) used the new Clark Street Tunnel to Brooklyn.[21]

The original head house had two stairways to each platform, although a third stairway was added to the northbound platform at some point before 1924. In that year, it was proposed to build a third stairway to the southbound platform, and an exit-only staircase from the northbound platform to the traffic island just south of the head house; however, the Transit Bureau advised against this move as it would aggravate overcrowding.[22] In 1930, there was funding allocated to remove the station head house, and replace it with an underpass and sidewalk entrances.[23] In Fiscal Year 1937, space was cut out under parts of two staircases on the southbound platform to increase space for riders on the express side of the platform.[24] Funding was again allocated to remove the station house in 1945.[25]

1940s to 1960s

[edit]The city government took over the IRT's operations on June 12, 1940.[26][27] The IRT routes were given numbered designations in 1948 with the introduction of "R-type" rolling stock, which contained rollsigns with numbered designations for each service.[28] The Broadway route to 242nd Street became known as the 1, the White Plains Road (formerly West Farms) route as the 2, and the Lenox Avenue route as the 3.[29]

During the early 1950s, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA; now an agency of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, or MTA) considered converting the 59th Street–Columbus Circle station, a major transfer point to the IND Eighth Avenue Line, from a local stop to an express stop. This would serve the anticipated rise of ridership at the stop resulting from the under-construction New York Coliseum and the expected redevelopment of the area. In conjunction with that project, the NYCTA considered converting the 72nd Street station to a local station by walling off the express tracks from the platforms.[30] While the work was never completed, the firm Edwards, Kelcey and Beck was hired as Consulting Engineers in 1955 for the construction of the express station.[31]

The original IRT stations north of Times Square could barely fit local trains of five or six cars depending on the configuration of the trains. Stations on the line from Times Square to 96th Street, including this station but excluding the 91st Street station, had their platforms extended in the 1950s to 525 feet (160 m) to accommodate ten-car trains as part of a $100 million rebuilding program (equivalent to $1,084.8 million in 2023). The platforms at 72nd Street were extended in 1960,[32] and the track layout was changed accordingly.[33] Once the project was completed, all 1 trains became local and all 2 and 3 trains became express, and eight-car local trains began operation. Increased and lengthened service was implemented during peak hours on the 1 train on February 6, 1959.[34] Due to the lengthening of the platforms at 86th Street and 96th Street, the intermediate 91st Street station was closed on February 2, 1959, because it was too close to the other two stations.[35][33] In 1959, work was underway to install fluorescent lighting in the station.[36]

1970s and 1980s

[edit]In 1973, funding was allocated to study removing the headhouse and replacing it with sidewalk entrances.[37] The project would have created entrances on either sidewalk between 71st and 72nd Streets, connected to the platforms by a passageway under the tracks. The city government allocated a $1.35 million grant for the project, which was withdrawn in February 1976. Afterward, U.S. representative Bella S. Abzug continued to advocate for the station's renovation.[38] By 1979, there were plans to build a new station entrance and convert the existing headhouse into a newsstand.[39]

In the 1980s, the developers Abe Hirschfeld and Carlos Varsavsky pledged to spend $30 million renovating the 72nd Street station, in exchange for receiving the city government's approval for the nearby Lincoln West development.[40][41] When the developer Donald Trump took over the Lincoln West site in 1984, he said he would consider renovating the station but did not commit to the renovation.[42] In 1987, the founders of Ben & Jerry's proposed to spend $200,000 to $250,000 a year to maintain, clean, paint the station, install mosaics, and pipe in music into the station.[43] Though their proposal was supported by the MTA, the Transport Workers Union was opposed to the proposal as Ben & Jerry's wanted to hire non-union labor for the project.[44] The proposal had stalled by the end of 1987.[45] Ultimately, the contract expired at the end of March 1988.[44] Rather than adopting the 72nd Street station for maintenance, Ben & Jerry's chose to sponsor a theater of geese.[46]

From September 2 to 5, 1989, the station was closed so the station house could be reconfigured to reduce crowding at its northern end. The southern end of the station house was converted to an entrance, and two smaller token booths were installed, replacing the large token booth that blocked passenger flow through the middle of the station house. Turnstiles were moved to create separate fare control areas for northbound and southbound trains, eliminating free transfers between directions. In addition, the newsstand at the station house's northeastern corner was moved to the southwestern corner.[47][48] The lack of a free transfer between northbound and southbound trains persisted through the early 2000s.[49]

