Box Tunnel

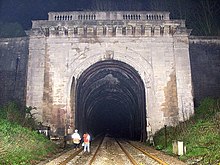

A winter view of the western portal | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | Great Western Main Line |

| Location | Box Hill, Wiltshire, England |

| Coordinates | 51°25′17″N 2°13′34″W / 51.42128°N 2.22617°W |

| Status | Open, operational |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | December 1838 |

| Opened | 30 June 1841 |

| Owner | Network Rail |

| Operator | Network Rail |

| Technical | |

| Length | 1.83 miles (2.95 km) |

| Operating speed | 125 miles per hour (201 km/h) |

| Grade | 1:100 |

Box Tunnel passes through Box Hill on the Great Western Main Line (GWML) between Bath and Chippenham. The 1.83-mile (2.95 km) tunnel was the world's longest railway tunnel when it was completed in 1841.

Built between December 1838 and June 1841 for the Great Western Railway (GWR) under the direction of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the straight tunnel descends on a 1 in 100 gradient from its eastern end. At the time the tunnel's construction was considered dangerous due to its length and the composition of the underlying strata. The west portal is Grade II* listed[1] and the east portal is Grade II listed.[2]

Ammunition was stored near the tunnel during World War II, reusing mine workings. During the 2010s, the tunnel was modified and the track lowered to prepare it for electrification, although in 2016, this plan has been suspended for the time being.[3][4]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]During the 1830s, Isambard Kingdom Brunel developed a plan for a railway running east–west between London and Bristol.[5] The Great Western Main Line would maintain either level ground or gentle gradients of no greater than 1 in 1000 along most of its route. Between Swindon and Bath, at the highest point of the line, a tunnel was proposed through Box Hill, outside Corsham.[5]

The tunnel would have a gradient of 1 in 100. At the time, the use of such a steep gradient inside the tunnel allegedly provoked criticism by some of Brunel's contemporaries.[5] Box Tunnel would be the longest railway tunnel at almost 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) in length.[5]

Geology

[edit]While a tunnel had been included in the 1835 Great Western Railway Act, contemporary engineers considered the construction of Box Tunnel to be an impossibility at worst and a dangerous undertaking at best. The challenge posed was not only its length but the difficult underlying strata it would have to pass through. The rocks through which it passes comprise Great Oolite overlying fuller's earth, and Inferior Oolite and Bridport Sand beneath, a combination with which tunnellers were familiar.

The Great Oolite limestone, known as Bath Stone, is easily worked and had been used for construction since Roman times. In the 17th and 18th centuries it was extracted by the room and pillar method and used for many buildings in Bath, Somerset.[6] To assess the geology more accurately, between 1836 and 1837, Brunel sank eight shafts at intervals along the tunnel's projected alignment.[7]

Construction

[edit]The GWR selected George Burge of Herne Bay as the major contractor,[7] being responsible for undertaking 75 per cent of overall tunnel length, working from the western end. Burge appointed Samuel Yockney as his engineer and manager.[8] Locally based Lewis and Brewer were responsible for the remainder, starting from the eastern side. One of Brunel's personal assistants, William Glennie, was in overall charge until completion.[5]

In December 1838, construction started. Work was divided into six sections; access to each was via a 25-foot-diameter (7.6 m) ventilation shaft, which ranged in depth from 70 feet (21 m) at the eastern end to 300 feet (91 m) towards the western end.[7] The men, equipment, materials and 247,000 cubic yards (189,000 m3) of extract had to go in and come out of the shafts assisted by steam-powered winches. The shafts were the safety exits from the tunnel.[7]

Candles provided the only lighting in the workings and were consumed at a rate of one tonne per week, which was equalled by the weekly consumption of explosives.[7] Due to the considerable time required for men to enter and exit the workings, blasting took place while they were in the tunnel. This practice and water ingress exceeding the calculated volumes, has been attributed as causing most of the deaths that occurred. About 100 navvies were killed during the tunnel's construction. Additional pumping and drainage were required during and after its construction. Large amounts of water entering the tunnel in the winter months impeded progress.[7][5]

Once the eastern section had been blasted out, it was cut to form a gothic arch and left unlined.[5] The western section was excavated using picks and shovels and the walls were lined with brick. Over 30 million bricks were used which were manufactured in nearby Chippenham[clarification needed] and transported in horse-drawn carts. Horses were used to remove much of the spoil.[5]

The restrictions imposed by the site contributed to a delay in the tunnel's completion. By August 1839, only 40 per cent of the works had been finished.[7] By summer 1840, the London Paddington to Faringdon Road section of the Great Western Main Line (GWML) had been completed, as was the track from Bath to Bristol Temple Meads. The Box Tunnel was the last section of the GWML to be finished, although not for lack of effort on the part of Brunel.[5]

During January 1841 Brunel came to an agreement with Burge and Yockney to increase their workforce from 1,200 to 4,000, and the tunnel was completed in April 1841.[7] The completed tunnel was 30 feet (9.1 m) wide and capable of accommodating a pair of broad-gauge tracks. When the ends of the tunnel were joined, there was less than 2 inches (50 mm) of error in their alignment.[7] Brunel was so delighted that he reportedly removed a ring from his finger and gave it to the works foreman.[5]

Opening

[edit]On 30 June 1841, the tunnel was opened to traffic with little in the way of ceremony. A special train departed London Paddington and traversed the whole of the GWR to complete the first rail journey to Temple Meads Station in Bristol in about four hours.[5]

After the opening, for several months, work continued to finish the tunnel's western portal near Box, Wiltshire which Brunel had designed in a grand classical style – grander than the eastern portal as it is in full view of the London to Bath road. The height of the opening is far in excess of what was required (and indeed reduces once inside), but it gives the feel of a generous celebratory monument to a new form of travel. That height has been further accentuated with the 2015 lowering of the trackbed for electric catenary to be installed.[9] The eastern portal at Corsham has a more modest brick face, with rusticated stone dressings.[7]

Commentators and critics voiced concerns and disapproval about the unlined section of the tunnel; they believed that it lacked solidity and was a danger to traffic.[5] The GWR responded to these complaints by building a brick arch underneath part of the unlined section close to the entrance which was prone to frost damage. Some areas of the tunnel remain unlined.[5]

Brunel's birthday

[edit]

GWR franchise rebutted the theory that the rising sun passed through the tunnel on Isambard Brunel's 9 April birthday, finding in 2017 that the sunrise did not shine fully through the tunnel. Librarian C.P. Atkins calculated in 1985 that full illumination through Box Tunnel would occur on 7 April in non-Leap years and on 6 April in Leap years.[10] The Society of Genealogists in 2016 suggested the sun shone through the tunnel on 6 April, the birthday of Brunel's sister, Emma Joan Brunel, three years out of four during the 1830s.[citation needed][11]

Defence use

[edit]Starting in 1844, the hill surrounding the tunnel was subject to extensive quarrying to extract Bath stone for buildings. In the run-up towards the Second World War, the need to provide secure storage for munitions at distributed locations across the UK was recognised. During the 1930s, a proposal to create three Central Ammunition Depots (CADs) was submitted: one in the north (Longtown, Cumbria); one in the Midlands (Nesscliffe, Shropshire); and one in the South of England at Tunnel quarry, Monkton Farleigh and Eastlays Ridge.[12]

During the 1930s, Tunnel Quarry was renovated by the Royal Engineers as one of the three major stockpiles. During November 1937, the GWR was contracted to build a 1,000-foot-long (300 m) raised twin-loading platform at Shockerwick for Monkton Farleigh and two sidings branching from the Bristol–London mainline just outside the tunnel's eastern entrance at 51°24′19.31″N 2°17′22.94″W / 51.4053639°N 2.2897056°W. Thirty feet (9.1 m) below and at right angles to this point, the War Office had built a narrow-gauge wagon-sorting yard which accessed a 1.25-mile (2.0 km) tunnel, built by the Cementation Company, descending at a rate of 1 in 8.5 to the Central Ammunition Depot in the former quarry workings. The logistics operation was designed to cope with a maximum of 1,000 tons of ammunition per day.[13]

A Royal Air Force station, RAF Box, was established and used an area of the tunnels.[13] In response to the Bristol Blitz, during 1940, Alfred McAlpine developed a fallback aircraft engine factory for use by the Bristol Aeroplane Company (BAC), although it never went into production.[13] BAC used the facility to accommodate the company's experimental department, which was developing an engine to power bombers and the Bristol Beaufighter.[14]

The CAD was closed at the end of the war but was maintained in operational condition until the 1950s. The sidings were cleared, and saw no further use until the mid-1980s when a museum was opened on the site for a short period. During the post-war years, portions of the ammunition depot were redeveloped for other facilities, including the Central Government War Headquarters, RAF No.1 Signal Unit, Controller Defence Communication Network and the Corsham Computer Centre.[13]

As of the present day, the only element of the complex that remains is the former computer centre. The visible north end of the tunnel has been sealed by concrete and rubble. The former CAD has been reused as a secure commercial document storage facility.[13]

Electrification

[edit]The tunnel was planned to be electrified by 2017 as part of the Great Western Electrification Programme. During the summer of 2015, the tunnel was closed for six weeks for preparatory work including lowering the track by roughly 600 millimetres (24 in) and replacing 7 miles (11 km) of cabling in advance of the catenary infrastructure being installed.[4][15] However a November 2016 announcement stated that the plan to electrify the mainline from Thingley Junction (near Chippenham) to Bristol Temple Meads was delayed indefinitely.[16]

Geographical location

[edit]- East portal: 51°25′25″N 2°12′19″W / 51.423685°N 2.20536°W

- Ventilation shaft: 51°25′22″N 2°12′47″W / 51.42277°N 2.21303°W

- Ventilation shaft: 51°25′18″N 2°13′18″W / 51.42176°N 2.22179°W

- Centre of tunnel: 51°25′17″N 2°13′34″W / 51.42128°N 2.22617°W

- Ventilation shaft: 51°25′15″N 2°13′48″W / 51.42084°N 2.23010°W

- Ventilation shaft: 51°25′11″N 2°14′23″W / 51.41970°N 2.23982°W

- West portal: 51°25′08″N 2°14′49″W / 51.41888°N 2.24698°W

Box Tunnel in fiction

[edit]- The 2nd episode of the 2nd series of McDonald & Dodds takes place in and around Box Tunnel (although called Box Hill Tunnel). The legend of the sunrise at Brunel's birthday also has an important role for both the setting and the plot.

See also

[edit]- List of tunnels in the United Kingdom

- Stapleford Miniature Railway 1/5 railway featuring stone replica of Box tunnel

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Historic England, "West Portal of Box Tunnel (1271441)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 11 April 2017

- ^ Historic England, "Box Tunnel East Portal (MLN19912) (1271441)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 11 April 2017

- ^ Department for Transport (2009). Britain's transport infrastructure: Rail electrification (PDF). London: DfT Publications. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-84864-018-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Box tunnel reopens after Network Rail electrification work". BBC News. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Manolson, Adam. "Box Tunnel". Engineering Timelines. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Combe Down Stone Mines Land Stabilisation Project". BANES. Archived from the original on 17 January 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Box Tunnel". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Samuel Hansard Yockney". GracesGuide.co.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Dunn, Tim (26 August 2020). "Great railway bores of our time!". RAIL. No. 912. Peterborough: Bauer Media Group. pp. 42–49.

- ^ Atkins, C.P. (1985). "Box Railway Tunnel and I. K. Brunel's Birthday: A Theoretical Investigation". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 95 (6): 260–262. Bibcode:1985JBAA...95..260A.

- ^ "Isambard's Gift". Mirli Books. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Corsham Tunnels — A brief guide" (PDF). gov.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "CAD Monkton Farleigh". subbrit.org.uk. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Gray, Tony (1987). The Road to Success: Alfred McAlpine 1935 – 1985. Rainbird Publishing.

- ^ Carr, Colin. "Preparing the way for Bath electrification." Archived 14 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine railengineer.uk, 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Great Western line electrification 'deferred' amid cost overruns". The Guardian. 8 November 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adley, R. (1988). Covering My Tracks. Stephens. pp. 54–77. ISBN 0-85059-882-6.

- Buchanan, R. Angus (2002). Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Hambledon and London. ISBN 1-85285-331-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chittenden, Maurice (30 October 2005). "For sale: Britain's underground city". The Times. Retrieved 18 May 2007.[dead link]

- Hennessy, Peter (2002). The Secret State – Whitehall and the Cold War. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-100835-0.

- Karlson, Stephen H. (3 February 1999). "Re: Six More Weeks of Prelims". Northern Illinois University message board. Archived from the original on 3 December 2000. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- Lushman, Rory (1999). "The Box Hill Tunnel: An Anorak's Paradise or a Passage To Narnia?". Archived from the original on 7 November 2002.

- McCamley, Nick (2000). Secret Underground City. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 0-85052-733-3.

External links

[edit]- Map sources for Box Tunnel

- Network Rail Virtual Archive: Box Tunnel, engineering drawings of tunnel

- Subterranea Britannica entry on the Corsham bunkers

- Brunel portal

- Tunnel does align, but 3 days before Brunel's birthday; however the sky is not visible through it, detailed analysis of the alignment

- Wiltshire's Secret Underground City: Burlington Articles, interactive map and video tour from BBC Wiltshire

- The light at the end of the tunnel. How Brunel designed his memorial into the Box Tunnel, which is aligned with the sun on his birthday, 9 April.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch