Pseudoephedrine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌsuːdoʊ.ɪˈfɛdrɪn, -ˈɛfɪdriːn/ |

| Trade names | Afrinol, Sudafed, Sinutab, others |

| Other names | PSE; PDE; (+)-ψ-Ephedrine; ψ-Ephedrine; d-Isoephedrine; (1S,2S)-Pseudoephedrine; d-Pseudoephedrine; (+)-Pseudoephedrine; L(+)-Pseudoephedrine; Isoephedrine; (1S,2S)-α,N-Dimethyl-β-hydroxyphenethylamine; (1S,2S)-N-Methyl-β-hydroxyamphetamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682619 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1][2] |

| Drug class | Norepinephrine releasing agents; Sympathomimetics; Nasal decongestants; Psychostimulants |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100%[8] |

| Protein binding | 21–29% (AGP, HSA)[9][10] |

| Metabolism | Not extensively metabolized[11][1][2] |

| Metabolites | • Norpseudoephedrine[1] |

| Onset of action | 30 minutes[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 5.4 hours (range 3–16 hours dependent on urine pH)[2][1][11] |

| Duration of action | 4–12 hours[1][12] |

| Excretion | Urine: 43–96% (unchanged)[1][11][2][8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.835 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H15NO |

| Molar mass | 165.236 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Pseudoephedrine, sold under the brand name Sudafed among others, is a sympathomimetic medication which is used as a decongestant to treat nasal congestion.[1][13][2] It has also been used off-label for certain other indications, like treatment of low blood pressure.[14][15][16] At higher doses, it may produce various additional effects, including psychostimulant,[17][1] appetite suppressant,[18] and performance-enhancing effects.[19][20] In relation to this, non-medical use of pseudoephedrine has been encountered.[17][1][18][19][20] The medication is taken by mouth.[1][2]

Side effects of pseudoephedrine include insomnia, increased heart rate, and increased blood pressure, among others.[21][2][1][22] Rarely, pseudoephedrine has been associated with serious cardiovascular complications like heart attack and hemorrhagic stroke.[18][23][15] Some people may be more sensitive to its cardiovascular effects.[22][1] Pseudoephedrine acts as a norepinephrine releasing agent, thereby indirectly activating adrenergic receptors.[24][2][25][1] As such, it is an indirectly acting sympathomimetic.[24][2][25][1] Pseudoephedrine significantly crosses into the brain, but has some peripheral selectivity due to its hydrophilicity.[25][26] Chemically, pseudoephedrine is a substituted amphetamine and is closely related to ephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, and amphetamine.[1][13][2] It is the (1S,2S)-enantiomer of β-hydroxy-N-methylamphetamine.[27]

Along with ephedrine, pseudoephedrine occurs naturally in ephedra, which has been used for thousands of years in traditional Chinese medicine.[13][28] It was first isolated from ephedra in 1889.[28][13][29] Subsequent to its synthesis in the 1920s, pseudoephedrine was introduced for medical use as a decongestant.[13] Pseudoephedrine is widely available over-the-counter in both single-drug and combination preparations.[30][22][13][2] Availability of pseudoephedrine has been restricted starting in 2005 as it can be used to synthesize methamphetamine.[13][2] Phenylephrine has replaced pseudoephedrine in many over-the-counter oral decongestant products.[2] However, oral phenylephrine appears to be ineffective as a decongestant.[31][32]

Medical uses

[edit]Nasal congestion

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2011) |

Pseudoephedrine is a sympathomimetic and is well-known for shrinking swollen nasal mucous membranes, so it is often used as a decongestant. It reduces tissue hyperemia, edema, and nasal congestion commonly associated with colds or allergies. Other beneficial effects may include increasing the drainage of sinus secretions, and opening of obstructed Eustachian tubes. The same vasoconstriction action can also result in hypertension, which is a noted side effect of pseudoephedrine.

Pseudoephedrine can be used either as oral or as topical decongestant. Due to its stimulating qualities, however, the oral preparation is more likely to cause adverse effects, including urinary retention.[33][34] According to one study, pseudoephedrine may show effectiveness as an antitussive drug (suppression of cough).[35]

Pseudoephedrine is indicated for the treatment of nasal congestion, sinus congestion, and Eustachian tube congestion.[36] Pseudoephedrine is also indicated for vasomotor rhinitis, and as an adjunct to other agents in the optimum treatment of allergic rhinitis, croup, sinusitis, otitis media, and tracheobronchitis.[36]

Other uses

[edit]Amphetamine-type stimulants and other catecholaminergic agents are known to have wakefulness-promoting effects and are used in the treatment of hypersomnia and narcolepsy.[37][38][39] Pseudoephedrine at therapeutic doses does not appear to improve or worsen daytime sleepiness, daytime fatigue, or sleep quality in people with allergic rhinitis.[1][40] Likewise, somnolence was not lower in children with the common cold treated with pseudoephedrine for nasal congestion.[41] In any case, insomnia is a known side effect of pseudoephedrine, although the incidence is low.[21] In addition, doses of pseudoephedrine above the normal therapeutic range have been reported to produce psychostimulant effects, including insomnia and reduced sense of fatigue.[17]

There has been interest in pseudoephedrine as an appetite suppressant for the treatment of obesity.[18] However, due to lack of clinical data and potential cardiovascular side effects, this use is not recommended.[18] Only a single placebo-controlled study of pseudoephedrine for weight loss exists (120 mg/day slow-release for 12 weeks) and found no significant difference in weight lost compared to placebo (-4.6 kg vs. -4.5 kg).[18][42] This was in contrast to phenylpropanolamine, which has been found to be more effective at promoting weight loss compared to placebo and has been more widely studied and used in the treatment of obesity.[43][44][42]

Pseudoephedrine has been used limitedly in the treatment of orthostatic intolerance including orthostatic hypotension[14] and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).[16][45][46] However, its effectiveness in the treatment of POTS is controversial.[16][45] Pseudoephedrine has also been used limitedly in the treatment of refractory hypotension in intensive care units.[15] However, data on this use are limited to case reports and case series.[15]

Pseudoephedrine is also used as a first-line prophylactic for recurrent priapism.[47] Erection is largely a parasympathetic response, so the sympathetic action of pseudoephedrine may serve to relieve this condition. Data for this use are however anecdotal and effectiveness has been described as variable.[47]

Treatment of urinary incontinence is an off-label use for pseudoephedrine and related medications.[48][49]

Available forms

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is available by itself over-the-counter in the form of 30 and 60 mg immediate-release and 120 and 240 mg extended-release oral tablets in the United States.[30][50][51][52]

Pseudoephedrine is also available over-the-counter and prescription-only in combination with numerous other drugs, including antihistamines (acrivastine, azatadine, brompheniramine, cetirizine, chlorpheniramine, clemastine, desloratadine, dexbrompheniramine, diphenhydramine, fexofenadine, loratadine, triprolidine), analgesics (acetaminophen, codeine, hydrocodone, ibuprofen, naproxen), cough suppressants (dextromethorphan), and expectorants (guaifenesin).[30][50]

Pseudoephedrine has been used in the form of the hydrochloride and sulfate salts and in a polistirex form.[30] The drug has been used in more than 135 over-the-counter and prescription formulations.[22] Many prescription formulations containing pseudoephedrine have been discontinued over time.[30]

Contraindications

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is contraindicated in patients with diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, severe or uncontrolled hypertension, severe coronary artery disease, prostatic hypertrophy, hyperthyroidism, closed angle glaucoma, or by pregnant women.[53] The safety and effectiveness of nasal decongestant use in children is unclear.[54]

Side effects

[edit]Common side effects with pseudoephedrine therapy may include central nervous system (CNS) stimulation, insomnia, nervousness, restlessness, excitability, dizziness, and anxiety.[18][15][55] Infrequent side effects include tachycardia or palpitations.[18] Rarely, pseudoephedrine therapy may be associated with mydriasis (dilated pupils), hallucinations, arrhythmias, hypertension, seizures, and ischemic colitis; as well as severe skin reactions known as recurrent pseudo-scarlatina, systemic contact dermatitis, and non-pigmenting fixed drug eruption.[18][56][53] Pseudoephedrine, particularly when combined with other drugs including narcotics, may also play a role in the precipitation of episodes of paranoid psychosis.[18][57] It has also been reported that pseudoephedrine, among other sympathomimetic agents, may be associated with the occurrence of hemorrhagic stroke and other cardiovascular complications.[18][23][15]

Due to its sympathomimetic effects, pseudoephedrine is a vasoconstrictor or pressor agent (increases blood pressure), a positive chronotrope (increases heart rate), and a positive inotrope (increases force of heart contractions).[18][1][22][19][20] The influence of pseudoephedrine on blood pressure at clinical doses is controversial.[1][22] A closely related sympathomimetic and decongestant, phenylpropanolamine, was withdrawn due to associations with markedly increased blood pressure and incidence of hemorrhagic stroke.[22] There has been concern that pseudoephedrine may likewise dangerously increase blood pressure and thereby increase the risk of stroke, whereas others have contended that the risks are exaggerated.[1][22] Besides hemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, coronary vasospasm, and sudden death have also rarely been reported with sympathomimetic ephedra compounds like pseudoephedrine and ephedrine.[18][15]

A 2005 meta-analysis found that pseudoephedrine at recommended doses had no meaningful effect on systolic or diastolic blood pressure in healthy individuals or people with controlled hypertension.[1][22] Systolic blood pressure was found to slightly increase by 0.99 mm Hg on average and heart rate was found to slightly increase by 2.83 bpm on average.[1][22] Conversely, there was no significant influence on diastolic blood pressure, which increased by 0.63 mg Hg.[22] In people with controlled hypertension, systolic hypertension increased by a similar degree of 1.20 mm Hg.[22] Immediate-release preparations, higher doses, being male, and shorter duration of use were all associated with greater cardiovascular effects.[22] A small subset of individuals with autonomic instability, perhaps in turn resulting in greater adrenergic receptor sensitivity, may be substantially more sensitive to the cardiovascular effects of sympathomimetics.[22] Subsequent to the 2005 meta-analysis, a 2015 systematic review and a 2018 meta-analysis found that pseudoephedrine at high doses (>170 mg) could increase heart rate and physical performance with larger effect sizes than lower doses.[19][20]

A 2007 Cochrane review assessed the side effects of short-term use of pseudoephedrine at recommended doses as a nasal decongestant.[21] It found that pseudoephedrine had a small risk of insomnia and this was the only side effect that occurred at rates significantly different from placebo.[21] Insomnia occurred at a rate of 5% and had an odds ratio (OR) of 6.18.[21] Other side effects, including headache and hypertension, occurred at rates of less than 4% and were not different from placebo.[21]

Tachyphylaxis is known to develop with prolonged use of pseudoephedrine, especially when it is re-administered at short intervals.[1][18]

There is a case report of temporary depressive symptoms upon discontinuation and withdrawal from pseudoephedrine.[18][58] The withdrawal symptoms included worsened mood and sadness, profoundly decreased energy, a worsened view of oneself, decreased concentration, psychomotor retardation, increased appetite, and increased need for sleep.[18][58]

Pseudoephedrine has psychostimulant effects at high doses and is a positive reinforcer with amphetamine-like effects in animals including rats and monkeys.[59][60][61][62] However, it is substantially less potent than methamphetamine or cocaine.[59][60][61]

Overdose

[edit]The maximum total daily dose of pseudoephedrine is 240 mg.[1] Pseudoephedrine may produce sympathomimetic and psychostimulant effects with overdose.[1] These may include sedation, apnea, impaired concentration, cyanosis, coma, circulatory collapse, insomnia, hallucinations, tremors, convulsions, headache, dizziness, anxiety, euphoria, tinnitus, blurred vision, ataxia, chest pain, tachycardia, palpitations, increased blood pressure, decreased blood pressure, thirstiness, sweating, difficulty with urination, nausea, and vomiting.[1] In children, symptoms have more often included dry mouth, pupil dilation, hot flashes, fever, and gastrointestinal dysfunction.[1] Pseudoephedrine may produce toxic effects both with use of supratherapeutic doses but also in people who are more sensitive to the effects of sympathomimetics.[1] Misuse of the drug has been reported in one case at massive doses of 3,000 to 4,500 mg (100–150 × 30-mg tablets) per day, with the doses gradually increased over time by this individual.[1][63] No fatalities due to pseudoephedrine misuse have been reported as of 2021.[17] However, death with pseudoephedrine has been reported generally.[1][13][18]

Interactions

[edit]Concomitant or recent (previous 14 days) monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) use can lead to hypertensive reactions, including hypertensive crisis, and should be avoided.[1][53] Clinical studies have found minimal or no influence of certain MAOIs like the weak non-selective MAOI linezolid and the potent selective MAO-B inhibitor selegiline (as a transdermal patch) on the pharmacokinetics of pseudoephedrine.[64][65][66][67] This is in accordance with the fact that pseudoephedrine is not metabolized by monoamine oxidase (MAO).[25][11][68] However, pseudoephedrine induces the release of norepinephrine, which MAOIs inhibit the metabolism of, and as such, MAOIs can still potentiate the effects of pseudoephedrine.[69][1][65] No significant pharmacodynamic interactions have been found with selegiline,[65][67] but linezolid potentiated blood pressure increases with pseudoephedrine.[64][66] However, this was deemed to be without clinical significance in the case of linezolid, though it was noted that some individuals may be more sensitive to the sympathomimetic effects of pseudoephedrine and related agents.[64][66] Pseudoephedrine is contraindicated with MAOIs like phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, and moclobemide due to the potential for synergistic sympathomimetic effects and hypertensive crisis.[1][18] It is also considered to be contraindicated with linezolid and selegiline as some individuals may react more sensitively to coadministration.[64][66][65][67]

Concomitant use of pseudoephedrine with other vasoconstrictors, including ergot alkaloids like ergotamine and dihydroergotamine, linezolid, oxytocin, ephedrine, phenylephrine, and bromocriptine, among others, is not recommended due to the possibility of greater increases in blood pressure and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.[1] Sympathomimetic effects and cardiovascular risks of pseudoephedrine may also be increased with digitalis glycosides, tricyclic antidepressants, appetite suppressants, and inhalational anesthetics.[1] Likewise, greater sympathomimetic effects of pseudoephedrine may occur when it is combined with other sympathomimetic agents.[18] Rare but serious cardiovascular complications have been reported with the combination of pseudoephedrine and bupropion.[13][70][71] Increase of ectopic pacemaker activity can occur when pseudoephedrine is used concomitantly with digitalis.[1] The antihypertensive effects of methyldopa, guanethidine, mecamylamine, reserpine, and veratrum alkaloids may be reduced by sympathomimetics like pseudoepehdrine.[1] Beta blockers like labetalol may reduce the effects of pseudoephedrine.[72][73]

Urinary acidifying agents like ascorbic acid and ammonium chloride can increase the excretion of and thereby reduce exposure to amphetamines including pseudoephedrine, whereas urinary alkalinizing agents including antacids like sodium bicarbonate as well as acetazolamide can reduce the excretion of these agents and thereby increase exposure to them.[1][11][74]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is a sympathomimetic agent which acts primarily or exclusively by inducing the release of norepinephrine.[75][25][2][24] Hence, it is an indirectly acting sympathomimetic.[75][25][2] Some sources state that pseudoephedrine has a mixed mechanism of action consisting of both indirect and direct effects by binding to and acting as an agonist of adrenergic receptors.[1][15] However, the affinity of pseudoephedrine for adrenergic receptors is described as very low or negligible.[75] Animal studies suggest that the sympathomimetic effects of pseudoephedrine are exclusively due to norepinephrine release.[76][77]

| Compound | NE | DA | 5-HT | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dextroamphetamine (S(+)-amphetamine) | 6.6–7.2 | 5.8–24.8 | 698–1765 | [80][81] | ||

| S(–)-Cathinone | 12.4 | 18.5 | 2366 | [24] | ||

| Ephedrine ((–)-ephedrine) | 43.1–72.4 | 236–1350 | >10000 | [80] | ||

| (+)-Ephedrine | 218 | 2104 | >10000 | [80][24] | ||

| Dextromethamphetamine (S(+)-methamphetamine) | 12.3–13.8 | 8.5–24.5 | 736–1291.7 | [80][82] | ||

| Levomethamphetamine (R(–)-methamphetamine) | 28.5 | 416 | 4640 | [80] | ||

| (+)-Phenylpropanolamine ((+)-norephedrine) | 42.1 | 302 | >10000 | [24] | ||

| (–)-Phenylpropanolamine ((–)-norephedrine) | 137 | 1371 | >10000 | [24] | ||

| Cathine ((+)-norpseudoephedrine) | 15.0 | 68.3 | >10000 | [24] | ||

| (–)-Norpseudoephedrine | 30.1 | 294 | >10000 | [24] | ||

| (–)-Pseudoephedrine | 4092 | 9125 | >10000 | [24] | ||

| Pseudoephedrine ((+)-pseudoephedrine) | 224 | 1988 | >10000 | [24] | ||

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more strongly the substance releases the neurotransmitter. See also Monoamine releasing agent § Activity profiles for a larger table with more compounds. | ||||||

Pseudoephedrine induces monoamine release in vitro with an EC50 of 224 nM for norepinephrine and 1,988 nM for dopamine, whereas it is inactive for serotonin.[24][83][79] As such, it is about 9-fold selective for induction of norepinephrine release over dopamine release.[24][83][79] The drug has negligible agonistic activity at the α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors (Kact >10,000 nM).[24] At the β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors, it acts as a partial agonist with relatively low affinity (β1 = Kact = 309 μM, IA = 53%; β2 = 10 μM; IA = 47%).[84] It was an antagonist or very weak partial agonist of the β3-adrenergic receptor (Kact = ND; IA = 7%).[84] It is about 30,000 to 40,000 times less potent as a β-adrenergic receptor agonist than (–)-isoproterenol.[84]

Pseudoephedrine's principal mechanism of action relies on its action on the adrenergic system.[85][86] The vasoconstriction that pseudoephedrine produces is believed to be principally an α-adrenergic receptor response.[87] Pseudoephedrine acts on α- and β2-adrenergic receptors, to cause vasoconstriction and relaxation of smooth muscle in the bronchi, respectively.[85][86] α-Adrenergic receptors are located on the muscles lining the walls of blood vessels. When these receptors are activated, the muscles contract, causing the blood vessels to constrict (vasoconstriction). The constricted blood vessels now allow less fluid to leave the blood vessels and enter the nose, throat, and sinus linings, which results in decreased inflammation of nasal membranes, as well as decreased mucus production. Thus, by constriction of blood vessels, mainly those located in the nasal passages, pseudoephedrine causes a decrease in the symptoms of nasal congestion.[2] Activation of β2-adrenergic receptors produces relaxation of smooth muscle of the bronchi,[85] causing bronchial dilation and in turn decreasing congestion (although not fluid) and difficulty breathing.

Pseudoephedrine is less potent as a sympathomimetic and psychostimulant than ephedrine.[1][55] Clinical studies have found that pseudoephedrine is about 3.5- to 4-fold less potent than ephedrine as a sympathomimetic agent in terms of blood pressure increases and 3.5- to 7.2-fold or more less potent as a bronchodilator.[55] Pseudoephedrine is also said to have much less central effect than ephedrine and to be only a weak psychostimulant.[25][55][2][75][62] Blood vessels in the nose are around five times more sensitive than the heart to the actions of circulating epinephrine (adrenaline), which may help to explain how pseudoephedrine at the low doses used in over-the-counter products can produce nasal decongestion with minimal effects on the heart.[2] Compared to dextroamphetamine, pseudoephedrine is about 30 to 35 times less potent as a norepinephrine releasing agent and 80 to 350 times less potent as a dopamine releasing agent in vitro.[24][80][81]

Pseudoephedrine is a very weak reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase (MAO) in vitro, including both MAO-A and MAO-B (Ki = 1,000–5,800 μM).[88] It is far less potent in this action than other agents like dextroamphetamine and moclobemide.[88]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Absorption

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is orally active and is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.[1][2] Its oral bioavailability is approximately 100%.[8] The drug reaches peak concentrations after 1 to 4 hours (mean 1.9 hours) in the case of the immediate-release formulation and after 2 to 6 hours in the case of the extended-release formulation.[1][2] The onset of action of pseudoephedrine is 30 minutes.[1]

Distribution

[edit]Pseudoephedrine, due to its lack of polar phenolic groups, is relatively lipophilic.[11] This is a property it shares with related sympathomimetic and decongestant agents like ephedrine and phenylpropanolamine.[11] These agents are widely distributed throughout the body and cross the blood–brain barrier.[11] However, it is said that pseudoephedrine and phenylpropanolamine cross the blood–brain barrier only to some extent and that pseudoephedrine has limited central nervous system activity, suggesting that it is partially peripherally selective.[25][26] The blood–brain barrier permeability of pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine is reduced compared to other amphetamines due to the presence of a hydroxyl group at the β carbon which decreases their lipophilicity.[26] As such, they have a greater ratio of peripheral cardiovascular to central psychostimulant effect.[26] Besides entering the brain, these substances also cross the placenta and enter breast milk.[11]

The plasma protein binding of pseudoephedrine has been reported to be approximately 21 to 29%.[9][10] It is bound to α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) and albumin (HSA).[9][10]

Metabolism

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is not extensively metabolized and is subjected to minimal first-pass metabolism with oral administration.[11][1][2] Due to its methyl group at the α carbon (i.e., it is an amphetamine), pseudoephedrine is not a substrate for monoamine oxidase (MAO) and is not metabolized by this enzyme.[25][11][68][69] It is also not metabolized by catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT).[25] Pseudoephedrine is demethylated into the metabolite norpseudoephedrine to a small extent.[1][11] Similarly to pseudoephedrine, this metabolite is active and shows amphetamine-like effects.[11] Approximately 1 to 6% of pseudoephedrine is metabolized in the liver via N-demethylation to form norpseudoephedrine.[1]

Elimination

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is excreted primarily via the kidneys in urine.[1][11] Its urinary excretion is highly influenced by urinary pH and is decreased when the urine is acidic and is increased when it is alkaline.[1][11][55]

The elimination half-life of pseudoephedrine on average is 5.4 hours[2] and ranges from 3 to 16 hours depending on urinary pH.[1][11] At a pH of 5.6 to 6.0, the elimination half-life of pseudoephedrine was 5.2 to 8.0 hours.[11] In one study, a more acidic pH of 5.0 resulted in a half-life of 3.0 to 6.4 hours, whereas a more alkaline pH of 8.0 resulted in a half-life of 9.2 to 16.0 hours.[11] Substances that influence urinary acidity and are known to affect the excretion of amphetamine derivatives include urinary acidifying agents like ascorbic acid and ammonium chloride as well as urinary alkalinizing agents like acetazolamide.[74]

A majority of an oral dose of pseudoephedrine is excreted unchanged in urine within 24 hours of administration.[11] This has been found to range from 43 to 96%.[1][11][2] The amount excreted unchanged is dependent on urinary pH similarly to the drug's half-life, as a longer half-life and duration in the body allows more time for the drug to be metabolized.[11]

The duration of action of pseudoephedrine, which is dependent on its elimination, is 4 to 12 hours.[1][12]

Pseudoephedrine has been reported to accumulate in people with renal impairment.[89][90][91]

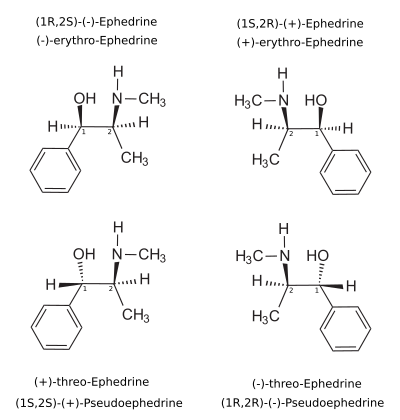

Chemistry

[edit]Pseudoephedrine, also known structurally as (1S,2S)-α,N-dimethyl-β-hydroxyphenethylamine or as (1S,2S)-N-methyl-β-hydroxyamphetamine, is a substituted phenethylamine, amphetamine, and β-hydroxyamphetamine derivative.[1][13][2] It is a diastereomer of ephedrine.[28]

Pseudoephedrine is a small-molecule compound with the molecular formula C10H15NO and a molecular weight of 165.23 g/mol.[27][92] It has an experimental log P of 0.89, while its predicted log P values range from 0.9 to 1.32.[27][92][93] The compound is relatively lipophilic,[11] but is also more hydrophilic than other amphetamines.[26] The lipophilicity of amphetamines is closely related to their brain permeability.[94] For comparison to pseudoephedrine, the experimental log P of methamphetamine is 2.1,[95] of amphetamine is 1.8,[96][95] of ephedrine is 1.1,[97] of phenylpropanolamine is 0.7,[98] of phenylephrine is -0.3,[99] and of norepinephrine is -1.2.[100] Methamphetamine has high brain permeability,[95] whereas phenylephrine and norepinephrine are peripherally selective drugs.[2][101] The optimal log P for brain permeation and central activity is about 2.1 (range 1.5–2.7).[102]

Pseudoephedrine is readily reduced into methamphetamine or oxidized into methcathinone.[1]

Nomenclatures

[edit]The dextrorotary (+)- or d- enantiomer is (1S,2S)-pseudoephedrine, whereas the levorotating (−)- or l- form is (1R,2R)-pseudoephedrine.

In the outdated D/L system (+)-pseudoephedrine is also referred to as L-pseudoephedrine and (−)-pseudoephedrine as D-pseudoephedrine (in the Fisher projection then the phenyl ring is drawn at bottom).[103][104]

Often the D/L system (with small caps) and the d/l system (with lower-case) are confused. The result is that the dextrorotary d-pseudoephedrine is wrongly named D-pseudoephedrine and the levorotary l-ephedrine (the diastereomer) wrongly L-ephedrine.

The IUPAC names of the two enantiomers are (1S,2S)- respectively (1R,2R)-2-methylamino-1-phenylpropan-1-ol. Synonyms for both are psi-ephedrine and threo-ephedrine.

Pseudoephedrine is the INN of the (+)-form, when used as pharmaceutical substance.[105]

Detection in body fluids

[edit]Pseudoephedrine may be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine to monitor any possible performance-enhancing use by athletes, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Some commercial immunoassay screening tests directed at the amphetamines cross-react appreciably with pseudoephedrine, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish pseudoephedrine from other phenethylamine derivatives. Blood or plasma pseudoephedrine concentrations are typically in the 50 to 300 μg/L range in persons taking the drug therapeutically, 500 to 3,000 μg/L in people with substance use disorder involving pseudoephedrine or poisoned patients, and 10 to 70 mg/L in cases of acute fatal overdose.[106][107]

Manufacturing

[edit]Although pseudoephedrine occurs naturally as an alkaloid in certain plant species (for example, as a constituent of extracts from the Ephedra species, also known as ma huang, in which it occurs together with other isomers of ephedrine), the majority of pseudoephedrine produced for commercial use is derived from yeast fermentation of dextrose in the presence of benzaldehyde. In this process, specialized strains of yeast (typically a variety of Candida utilis or Saccharomyces cerevisiae) are added to large vats containing water, dextrose and the enzyme pyruvate decarboxylase (such as found in beets and other plants). After the yeast has begun fermenting the dextrose, the benzaldehyde is added to the vats, and in this environment the yeast converts the ingredients to the precursor l-phenylacetylcarbinol (L-PAC). L-PAC is then chemically converted to pseudoephedrine via reductive amination.[108]

The bulk of pseudoephedrine is produced by commercial pharmaceutical manufacturers in India and China, where economic and industrial conditions favor its mass production for export.[109]

History

[edit]Pseudoephedrine, along with ephedrine, occurs naturally in ephedra.[13][28][110] This herb has been used for thousands of years in traditional Chinese medicine.[13][28][110] Pseudoephedrine was first isolated and characterized in 1889 by the German chemists Ladenburg and Oelschlägel, who used a sample that had been isolated from Ephedra vulgaris by the Merck pharmaceutical corporation of Darmstadt, Germany.[28][29][111] It was first synthesized in the 1920s in Japan.[13] Subsequently, pseudoephedrine was introduced for medical use as a decongestant.[13]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is the generic name of the drug and its INN and BAN, while pseudoéphédrine is its DCF and pseudoefedrina is its DCIT.[112][113][114][115] Pseudoephedrine hydrochloride is its USAN and BANM in the case of the hydrochloride salt; pseudoephedrine sulfate is its USAN in the case of the sulfate salt; pseudoephedrine polistirex its USAN in the case of the polistirex form; and d-isoephedrine sulfate is its JAN in the case of the sulfate salt.[112][113][114][115] Pseudoephedrine is also known as Ψ-ephedrine and isoephedrine.[112][114]

Brand names

[edit]The inclusion or exclusion of items from this list or length of this list is disputed. |

The following is a list of consumer medicines that either contain pseudoephedrine or have switched to a less-regulated alternative such as phenylephrine.

- Actifed (made by GlaxoSmithKline) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine and 2.5 mg triprolidine in certain countries.

- Advil Cold & Sinus (made by Pfizer Canada Inc.) — contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and 200 mg ibuprofen.

- Aleve-D Sinus & Cold (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains 120 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 220 mg naproxen).

- Allegra-D (made by Sanofi Aventis) — contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 60 mg of fexofenadine).

- Allerclear-D (made by Kirkland Signature) — contains 240 mg of pseudoephedrine sulfate (also 10 mg of loratadine).

- Benadryl Allergy Relief Plus Decongestant (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Kenvue company) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 8 mg acrivastine)[116]

- Cirrus (made by UCB) — contains 120 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 5 mg cetirizine).

- Claritin-D (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine sulfate (also 5 mg of loratadine).

- Claritin-D 24 Hour (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains 240 mg of pseudoephedrine sulfate (also 10 mg of loratadine).

- Codral (made by Asia-Pacific subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) — Codral Original contains pseudoephedrine, Codral New Formula substitutes phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine.

- Congestal (made by SIGMA Pharmaceutical Industries) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 650 mg paracetamol and 4 mg chlorpheniramine).[117][118]

- Contac (made by GlaxoSmithKline) — previously contained pseudoephedrine, now contains phenylephrine. As at Nov 2014 UK version still contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride per tablet.

- Demazin (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains pseudoephedrine sulfate and chlorpheniramine maleate

- Eltor (made by Sanofi Aventis) — contains pseudoephedrine hydrochloride.

- Mucinex D (made by Reckitt Benckiser) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 1200 mg guaifenesin).

- Nexafed (made by Acura Pharmaceuticals) — contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine per tablet, formulated with Impede Meth-Deterrent technology.

- Nurofen Cold & Flu (made by Reckitt Benckiser) — contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 200 mg ibuprofen).

- Respidina – contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine in the form of extended release tablets.

- Rhinex Flash (made by Pharma Product Manufacturing, Cambodia) — contains pseudoephedrine combined with paracetamol and triprolidine.

- Rhinos SR (made by Dexa Medica) — contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride

- Sinutab (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Kenvue Company) — contains 500 mg paracetamol and 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride.

- Sudafed Decongestant (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Kenvue company) — contains 60 mg of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride. Not to be confused with Sudafed PE, which contains phenylephrine.

- Theraflu (made by Novartis) — previously contained pseudoephedrine, now contains phenylephrine

- Trima — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride

- Tylol Hot (made by NOBEL İLAÇ SANAYİİ VE TİCARET A.Ş., Turkey) — a packet of 20 g contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride, 500 mg paracetamol and 4 mg chlorpheniramine maleate

- Unifed (made by United Pharmaceutical Manufacturer, Jordan) — contains pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also triprolidine and guaifenesin).

- Zyrtec-D 12 Hour (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Kenvue company) — contains 120 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 5 mg of cetirizine).

- Zephrex-D (made by Westport Pharmaceuticals) – a special meth-resistant form of pseudoephedrine that becomes gooey when heated.

Recreational use

[edit]Over-the-counter pseudoephedrine has been misused as a psychostimulant.[17] Six case reports and one case series of pseudoephedrine misuse have been published as of 2021.[17] There is a case report of self-medication with pseudoephedrine in massive doses for treatment of depression.[17][63]

Use in exercise and sports

[edit]Pseudoephedrine has been used as a performance-enhancing drug in exercise and sports due to its sympathomimetic and stimulant effects.[19][20] Because of these effects, pseudoephedrine can increase heart rate, elevate blood pressure, improve mental energy, and reduce fatigue, among other performance-enhancing effects.[19][20][22]

A 2015 systematic review found that pseudoephedrine lacked performance-enhancing effects at therapeutic doses (60–120 mg) but significantly enhanced athletic performance at supratherapeutic doses (≥180 mg).[19] A subsequent 2018 meta-analysis, which included seven additional studies, found that pseudoephedrine had a small positive effect on heart rate (SMD = 0.43) but insignificant effects on time trials, perceived exertion ratings, blood glucose levels, and blood lactate levels.[20] However, subgroup analyses revealed that effect sizes were larger for heart rate increases and quicker time trials in well-trained athletes and younger participants, for shorter exercise sessions with pseudoephedrine administered within 90 minutes beforehand, and with higher doses of pseudoephedrine.[20] A dose–response relationship was established, with larger doses (>170 mg) showing greater increases in heart rate and faster time trials than with smaller doses (≤170 mg) (SMD = 0.85 for heart rate and SMD = -0.24 for time trials, respectively).[20] In any case, the meta-analysis concluded that the performance-enhancing effects of pseudoephedrine were marginal to small and likely to be lower in magnitude than with caffeine.[20] It is relevant in this regard that caffeine is a permitted stimulant in competitive sports.[20]

Pseudoephedrine was on the International Olympic Committee's (IOC) banned substances list until 2004, when the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) list replaced the IOC list. Although WADA initially only monitored pseudoephedrine, it went back onto the "banned" list on 1 January 2010.[119]

Pseudoephedrine is excreted through urine, and concentration in urine of this drug shows a large inter-individual spread; that is, the same dose can give a vast difference in urine concentration for different individuals.[120] Pseudoephedrine is approved to be taken up to 240 mg per day. In seven healthy male subjects this dose yielded a urine concentration range of 62.8 to 294.4 microgram per milliliter (μg/mL) with mean ± standard deviation 149 ± 72 μg/mL.[121] Thus, normal dosage of 240 mg pseudoephedrine per day can result in urine concentration levels exceeding the limit of 150 μg/mL set by WADA for about half of all users.[122] Furthermore, hydration status does not affect urinary concentration of pseudoephedrine.[123]

List of doping cases

[edit]- Canadian rower Silken Laumann was stripped of her 1995 Pan American Games team gold medal after testing positive for pseudoephedrine.[124]

- In February 2000, Elena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze won gold at the 2000 European Figure Skating Championships but were stripped of their medals after Berezhnaya tested positive. This resulted in a three-month disqualification from the date of the test, and the medal being stripped.[125] She stated that she had taken cold medication approved by a doctor but had failed to inform the ISU as required.[126] The pair missed the World Championships that year as a result of the disqualification.

- Romanian gymnast Andreea Răducan was stripped of her gold medal at the 2000 Summer Olympic Games after testing positive. She took two pills given to her by the team coach for a cold. Although she was stripped of the overall gold medal, she kept her other medals, and, unlike in most other doping cases, was not banned from competing again; only the team doctor was banned for a number of years. Ion Țiriac, the president of the Romanian Olympic Committee, resigned over the scandal.[127][128]

- In the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, the IOC issued a reprimand against the Slovak ice hockey player Lubomir Visnovsky for usage of pseudoephedrine.[129]

- In the 2014 Winter Olympic Games Team Sweden and Washington Capitals ice hockey player Nicklas Bäckström was prevented from playing in the final for usage of pseudoephedrine. Bäckström claimed he was using it as allergy medication.[130] In March 2014, the IOC Disciplinary Commission decided that Bäckström would be awarded the silver medal.[131] In January 2015 Bäckström, the IOC, WADA and the IIHF agreed to a settlement in which he accepted a reprimand but was cleared of attempting to enhance his performance.[132]

Manufacture of amphetamines

[edit]Its membership in the amphetamine class has made pseudoephedrine a sought-after chemical precursor in the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine and methcathinone.[1] As a result of the increasing regulatory restrictions on the sale and distribution of pseudoephedrine, pharmaceutical firms have reformulated medications to use alternative compounds, particularly phenylephrine, even though its efficacy as an oral decongestant has been demonstrated to be indistinguishable from placebo.[133]

In the United States, federal laws control the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products.[134][135][136] Retailers in the US have created corporate policies restricting the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products.[137][138] Their policies restrict sales by limiting purchase quantities and requiring a minimum age and government issued photographic identification.[135][136] These requirements are similar to and sometimes more stringent than existing law. Internationally, pseudoephedrine is listed as a Table I precursor under the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.[139]

Legal status

[edit]Australia

[edit]

Illicit diversion of pseudoephedrine in Australia has caused significant changes to the way the products are regulated. As of 2006[update], all products containing pseudoephedrine have been rescheduled as either "Pharmacist Only Medicines" (Schedule 3) or "Prescription Only Medicines" (Schedule 4), depending on the amount of pseudoephedrine in the product. A Pharmacist Only Medicine may only be sold to the public if a pharmacist is directly involved in the transaction. These medicines must be kept behind the counter, away from public access.

Pharmacists are also encouraged (and in some states required) to log purchases with the online database Project STOP.[140]

As a result, some pharmacies no longer stock Sudafed, the common brand of pseudoephedrine cold/sinus tablets, opting instead to sell Sudafed PE, a phenylephrine product that has not been proven effective in clinical trials.[133][141][2]

Belgium

[edit]Several formulations of pseudoephedrine are available over-the-counter in Belgium.[142]

Canada

[edit]Health Canada has investigated the risks and benefits of pseudoephedrine and ephedrine/Ephedra. Near the end of the study, Health Canada issued a warning on their website stating that those who are under the age of 12, or who have heart disease and may have strokes, should avoid taking pseudoephedrine and ephedrine. Also, they warned that everyone should avoid taking ephedrine or pseudoephrine with other stimulants like caffeine. They also banned all products that contain both ephedrine (or pseudoephedrine) and caffeine.[143]

Products whose only medicinal ingredient is pseudoephedrine must be kept behind the pharmacy counter. Products containing pseudoephedrine along with other medicinal ingredients may be displayed on store shelves but may be sold only in a pharmacy when a pharmacist is present.[144][145]

Colombia

[edit]The Colombian government prohibited the trade of pseudoephedrine in 2010.[146]

Estonia

[edit]Pseudoephedrine is an over-the-counter drug in Estonia.[147]

Finland

[edit]Pseudoephedrine medicines can only be obtained with a prescription in Finland.[148][failed verification]

Japan

[edit]Medications that contain more than 10% pseudoephedrine are prohibited under the Stimulants Control Law in Japan.[149]

Mexico

[edit]On 23 November 2007, the use and trade of pseudoephedrine in Mexico was made illegal as it was argued that it was extremely popular as a precursor in the synthesis of methamphetamine.[150]

Netherlands

[edit]Pseudoephedrine was withdrawn from sale in 1989 due to concerns about adverse cardiac side effects.[151]

New Zealand

[edit]Since April 2024, pseudoephedrine has been classified as a restricted (pharmacist-only) drug in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 which allows the purchase of medicines containing pseudoephedrine from a pharmacist without a prescription.[152]

Pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and any product containing these substances, e.g. cold and flu medicines, were first classified in October 2004 as Class C Part III (partially exempted) controlled drugs, due to being the principal ingredient in methamphetamine.[153] New Zealand Customs and police officers continued to make large interceptions of precursor substances believed to be destined for methamphetamine production. On 9 October 2009, Prime Minister John Key announced pseudoephedrine-based cold and flu tablets would become prescription-only drugs and reclassified as a class B2 drug.[154] The law was amended by The Misuse of Drugs Amendment Bill 2010, which passed in August 2011.[155]

On 24 November 2023, the recently-formed National-led coalition government announced that the sale of cold medication containing pseudoephedrine would be allowed (as part of the coalition agreement between the National and ACT parties).[156]

Turkey

[edit]In Turkey, medications containing pseudoephedrine are available with prescription only.[157]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the UK, pseudoephedrine is available over the counter under the supervision of a qualified pharmacist, or on prescription. In 2007, the MHRA reacted to concerns over diversion of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine for the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine by introducing voluntary restrictions limiting over the counter sales to one box containing no more than 720 mg of pseudoephedrine in total per transaction. These restrictions became law in April 2008.[158] No form of ID is required.

United States

[edit]Federal

[edit]The United States Congress has recognized that pseudoephedrine is used in the illegal manufacture of methamphetamine. In 2005, the Committee on Education and the Workforce heard testimony concerning education programs and state legislation designed to curb this illegal practice.[citation needed]

Attempts to control the sale of the drug date back to 1986, when federal officials at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) first drafted legislation, later proposed by Senator Bob Dole, that would have placed a number of chemicals used in the manufacture of illicit drugs under the Controlled Substances Act. The bill would have required each transaction involving pseudoephedrine to be reported to the government, and federal approval of all imports and exports. Fearing this would limit legitimate use of the drug, lobbyists from over the counter drug manufacturing associations sought to stop this legislation from moving forward, and were successful in exempting from the regulations all chemicals that had been turned into a legal final product, such as Sudafed.[159]

Prior to the passage of the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005, sales of the drug became increasingly regulated, as DEA regulators and pharmaceutical companies continued to fight for their respective positions. The DEA continued to make greater progress in their attempts to control pseudoephedrine as methamphetamine production skyrocketed, becoming a serious problem in the western United States. When purity dropped, so did the number of people in rehab and people admitted to emergency rooms with methamphetamine in their systems. This reduction in purity was usually short lived, however, as methamphetamine producers eventually found a way around the new regulations.[160]

Congress passed the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 (CMEA) as an amendment to the renewal of the USA Patriot Act.[135] Signed into law by president George W. Bush on 6 March 2006,[134] the act amended 21 U.S.C. § 830, concerning the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products. The law mandated two phases, the first needing to be implemented by 8 April 2006, and the second to be completed by 30 September 2006. The first phase dealt primarily with implementing the new buying restrictions based on amount, while the second phase encompassed the requirements of storage, employee training, and record keeping.[161] Though the law was mainly directed at pseudoephedrine products it also applies to all over-the-counter products containing ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine, their salts, optical isomers, and salts of optical isomers.[161] Pseudoephedrine was defined as a "scheduled listed chemical product" under 21 U.S.C. § 802(45(A)). The act included the following requirements for merchants ("regulated sellers") who sell such products:

- Required a retrievable record of all purchases, identifying the name and address of each party, to be kept for two years

- Required verification of proof of identity of all purchasers

- Required protection and disclosure methods in the collection of personal information

- Required reports to the Attorney General of any suspicious payments or disappearances of the regulated products

- Required training of employees with regard to the requirements of the CMEA. Retailers must self-certify as to training and compliance.

- The non-liquid dose form of regulated products may only be sold in unit dose blister packs

- Regulated products must be stored behind the counter or in a locked cabinet in such a way as to restrict public access

- Sales limits (per customer):

- Daily sales limit—must not exceed 3.6 grams of pseudoephedrine base without regard to the number of transactions

- 30-day (not monthly) sales limit—must not exceed 7.5 grams of pseudoephedrine base if sold by mail order or "mobile retail vendor"

- 30-day purchase limit—must not exceed 9 grams of pseudoephedrine base. (A misdemeanor possession offense under 21 U.S.C. § 844a for the person who buys it.)

The requirements were revised in the Methamphetamine Production Prevention Act of 2008 to require that a regulated seller of scheduled listed chemical products may not sell such a product unless the purchaser:[136]

- Presents a government issued photographic identification; and

- Signs the written logbook with their name, address, and time and date of the sale

State

[edit]Most states also have laws regulating pseudoephedrine.[162][163][164]

The states of Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii (as of May 1, 2009[update]) Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana (as of August 15, 2009[update]), Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska,[165] Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia and Wisconsin have laws requiring pharmacies to sell pseudoephedrine "behind the counter". Though the drug can be purchased without a prescription, states can limit the number of units sold and can collect personal information from purchasers.[166]

The states of Oregon and Mississippi previously required a prescription for the purchase of products containing pseudoephedrine. However as of 1 January 2022 these restrictions have been repealed.[167][168] The state of Oregon reduced the number of methamphetamine lab seizures from 448 in 2004 (the final full year before implementation of the prescription only law)[169] to a new low of 13 in 2009.[170] The decrease in meth lab incidents in Oregon occurred largely before the prescription-only law took effect, according to a NAMSDL report titled Pseudoephedrine Prescription Laws in Oregon and Mississippi.[166] The report posits that the decline in meth lab incidents in both states may be due to other factors: "Mexican traffickers may have contributed to the decline in meth labs in Mississippi and Oregon (and surrounding states) as they were able to provide ample supply of equal or greater quality meth at competitive prices". Additionally, similar decreases in meth lab incidents were seen in surrounding states, according to the report, and meth-related deaths in Oregon have dramatically risen since 2007. Some municipalities in Missouri have enacted similar ordinances, including Washington,[171] Union,[172] New Haven,[173] Cape Girardeau[174] and Ozark.[175] Certain pharmacies in Terre Haute, Indiana do so as well.[176]

Another approach to controlling the drug on the state level mandated by some state governments to control the purchases of their citizens is the use of electronic tracking systems, which require the electronic submission of specified purchaser information by all retailers who sell pseudoephedrine. Thirty-two states now require the National Precursor Log Exchange (NPLEx) to be used for every pseudoephedrine and ephedrine OTC purchase, and ten of the eleven largest pharmacy chains in the US voluntarily contribute all of their similar transactions to NPLEx. These states have seen dramatic results in reducing the number of methamphetamine laboratory seizures. Prior to implementation of the system in Tennessee in 2005, methamphetamine laboratory seizures totaled 1,497 in 2004, but were reduced to 955 in 2005, and 589 in 2009.[170] Kentucky's program was implemented statewide in 2008, and since statewide implementation, the number of laboratory seizures has significantly decreased.[170] Oklahoma initially experienced success with their tracking system after implementation in 2006, as the number of seizures dropped in that year and again in 2007. In 2008, however, seizures began rising again, and have continued to rise in 2009.[170]

NPLEx appears to be successful by requiring the real-time submission of transactions, thereby enabling the relevant laws to be enforced at the point of sale. By creating a multi-state database and the ability to compare all transactions quickly, NPLEx enables pharmacies to deny purchases that would be illegal based on gram limits, age, or even to convicted meth offenders in some states. NPLEx also enforces the federal gram limits across state lines, which was impossible with state-operated systems. Access to the records is by law enforcement agencies only, through an online secure portal.[177]

Research

[edit]Pseudoephedrine has been studied in the treatment of snoring.[178] However, data are inadequate to support this use.[178]

A study has found that pseudoephedrine can reduce milk production in breastfeeding women.[179][180] This might have been due to suppression of prolactin secretion.[180] Pseudoephedrine might be useful for lactation suppression.[179][180]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb Głowacka K, Wiela-Hojeńska A (May 2021). "Pseudoephedrine—Benefits and Risks". Int J Mol Sci. 22 (10): 5146. doi:10.3390/ijms22105146. PMC 8152226. PMID 34067981.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Eccles R (January 2007). "Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongeststant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 63 (1): 10–14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02833.x. PMC 2000711. PMID 17116124.

- ^ "Project STOP A Pharmacy Guild Initiative, May 2016" (PDF). The Pharmacy Guild of Australia. 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice No. 509, March 2016" (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. 7 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Project STOP mandatory for pharmacists in NSW from next month". Pulse.IT. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "Background on Update to NAPRA NHP Policy". napra.ca. 10 June 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker K, eds. (2006). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

- ^ a b c Volpp M, Holzgrabe U (January 2019). "Determination of plasma protein binding for sympathomimetic drugs by means of ultrafiltration". Eur J Pharm Sci. 127: 175–184. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2018.10.027. PMID 30391401.

- ^ a b c Schmidt S (2023). Lang-etablierte Arzneistoffe genauer unter die Lupe genommen: Enantioselektive Proteinbindung und Stabilitätsstudien [A closer look at long-established drugs: enantioselective protein binding and stability studies] (Thesis) (in German). Universität Würzburg. doi:10.25972/opus-34594.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Chua SS, Benrimoj SI, Triggs EJ (1989). "Pharmacokinetics of non-prescription sympathomimetic agents". Biopharm Drug Dispos. 10 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1002/bdd.2510100102. PMID 2647163.

- ^ a b Aaron CK (August 1990). "Sympathomimetics". Emerg Med Clin North Am. 8 (3): 513–526. doi:10.1016/S0733-8627(20)30256-X. PMID 2201518.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Laccourreye O, Werner A, Giroud JP, Couloigner V, Bonfils P, Bondon-Guitton E (February 2015). "Benefits, limits and danger of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine as nasal decongestants". Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 132 (1): 31–34. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2014.11.001. PMID 25532441.

- ^ a b Freeman R, Kaufmann H (2007). "Disorders of Orthostatic Tolerance—Orthostatic Hypotension, Postural Tachycardia Syndrome, and Syncope". Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 13: 50–88. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000299966.05395.6c. ISSN 1080-2371.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Van Berkel MA, Fuller LA, Alexandrov AW, Jones GM (2015). "Methylene blue, midodrine, and pseudoephedrine: a review of alternative agents for refractory hypotension in the intensive care unit". Crit Care Nurs Q. 38 (4): 345–358. doi:10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000086. PMID 26335214.

- ^ a b c Fedorowski A (April 2019). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management". J Intern Med. 285 (4): 352–366. doi:10.1111/joim.12852. PMID 30372565.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schifano F, Chiappini S, Miuli A, Mosca A, Santovito MC, Corkery JM, et al. (2021). "Focus on Over-the-Counter Drugs' Misuse: A Systematic Review on Antihistamines, Cough Medicines, and Decongestants". Front Psychiatry. 12: 657397. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.657397. PMC 8138162. PMID 34025478.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Munafò A, Frara S, Perico N, Di Mauro R, Cortinovis M, Burgaletto C, et al. (December 2021). "In search of an ideal drug for safer treatment of obesity: The false promise of pseudoephedrine". Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 22 (4): 1013–1025. doi:10.1007/s11154-021-09658-w. PMC 8724077. PMID 33945051.

- ^ a b c d e f g Trinh KV, Kim J, Ritsma A (2015). "Effect of pseudoephedrine in sport: a systematic review". BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 1 (1): e000066. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000066. PMC 5117033. PMID 27900142.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gheorghiev MD, Hosseini F, Moran J, Cooper CE (October 2018). "Effects of pseudoephedrine on parameters affecting exercise performance: a meta-analysis". Sports Med Open. 4 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/s40798-018-0159-7. PMC 6173670. PMID 30291523.

- ^ a b c d e f Taverner D, Latte J (January 2007). Latte GJ (ed.). "Nasal decongestants for the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001953. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001953.pub3. PMID 17253470.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Salerno SM, Jackson JL, Berbano EP (2005). "Effect of oral pseudoephedrine on blood pressure and heart rate: a meta-analysis". Arch Intern Med. 165 (15): 1686–1694. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.15.1686. PMID 16087815.

- ^ a b Cantu C, Arauz A, Murillo-Bonilla LM, López M, Barinagarrementeria F (July 2003). "Stroke associated with sympathomimetics contained in over-the-counter cough and cold drugs". Stroke. 34 (7): 1667–1672. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000075293.45936.FA. PMID 12791938.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rothman RB, Vu N, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Hufeisen SJ, Compton-Toth BA, et al. (October 2003). "In vitro characterization of ephedrine-related stereoisomers at biogenic amine transporters and the receptorome reveals selective actions as norepinephrine transporter substrates". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 307 (1): 138–145. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.053975. PMID 12954796.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j O'Donnell SR (March 1995). "Sympathomimetic vasoconstrictors as nasal decongestants". Med J Aust. 162 (5): 264–267. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb139882.x. PMID 7534374.

- ^ a b c d e Bouchard R, Weber AR, Geiger JD (July 2002). "Informed decision-making on sympathomimetic use in sport and health". Clin J Sport Med. 12 (4): 209–224. doi:10.1097/00042752-200207000-00003. PMID 12131054.

- ^ a b c "Pseudoephedrine". PubChem. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Abourashed EA, El-Alfy AT, Khan IA, Walker L (August 2003). "Ephedra in perspective--a current review". Phytother Res. 17 (7): 703–712. doi:10.1002/ptr.1337. PMID 12916063.

- ^ a b Chen KK, Kao CH (1926). "Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine, their Isolation, Constitution, Isomerism, Properties, Derivatives and Synthesis. (with a Bibliography) **The expense of this work has been defrayed by a part of a grant from the Committee on Therapeutic Research, Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry, American Medical Association". The Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association (1912). 15 (8): 625–639. doi:10.1002/jps.3080150804.

- ^ a b c d e "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". accessdata.fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ Hatton RC, Hendeles L (March 2022). "Why Is Oral Phenylephrine on the Market After Compelling Evidence of Its Ineffectiveness as a Decongestant?". Ann Pharmacother. 56 (11): 1275–1278. doi:10.1177/10600280221081526. PMID 35337187. S2CID 247712448.

- ^ Hendeles L, Hatton RC (July 2006). "Oral phenylephrine: an ineffective replacement for pseudoephedrine?". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 118 (1): 279–280. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.002. PMID 16815167.

- ^ "American Urological Association – Medical Student Curriculum – Urinary Incontinence". American Urological Association. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Acute urinary retention due to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride in a 3-year-old child". The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Minamizawa K, Goto H, Ohi Y, Shimada Y, Terasawa K, Haji A (September 2006). "Effect of d-pseudoephedrine on cough reflex and its mode of action in guinea pigs". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 102 (1): 136–142. doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0060526. PMID 16974066.

- ^ a b Bicopoulos D, ed. (2002). AusDI: Drug information for the healthcare professional (2nd ed.). Castle Hill: Pharmaceutical Care Information Services.

- ^ Sakai N, Chikahisa S, Nishino S (2010). "Stimulants in Excessive Daytime Sleepiness". Sleep Medicine Clinics. 5 (4): 591–607. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2010.08.009.

- ^ Takenoshita S, Nishino S (June 2020). "Pharmacologic Management of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness". Sleep Med Clin. 15 (2): 177–194. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.02.006. PMID 32386693.

- ^ Boutrel B, Koob GF (September 2004). "What keeps us awake: the neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness-promoting medications". Sleep. 27 (6): 1181–1194. doi:10.1093/sleep/27.6.1181. PMID 15532213.

- ^ Sherkat AA, Sardana N, Safaee S, Lehman EB, Craig TJ (February 2011). "The role of pseudoephedrine on daytime somnolence in patients suffering from perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR)". Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 106 (2): 97–102. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2010.11.013. PMID 21277510.

- ^ Gelotte CK, Albrecht HH, Hynson J, Gallagher V (December 2019). "A Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study of Pseudoephedrine for the Temporary Relief of Nasal Congestion in Children With the Common Cold". J Clin Pharmacol. 59 (12): 1573–1583. doi:10.1002/jcph.1472. PMC 6851811. PMID 31274197.

- ^ a b Greenway F, Herber D, Raum W, Herber D, Morales S (July 1999). "Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials with non-prescription medications for the treatment of obesity". Obes Res. 7 (4): 370–378. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00420.x. PMID 10440593.

- ^ Coulter AA, Rebello CJ, Greenway FL (July 2018). "Centrally Acting Agents for Obesity: Past, Present, and Future". Drugs. 78 (11): 1113–1132. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-0946-y. PMC 6095132. PMID 30014268.

- ^ Ioannides-Demos LL, Proietto J, McNeil JJ (2005). "Pharmacotherapy for obesity". Drugs. 65 (10): 1391–418. doi:10.2165/00003495-200565100-00006. PMID 15977970.

- ^ a b Fedorowski A, Melander O (April 2013). "Syndromes of orthostatic intolerance: a hidden danger". J Intern Med. 273 (4): 322–335. doi:10.1111/joim.12021. PMID 23216860.

- ^ Abed H, Ball PA, Wang LX (March 2012). "Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: A brief review". J Geriatr Cardiol. 9 (1): 61–67. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1263.2012.00061. PMC 3390096. PMID 22783324.

- ^ a b Muneer A, Minhas S, Arya M, Ralph DJ (August 2008). "Stuttering priapism--a review of the therapeutic options". Int J Clin Pract. 62 (8): 1265–1270. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01780.x. PMID 18479367.

- ^ Weiss BD (15 January 2005). "Selecting Medications for the Treatment of Urinary Incontinence – January 15, 2005 – American Family Physician". American Family Physician. 71 (2): 315–322. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Culligan PJ, Heit M (December 2000). "Urinary incontinence in women: evaluation and management". American Family Physician. 62 (11): 2433–44, 2447, 2452. PMID 11130230. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ a b Kizior R, Hodgson BB (2014). Saunders Nursing Drug Handbook 2015 - E-Book: Saunders Nursing Drug Handbook 2015 - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1016. ISBN 978-0-323-28018-1. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ Braun DD (2012). Over the Counter Pharmaceutical Formulations. Elsevier Science. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8155-1849-5. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ Berry TM (2001). Nursing Nonprescription Drug Handbook. Nursing Drug Handbook Series. Springhouse. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-58255-101-2. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Rossi S, ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3.

- ^ Deckx L, De Sutter AI, Guo L, Mir NA, van Driel ML (October 2016). "Nasal decongestants in monotherapy for the common cold". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (10): CD009612. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009612.pub2. PMC 6461189. PMID 27748955.

- ^ a b c d e Hughes DT, Empey DW, Land M (December 1983). "Effects of pseudoephedrine in man". J Clin Hosp Pharm. 8 (4): 315–321. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.1983.tb01053.x. PMID 6198336.

- ^ Vidal C, Prieto A, Pérez-Carral C, Armisén M (April 1998). "Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption due to pseudoephedrine". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 80 (4): 309–310. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62974-2. PMID 9564979.

- ^ "Adco-Tussend". Home.intekom.com. 15 March 1993. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b Webb J, Dubose J (2013). "Symptoms of major depression after pseudoephedrine withdrawal: a case report". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 25 (2): E54–E55. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12060138. PMID 23686066.

- ^ a b Freeman KB, Wang Z, Woolverton WL (April 2010). "Self-administration of (+)-methamphetamine and (+)-pseudoephedrine, alone and combined, by rhesus monkeys". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 95 (2): 198–202. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2010.01.005. PMC 2838499. PMID 20100506.

- ^ a b Wee S, Ordway GA, Woolverton WL (June 2004). "Reinforcing effect of pseudoephedrine isomers and the mechanism of action". Eur J Pharmacol. 493 (1–3): 117–125. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.030. PMID 15189772.

- ^ a b Tongjaroenbuangam W, Meksuriyen D, Govitrapong P, Kotchabhakdi N, Baldwin BA (February 1998). "Drug discrimination analysis of pseudoephedrine in rats". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 59 (2): 505–510. doi:10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00459-0. PMID 9477001.

- ^ a b Akiba K, Satoh S, Matsumura H, Suzuki T, Kohno H, Tadano T, et al. (May 1982). "[Effect of d-pseudoephedrine on the central nervous system in mice]". Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 79 (5): 401–408. doi:10.1254/fpj.79.401. PMID 6813205.

- ^ a b Diaz MA, Wise TN, Semchyshyn GO (September 1979). "Self-medication with pseudoephedrine in a chronically depressed patient". Am J Psychiatry. 136 (9): 1217–1218. doi:10.1176/ajp.136.9.1217. PMID 474820.

- ^ a b c d Stalker DJ, Jungbluth GL (2003). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of linezolid, a novel oxazolidinone antibacterial". Clin Pharmacokinet. 42 (13): 1129–1140. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342130-00004. PMID 14531724.

- ^ a b c d Jacob JE, Wagner ML, Sage JI (March 2003). "Safety of selegiline with cold medications". Ann Pharmacother. 37 (3): 438–441. doi:10.1345/aph.1C175. PMID 12639177.

- ^ a b c d Hendershot PE, Antal EJ, Welshman IR, Batts DH, Hopkins NK (May 2001). "Linezolid: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of coadministration with pseudoephedrine HCl, phenylpropanolamine HCl, and dextromethorpan HBr". J Clin Pharmacol. 41 (5): 563–572. doi:10.1177/00912700122010302. PMID 11361053.

- ^ a b c Azzaro AJ, VanDenBerg CM, Ziemniak J, Kemper EM, Blob LF, Campbell BJ (August 2007). "Evaluation of the potential for pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic drug interactions between selegiline transdermal system and two sympathomimetic agents (pseudoephedrine and phenylpropanolamine) in healthy volunteers". J Clin Pharmacol. 47 (8): 978–990. doi:10.1177/0091270007302950. PMID 17554106.

- ^ a b Johnson DA, Hricik JG (1993). "The pharmacology of alpha-adrenergic decongestants". Pharmacotherapy. 13 (6 Pt 2): 110S–115S, discussion 143S–146S. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1993.tb02779.x. PMID 7507588.

- ^ a b Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacol Ther. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

It is also relevant to other sympathomimetic amines contained in over-the-counter cough and cold remedies as decongestants, such as phenylpropanolamine and pseudoephedrine. Thus, MAO inhibitors potentiate the peripheral effects of indirectly acting sympathomimetic amines. It is not often realized, however, that this potentiation occurs irrespective of whether the amine is a substrate for MAO. An α-methyl group on the side chain, as in amphetamine and ephedrine, renders the amine immune to deamination so that they are not metabolized in the gut. Similarly, β-PEA would not be deaminated in the gut as it is a selective substrate for MAO-B which is not found in the gut. However, MAO inhibition in sympathetic neurones allows the cytoplasmic pool of noradrenaline to increase. It is this pool that is released by indirectly acting sympathomimetic amines and their responses are therefore potentiated irrespective of whether they are deaminated by MAO (Youdim & Finberg, 1991).

- ^ Marcucci C (2015). "Too Young to Die". A Case Approach to Perioperative Drug-Drug Interactions. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 543–545. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7495-1_120. ISBN 978-1-4614-7494-4.

- ^ Pederson KJ, Kuntz DH, Garbe GJ (May 2001). "Acute myocardial ischemia associated with ingestion of bupropion and pseudoephedrine in a 21-year-old man". Can J Cardiol. 17 (5): 599–601. PMID 11381283.

- ^ Mariani PJ (March 1986). "Pseudoephedrine-induced hypertensive emergency: treatment with labetalol". Am J Emerg Med. 4 (2): 141–142. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(86)90159-2. PMID 3947442.

- ^ a b Patrick KS, Markowitz JS (1997). "Pharmacology of methylphenidate, amphetamine enantiomers and pemoline in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 12 (6): 527–546. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1077(199711/12)12:6<527::AID-HUP932>3.0.CO;2-U. ISSN 0885-6222.

- ^ a b c d Abraham DJ (15 January 2003). Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471266949.bmc093. ISBN 978-0-471-26694-5.

- ^ Gad MZ, Azab SS, Khattab AR, Farag MA (October 2021). "Over a century since ephedrine discovery: an updated revisit to its pharmacological aspects, functionality and toxicity in comparison to its herbal extracts". Food Funct. 12 (20): 9563–9582. doi:10.1039/d1fo02093e. PMID 34533553.

- ^ Kobayashi S, Endou M, Sakuraya F, Matsuda N, Zhang XH, Azuma M, et al. (November 2003). "The sympathomimetic actions of l-ephedrine and d-pseudoephedrine: direct receptor activation or norepinephrine release?". Anesth Analg. 97 (5): 1239–1245. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000092917.96558.3C. PMID 14570629.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2003). "Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant drugs". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479 (1–3): 23–40. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.054. PMID 14612135.

- ^ a b c Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Therapeutic potential of monoamine transporter substrates". Curr Top Med Chem. 6 (17): 1845–1859. doi:10.2174/156802606778249766. PMID 17017961.

- ^ a b c d e f Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, et al. (January 2001). "Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin". Synapse. 39 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 11071707.

- ^ a b Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, et al. (2013). "Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive 'bath salts' products". Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (4): 552–562. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.204. PMC 3572453. PMID 23072836.

- ^ Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Partilla JS, Sink JR, Shulgin AT, Daley PF, et al. (April 2012). "The designer methcathinone analogs, mephedrone and methylone, are substrates for monoamine transporters in brain tissue". Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (5): 1192–203. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.304. PMC 3306880. PMID 22169943.

- ^ a b Rothman RB, Baumann MH (December 2005). "Targeted screening for biogenic amine transporters: potential applications for natural products". Life Sci. 78 (5): 512–518. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.001. PMID 16202429.

- ^ a b c Vansal SS, Feller DR (September 1999). "Direct effects of ephedrine isomers on human beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes". Biochem Pharmacol. 58 (5): 807–810. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00152-5. PMID 10449190.

- ^ a b c American Medical Association, AMA Department of Drugs (1977). AMA Drug Evaluations. PSG Publishing Co., Inc. p. 627.

- ^ a b Drug Information for the Health Care Professional. Vol. 1. Greenwood Village, Colorado.: Thomson/Micromedex. 2007. p. 2452.

- ^ Drew CD, Knight GT, Hughes DT, Bush M (September 1978). "Comparison of the effects of D-(-)-ephedrine and L-(+)-pseudoephedrine on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in man". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 6 (3): 221–225. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb04588.x. PMC 1429447. PMID 687500.

- ^ a b Ulus IH, Maher TJ, Wurtman RJ (June 2000). "Characterization of phentermine and related compounds as monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors". Biochem Pharmacol. 59 (12): 1611–1621. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00306-3. PMID 10799660.

- ^ Sequeira RP N (1998). "Central nervous system stimulants and drugs that suppress appetite". Side Effects of Drugs Annual. Vol. 21. Elsevier. p. 1–8. doi:10.1016/s0378-6080(98)80005-6. ISBN 978-0-444-82818-7.

- ^ Sica DA, Comstock TJ (October 1989). "Pseudoephedrine accumulation in renal failure". Am J Med Sci. 298 (4): 261–263. doi:10.1097/00000441-198910000-00010. PMID 2801760.

- ^ Lyon CC, Turney JH (1996). "Pseudoephedrine toxicity in renal failure". Br J Clin Pract. 50 (7): 396–397. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.1996.tb09584.x. PMID 9015914.

- ^ a b "Pseudoephedrine: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action". DrugBank Online. 1 October 1994. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Kril MB, Fung HL (May 1990). "Influence of hydrophobicity on the ion exchange selectivity coefficients for aromatic amines". J Pharm Sci. 79 (5): 440–443. doi:10.1002/jps.2600790517. PMID 2352166.

- ^ Bharate SS, Mignani S, Vishwakarma RA (December 2018). "Why Are the Majority of Active Compounds in the CNS Domain Natural Products? A Critical Analysis". J Med Chem. 61 (23): 10345–10374. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01922. PMID 29989814.

- ^ a b c Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM (August 2010). "The clinical toxicology of metamfetamine". Clin Toxicol (Phila). 48 (7): 675–694. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.516752. PMID 20849327.

Metamfetamine acts in a manner similar to amfetamine, but with the addition of the methyl group to the chemical structure. It is more lipophilic (Log p value 2.07, compared with 1.76 for amfetamine),4 thereby enabling rapid and extensive transport across the blood–brain barrier.19

- ^ "Amphetamine". PubChem. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Ephedrine". PubChem. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Norephedrine". PubChem. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Phenylephrine". PubChem. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "Norepinephrine". PubChem. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ Froese L, Dian J, Gomez A, Unger B, Zeiler FA (October 2020). "The cerebrovascular response to norepinephrine: A scoping systematic review of the animal and human literature". Pharmacol Res Perspect. 8 (5): e00655. doi:10.1002/prp2.655. PMC 7510331. PMID 32965778.

- ^ Pajouhesh H, Lenz GR (October 2005). "Medicinal chemical properties of successful central nervous system drugs". NeuroRx. 2 (4): 541–553. doi:10.1602/neurorx.2.4.541. PMC 1201314. PMID 16489364.