Renovation and 21st century

[edit]

By the late 20th century, the original configuration of the station was inadequate. Its only entrance was on the traffic island between Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue, and 71st and 72nd Streets. Furthermore, the platforms and stairways were unusually narrow; the platforms were 15.5 feet (4.7 m) wide at their widest point, and the staircases were 4 feet (1.2 m) wide.[50] When Donald Trump developed his Riverside South complex two blocks to the west in the 1990s, some locals opposed Trump's development, saying it would increase crowding at the 72nd Street station.[51][52] Following local residents' objections that the construction of Riverside South would worsen overcrowding at the station,[52] Trump agreed to give $5 million toward the station's renovation.[53] In October 1992, he offered to provide another $1 million for the station's expansion in exchange for the New York City Planning Commission's approval of his project.[54]

MTA officials announced in 1994 that they would spend $40 million to widen the platform.[55] To help fund the renovation, U.S. representative Jerry Nadler requested a $9.5 million grant from the federal government in 1994.[56] MTA officials subsequently rejected the renovation as being infeasible, saying the expense of digging through the bedrock to widen the platforms would have increased the project's total cost to $200 million.[55] Neighborhood groups protested the MTA's decision.[57] By February 1996, MTA officials were planning to award a $2 million design contract and a $55 million construction contract for the station renovation.[58] Dattner Architects and Gruzen Samton completed the design the same year.[59]

In 1998, New York City Transit's vice president for capital improvements, Mysore Nagaraja, said that a renovation of the 72nd Street station would commence after more important projects were completed.[60] The project was budgeted at $63 million,[61][62] and state assemblyman Scott Stringer successfully campaigned to have money allocated to the 72nd Street station's renovation.[63] The platforms would also be lengthened and a second entrance with elevators would be built.[62] Local residents objected that the renovations would not address the platforms' narrow width.[61][60] In February 1999, the MTA Board adopted a resolution allowing the MTA to use a request for proposals process for the project.[64]

Work on the project was initially slated to begin in March 2000, with an expected completion date of Summer 2003.[65] However, work on the project, which was to cost $53 million (equivalent to $93.8 million in 2023),[50] commenced in June 2000.[60] As part of the project, a secondary station house entrance with elevators was built north of 72nd Street. Each platform was lengthened by 50 feet (15 m), although the platforms largely remained the same width.[60] The work also involved permanently closing the northbound roadway of Broadway from 72nd to 73rd Streets, with northbound Broadway traffic being diverted onto Amsterdam Avenue.[66] Constructing the station house required taking a portion of Verdi Square, which required the replacement of the lost park space.[67] The original plan for the new station house would have included the use of vault lighting. However, in order to cut costs and deal with concerns over their maintenance, vault lighting was removed from the project.[68] The renovation was completed on October 29, 2002, providing a new, larger station house on the traffic island between 72nd and 73rd Streets and slightly wider platforms at the north end of the station.[69] The closeout of the project was done fourteen months late due to a setback in the installation of street lighting and acceptance by the New York City Department of Transportation.[70]

Landmark designations

[edit]The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the station house on the traffic island between 71st and 72nd Streets as a city landmark in January 1979.[5][39] The LPC chairman at the time said: "The subway kiosk is one of those irreplaceable amenities that do more than serve a useful function."[39] In October 1979, the LPC designated the space within the boundaries of the original station, excluding expansions made after 1904, as a city landmark.[7] The station was designated along with eleven others on the original IRT.[7][71] The original station house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 1980,[4] and the original interiors were listed on the NRHP in 2004.[6]

Station layout

[edit]

| Ground | Street level | Exit/entrance, fare control, station agent |

| Platform level | Northbound local | ← ← |

| Island platform | ||

| Northbound express | ← ← | |

| Southbound express | | |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound local | | |

72nd Street contains four tracks and two island platforms that allow for cross-platform interchanges between local and express trains heading in the same direction. Express trains run on the innermost two tracks, while local trains run on the outer pair.[72] The local tracks are used by the 1 at all times[73] and by the 2 during late nights;[74] the express tracks are used by the 2 train during daytime hours[74] and the 3 train at all times.[75] The next stop to the north is 79th Street for local trains and 96th Street for express trains. The next stop to the south is 66th Street–Lincoln Center for local trains and Times Square–42nd Street for express trains.[76] The 72nd Street station is fully wheelchair-accessible, with elevators connecting the street and platforms.[77]

The platforms were originally 350 feet (110 m) long, like at other express stations,[7]: 4 [78]: 9 and 15.5 feet (4.7 m) wide.[79][50][78]: 9 The station platforms were later lengthened, and by 1941 the southbound platform was 482 feet (147 m) long, with the center 340 feet (100 m) being 15.5 feet (4.7 m) wide. The platforms narrowed for 70 feet (21 m) on either side.[80] As a result of the 1958–1959 platform extension, both platforms became 520 feet (160 m) long.[33] From the southbound platform, two stairs go to the southern station house, while two stairs and one elevator lead to the northern station house. From the northbound platform, three stairs lead to the southern station house, while two stairs and one elevator lead to the northern station house.[6]: 16 The station is only 14 feet (4.3 m) below street level.[79][78]: 8–9

Design

[edit]As with other stations built as part of the original IRT, the station was constructed using a cut-and-cover method.[81]: 237 The tunnel is covered by a U-shaped trough that contains utility pipes and wires. The bottom of this trough contains a foundation of concrete no less than 4 inches (100 mm) thick.[6]: 3–4 [78]: 9 Each platform consists of 3-inch-thick (7.6 cm) concrete slabs, beneath which are drainage basins. The original platforms contain circular, cast-iron Doric-style columns spaced every 15 feet (4.6 m), while the platform extensions contain I-beam columns. Additional columns between the tracks, spaced every 5 feet (1.5 m), support the jack-arched concrete station roofs.[6]: 3–4 [7]: 4 [78]: 9 There is a 1-inch (25 mm) gap between the trough wall and the platform walls, which are made of 4-inch (100 mm)-thick brick covered over by a tiled finish.[6]: 3–4 [78]: 9

In the 72nd Street station, decorative elements are limited largely to the walls adjacent to the tracks, which are made of white glass tiles. The walls are divided by steel support columns every 5 feet (1.5 m); the panels between each set of columns are curved slightly away from the tracks.[7]: 9 [6]: 4 At 50-foot (15 m) intervals along the station walls, there are 5-by-8-foot (1.5 by 2.4 m) mosaic panels with blue, buff, and cream tiles in tapestry designs.[7]: 9 [6]: 4 [82] Atop each wall is a frieze with blue and buff mosaic tiles, with scrolled motifs protruding below the frieze band. The walls near the tracks do not have any identifying motifs with the station's name, as all station identification signs are on the platforms.[7]: 9 [6]: 4 There are some doorways along the trackside walls. At the platform staircases, the walls beneath the stairwell have white tile above brick wainscoting, while there are metal fences beside the stairwell.[6]: 4–5 The mosaic tiles at all original IRT stations were manufactured by the American Encaustic Tile Company, which subcontracted the installations at each station.[78]: 31 The decorative work was performed by tile contractor John H. Parry.[78]: 37

Exits

[edit]The entrances and exits are in two station houses, both on traffic islands between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue. The original station house is south of 72nd Street, while the newer one is in Verdi Square north of 72nd Street.[83] The preexisting median of Broadway made it possible for the IRT to provide an entrance to the station through a station house, with the platforms directly underneath.[79]

Southern station house

[edit]The original station house is one of a few surviving examples designed by Heins & LaFarge, which designed elements of many of the original IRT subway stations.[7][39] It is designed in the Flemish Renaissance style.[39] The station house was one of several on the original IRT; similar station houses were built at Atlantic Avenue, Bowling Green, Mott Avenue, 103rd Street, and 116th Street.[78]: 8 [12]: 46 [5]: 2 The station house occupies an area of 50 by 37 feet (15 by 11 m) and is aligned parallel to Broadway to create a focal point on Sherman Square. This places the station house slightly askew from the Manhattan street grid, of which 72nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue are part.[4]: 4 [78]: 12

The one-story station house contains exterior walls made of buff brick, with a water table made of granite blocks. A limestone string course runs atop the exterior wall. At the corners of the station house are limestone quoins, which support a copper-and-terracotta gable roof facing west and east. The ridge of the station house's roof is a skylight made of glass and metal.[84][4]: 4 [5]: 2–3 The doorways are centrally located on the north and south walls of the control house, topped by four terracotta finials and a rounded gable. There are terracotta crosses on each rounded gable with the number "72" embossed onto them. The south doorway contains four doors, above which is a pediment and an arched window made of glass and wrought iron. The north doorway is similar, but with five doors. Flanking the entrances are small windows.[4]: 4 [5]: 2–3 [78]: 12

Inside the station house are artful wrought iron pillars, dating back to the days of the original subway system, as well as decorated ceiling beams. The walls are made of white glass tiles. As originally configured, the station house had separate turnstile banks and token booths for each side, which were subsequently combined into a single fare-control area. The original station house has five staircases, two to the southbound platform and three to the northbound platform,[6]: 5–6 [5]: 3 [78]: 12 although it was originally built with two stairs to each platform.[22] On the north side, an unstaffed turnstile bank leads to 72nd Street; on the south side, three High Entry/Exit Turnstiles lead to 71st Street.[83] Above the exit doorways are decorative transoms and pediments with wayfinding signs.[6]: 6 [5]: 3 The interior of the original station house also had a restroom.[4]: 4

When the station was completed, the station house's architecture was unpopular; an editorial in The New York Times derided it as "A miserable monstrosity as to architecture".[85] The Times cited widespread complaints from neighborhood residents, including a member of the Colonial Club on Amsterdam Avenue and 72nd Street, who likened the structure's original dark-brown color to "a mud fence".[84] The West End Association had adopted a resolution in December 1904, declaring the station house "not only an offense to the eye, but a very serious danger to life and limb", and recommending that it be demolished.[5]: 3 [86]

Northern station house

[edit]The northern station house was designed by Richard Dattner & Partners and Gruzen Samton.[87] Its overall design was inspired by the Crystal Palace in London.[88] The northern station house contains the station's elevators and a crossover between the northbound and southbound platforms. This station house has two staircases and one elevator from each platform going up to street level where turnstile banks lead to 72nd and 73rd Streets.[83] Only the southern turnstile bank, which leads to 72nd Street, has a staffed token booth. The elevators from this station house make this station ADA-accessible.[69][83] There are also employee areas in the northern station house.[6]: 16

The northern station house has an artwork, Laced Canopy by Robert Hickman, which consists of a mosaic pattern on the central skylight, made up of over 100 mosaic panels. The knots within the pattern make up the notation for an excerpt of Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto.[82][89] The panels weigh over 161 pounds (73 kg) and stretch about 100 feet (30 m).[88]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The next local and express stations north, and the next local station south, are the same as on the present Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line. However, the next express station south was Grand Central.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ "Glossary". Second Avenue Subway Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement (SDEIS) (PDF). Vol. 1. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. March 4, 2003. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Our Subway Open: 150,000 Try It; Mayor McClellan Runs the First Official Train". The New York Times. October 28, 1904. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Annual Subway Ridership (2018–2023)". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "New York MPS Control House on 72nd Street". Records of the National Park Service, 1785 – 2006, Series: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013 – 2017, Box: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: New York, ID: 75313849. National Archives.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Interborough Rapid Transit System, 72nd Street Control House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 9, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "New York MPS 72nd Street Subway Station (IRT)". Records of the National Park Service, 1785 – 2006, Series: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013 – 2017, Box: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: New York, ID: 75313923. National Archives.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Interborough Rapid Transit System, Underground Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 23, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walker, James Blaine (1918). Fifty Years of Rapid Transit — 1864 to 1917. New York, N.Y.: Law Printing. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Report of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners for the City of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1904 Accompanied By Reports of the Chief Engineer and of the Auditor. Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. 1905. pp. 229–236.

- ^ "First of Subway Tests; West Side Experimental Trains to be Run by Jan. 1 Broadway Tunnel Tracks Laid, Except on Three Little Sections, to 104th Street – Power House Delays". The New York Times. November 14, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ "Clamor for Tickets for Subway Opening; Distribution Plan Criticised by Engineers and Many Others". The New York Times. October 26, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 25, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0511-5. OCLC 9829395.

- ^ "Our First Subway Completed At Last — Opening of the Van Cortlandt Extension Finishes System Begun in 1900 — The Job Cost $60,000,000 — A Twenty-Mile Ride from Brooklyn to 242d Street for a Nickel Is Possible Now". The New York Times. August 2, 1908. p. 10. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ The Merchants' Association of New York Pocket Guide to New York. Merchants' Association of New York. March 1906. pp. 19–26.

- ^ Herries, William (1916). Brooklyn Daily Eagle Almanac. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 119. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ "Exercises in City Hall; Mayor Declares Subway Open – Ovations for Parsons and McDonald". The New York Times. October 28, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hood, Clifton (1978). "The Impact of the IRT in New York City" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 146–207 (PDF pp. 147–208). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Report of the Public Service Commission for the First District of the State of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1910. Public Service Commission. 1911. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Mehren, Edward J.; Meyer, Henry Coddington; Goodell, John M. (1911). Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer. McGraw Publishing Company. pp. 520–522. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Ten-car Trains in Subway to-day; New Service Begins on Lenox Av. Line and Will Be Extended to Broadway To-morrow". The New York Times. January 23, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ "Open New Subway Lines to Traffic; Called a Triumph" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1918. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ a b New York (State). Transit Commission (1924). Proceedings of the Transit Commission, State of New York. pp. 593–594. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ Proceedings of the Board of Transportation of the City of New York. New York City Board of Transportation. 1930. p. 303. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Legislature, New York (State) (1937). Legislative Document. J.B. Lyon Company. p. 15. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ Proceedings of the New York City Board of Transportation. New York City Board of Transportation. 1945. p. 423. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "City Transit Unity Is Now a Reality; Title to I.R.T. Lines Passes to Municipality, Ending 19-Year Campaign". The New York Times. June 13, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ "Transit Unification Completed As City Takes Over I. R. T. Lines: Systems Come Under Single Control After Efforts Begun in 1921; Mayor Is Jubilant at City Hall Ceremony Recalling 1904 Celebration". New York Herald Tribune. June 13, 1940. p. 25. ProQuest 1248134780.

- ^ Brown, Nicole (May 17, 2019). "How did the MTA subway lines get their letter or number? NYCurious". amNewYork. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Friedlander, Alex; Lonto, Arthur; Raudenbush, Henry (April 1960). "A Summary of Services on the IRT Division, NYCTA" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. 3 (1). Electric Railroaders' Association: 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Report. New York City Transit Authority. 1953. p. 32. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Minutes and Proceedings. New York City Transit Authority. 1955. pp. 3, 254, 1457. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Proceedings of the New York City Transit Authority Relating to Matters Other Than Operation. New York City Transit Authority. 1961. pp. 73, 179. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c "High-Speed Broadway Local Service Began in 1959". The Bulletin. 52 (2). New York Division, Electric Railroaders' Association. February 2009. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016 – via Issuu.

- ^ "Wagner Praises Modernized IRT — Mayor and Transit Authority Are Hailed as West Side Changes Take Effect". The New York Times. February 7, 1959. p. 21. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ Aciman, Andre (January 8, 1999). "My Manhattan — Next Stop: Subway's Past". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ Annual Report For The Year Ending June 30, 1959 (PDF). New York City Transit Authority. 1959. pp. 8–10. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ Comptroller, New York (N Y. ) Office of the (1973). Report of the Comptroller. p. 218. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Subway Station Scored as Unsafe". The New York Times. March 6, 1976. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Fowler, Glenn (January 10, 1979). "Its Status Is More Than Token: Subway Kiosk Now Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (August 29, 1982). "Architecture View; is the Lincoln West Project Right for the City?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Moritz, Owen (September 19, 1982). "1B Lincoln West: a real blockbuster". New York Daily News. p. 20. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Anderson, Susan Heller; Dunlap, David W. (December 19, 1984). "New York Day by Day; A Hint of Trump's Vision Of the West Side's Future". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. June 20, 1988. p. 8. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "Ben & Jerry mixing it up to sweeten subway station". The Brattleboro Reformer. April 5, 1988. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "Dukakis upstaged by Hart in Vt". The Burlington Free Press. December 20, 1987. p. 19. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Delegates say questions from media a little silly". The Burlington Free Press. July 10, 1988. p. 39. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "We're Improving the 72 Street Station". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. 1989. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Foran, Katherine (September 1, 1989). "More Routes Open For Holiday Traffic". Newsday. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Denny (February 18, 2001). "Neighborhood Report: Upper West Side; Facing a Detour, Riders Want a Shorter, Free One". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Randy (April 10, 2001). "Tunnel Vision; 72nd St. Station Project Has Riders Feeling Squeezed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (July 22, 1992). "Debate on Trump's West Side Proposal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Fee, Walter (May 18, 1992). "Trump Banks On City, State Boost". Newsday. p. 25. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 278506690. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ Bressi, Todd W. (October 20, 1992). "How Private Projects Cost the Public". Newsday. pp. 67, 109. ISSN 2574-5298. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ Moritz, Owen (October 27, 1992). "1M sweetener from Donald". New York Daily News. p. 4. ISSN 2692-1251. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b McKinley, James C. Jr. (October 15, 1994). "City to Delay Subway Work At 6 Stations". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (May 22, 1994). "Federal Money Sought for Repair of 72d Street Subway Station". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Allon, Janet (January 21, 1996). "Neighborhood Report: Upper West Side; Test for Non-Genteel Group: Fight Over 72d Street Station". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Duggan, Dennis (February 15, 1996). "Station Has Makings of 'Headhouse'". Newsday. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Architects, Richard Dattner & Partners (2008). Dattner Architects. Images Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-86470-285-9. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Wong, Edward (June 7, 2000). "72nd St. Station Renovation Should Do More, Critics Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Rutenberg, James (July 17, 1998). "W. Siders call MTA plans shortsighted for IRT's 72nd St". New York Daily News. p. 28. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Lueck, Thomas J. (May 28, 1998). "2d Subway Entry Planned At 72d St. and Broadway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Day, Sherri (June 18, 2000). "Neighborhood Report: Upper West Side; Are Renovations in Subway a Threat to the Life Upstairs?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ February 1999 MTA Board Meeting. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. February 22, 1999. pp. 63–64. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ "What's happening? 1 2 3 9 72nd Street station Rehabilitation and expansion begins March 2000, ends Summer 2003". Flickr. New York City Transit. 2000. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Denny (February 4, 2001). "Neighborhood Report: Upper West Side; A Messy Construction Project Grows Even More Tangled". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Fordham environmental law journal. 2001. p. 284. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (May 19, 2002). "Streetscapes/Subway Platforms; Letting the Sun Shine In (Published 2002)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 30, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ a b "New Headhouse Opens at West 72nd Street". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 29, 2002. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ Transit Committee Meeting. MTA New York City Transit Committee. February 2005. p. 92. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "12 IRT Subway Stops Get Landmark Status". The New York Times. October 27, 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Dougherty, Peter (2006) [2002]. Tracks of the New York City Subway 2006 (3rd ed.). Dougherty. OCLC 49777633 – via Google Books.

- ^ "1 Subway Timetable, Effective December 17, 2023". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ a b "2 Subway Timetable, Effective June 26, 2022". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "3 Subway Timetable, Effective June 30, 2024". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "MTA Accessible Stations". MTA. May 20, 2022. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Framberger, David J. (1978). "Architectural Designs for New York's First Subway" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 1–46 (PDF pp. 367–412). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c Institution of Civil Engineers (Great Britain) (1908). Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. The Institution. p. 106. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Term First Department. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Scott, Charles (1978). "Design and Construction of the IRT: Civil Engineering" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 208–282 (PDF pp. 209–283). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Smith, Roberta (January 2, 2004). "Critic's Notebook; The Rush-Hour Revelations Of an Underground Museum". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Upper West Side" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "Sherman Square Subway Entrance; An "Architectural Freak" That Has Spoiled a View and Aroused the Ire of Residents in one of the City's Finest Neighborhoods". The New York Times. September 11, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (October 10, 2004). "New York's Subway: That Engineering Marvel Also Had Architects". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Proceedings of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners (PDF). Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. January 24, 1905. p. 576 (PDF p. 4). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (May 19, 2002). "Streetscapes/Subway Platforms; Letting the Sun Shine In". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 30, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Randy (May 14, 2002). "Tunnel Vision; Hunting for a Thief With Underground Connections". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "Laced Canopy, 2002". MTA Arts & Design. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

External links

[edit]- nycsubway.org – IRT West Side Line: 72nd Street

- Forgotten NY – Original 28 – NYC's First 28 Subway Stations

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch