Casimir Goerck

Casimir Theodor Goerck[1] (born c. 1755[2] – died November 19 or December 11, 1798) was one of a handful of officially recognized "city surveyors" for New York City from 1788 until his death from yellow fever in 1798. Goerck was related to the Roosevelt family by marriage, having married Elizabeth Roosevelt, by whom he had two children, a daughter, Henrietta, and a son, Theodore.[2]

Career

[edit]Goerck was of Polish or German origin, and had come to America to be an artillery officer for the Continental Army in the American Revolution.[2] According to Stokes's The Iconography of Manhattan Island, Goerck first appeared on the New York scene in 1785.[3]

That year, the city's Common Council hired Goerck to survey and lay out lots and streets in the city's "Common Lands", about 1,300 acres (530 ha), or approximately 9% of the Manhattan island, which was what remained of land granted to the colony of New Amsterdam by the Dutch provincial government. The Common Lands were landlocked with no access to the rivers, and of poor quality, either rocky and elevated or swampy and low-lying. The Council hoped that by providing streets to access the new lots, they could sell them and provide the city with a needed stream of income. Despite the difficulty of the task due to the topography and ground cover, as well as the relatively primitive tools available to surveyors at the time, Goerck finished the job in about 6 months, by December 1785. He had created 140 five-acre (2.0 ha) lots – the size he was instructed to create – of varying uniformity, and had laid out a road through the middle of them that would, eventually, become Fifth Avenue in the Commissioners' Plan of 1811. Goerck's lots were oriented with the long axis going east-west, just as the five-acre (2.0 ha) blocks in the Commissioners Plan would be.[4]

In 1788, Goerck was hired by the long-established Bayard family, relatives of Peter Stuyvesant, to survey and lay out streets in the portion of their estate west of Broadway, so the land could be sold in lots. About 100 acres (40 ha) accommodated 7 east-west and 8 north-south streets, all 50 feet (15 m) wide, making up 35 whole or partial rectilinear blocks of 200 feet (61 m) width from east to west, and between 350 and 500 feet (110 and 150 m) long north to south – although near the edges of the estate the grid broke down in order to connect up with existing streets. The Bayard street grid was one of the first attempts to apply a gridiron plan to Manhattan island, and the streets still exist as the core of SoHo and part of Greenwich Village: Mercer, Greene, and Wooster Streets, LaGuardia Place/West Broadway (originally Laurens Street), and Thompson, Sullivan, MacDougal, and Hancock Streets, although the last has been subsumed by the extension of Sixth Avenue.[5]

By 1794, with the economy of the city improving and hoping for increased sales of Common Lands lots, the Council again hired Goerck to survey the area. Goerck was asked to make the lots more regular and rectangular, and to add roads to the east and west of his original middle road – these would become Fourth and Sixth Avenues when the Commissioners' Plan came out. He was also to lay out east-west streets connecting the three north-south roads, which would later become the numbered streets of the 1811 plan. Goerck took 2 years to complete this task, finishing in March 1796. The Common Lands were now divided into 212 numbered lots of a size close to 5 acres (2.0 ha), although, again, the surveying was less than perfect. In 1808, John Hunn, the city's street commissioner at the time, would comment that "The Surveys made by Mr. Goerck upon the Commons were effected through thickets and swamps, and over rocks and hills where it was almost impossible to produce accuracy of mensuration." Often the streets intended to intersect at right angles would not quite do so.[6]

Nevertheless, Goerck's two surveys of the Common Lands provided a template for the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, although the Commission did not acknowledge this in their report. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission has written that "The Commissioner's Plan borrowed heavily from Goerck's earlier surveys and essentially expanded his scheme beyond the common lands to encompass the entire island."[7] Historian Gerard Koeppel comments "In fact, the great grid is not much more than the Goerck plan writ large. The Goerck plan is modern Manhattan's Rosetta Stone..."[8]

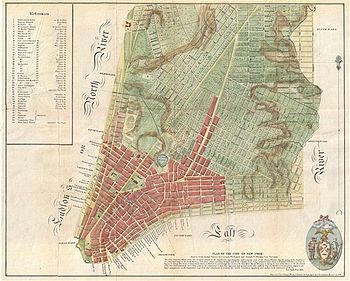

With the French architect Joseph-François Mangin, another of the five city surveyors, Goerck was commissioned by the Common Council in 1797 to prepare a new map of the city as it existed. Goerck and Mangin had each submitted individual proposals to the Council, but then decided to team up. Their new joint proposal offered to provide a detailed map as far north as today's Astor Place, with elevations throughout – correcting miscalculations of elevation which had previously been accepted – and indications of the positions of every lot, house, street, wharf, square and ward. They asked for 18 months to do the job, and wanted $3,000 in compensation (equivalent to $72 in 2023). They would provide a six-foot (1.8 m) square master map, as well as three-foot (0.91 m) square copies, and a field book containing all the pertinent information, including that of the names of property owners, and a method for correcting past miscalculations. The Council awarded them the job.[9]

Goerck died of yellow fever before the map could be completed[10] and Mangin finished it on his own, adding Mangin Street and Goerck Street as well as other improvements and additions that went far beyond the project commissioned by the Council.[11] This proved to be the downfall of the project: after four years in which the Council had accepted the plan as "the new Map of the City," political machinations perhaps organized by Aaron Burr brought the plan's speculative nature into disrepute – although there was no question that the map showed the settled area of the city accurately, it was Mangin's expansion of the Council's commission to show "not the plan of the City such as it is, but such as it is to be." There is no indication of whether Goerck approved of this or not.[12]

Death

[edit]According to Stokes, Goerck died on November 19, 1798,[3] which roughly accords with Koeppel, who writes

Before a freeze in late November 1798 killed them, mosquitoes delivered death bites to two thousand of the sixty thousand New Yorkers. Casimir Goerck, who spent long hours tramping the filthy streets, foul docksides, and swampy outskirts, was among them, early in the month.[10]

Cohen and Augustyn give December 11, 1798 for the date of Goerck's death.[13]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ For "Theodor" and not "Thomas" see Koeppel (2015), p.20

- ^ a b c Koeppel (2015), pp.20-21

- ^ a b Stokes, Isaac Newton Phelps. (1915) The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909. New York: Robert H. Dodd. p. 607.

- ^ Koeppel (2015), pp.18-22

- ^ Koeppel (2015), pp.14-16

- ^ Koeppel (2015), pp.25-26

- ^ Brazee, Christopher D. and Most, Jennifer L. (March 23, 2010) Upper East Side Historic District Extension Designation Report New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, p.6 n.12

- ^ Koeppel (2015), p.27

- ^ Koeppel (2015), pp.34-36

- ^ a b Koeppel (2015), p.34

- ^ 1801 Mangin-Goerck Plan or Map of New York City. Geographicus Rare Antique Maps. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Koeppel (2015), p.37 and passim

- ^ Cohen, Paul E. & Robert T. Augustyn (2014). Manhattan in Maps 1527-2014. Mineola: Dover Publications. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-486-77991-1.

Bibliography

- Koeppel, Gerard (2015). City on a Grid: How New York Became New York. Boston: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82284-1.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch