Ariane 6

| |

| Function | A62: Medium-lift launch vehicle A64: Heavy-lift launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | ArianeGroup |

| Country of origin | European multi-national[a] |

| Project cost | €3.6 billion[1] |

| Cost per launch | A62: €75 million A64: €115 million[2][3] |

| Size | |

| Height | 63 m (207 ft) |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Mass | A62: 530,000 kg (1,170,000 lb) A64: 860,000 kg (1,900,000 lb) |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | |

| Mass | A64: 21,650 kg (47,730 lb) A62: 10,350 kg (22,820 lb)[4] |

| Payload to GTO | |

| Orbital inclination | 6° |

| Mass | A64: 11,500 kg (25,400 lb) A62: 4,500 kg (9,900 lb)[4] |

| Payload to GEO | |

| Orbital inclination | 0° |

| Mass | A64: 5,000 kg (11,000 lb)[4] |

| Payload to SSO | |

| Orbital inclination | 97.4° |

| Mass | A64: 15,500 kg (34,200 lb) A62: 7,200 kg (15,900 lb)[4] |

| Payload to LTO | |

| Mass | A64: 8,600 kg (19,000 lb) A62: 3,500 kg (7,700 lb)[4] |

| Associated rockets | |

| Family | Ariane |

| Comparable | Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy, H3, Vulcan Centaur |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Active |

| Launch sites | Guiana Space Centre, ELA-4 |

| Total launches | 1 |

| Partial failure(s) | 1[disputed – discuss] |

| First flight | 9 July 2024[5] |

| Boosters – P120C | |

| No. boosters | 2 or 4 |

| Diameter | 3 m (9.8 ft) |

| Propellant mass | 142,000 kg (313,000 lb) |

| Maximum thrust | 3,500 kN (790,000 lbf) each |

| Burn time | 130 seconds |

| Propellant | HTPB / AP / Al |

| First stage | |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Propellant mass | 140,000 kg (310,000 lb) |

| Powered by | 1 × Vulcain 2.1 |

| Maximum thrust | 1,370 kN (310,000 lbf) |

| Burn time | 468 seconds |

| Propellant | LH2 / LOX |

| Second stage | |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Propellant mass | 31,000 kg (68,000 lb) |

| Powered by | 1 × Vinci |

| Maximum thrust | 180 kN (40,000 lbf) |

| Burn time | Up to 900 seconds and four burns[6] |

| Propellant | LH2 / LOX |

Ariane 6 is a European expendable launch system operated by Arianespace and developed and produced by ArianeGroup on behalf of the European Space Agency (ESA). It replaces Ariane 5, as part of the Ariane launch vehicle family.

This two-stage rocket utilizes liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen (hydrolox) engines. The first stage features an upgraded Vulcain engine from Ariane 5, while the second uses the Vinci engine, designed specifically for this rocket. The Ariane 62 variant uses two P120 solid rocket boosters, while Ariane 64 uses four. The P120 booster is shared with Europe's other launch vehicle, Vega C, and is an improved version of the P80 rocket stage used on the original Vega.

Selected in December 2014 over an all-solid-fuel option, Ariane 6 was originally targeted for a 2020 launch. However, the program encountered delays, with the first launch occurring on 9 July 2024.

Ariane 6 is designed to halve launch costs and increase annual capacity from seven to eleven missions compared to its predecessor, but the program has faced controversy over high costs and lack of reusability versus competitors' rockets, such as SpaceX's Falcon 9. European officials defend the program, saying it provides crucial independent space access for its member states.

Description[edit]

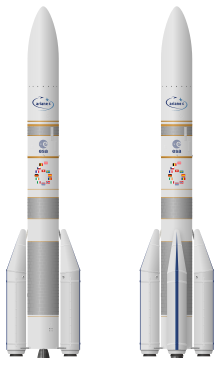

Two variants of Ariane 6 are being developed:

- Ariane 62 (A62), with two P120 solid boosters, weighs around 530,000 kg (1,170,000 lb) at liftoff and is mainly for government and scientific missions.[7] It can launch up to 4,500 kg (9,900 lb) into geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO) and 10,350 kg (22,820 lb) into low Earth orbit (LEO). The first launch used this variant.

- Ariane 64 (A64), with four P120 boosters, has a liftoff weight of around 860,000 kg (1,900,000 lb)[8] and is intended for commercial dual-satellite launches[7] of up to 11,500 kg (25,400 lb) into GTO and 21,500 kg (47,400 lb) into LEO. Like Ariane 5, it will be able to launch two geosynchronous satellites together. The first launch is planned for no earlier than 2025

First stage[edit]

The first (lower) stage of Ariane 6 is called the Lower Liquid Propulsion Module (LLPM). It is powered by a single Vulcain 2.1 engine, burning liquid hydrogen (LH2) with liquid oxygen (LOX).[9] Vulcain 2.1 is an updated version of the Vulcain 2 engine from Ariane 5 with lower manufacturing costs.[clarification needed] The LLPM is 5.4 m (18 ft) in diameter and contains approximately 140 tonnes (310,000 lb) of propellant.[10]

Boosters[edit]

Additional thrust for the first stage will be provided by either two or four P120 model solid rocket boosters, known within Ariane 6 nomenclature as Equipped Solid Rockets (ESR).[9] Each booster contains approximately 142,000 kilograms (313,000 lb) of propellant and delivers up to 4,650 kN (1,050,000 lbf) of thrust. The P120 motor is also used in the first stage of the upgraded Vega C launcher. By sharing motors, production volumes can be increased, lowering production costs.[11] The first full-scale test of the ESR occurred at Kourou, French Guiana, on 16 July 2018, and the test completed successfully with thrust reaching 4,615 kN (1,037,000 lbf) in vacuum.[12][13][14]

Second stage[edit]

The second (upper) stage of Ariane 6 is called the Upper Liquid Propulsion Module (ULPM). It shares the same 5.4 m (18 ft) diameter as the LLPM, and also burns liquid hydrogen with oxygen. It is powered by the Vinci engine, which delivers 180 kN (40,000 lbf) of thrust and is capable of multiple restarts.[9] The ULPM will carry about 31 tonnes (68,000 lb) of propellant.[11]

History[edit]

Ariane 6 was conceived in the early 2010s to be a replacement launch vehicle for Ariane 5, and a number of concepts and high-level designs were suggested and proposed during 2012–2015. Development funding from several European governments was secured by early 2016, and contracts were signed to begin detailed design and the build of test articles. In 2019, the maiden orbital flight had been planned for 2020,[15] however by May 2020, the planned initial launch date was delayed into 2021.[16] In October 2020, the European Space Agency (ESA) formally requested an additional €230 million in funding from the countries sponsoring the project to complete development of the rocket and get the vehicle to its first test flight, which had slipped to the second quarter of 2022.[17] By June 2021, the date had delayed to late 2022.[18] In June 2022, a delay was announced to "some time in 2023"[19] and by October 2022, ESA clarified that the first launch would be no earlier than the fourth quarter of 2023, while providing no public reason for the delay.[20] In August 2023, ESA announced that the date for the first launch had slipped again to 2024.[21]

Concept and early development: 2010–2015[edit]

Following detailed definition studies in 2012,[22] ESA announced in July 2013 the selection of the "PPH" (first stage of three P145 rocket motors, second stage of one P145 rocket motor, and H32 cryogenic upper stage) configuration for Ariane 6.[23] It would be capable of launching up to 6,500 kg (14,300 lb) to Geostationary transfer orbit (GTO),[24] with a first flight projected to be as early as 2021–2022.[25] Development was projected to cost €4 billion as of May 2013[update].[26] A 2014 study concluded that development cost could be reduced to about €3 billion by limiting contractors to five countries.[27]

While Ariane 5 typically launches one large and one medium satellite at a time, the PPH proposal for Ariane 6 was intended for single payloads, with an early 2014 price estimate of approximately US$95 million per launch.[28] The SpaceX Falcon 9 and the Chinese Long March 3B both launch smaller payloads but at lower prices, approximately $57 million and $72 million respectively as of early 2014, making the Falcon 9 launch of a midsize satellite competitive with the cost of the lower slot of a dual payload Ariane 5.[28] For lightweight all-electric satellites, Arianespace intended to use the restartable Vinci engine to deliver the satellites closer to their operational orbit than the Falcon 9 could, thus reducing the time required to transfer to geostationary orbit by several months.[28]

Ariane 6.1 and Ariane 6.2 proposals[edit]

In June 2014, Airbus and Safran surprised ESA by announcing a counter proposal for the Ariane 6 project: a 50/50 joint venture to develop the rocket, which would also involve buying out the French government's CNES interest in Arianespace.[29][30]

This proposed launch system would come in two variants, Ariane 6.1 and Ariane 6.2.[31] While both would use a cryogenic main stage powered by a Vulcain 2 engine and two P145 solid boosters, Ariane 6.1 would feature a cryogenic upper stage powered by the Vinci engine and boost up to 8,500 kg (18,700 lb) to GTO, while Ariane 6.2 would use a lower-cost hypergolic upper stage powered by the Aestus engine. Ariane 6.1 would have the ability to launch two electrically powered satellites at once, while Ariane 6.2 would be focused on launching government payloads.

French newspaper La Tribune questioned whether Airbus Defence and Space could deliver on the promised costs for their Ariane 6 proposal, and whether Airbus and Safran Group could be trusted when they were found to be responsible for a failure of Ariane 5 flight 517 in 2002 and a more recent 2013 failure of the M51 ballistic missile.[32] The companies were also criticised for being unwilling to incur development risks, and asking for higher initial funding than originally planned – €2.6 billion instead of €2.3 billion. Estimated launch prices of €85 million for Ariane 6.1 and €69 million for Ariane 6.2 did not compare favorably to SpaceX offerings.[33] During the meeting of EU ministers in Geneva on 7 June 2014, these prices were deemed too high and no agreement with manufacturers was reached.[34]

Ariane 62 and Ariane 64 proposals[edit]

Following criticism of the Ariane 6 PPH design, France unveiled a revised Ariane 6 proposal in September 2014.[35] This launcher would use a cryogenic main stage powered by the Vulcain 2 and upper stage powered by the Vinci, but vary the number of solid boosters. With two P120 boosters, Ariane 6 would launch up to 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) to GTO at a cost of €75 million. With four boosters, Ariane 6 would be able to launch two satellites totaling 11,000 kg (24,000 lb) to GTO at a cost of €90 million.[36]

This proposal, unlike Ariane 6 PPH, offered a scalable launcher while retaining Ariane 5's dual-launch capability. The proposal also included simplification of the industrial and institutional organisation along with a better and cheaper version of the Vulcain 2 engine for the main stage.[35][36] Although Ariane 6 was projected to have "lower estimated recurring production costs", it was projected to have "a higher overall development cost owing to the need for a new, Ariane 6-dedicated, launch pad".[37]

The Italian, French, and German space ministers met on 23 September 2014, in order to plan strategy and assess the possibility for agreement on funding for the Ariane 5 successor,[38] and in December 2014, ESA selected the Ariane 62 and Ariane 64 designs for development and funding.[39]

At the 2022 International Astronautical Congress, ArianeGroup announced the proposed "Smart Upper Stage for Innovative Exploration", a reusable upper stage for the 64 (or later) variant, capable of autonomous cargo operations or carrying five astronauts to LEO.[40]

Test vehicle development: 2016–2021[edit]

In November 2015, an updated design of Ariane 64 and 62 was presented, with new nose cones on the boosters, main stage diameter increased to 5.4 m (18 ft), and the height decreased to 60 m (200 ft).[41]

The basic design for Ariane 6 was finalised in January 2016 as an expendable liquid-fuelled core stage plus expendable solid-rocket-boosters design. Development advanced into detailed design and production phases, with the first major contracts already signed.[42][43] Unlike previous Ariane rockets, which are assembled and fueled vertically before being transported to the launchpad, the Ariane 6 main stages were to be assembled horizontally at the new integration hall in Les Mureaux and then transported to French Guiana, to be erected and integrated with boosters and payload.[44]

The horizontal assembly process was inspired by the Russian tradition for Soyuz and Proton launchers – which had more recently been applied to the American Delta IV and Falcon 9 boosters[45] – with a stated goal of halving production costs.[46]

The industrial production process was completely overhauled, allowing synchronized workflow between several European production sites moving at a monthly cadence, which would enable twelve launches per year, doubling Ariane 5's yearly capacity.[44] To further lower the price, Ariane 6 engines were to use 3D printed components.[47] Ariane 6 was to be the first large rocket to use a laser ignition system developed by Austria's Carinthian Research Center (CTR), that was previously deployed in automotive and turbine engines.[48] A solid state laser offers an advantage over electrical ignition systems in that it is more flexible with regards to the location of the plasma within the combustion chamber, offers a much higher pulse power and can tolerate a wider range of fuel-air mixture ratios.[49]

Reorganisation of the industry behind a new launch vehicle, leading to the creation of Airbus Safran Launchers (ASL), also started a review by the French government into tax matters, and the European Commission over a possible conflict of interest if Airbus Defence and Space, a satellite manufacturer, were to purchase launches from ASL.[47]

While development was initially slated to be substantially complete in 2019, with an initial launch in 2020, the initial launch date has slipped several times: first to 2021,[50] then to 2022,[17][18] then to 2023,[19] and then to 2024.[51] In October 2022, Arianespace expected the maiden flight to occur in 2023,[20] although in December 2023, Arianespace once again set the flight to occur on 15 June 2024.[51] In June 2024, ESA Executive said its first launch was postponed to July 9th 2024.[52] The maiden flight took place 9 July 2024 and successfully orbited some satellites even though the mission did suffer some problems.

Other development options[edit]

CNES began studies in 2010[53] on an alternative, reusable first stage for Ariane 6, using a mix of liquid oxygen and liquid methane rather than liquid hydrogen that is used in the 2016 Ariane 6 first-stage design. The methane-powered core could use one or more engines, matching capabilities of Ariane 64 with only two boosters instead of four. As of January 2015[update], the economic feasibility of reusing an entire stage remained in question. Concurrent with the liquid fly-back booster research in the late 1990s and early 2000s, CNES along with Russia concluded studies[when?] indicating that reusing the first stage was economically unviable as manufacturing ten rockets a year was cheaper and more feasible than recovery, refurbishment and loss of performance caused by reusability.[54] It was suggested[by whom?] that with a Arianespace launch schedule of 12 flights per year, an engine that could be reused a dozen times would produce a demand for only one engine per year, making supporting an ongoing engine manufacturing supply chain unviable.[citation needed]

In June 2015, Airbus Defence and Space announced that Adeline, a partially reusable first stage, would become operational between 2025 and 2030, and that it would be developed as a subsequent first stage for Ariane 6. Rather than developing a way to reuse an entire first stage (like SpaceX), Airbus proposed a system where only high-value parts would be safely returned using a winged module at the bottom of the rocket stack.[53]

In August 2016, ASL gave some more details about future development plans building on the Ariane 6 design. CEO Alain Charmeau revealed that Airbus Safran were now working along two main lines: first, continuing work (at the company's own expense) on the recoverable Adeline engine-and-avionics module; and second, beginning development of a next-generation engine to be called Prometheus. This engine would have about the same thrust as the Vulcain 2 currently powering Ariane 5, but would burn methane instead of liquid hydrogen. Charmeau was non-committal about whether Prometheus (still only in the first few months of development) could be used as an expendable replacement for the Vulcain 2 in Ariane 6, or whether it was tied to the re-usable Adeline design, saying only that "We are cautious, and we prefer to speak when are sure of what we announce... But certainly this engine could very well fit with the first stage of Ariane 6 one day", a decision on whether to proceed with Prometheus in an expendable or reusable role could be made between 2025 and 2030.[55]

In 2017, the Prometheus engine project was revealed to have the aim of reducing the engine unit cost from the €10 million of the Vulcain2 to €1 million and allowing the engine to be reused up to five times.[56] The engine development is said to be part of a broader effort – codename Ariane NEXT[57] – to reduce Ariane launch costs by a factor of two beyond improvements brought by Ariane 6. The Ariane NEXT initiative includes a reusable sounding rocket, Callisto, to test the performance of various fuels in new engine designs.[58]

Production[edit]

In a January 2019 interview, Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël said that the company would require four more institutional launches for Ariane 6 to sign a manufacturing contract. Launch contracts would be needed for the transitional period of 2020–2023 when Ariane 5 will be phased out and gradually replaced by Ariane 6. The company would require European institutions to become an anchor customer for the launcher. In response, ESA representatives said the agency was working on shifting the 2022 launch of the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer from Ariane 5 ECA to Ariane 64, further indicating that there are other institutional customers in Europe that must put their weight behind the project, such as the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT) or the European Commission.

As of January 2019[update], Arianespace had sold three flights of the Ariane 6 launch vehicle.[59] One month later, they added a satellite internet constellation launch contract with OneWeb to utilize the maiden launch of Ariane 6 to help populate the large 600-satellite constellation.[60]

On 6 May 2019, Arianespace ordered the first production batch of 14 Ariane 6 rockets, for missions to be conducted between 2021 and 2023.[61]

Rocket components are transported by sea from Europe to the Guiana Space Centre aboard the Canopée, a cargo vessel that uses sails to assist with its propulsion, reducing fuel use.[62][63]

Development funding[edit]

Ariane 6 is being developed in a public-private partnership with the majority of the funding coming from various ESA government sources — €2.815 billion — while €400 million is reported to be "industry's share".[64]

The ESA Council approved the project on 3 November 2016,[65] and the ESA Industrial Policy Committee released the required funds on 8 November 2016.[66]

In January 2020, two EU institutions, the European Investment Bank and the European Commission, loaned €100 million to Arianespace, drawing from the Horizon 2020 and Investment Plan for Europe corporate investment programmes. The 10-year loan's repayment is tied to the financial success of the Ariane 6 project.[67]

Launch history[edit]

List of launches[edit]

| Flight No. | Date Time (UTC) | Rocket type Serial No. | Launch site | Payload | Payload mass | Orbit | Customers | Launch outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA262 | 9 July 2024 19:00 | Ariane 6 62 601 | Guiana ELA-4 | Multiple rideshare payloads | 1,600 kg[68] | LEO | Various | Partial failure |

| Maiden flight of Ariane 6. It was a test flight carrying a 1.6 ton mass simulator plus a number of small cubesats and other experiments as rideshare payloads. The launch was delayed by an hour due to an issue with a data acquisition system, but after that the countdown proceed without issue, and the rocket successfully lifted off at 19:00 UTC, flying a northeastern trajectory that took it over Europe. The solid rocket boosters and the rocket's core stage performed nominally during the flight. The Vinci engine on the upper stage was first started at T+8 minutes, firing for 10 minutes to place the rocket in a preliminary orbit. After a coast phase, the upper stage was successfully reignited at T+56 minutes, firing for 22 seconds to circularize its orbit. At this point in the mission, the cubesats were deployed as scheduled. At T+1 hour and 14 minutes, the rocket's auxiliary propulsion system (APU)—which is used for upper stage tank pressurization and also for minor orbital adjustments—failed shortly after being reignited for the final phase of the mission. Since the APU is needed for relighting the upper stage's Vinci engine, this malfunction precluded the third and final planned burn of the upper stage, which was planned for T+2 hours and 37 minutes and would deorbit the vehicle safely over the Pacific Ocean. This left the upper stage, along with two reentry capsule payloads that could not be deployed, stranded in their 580-km circular orbit. At this altitude, their natural orbital decay due to atmospheric drag is expected to take decades.[69][70][71][72] The payload was primarily a mass simulator but carried multiple rideshare payloads. They include five experiments (PariSat by GAREF, Peregrinus by Sint-Pieterscollege, LIFI by OLEDCOMM, SIDLOC by Libre Space and YPSat by ESA) and eight CubeSats (OOV-Cube by RapidCube, Curium One by PTS, ISTSat by University of Lisbon, 3Cat-4 by Polytechnic University of Catalonia, GRBBEta by Spacemanic, ROBUSTA-3 by University of Montpellier, CURIE by NASA and Replicator by Orbital Matter), which were deployed correctly. The launch also carried two reentry capsules (SpaceCase SC-X01 by ArianeGroup and Nyx Bikini by The Exploration Company) that were slated to be deployed after the second stage was to be deorbited, but the vehicle did not make reentry as planned.[73][74] | ||||||||

Planned launches[edit]

| Date Time (UTC) | Type | Payload | Orbit | Customers | Launch status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q4 2024[71][70] | Ariane 62 | CSO-3 | SSO | CNES / DGA | Planned | ||

| French military spy satellite. Despite the problem with the APU on Ariane 6's first flight, an Arianespace official said they are still "perfectly on track now to make the second launch this year".[71] | |||||||

| 2025[75][76] | Ariane 62 | Galileo FOC FM 29, 30 | MEO | ESA | Planned | ||

| 2025[75][76] | Ariane 62 | Galileo FOC FM 31, 32 | MEO | ESA | Planned | ||

| 2025[76] | Ariane 62 | Galileo FOC FM 33, 34 | MEO | ESA | Planned | ||

| 2025[77] | Ariane 64 | Intelsat-41, 44 | GTO | Intelsat | Planned | ||

| 2025[75][78] | Ariane 64 | Optus-11 | GTO | Optus | Planned | ||

| 2025[75][79][80] | Ariane 64 | Uhura-1 (Node-1)[81] | GTO | Skyloom | Planned | ||

| 2025[82] | Ariane 6 | Galileo G2 1 | MEO | ESA | Planned | ||

| 2025[83] | Ariane 6 | Hellas Sat 5 | GTO | Hellas Sat | Planned | ||

| Q2 2026[84] | Ariane 64[85] | MTG-I2[86] | GTO | EUMETSAT | Planned | ||

| H1 2026[87] | Ariane 64 | Intelsat 45 | GTO | Intelsat | Planned | ||

| Q4 2026[88] | Ariane 64 | Multi-Launch Service (MLS) #1 rideshare mission | GTO | TBA | Planned | ||

| 2026[89] | Ariane 62[90] | PLATO | Sun–Earth L2 | ESA | Planned | ||

| Q4 2027[88] | Ariane 64 | MLS #2 rideshare mission | GTO | TBA | Planned | ||

| 2027[91] | Ariane 64 | Earth Return Orbiter | Areocentric | ESA | Planned | ||

| Q4 2028[88] | Ariane 64 | MLS #3 rideshare mission | GTO | TBA | Planned | ||

| Q3 2029[88] | Ariane 64 | MLS #4 rideshare mission | GTO | TBA | Planned | ||

| 2029[92] | Ariane 62 | ARIEL, Comet Interceptor | Sun–Earth L2 | ESA | Planned | ||

| 2030[93][94] | Ariane 64 | Argonaut (lunar lander) | TLI | ESA | Planned | ||

| 2035[95] | Ariane 64[96] | Athena | Sun–Earth L2, Halo orbit | ESA | Planned | ||

| 2035[97] | Ariane 6 | LISA | Heliocentric | ESA | Planned | ||

| TBD[98] | Ariane 64 | 18 launches of Project Kuiper (35–40 satellites)[99] | LEO | Kuiper Systems | Planned | ||

| TBD[100] | Ariane 62 | Electra | GTO | SES S.A. / ESA | Planned | ||

| TBD[100] | Ariane 62 | Eutelsat ×5 | GTO | Eutelsat | Planned | ||

Criticism[edit]

Ariane 6 has been subject to criticism for its cost per launch and lack of reusability.

When initially approved by ESA in 2012, the rocket was envisioned as a modernized version of Ariane 5, optimized for cost. At the time, commercial competitors like SpaceX were already putting downward pressure on launch costs[101][102]. However, these companies had made few successful flights and had not yet proven that reusability would be economically beneficial. The Space Shuttle was cited by some as an example to the contrary. In the more than a decade that Ariane 6 was in development, the project was delayed and went over budget. During that same time, SpaceX continued to iteratively develop its Falcon 9 rocket, nearly doubling its payload capacity and successfully landing rockets for reuse, making it more capable and far less costly than Ariane 6.[103][104]

European officials have defended Ariane 6 stating that its governments need access to space, independent from other states or private companies. They point to geopolitical events that cut off Europe's access to Russian Soyuz rockets in as an example of that need. They also defend the rocket's lack of reusability, arguing that it would not be economically viable given the rocket’s fewer planned launches.[105][106]

The ESA's member states agreed to subsidize the rocket with up to €340 million annually from its 16th to its 42nd flight (expected in 2031) in return for an 11% discount on launches.[105][107]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Media backgrounder for ESA Council at Ministerial Level" (Press release). ESA. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Rich, Smith (2 June 2018). "Europe Complains: SpaceX Rocket Prices Are Too Cheap to Beat". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Gallois, Dominique (1 December 2014). "Ariane 6, un chantier européen pour rester dans la course spatiale" [Ariane 6, a European site to remain in the space race]. Le Monde.fr (in French). Le Monde. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Lagier, Roland (March 2021). "Ariane 6 User's Manual Issue 2 Revision 0" (PDF). Arianespace. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Mathewson, Samantha (8 June 2024). "At long last: Europe's new Ariane 6 rocket set to debut on July 9". Space.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "Ariane 6 Vinci engine: successful qualification tests". ArianeGroup (Press release). 22 October 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b Amos, Jonathan (3 December 2014). "Europe to press ahead with Ariane 6 rocket". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ "Ariane 6 - Ariane Group". ArianeGroup. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ a b c "Who we are" (PDF). Arianespace. May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Ariane 6". ESA. 23 January 2017. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Ariane 6". CNES. 2 December 2014. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Largest-ever solid rocket motor poised for first hot firing". SpaceDaily. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Successful first test firing for the P120C solid rocket motor for Ariane 6 and Vega C". Ariane Group. 16 July 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (16 July 2018). "Static Fire test for Europe's P120C rocket motor". NASASpaceFlight. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "Ariane 6 series production begins with first batch of 14 launchers". Arianespace. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ "Ariane 6 maiden flight likely slipping to 2021". SpaceNews. 20 May 2020. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ a b Parsonson, Andrew (29 October 2020). "ESA request 230 million more for Ariane 6 as maiden flight slips to 2022". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b Berger, Eric (21 June 2021). "The Ariane 6 debut is slipping again as Europe hopes for a late 2022 launch". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b Rainbow, Jason (13 June 2022). "Ariane 6 launch debut pushed into 2023". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (19 October 2022). "Ariane 6 first launch slips to late 2023". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 25 September 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (9 August 2023). "ESA confirms Ariane 6 debut to slip to 2024". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Stephen Clark (21 November 2012). "European ministers decide to stick with Ariane 5, for now". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Dumont, Etienne; Božić, Ognjan; May, Stefan; Mierheim, Olaf; Chrupalla, David; Beyland, Lutz; Karl, Sebastian; Klevanski, Josef; Johannsson, Magni; Clark, Vanessa; Stief, Malte; Keiderling, David; Koch, Patrick; Acquatella, B. Paul; Saile, Dominik; Poppe, Georg; Traudt, Tobias; Manfletti, Chiara (February 2015). "Ariane 6 PPH Architecture Critical Analysis: Second Iteration Loop" – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Feldman, Mia (11 July 2013). "European Space Agency Reveals New Rocket Design". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (22 June 2017). "Full thrust on Europe's new rocket". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (24 May 2013). "With Ariane 6 Launch Site Selected, CNES Aims To Freeze Design of the New Rocket in July". Space News. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

Ariane 6 would fly in 2020 assuming a development go-ahead in 2014. CNES's Ariane 6 team is operating under the "triple-seven" mantra, meaning seven years' development, 7 metric tons of satellite payload to geostationary transfer orbit and 70 million euros in launch costs. CNES estimates that Ariane 6 would cost 4 billion euros to develop, including ESA's customary program management fees and a 20% margin that ESA embeds in most of its programs.

- ^ Peter B. De Selding (18 March 2014). "Questions Swirl around Future of Europe's Ariane Launcher Program". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Svitak, Amy (10 March 2014). "SpaceX Says Falcon 9 To Compete For EELV This Year". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

As SpaceX and other launch contenders enter the sector – including new rockets in India, China and Russia – Europe is also investing in a midlife upgrade of Ariane 5, the Ariane 5 ME (Midterm Evolution), which aims to boost performance 20% with no corresponding increase in cost. At the same time, Europe is considering funding a smaller, less capable but more affordable successor to the heavy-lift launcher, Ariane 6, which would send up to 6,500 kg (14,300 lb) to GTO for around US$95 million per launch.

- ^ de Selding, Peter (20 June 2014). "Airbus and Safran Propose New Ariane 6 Design, Reorganisation of Europe's Rocket Industry". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

European space-hardware builders Airbus and Safran have proposed that the French and European space agencies scrap much of their previous 18 months' work on a next-generation Ariane 6 rocket in favour of a design that includes much more liquid propulsion.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (5 July 2014). "Ariane 6: Customers call the shots". BBC. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ "Safran-Airbus Group launcher activities agreement". Safran Group. 16 June 2014. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Michel Cabirol (7 July 2014). "Faut-il donner toutes les clés d'Ariane 6 à Airbus et Safran?" (in French). La Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Cabirol, Michel (7 July 2014). "Privatisation d'Ariane 6 : comment Airbus et Safran négocient le "casse du siècle"" [Ariane 6 privatized: how Airbus and Safran negotiate the "heist of the century"] (in French). La Tribune. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Cyrille Vanlerberghe (8 July 2014). "Le choix d'Ariane 6 divise industriels et agences spatiales" (in French). Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ a b "France raises heat on decision for next Ariane rocket". Expatica. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ a b Cyrille Vanlerberghe (5 September 2014). "Ariane 6: la version de la dernière chance" (in French). Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (24 September 2014). "ESA's Ariane 6 Cost Estimate Rises with Addition of New Launch Pad". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "ISS Expected To Take Back Seat to Next-gen Ariane as Space Ministers Meet in Zurich". SpaceNews. 22 September 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

The space ministers of France, Germany and Italy are scheduled to meet on September 23 in Zurich to assess how far they are from agreement on strategy and funding for Europe's next-generation Ariane rocket, upgrades to the light-lift Vega vehicle and — as a lower priority — their continued participation in the international space station. The meeting should give these governments a better sense of whether a formal conference of European Space Agency ministers scheduled for December 2 in Luxembourg will be able to make firm decisions, or will be limited to expressions of goodwill.

- ^ Peter B. De Selding (2 December 2014). "ESA Members Agree To Build Ariane 6, Fund Station Through 2017". SpaceNews. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "This Reusable Space Freighter Would 'Open the Door' to European Space Exploration". Gizmodo. 19 September 2022. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Wolny, Marcin (10 January 2016). "Europe in space, 2015 overview". Tech for Space. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Ariane 6 design finalized, set for 2020 launch". Space Daily. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (28 January 2016). "Europe settles on design for Ariane 6 rocket". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ a b de Selding, Peter B. (7 April 2016). "Airbus Safran Launchers aims for "the discipline of the flow" in Ariane 6 integration". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (24 June 2015). "Ariane 6 rockets likely to be assembled horizontally". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

Officials said the preliminary plan calls for the Ariane 6 rocket to be integrated horizontally, a practice long used for Russian launchers and more recently adopted by United Launch Alliance's Delta 4 rocket family and SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (16 December 2015). "Q&A with Stéphane Israël, chairman and CEO of Arianespace". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

When it comes to Ariane 64, we are at around US$90 to US$100 million, as opposed to Ariane 5, which is in terms of cost, around US$200 million. You see with the effort we're making, we want to reduce the cost around 40/50%, which is very ambitious.

- ^ a b Amos, Jonathan (7 April 2016). "Ariane 6 project 'in good shape'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (13 August 2016). "Ariane 6 rocket holding to schedule for 2020 maiden flight". spaceflightnow.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Peach, Matthew (6 November 2015). "Austrian researchers to adapt laser ignition for rockets". optics.org. SPIE Europe. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Henry, Caleb (9 July 2020). "ESA confirms Ariane 6 delay to 2021". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b Elizabeth Howell (3 December 2023). "1st launch of Europe's Ariane 6 rocket finally has June 2024 launch target". Space.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ Parsonson, Andrew (5 June 2024). "Ariane 6 Maiden Flight Scheduled for 9 July". European Spaceflight. Archived from the original on 5 June 2024. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ a b Amos, Jonathan (5 June 2015). "Airbus unveils 'Adeline' re-usable rocket concept". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ "Une version réutilisable d'Ariane 6 est à l'étude" [A reusable version of Ariane 6 is under study] (in French). Futura-Sciences. 9 January 2015. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (13 August 2016). "Ariane 6 rocket holding to schedule for 2020 maiden flight". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ "Ariane 6, the new generation of European launch vehicules [sic]". Ariane Group. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Meddah, Hassan (7 February 2017). Vous avez aimé Ariane 6, vous allez adorer Ariane Next [If you liked Ariane 6, you will love Ariane Next] (Report) (in French). L'Usine nouvelle. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Callisto, Véhicule Spatial Réutilisable" (PDF). CNESmag (in French). No. 68. CNES. May 2016. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Henry, Caleb (8 January 2019). "Arianespace says full Ariane 6 production held up by missing government contracts". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Henry, Caleb (27 February 2019). "OneWeb's first six satellites in orbit following Soyuz launch". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ @jeff_foust (7 May 2019). "Stéphane Israël, Arianespace: ordered first production batch of 14 Ariane 6 rockets yesterday for missions in 2021-23. #SATShow" (Tweet). Retrieved 7 May 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ Ajdin, Adis (27 April 2021). "French pioneering sail-powered boxship". Splash247. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Wind-powered cargo ship completes its first transatlantic crossing". Project Cargo Journal. 21 June 2023. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (3 April 2015). "Desire for Competitive Ariane 6 Nudges ESA Toward Compromise in Funding Dispute with Contractor". SpaceNews. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (4 November 2016). "ESA decision frees up full funding for Ariane 6 rocket". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (9 November 2016). "Full rocket funding unlocked by ESA". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Forrester, Chris (23 January 2020). "EU loans €100m to Arianespace". Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ ESA Space Transport [@ESA_transport] (4 July 2024). "The mass of the dummy payload is 1600 kg and it was built by @ArianeGroup in Les Mureaux, France" (Tweet). Retrieved 9 July 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (10 July 2024). "Europe's Ariane-6 rocket blasts off on maiden flight". BBC. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ a b Stephen Clark (10 July 2024). "Europe's first Ariane 6 flight achieved most of its goals, but ended prematurely". Ars Technica. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Andrew Parsonson (10 July 2024). "Ariane 6 Anomaly Will Have "No Consequence" On Upcoming Missions". European Spaceflight. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ Adrian Beil (10 July 2024). "Ariane 6 successfully launches on maiden flight from French Guiana". NASASpaceflight. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ Wall, Mike (9 July 2024). "Europe's new Ariane 6 rocket launches on long-awaited debut mission". Space.com. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Europe's new Ariane 6 rocket powers into space". European Space Agency. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Foust, Jeff (30 November 2023). "ESA sets mid-2024 date for first Ariane 6 launch". SpaceNews. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ a b c "Arianespace to launch eight new Galileo satellites". Arianespace (Press release). 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Arianespace Ariane 6 to launch Intelsat satellites". Arianespace (Press release). 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Arianespace to launch Australian satellite Optus-11 with Ariane 6". Arianespace (Press release). 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Space Compass and Skyloom Sign a Term Sheet to Bring Optical Data Relay Services to the Earth Observation Market". Business Wire (Press release). 6 September 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Skyloom signs contract with Arianespace for first launch". Arianespace. 27 September 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ @Arianespace (10 September 2021). "We are proud to launch Skyloom's 1st satellite Uhura-1 aboard an Ariane 6 in 2023. This laser-coms relay node will be a game changer for the industry. Congratulations to CEO Marcos Franceschini on this huge milestone" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Jewett, Rachel (26 June 2023). "ESA Awards GMV $218M Contract for Galileo 2nd Gen Ground System". Via Satellite. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "The launch of the new Hellas Sat 5 satellite at the end of 2025 and at the beginning of 2026". News Bulletin. 7 November 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Meteosat series". EUMETSAT. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "EUMETSAT to exploit ESA-developed launchers and flight operations software". EUMETSAT. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter (10 September 2022). "MTG-I 1, 2, 3, 4 (Meteosat 12, 14, 15, 17)". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (12 September 2023). "Arianespace to launch Intelsat small GEO satellite". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ "Planet-hunting eye of PLATO". ESA. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Mission Operations". ESA. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Earth Return Orbiter – the first round-trip to Mars". ESA. 7 April 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "ARIEL moves from blueprint to reality" (Press release). ESA. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (21 October 2022). "ESA finalizes package for ministerial". SpaceNews. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Argonaut – European Large Logistics Lander". ESA. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Athena | Mission Summary". ESA. 2 May 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Athena X-ray observatory | Athena mission". Athena Community Office. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Capturing the ripples of spacetime: LISA gets go-ahead". ESA. 25 January 2024. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Arianespace signs unprecedented contract with Amazon for 18 Ariane 6 launches to deploy Project Kuiper constellation". Arianespace (Press release). 5 April 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (5 April 2022). "Amazon launch contracts drive changes to launch vehicle production". SpaceNews. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b "SENER designs the mechanisms for the assembly of Electra, the first European commercial satellite with electric propulsion". SENER (Press release). 10 September 2019. Archived from the original on 4 January 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Ariane 6 moves to next stage of development". www.esa.int. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "The SpaceX Falcon Heavy Booster: Why Is It Important?". NSS. 3 August 2017. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Berger, Eric (18 April 2023). "Europe's Ariane 6 rocket is turning into a space policy disaster". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Posaner, Joshua; Cerulus, Laurens (17 April 2023). "EU turns to Elon Musk to replace stalled French rocket". Politico. Archived from the original on 14 July 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b Cross, Theresa (3 July 2024). "Europe's Ariane 6 rocket set for maiden voyage amid stiff competition". Space Explored. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Posaner, Joshua (1 July 2024). "Europe smarts as Elon Musk's SpaceX wins key satellite deal". Politico. Archived from the original on 8 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Castel, Frédéric (24 June 2024). "Europe aims to end space access crisis with Ariane 6's inaugural launch". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

External links[edit]

- Ariane 6 - Official Website

- Ariane 6 concept video, Airbus Safran Launchers, November 2016.

- Airbus Defence and Space presents Ariane 6 at Paris Air Show 2015

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch