Maqil

| Banu Ma'qil بَنُو مَعقِل | |

|---|---|

| Madhhaji Arab tribe | |

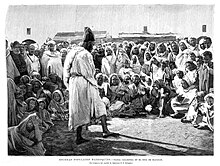

The tribe in 1894. | |

| Ethnicity | Arab |

| Nisba | al-Ma'qili المعقلي |

| Location | Yemen, Morocco, Mauritania, Algeria, Western Sahara |

| Parent tribe | Banu Madhhaj |

| Branches | |

| Language | Arabic |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

The Banu Ma'qil (Arabic: بنو معقل) is an Arab nomadic tribe that originated in South Arabia.[1] The tribe emigrated to the Maghreb region of North Africa with the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym tribes in the 11th century. They mainly settled in and around the Saharan wolds and oases of Morocco; in Tafilalt, Wad Nun (near Guelmim), Draa and Taourirt. With the Ma'qil being a Bedouin tribe that originated in the Arabian Peninsula, like Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, they adapted perfectly to the climatic desert conditions of the Maghreb, discovering the same way of life as in the Arabian Peninsula.[1] The Ma'qil branch of Beni Hassan which came to dominate all of Mauritania, Western Sahara, south Morocco, and south-west Algeria, spread the Hassaniya Arabic dialect,[2] which is very close to classical Arabic.[1]

Origins

[edit]The exact origin of the Ma'qil tribe is unknown,[3] although it has been established that they most likely originated in South Arabia (Yemen).[1] They claimed for themselves a prestigious Hashemite descent from Ja'far ibn Abu Talib, son of Abu Talib and brother of Ali ibn Abu Talib. Some Arabian genealogists categorized them as Hilalians.[3] Ibn Khaldun hypothesized that both of these versions are false, since the Hashemites lived in urban cities and weren't nomadic nor ever wandered in the desert.[3] He added that the Ma'qil is a name only found in Yemen.[3] Ibn Khaldun said that they were likely an Arab nomadic group from Yemen, and this is supported by Ibn al-Kalbi and Ibn Said.[3][4] Ibn Khaldun noted "the origin of the Ma'qil tribe is from the Arabs of Yemen, and their grandfather is Rabi'a bin Ka'b bin Rabi'a bin Ka'b bin al-Harith, and from al-Harith bin Ka'b bin 'Amr bin 'Ulah bin Jald bin Madhhij bin Adad bin Zayd bin Kahlan".[5]

Sub-tribes

[edit]Beni Ubayd Allah

[edit]The Banu Ubayd Allah descended from Ubayd Allah bin Sahir (or Saqil), son of the Ma'qil forefather.[4] They were the biggest sub-group of the Ma'qil and lived as nomads in the southern hills between Tlemcen and Taourirt.[6] In their nomadic travel they reached as far as the Melwiya river in the north and Tuat in the south.[6] The Beni Ubayd Allah later divided into two sub-tribes: The Haraj and The Kharaj.[7]

Beni Mansur

[edit]The Banu Mansur descended from Mansour bin Mohammed, the second son of the Ma'qil forefather.[8][9] They lived as nomads between Taourirt and the Draa valley.[9] At one time they controlled the area between the Moulouya river and Sijilmasa, in addition to Taza and Tadla.[9] They were the second most numerous Ma'qil sub-tribe after the Beni Ubayd Allah.[8]

Beni Hassan

[edit]The Banu Hassan descended from Hassan bin Mokhtar bin Mohamed, the second son of the Ma'qil forefather.[4] They were thus the cousins of Beni Mansour. The Banu Hassan sub-tribe is, however, not limited to the descendants of Hassan, they also include the Shebanat (sons of Shebana the brother of Hassan) and the Reguitat who descended from the other sons of Mohamed; namely Jalal, Salem and Uthman.[4][10] They wandered in the Sous and the extreme-Sous (present-day southern Morocco)[9] but they had originally lived as nomads near the Melwiya river neighboring their relatives; the Banu Ubayd Allah and Banu Mansour.[10] Their coming to the Sous was a result of the Almohad governor of this region who invited them to fight for him when a rebellion broke out.[10]

Thaaliba

[edit]The Thaaliba were the descendants of Thaalab bin Ali bin Bakr bin Sahir (or Saqir or Suhair) son of the Ma'qil forefather. This sub-tribe settled in a region close to Algiers, the Mitidja plain. They came to rule Algiers from 1204 to 1516 until the Ottomans took over control from Salim al-Tumi in the capture of Algiers.[11]

Emigration to the Maghreb

[edit]The Ma'qils entered the Maghreb during the wave of emigration of the Arabian tribes (Banu Hilal, Banu Sulaym, etc.) in the 11th century.[9] They adapted to the climatic desert conditions of the Maghreb, discovering the same way of life as in the Arabian Peninsula.[1] The Banu Sulaym opposed their arrival and fought them off.[12] They later allied with the Banu Hilal and entered under their protection,[9] which enabled them to wander in the Moroccan Sahara between the Moulouya River and Tafilalet oases.[9] A tiny group of them however stayed in Ifriqiya, during their westward transit in the Maghreb, and briefly worked as viziers of the victorious Hilalians and Banu Sulaym, who had recently defeated the powerful Berber Zirid Empire.[9]

Harry Norris noted "the Moorish Sahara is the western extremity of the Arab World. Western it certainly is, some districts further west than Ireland, yet in its way of life, its culture, its literature and in many of its social customs, it has much in common with the heart lands of the Arab East, in particular with the Hijaz and Najd and parts of the Yemen".[13]

The Ma'qils quickly grew in numbers, this is due to the fact that parts of many other Arabian tribes joined them, which included:[3]

- Fezara of Asheja

- Chetha of Kurfa

- Mehaya of Iyad

- Shuara of Hassin

- Sabah of al-Akhdar

- Some of Banu Sulaym

Once in Morocco, they allied with the Zenata nomadic groups that neighbored them in the wolds. After the decline of Almohad authority, the Ma'qil took advantage of the civil war between the different Zenata groups and seized control of various Ksours and oases in the Sous, Draa, Tuat and Taourirt upon which they imposed taxes, while giving a certain amount of the collected money to the local competing Zenata kings.[3]

Evolution under the Almohads

[edit]During the Almohad era, the Ma'qils stayed loyal, paid taxes and neither looted nor attacked any villages, Ksours or passing trading Caravans.[3] As the power of the Almohads declined, the Ma'qils took advantage of the lack of central state authority and the civil war between the Zenata, and seized the control of many Ksours around Tafilalet, the Draa Valley and Tawrirt.[3][14]

Almohad caliph Abd al-Mu'min encouraged the settlement of Banu Ma'qil and other Arabian tribes in coastal Morocco, an area which was largely depopulated by the conquest of the Barghawata by the Almohads.[15] The migration and presence of Arab nomads led to further Arabic influence and added an important element to the local power equation, of which when one of the Marinid sultans went in public procession, he was escorted by a Zenata on one side and an Arab on the other.[15]

Evolution under the Zayyanids and Marinids

[edit]The Kharaj of Banu Ubayd Allah initially opposed the Zayyanids,[6] but later allied with them after they were defeated in a battle with the sultan, Ibn Zyan,[6][7] When the Marinids replaced the Zayyanids, the Kharaj remained faithful to the Zayyanids since they had given them tax collection privileges.[7] The Marinid Sultan, Abu al-Hassan then stripped them of these acquired advantages and gave them instead to the Beni Iznassen tribe,[7] which resulted in a rebellion by the Kharaj which killed the Marinid governor of the Saharan Ksours, Yahya ibn Al-iz.[7][16]

As the Arabs expanded their domains in Morocco and Arabized many Berbers, Arabic became the common language, which the Marinids made the official language.[17] Arabs also increased their influence and power in Morocco, and no one could have ruled there without their co-operation.[17] When riding in state, the Marinid sultan was flanked on either side by an Arab and a Zenata chief as a symbol of the dual character of the Makhzen.[17]

Migration to Mauritania

[edit]In the 14th and 15th centuries, the nomadic Arab tribes of Banu Ma'qil moved into Mauritania and were over time able to establish complete dominance over the Berbers[18] after defeating both Berbers and Black Africans in the region and pushing them to the Senegal river.[19] An extensive Arabization of Mauritania started following the Arab victory in the Char Bouba war in 1677.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Sabatier, Diane Himpan; Himpan, Brigitte (2019-03-31). Nomads of Mauritania. Vernon Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-1-62273-410-8.

- ^ Ould-Mey, Mohameden (1996). Global Restructuring and Peripheral States: The Carrot and the Stick in Mauritania. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8226-3051-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 78.

- ^ a b c d Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 79.

- ^ Khaldûn, Ibn (2015-04-27). The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History - Abridged Edition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16628-5.

- ^ a b c d Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 81.

- ^ a b Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 77.

- ^ a b c Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 91.

- ^ بن عتو, حمدون (2017-03-20). "الثعالبة في الجزائر من خلال المصادر المحلية د. حمدون بن عتو". الحوار المتوسطي (in Arabic). 8 (1): 437–445. ISSN 2571-9742.

- ^ Robinson, David (2010). Les sociétés Musulmanes Africains. p. 140.

- ^ Ould-Mey, Mohameden (1996). Global Restructuring and Peripheral States: The Carrot and the Stick in Mauritania. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8226-3051-7.

- ^ Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 92.

- ^ a b Isichei, Elizabeth (1997-04-13). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-521-45599-2.

- ^ Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 82.

- ^ a b c Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050. Cambridge University Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- ^ Gall, Timothy L. (November 2006). Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations. Thomson Gale. ISBN 978-1-4144-1089-0.

- ^ Lombardo, Jennifer (2021-12-15). Mauritania. Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-5026-6305-4.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch