Culberson County, Texas

Culberson County | |

|---|---|

Culberson County Courthouse in Van Horn | |

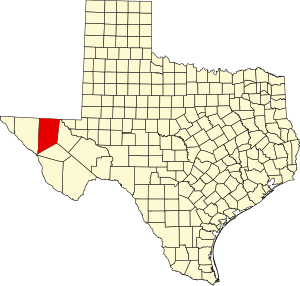

Location within the U.S. state of Texas | |

Texas's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 31°27′N 104°31′W / 31.45°N 104.52°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1912 |

| Named for | David B. Culberson |

| Seat | Van Horn |

| Largest town | Van Horn |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,813 sq mi (9,880 km2) |

| • Land | 3,813 sq mi (9,880 km2) |

| • Water | 0.2 sq mi (0.5 km2) 0.01% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 2,188 |

| • Estimate (2022) | 2,155 |

| • Density | 0.6/sq mi (0.2/km2) |

| Time zones | |

| most of county | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| northwestern | UTC−7 (Mountain) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| Congressional district | 23rd |

| Website | www |

Culberson County is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2020 census, its population was 2,188.[1] The county seat is Van Horn.[2] Culberson County was founded in 1911 and organized the next year.[3] It is named for David B. Culberson, a Confederate soldier and U.S. representative.

Culberson County is primarily in the Central Time Zone, but northwestern Culberson County, including Guadalupe Mountains National Park, is in the Mountain Time Zone, making it one of only a few U.S. counties officially split into two time zones. It is one of the nine counties that comprise the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas.

History

[edit]

Native Americans

[edit]Prehistoric Clovis culture peoples[4] in Culberson County lived in the rock shelters and caves nestled near water supplies. These people left behind artifacts and pictographs as evidence of their presence.[5] With its treacherous topography, the area remained untouched by white explorations for centuries.

Jumano Indians led the Antonio de Espejo[6] 1582-1583 expedition near Toyah Lake on a better route to the farming and trade area of La Junta de los Ríos. Espejo's diary places the Jumano along the Pecos River and its tributaries.[7]

Antonio de Espejo was also the first white person to see the Mescalero Apache just east of the Guadalupe Mountains. The Mescalero [8] frequented the area to irrigate their crops. In 1849, John Salmon "Rip" Ford[9] explored the area between San Antonio and El Paso, noting in his mapped report the productive land upon which the Mescalero Indians farmed. By the mid-17th century, the Mescaleros expanded their territory to the Plains Navajos and Pueblos from the Guadalupes, and El Paso del Norte. Their feared presence in the area deterred white settlers. In January 1870, a group of soldiers attacked a Mescalero Apache village near Delaware Creek in the Guadalupe Mountains. In July 1880, soldiers at Tinaja de las Palmas attacked a group of Mescaleros led by Chief Victorio.[10] August 1880, buffalo soldiers ambushed Victorio at Rattlesnake Springs. Victorio retreated to Mexico and was killed in October by Mexican soldiers.[11]

Explorations

[edit]The demand for new routes from Texas to California caused an uptick in explorations.[12] The San Antonio-to-El Paso leg of the San Antonio-California Trail was surveyed in 1848 under the direction of John Coffee Hays.

Texas Commissioner Robert Simpson Neighbors[13] was sent by Governor Peter Hansborough Bell in 1850 to organize El Paso.

Lt. Francis Theodore Bryan[14] camped at Guadalupe Pass while exploring a route from San Antonio to El Paso via Fredericksburg. Upon reaching El Paso in July 1849, his report recommended sink wells along the route. In July 1848, Secretary of War William L. Marcy wanted a military post established on the north side of the Rio Grande. Major Jefferson Van Horne[15] was sent out in 1849 to establish Marcy's goal.

John Russell Bartlett,[16][17] was commissioned in 1850 to carry out the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Bartlett declared the Guadalupe Mountains dark and gloomy, and proposed a transcontinental railroad be built south of the peaks. Three years later, Captain John Pope[18] was sent to scout out a railroad route, and in the succeeding year to search for artesian water supplies.

The San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line and the Butterfield Overland Mail[19] both serviced the area 1857–1861. These mail coaches provided a means for travelers to reach California in 27 days if the passenger had the $200 for a one-way fare and was courageous enough to withstand the weather and dangers en route.[20]

Rival railway companies began competing for rights of way. The Texas and Pacific Railway[21] and the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway[22] eventually reached an agreement to share the tracks.

County established and growth

[edit]

Culberson County was established in 1911 from El Paso County and named after David B. Culberson.[23] The county was organized in 1912. Van Horn became the county seat.[24]

With the opening of the railways, ranchers began to settle in the county. Lobo was settled in part due to misrepresentation by promoters. A class-action lawsuit by the residents forced the promoters to build the Lobo Hotel. Unfortunately, the area was struck by two powerful earthquakes[25] - one in 1929, and the 6.0 quake near Valentine that was felt as far away as Dallas. The hotel was destroyed.[26]

Guadalupe Mountains National Park[27][28] was established in 1972. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1966 legislation to create the park. Stipulation was made that all mineral, oil, and gas rights had to be ceded to the federal government.

Space exploration

[edit]Blue Origin, the space vehicle development company founded by Jeff Bezos, maintains a suborbital launch site about 25 miles north of Van Horn, Texas.

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 3,813 square miles (9,880 km2), of which 3,813 square miles (9,880 km2) are land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) (0.01%) is covered by water.[29] It is the fifth-largest county by area in Texas. The largest part of Guadalupe Mountains National Park lies in the northwestern corner of the county, including McKittrick Canyon and Guadalupe Peak, the highest natural point in Texas at 8,751 ft (2,667 m).

Major highways

[edit]

Adjacent counties

[edit]- Eddy County, New Mexico (north)

- Reeves County (east)

- Jeff Davis County (south)

- Hudspeth County (west)

- Otero County, New Mexico (northwest)

National protected areas

[edit]Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 912 | — | |

| 1930 | 1,228 | 34.6% | |

| 1940 | 1,653 | 34.6% | |

| 1950 | 1,825 | 10.4% | |

| 1960 | 2,794 | 53.1% | |

| 1970 | 3,429 | 22.7% | |

| 1980 | 3,315 | −3.3% | |

| 1990 | 3,407 | 2.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,975 | −12.7% | |

| 2010 | 2,398 | −19.4% | |

| 2020 | 2,188 | −8.8% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 2,155 | [30] | −1.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] 1850–2010[32] 2010–2020[1] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[33] | Pop 2010[34] | Pop 2020[35] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 733 | 504 | 445 | 24.64% | 21.02% | 20.34% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 19 | 8 | 20 | 0.64% | 0.33% | 0.91% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 11 | 13 | 11 | 0.37% | 0.54% | 0.50% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 17 | 22 | 28 | 0.57% | 0.92% | 1.28% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Other Race alone (NH) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.14% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 46 | 24 | 36 | 1.55% | 1.00% | 1.65% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 2,149 | 1,827 | 1,645 | 72.24% | 76.19% | 75.18% |

| Total | 2,975 | 2,398 | 2,188 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 2,188 people, 668 households, and 400 families residing in the county.

As of the census[36] of 2000, 2,975 people, 1,052 households, and 797 families resided in the county. The population density was less than 1/km2 (2.6/sq mi). The 1,321 housing units were at a density less than one per square mile (0/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 68.94% White, 0.71% African American, 0.47% Native American, 0.57% Asian, 27.13% from other races, and 2.18% from two or more races. About 72.24% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

Of the 1,052 households, 39.10% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.20% were married couples living together, 13.50% had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.20% were not families. About 21.50% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.40% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.82 and the average family size was 3.30.

In the county, the population was distributed as 32.20% under the age of 18, 7.80% from 18 to 24, 25.80% from 25 to 44, 23.00% from 45 to 64, and 11.20% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.70 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.10 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $25,882, and for a family was $28,547. Males had a median income of $22,500 versus $14,817 for females. The per capita income for the county was $11,493. About 21.50% of families and 25.10% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.20% of those under age 18 and 19.40% of those age 65 or over.

Communities

[edit]Town

[edit]- Van Horn (county seat)

Unincorporated communities

[edit]Ghost towns

[edit]Education

[edit]All of the county is in the Culberson County-Allamoore Independent School District.[37]

All of the county is in the service area of Odessa College.[38]

Politics

[edit]Like most counties in heavily Hispanic South Texas, Culberson County leans Democratic. The last Republican presidential candidate to carry the county was George W. Bush in 2004, who drew even with Kerry among Hispanic voters in the state. Democratic strength has declined in the county in recent years, with Joe Biden barely receiving over 50% of the vote in 2020.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 415 | 48.03% | 438 | 50.69% | 11 | 1.27% |

| 2016 | 280 | 36.51% | 454 | 59.19% | 33 | 4.30% |

| 2012 | 295 | 33.56% | 568 | 64.62% | 16 | 1.82% |

| 2008 | 257 | 33.86% | 492 | 64.82% | 10 | 1.32% |

| 2004 | 407 | 51.65% | 375 | 47.59% | 6 | 0.76% |

| 2000 | 413 | 40.81% | 577 | 57.02% | 22 | 2.17% |

| 1996 | 329 | 26.51% | 804 | 64.79% | 108 | 8.70% |

| 1992 | 251 | 29.63% | 424 | 50.06% | 172 | 20.31% |

| 1988 | 417 | 42.46% | 557 | 56.72% | 8 | 0.81% |

| 1984 | 509 | 55.51% | 407 | 44.38% | 1 | 0.11% |

| 1980 | 541 | 55.43% | 423 | 43.34% | 12 | 1.23% |

| 1976 | 373 | 47.40% | 407 | 51.72% | 7 | 0.89% |

| 1972 | 555 | 69.12% | 238 | 29.64% | 10 | 1.25% |

| 1968 | 298 | 38.55% | 330 | 42.69% | 145 | 18.76% |

| 1964 | 314 | 39.90% | 473 | 60.10% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 300 | 46.15% | 343 | 52.77% | 7 | 1.08% |

| 1956 | 324 | 54.36% | 269 | 45.13% | 3 | 0.50% |

| 1952 | 331 | 56.78% | 252 | 43.22% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 38 | 12.42% | 244 | 79.74% | 24 | 7.84% |

| 1944 | 17 | 6.77% | 200 | 79.68% | 34 | 13.55% |

| 1940 | 45 | 12.89% | 303 | 86.82% | 1 | 0.29% |

| 1936 | 23 | 8.78% | 239 | 91.22% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1932 | 18 | 5.92% | 285 | 93.75% | 1 | 0.33% |

| 1928 | 72 | 45.86% | 85 | 54.14% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 15 | 12.82% | 93 | 79.49% | 9 | 7.69% |

| 1920 | 6 | 12.77% | 40 | 85.11% | 1 | 2.13% |

| 1916 | 2 | 1.57% | 124 | 97.64% | 1 | 0.79% |

| 1912 | 0 | 0.00% | 145 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

See also

[edit]- List of museums in West Texas

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Culberson County, Texas

- Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks in Culberson County

- Beach Mountains

References

[edit]- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Texas: Individual County Chronologies". Texas Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2008. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Mallouf, Robert J. "Exploring the Past in Trans-Pecos Texas". Sul Ross University. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas Beyond History

- ^ "Artistic Expression". Texas Beyond History. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas Beyond History

- ^ Blake, Robert Bruce: de Espejo, Antonio from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ "Who Were The Jumano?". Texas Beyond History. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas Beyond History

- ^ "Texas Indians Map". R E. Moore and Texarch Associates. Retrieved April 30, 2010. R E. Moore and Texarch Associates

- ^ Connor, Seymour V: Ford, John Salmon from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ Stout, Joseph A. "Chief Victorio". King Snake. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Davis, Stanford L. "Victorio's War". Buffalo Soldier. Archived from the original on September 21, 2007. Stanford L. Davis, M.A.

- ^ Kohout, Martin Donell: Culberson County from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ Richardson, Rupert N: Neighbors, Robert Simpson from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historic

- ^ Powell, William S: Bryan, Francis Theodore from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ Kohout, Martin Donell: Van Horne, Jefferson from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ Faulk, Odie B: Bartlett, John Russell from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ "Bartlett, John Russell". The John Russell Bartlett Society. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Cutrer, Thomas W: Pope, John from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ "San Antonio-San Diego Mail". State of California Parks Department. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "San Antonio-California Trail". Texas Historical Marker. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Texas and Pacific Railway". Texas and Pacific Railway. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway". Texas Transportation Museum. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Hooker, Anne W: Culberson, David Browning from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ "Van Horn, Texas". Texas Escapes - Blueprints For Travel, LLC. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas Escapes - Blueprints For Travel, LLC.

- ^ "Texas Earthquakes". Institute for Geophysics. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Lobo, Texas". Lobo, Texas. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Guadalupe Mountains National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Maliszkiewctz, Mark: Guadalupe Mountains National Park from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved April 30, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". Census.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Texas Almanac: Population History of Counties from 1850–2010" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Culberson County, Texas". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Culberson County, Texas". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Culberson County, Texas". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Culberson County, TX" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022. - Text list

- ^ Texas Education Code, Section 130.193, "Odessa College District Service Area".

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Culberson County Government website

- Historic Photographs of Culberson County from the Clark Hotel Museum, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Culberson County in Handbook of Texas Online at the University of Texas

- Entry for David B. Culberson, for whom Culberson County was named, from the Biographical Encyclopedia of Texas published 1880, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch