Charles Radbourn

| Charles Radbourn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: December 11, 1854 Rochester, New York, U.S. | |

| Died: February 5, 1897 (aged 42) Bloomington, Illinois, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| May 5, 1880, for the Buffalo Bisons | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 11, 1891, for the Cincinnati Reds | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 310–194 |

| Earned run average | 2.68 |

| Strikeouts | 1,830 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1939 |

| Election method | Old-Timers Committee |

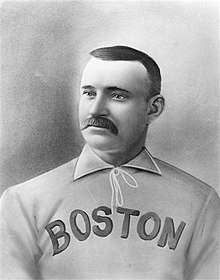

Charles Gardner Radbourn (December 11, 1854 – February 5, 1897), nicknamed "Old Hoss", was an American professional baseball pitcher who played 12 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). He played for Buffalo (1880), Providence (1881–1885), Boston (National League) (1886–1889), Boston (Player's League) (1890), and Cincinnati (1891).

Born in New York and raised in Illinois, Radbourn played semi-professional and minor league baseball before making his major league debut for Buffalo in 1880. After a one-year stint with the club, Radbourn joined the Providence "Grays." During the 1884 season, Radbourn won 60 games, setting an MLB single-season record that has never been broken, or even seriously approached. He also led the National League (NL) in earned run average (ERA) and strikeouts to win the Triple Crown, and the Grays won the league championship. After the regular season, he helped the Grays win the 1884 World Series, pitching every inning of the three games.

In 1885, when the Grays team folded, the roster was transferred to NL control, and Radbourn was claimed by Boston. He spent the next four seasons with the club, spent one year with the Boston franchise of the single-season Players' League, and finished his MLB career with Cincinnati. Radbourn was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.

Early life

[edit]Radbourn was born on December 11, 1854, in Rochester, New York, the second of eight children to Charles and Caroline (Gardner) Radbourn.[1] Charles Radbourn (the elder) had immigrated to the United States from Bristol, England, to find work as a butcher; Caroline followed soon after.[2]

In 1855, the Radbourn family moved to Bloomington, Illinois, where Radbourn was raised. As a teenager, Radbourn worked as a butcher with his father, and as a brakeman for the Indiana, Bloomington and Western Railway company.[3]

Early baseball career

[edit]In 1878, Radbourn joined the Peoria Reds, a barnstorming team, as their right fielder and "change pitcher". No substitutions were allowed at the time so if the starting pitcher became ineffective in the late innings the change pitcher, usually playing right field, would exchange positions with the starter to try to save the game. In 1879 he signed with Dubuque in the newly formed Northwest League. Radbourn made the major leagues in 1880 as second baseman, right fielder and change pitcher for the Buffalo Bisons of the National League. He played in six games, batted .143, and never pitched an inning, but practiced so hard he developed a sore shoulder and was released. When he recovered, he pitched for a pick-up Bloomington team in an exhibition game against the Providence Grays. He impressed everyone so much that Providence signed him on the spot for a salary variously reported as $1,100 or $1,400.[4]

Providence Grays

[edit]1881–1883

[edit]During Radbourn's first season with the Grays in 1881, he split pitching duties with John Montgomery Ward. Radbourn pitched 325.1 innings and compiled a win–loss record of 25–11. He became the team's primary pitcher in 1882, pitching 466 innings and going 33–19 with a 2.11 earned run average. He led the NL with 201 strikeouts and six shutouts and was second-best in wins and ERA. In 1883, he pitched 632.1 innings and led the league in wins, going 48–25. His 2.05 ERA and 315 strikeouts both ranked second in the NL.[5]

1884 season

[edit]

When Providence failed to win the pennant in 1883, the franchise was on shaky financial ground. Ownership brought in a new manager, Frank Bancroft, and made it plain: win the pennant or the team would be disbanded.

Early in the season, Radbourn shared pitching duties with Charlie Sweeney. Radbourn, who had a reputation for being vain, became jealous as Sweeney began to have more success, and the tension eventually broke out into violence in the clubhouse. Radbourn was faulted as the initiator of the fight and was suspended without pay after a poor outing on July 16, having been accused of deliberately losing the game by lobbing soft pitches over the plate. But on July 22, Sweeney had been drinking before the start of the game and continued drinking in the dugout between innings. Despite being obviously intoxicated, Sweeney managed to make it to the seventh inning with a 6–2 lead; when Bancroft attempted to relieve him with the change pitcher, Sweeney verbally abused him before being ejected and storming out of the park, leaving Providence with only eight players. With only two players to cover the three outfield positions, the Grays lost the lead, then lost the game.[6]

Afterward, Sweeney was kicked off the Grays, and this left the team in a state of disarray with the consensus view that the team should be disbanded. At that point, Radbourn offered to start every game for the rest of the season (having pitched in 76 of 98 games the season before)[7] in exchange for a small raise and exemption from the reserve clause for the next season. From that point, July 23 to September 24 when the pennant was clinched, Providence played 43 games and Radbourn started 40 of them and won 36. Soon, pitching every other day as he was, his arm became so sore he couldn't raise it to comb his hair. On game day he was at the ballpark hours before the start, getting warmed up. He began his warm up by throwing just a few feet, increasing the distance gradually until he was pitching from second base and finally from short center field.[8]

Radbourn finished the season with a league-leading 678.2 innings pitched and 73 complete games, and he won the Triple Crown with a record of 60–12, a 1.38 earned run average, and 441 strikeouts. His 60 wins in a season is a record which is expected never to be broken because no starter has made even as many as 37 starts in a season since Greg Maddux did so in 1991.[9] Also, his 678.2 innings pitched stands at second all-time, behind only Will White (680 in 1879) for a single season.

After the regular season ended, the NL champion Grays played the American Association champion New York Metropolitans in the 1884 World Series. Radbourn started each game of the series and won all three, while allowing just three runs, all unearned.[10]

Statistical notes

[edit]

There is a discrepancy in Radbourn's victory total in 1884. The classic MacMillan Baseball Encyclopedia, the current edition of The Elias Book of Baseball Records, his National Baseball Hall of Fame biography, and Baseball-Reference.com all credit Radbourn with 60 wins (against 12 losses).[11] Other sources, including Baseball Almanac, MLB.com, and Edward Achorn's 2010 book, Fifty-nine in '84, give Radbourn 59 wins. Some older sources (such as his tombstone plaque) counted as high as 62. There is no dispute about the 678+2⁄3 innings pitched, only over the manner in which victories were assigned to pitchers; the rules in the early years allowed more latitude to the official scorer than they do today.

According to at least two accounts, in the game of July 28 at Philadelphia, Cyclone Miller pitched five innings and left trailing, 4–3. Providence then scored four runs in the top of the sixth. Radbourn came in to relieve, and pitched shutout ball over the final four innings, while the Grays went on to score four more and win the game, 11–4. The official scorer decided that Radbourn had pitched the most effectively, and awarded him the win. Under the rules of the day, the scorekeeper's decision certainly made sense. However, under modern scoring rules, Miller would get the win, being the "pitcher of record" when he left the game, and Radbourn would have been credited with a save for closing the game and "pitching effectively for three or more innings". Some modern sources retroactively awarded the win to Miller.

1885 season

[edit]Radbourn pitched effectively in the majors for several more years but was not able to duplicate his success of 1883 and 1884. In 1885, he pitched 445.2 innings and went 28–21. The Grays folded after the season, and the roster was transferred to NL control.

Later baseball career

[edit]Radbourn was claimed by Boston, and he spent the next four seasons with the club, winning 27, 24, 7, and 20 games. He then jumped to the rebel Players' League and spent 1890 with its Boston club and, after the PL folded, played the 1891 season with Cincinnati, where he recorded his 300th victory before retiring. Radbourn's career record was 310–194.

Later life and legacy

[edit]

After retiring from baseball, Radbourn opened up a successful billiard parlor and saloon in Bloomington, Illinois. He was seriously injured in a hunting accident soon after retirement, in which he lost an eye. He died in Bloomington on February 5, 1897, at age 42, and was interred in Evergreen Cemetery.[12]

Radbourn was posthumously inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939. In 1941, a plaque was placed on the back of his elaborate headstone, detailing his distinguished career in baseball.[12] In the 2001 book The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James ranked Radbourn as the 45th-greatest pitcher of all time.

It is speculated Radbourn might be the namesake of the charley horse, a painful leg cramp not unlike that from which he suffered.[13] While the term charley horse does come about from the time he was playing baseball and new articles of the time mentioning "the new disease" seem to always relate it to baseball players, it seems to be because "Charley" was for horses as "Rover" is for dogs and a reference to the stiff-leggedness that the condition forces on those who are experiencing it.[14]

Radbourn is also known for being the first person photographed gesturing the middle finger. In 1886, an image was captured of him "flipping off" a member of the New York Giants in a team photo.[15]

See also

[edit]- 300 win club

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career WHIP leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual shutout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball no-hitters

References

[edit]- ^ Achorn 2010, p. 19

- ^ McKenna, Brian. "Old Hoss Radbourn". The Society for American Baseball Research Biography Project. The Society for American Baseball Research. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Achorn 2010, p. 22

- ^ Kahn, pp. 55–62

- ^ "Old Hoss Radbourn Stats". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Under modern rules, a team that is unable to field nine players would have to forfeit the game, but a substitution would be allowed.

- ^ "1883 Providence Grays – Statmaster Pitching Results". Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ Kahn, pp. 68–70

- ^ Jazayerli, Rany (March 2, 2004). "A Brief History of Pitcher Usage". Baseball Prospectus Basics. Baseball Prospectus. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ "1884 World Series - Providence Grays over New York Metropolitans (3-0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Radbourn, Charles". National Baseball Hall of Fame Museum.

- ^ a b Yoo, Sarah (2008). Candace Summers (ed.). "Radbourn, Charles 'Old Hoss'". McLean County Museum of History.

- ^ Quinion, Michael (2011). "Charley horse". World Wide Words. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ "Meaning and origin of the term 'charley horse'". April 3, 2017.

- ^ Achorn, Edward (2010). Fifty-Nine in '84: Old Hoss Radbourn, Barehanded Baseball, and the Greatest Season a Pitcher Ever Had. Smithsonian Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-06-182586-6.

- Achorn, Edward (2010). Fifty-nine in '84: Old Hoss Radbourn, Barehanded Baseball, and the Greatest Season a Pitcher Ever Had. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-0-06-182586-6.

- Kahn, Roger (2000). The Head Game. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-100441-2.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch