Leonard Cohen

Leonard Cohen | |

|---|---|

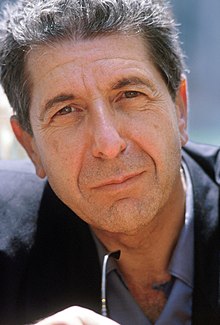

Cohen in 1988 | |

| Born | September 21, 1934 |

| Died | November 7, 2016 (aged 82) Los Angeles, California, US |

| Resting place | Shaar Hashomayim Congregation Cemetery, Montreal, Canada |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1954–2016 |

| Children | 2, including Adam |

| Relatives | Lyon Cohen (grandfather) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Full list |

| Labels | Columbia |

| Website | leonardcohen |

| Signature | |

Leonard Norman Cohen CC GOQ (September 21, 1934 – November 7, 2016) was a Canadian singer-songwriter, poet, and novelist. Themes commonly explored throughout his work include faith and mortality, isolation and depression, betrayal and redemption, social and political conflict, and sexual and romantic love, desire, regret, and loss.[1] He was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He was invested as a Companion of the Order of Canada, the nation's highest civilian honour. In 2011, he received one of the Prince of Asturias Awards for literature and the ninth Glenn Gould Prize.

Cohen pursued a career as a poet and novelist during the 1950s and early 1960s, and did not begin a music career until 1966. His first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967), was followed by three more albums of folk music: Songs from a Room (1969), Songs of Love and Hate (1971) and New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974). His 1977 record Death of a Ladies' Man, co-written and produced by Phil Spector, was a move away from Cohen's previous minimalist sound.

In 1979, Cohen returned with the more traditional Recent Songs, which blended his acoustic style with jazz, East Asian, and Mediterranean influences. Cohen's most famous song, "Hallelujah", was released on his seventh album, Various Positions (1984). I'm Your Man in 1988 marked Cohen's turn to synthesized productions. In 1992, Cohen released its follow-up, The Future, which had dark lyrics and references to political and social unrest.

Cohen returned to music in 2001 with the release of Ten New Songs, a major hit in Canada and Europe. His eleventh album, Dear Heather, followed in 2004. In 2005, Cohen discovered that his manager had stolen most of his money and sold his publishing rights, prompting a return to touring to recoup his losses. Following a successful string of tours between 2008 and 2013, he released three albums in the final years of his life: Old Ideas (2012), Popular Problems (2014), and You Want It Darker (2016), the last of which was released three weeks before his death. His posthumous, fifteenth, and final studio album Thanks for the Dance, was released in November 2019.

In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked him number 103 in their "200 Greatest Singers of All Time" list.[2]

Early life

[edit]Leonard Norman Cohen was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in the Montreal anglophone enclave of Westmount, Quebec, on September 21, 1934. His Lithuanian Jewish mother, Marsha ("Masha") Klonitsky (1905–1978),[3][4] emigrated to Canada in 1927 and was the daughter of Talmudic writer and rabbi Solomon Klonitsky-Kline.[5][6] His paternal grandfather, who had emigrated from Suwałki, in Congress Poland, to Canada, was Canadian Jewish Congress founding president Lyon Cohen. His parents gave him the Hebrew name Eliezer, which means "God helps".[7] His father, clothing store owner Nathan Bernard Cohen (1891–1944),[8] died when Cohen was nine years old. The family attended Congregation Shaar Hashomayim, to which Cohen retained connections for the rest of his life.[9] On the topic of being a kohen, he said in 1967, "I had a very Messianic childhood. I was told I was a descendant of Aaron, the high priest."[10]

Cohen attended Roslyn Elementary School and completed grades seven through nine at Herzliah High School, where his literary mentor (and later inspiration) Irving Layton taught.[11] He then transferred in 1948 to Westmount High School, where he studied music and poetry. He became especially interested in the Spanish poetry of Federico García Lorca.[12] During high school, he was involved in various extracurricular activities, including photography, yearbook, cheerleading, arts club, current events club, and theater. He also served as president of the Students' Council. During that time, he taught himself to play the acoustic guitar and formed a country–folk group that he called the Buckskin Boys. After a young Spanish guitar player taught him "a few chords and some flamenco", he switched to a classical guitar.[12] He has attributed his love of music to his mother, who sang songs around the house: "I know that those changes, those melodies, touched me very much. She would sing with us when I took my guitar to a restaurant with some friends; my mother would come, and we'd often sing all night."[13]

Cohen frequented Montreal's Saint Laurent Boulevard for fun and ate at places such as the Main Deli Steak House.[14][15] According to journalist David Sax, he and one of his cousins would go to the Main Deli to "watch the gangsters, pimps, and wrestlers dance around the night".[16] When he left Westmount, he purchased a place on Saint-Laurent Boulevard in the previously working-class neighbourhood of Little Portugal. He would read his poetry at assorted nearby clubs. In that period and place, he wrote the lyrics to some of his most famous songs.[15]

Poetry and novels

[edit]For six decades, Leonard Cohen revealed his soul to the world through poetry and song—his deep and timeless humanity touching our very core. Simply brilliant. His music and words will resonate forever.

—Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, 2008[17]

In 1951, Cohen enrolled at McGill University, where he became president of the McGill Debating Union and won the Chester MacNaghten Literary Competition for the poems "Sparrows" and "Thoughts of a Landsman".[18] Cohen published his first poem in March 1954 in the magazine CIV/n. The issue also included poems by Cohen's poet–professors (who were also on the editorial board) Irving Layton and Louis Dudek.[18] Cohen graduated from McGill the following year with a B.A. degree.[12] His literary influences during this time included William Butler Yeats, Irving Layton (who taught political science at McGill and became both Cohen's mentor and his friend),[12] Walt Whitman, Federico García Lorca, and Henry Miller.[19] His first published book of poetry, Let Us Compare Mythologies (1956), was published by Dudek as the first book in the McGill Poetry Series the year after Cohen's graduation. The book contained poems written largely when Cohen was between the ages of 15 and 20, and Cohen dedicated the book to his late father.[12] The well-known Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye wrote a review of the book in which he gave Cohen "restrained praise".[12]

After completing his undergraduate degree, Cohen spent a term in the McGill Faculty of Law and then a year (1956–1957) at the Columbia University School of General Studies. Cohen described his graduate school experience as "passion without flesh, love without climax".[20] Consequently, Cohen left New York and returned to Montreal in 1957, working various odd jobs and focusing on the writing of fiction and poetry, including the poems for his next book, The Spice-Box of Earth (1961), which was the first book that Cohen published through the Canadian publishing company McClelland & Stewart. Cohen's first novella and early short stories were not published until 2022 (A Ballet of Lepers).[21] His father's will provided him with a modest trust income sufficient to allow him to pursue his literary ambitions for the time, and The Spice-Box of Earth was successful in helping to expand the audience for Cohen's poetry, helping him reach out to the poetry scene in Canada, outside the confines of McGill University. The book also helped Cohen gain critical recognition as an important new voice in Canadian poetry. One of Cohen's biographers, Ira Nadel, stated that "reaction to the finished book was enthusiastic and admiring...." The critic Robert Weaver found it powerful and declared that Cohen was 'probably the best young poet in English Canada right now.'[12]

Cohen continued to write poetry and fiction throughout the 1960s and preferred to live in quasi-reclusive circumstances after he bought a house on Hydra, a Greek island in the Saronic Gulf. While living and writing on Hydra, Cohen published the poetry collection Flowers for Hitler (1964), and the novel The Favourite Game (1963), an autobiographical Bildungsroman about a young man who discovers his identity through writing.

Cohen was the subject of a 44-minute documentary in 1965 from the National Film Board called Ladies and Gentlemen... Mr. Leonard Cohen.

The 1966 novel Beautiful Losers received a good deal of attention from the Canadian press and stirred up controversy because of a number of sexually graphic passages.[12] Regarding Beautiful Losers, the Boston Globe stated: "James Joyce is not dead. He is living in Montreal under the name of Cohen." In 1966 Cohen also published Parasites of Heaven, a book of poems. Both Beautiful Losers and Parasites of Heaven received mixed reviews and sold few copies.[12]

In 1966, CBC-TV producer Andrew Simon produced a local Montreal current affairs program, Seven on Six, and offered Cohen a position as host. "I decided I'm going to be a songwriter. I want to write songs," Simon recalled Cohen telling him.[22]

Subsequently, Cohen published less, with major gaps, concentrating more on recording songs. In 1966 he wrote "Suzanne", which was performed the same year by The Stormy Clovers, and recorded by Judy Collins on her album In My Life.

In 1978, he published his first book of poetry in many years, Death of a Lady's Man (not to be confused with the album he released the previous year, the similarly titled Death of a Ladies' Man). It was not until 1984 that Cohen published his next book of poems, Book of Mercy, which won him the Canadian Authors Association Literary Award for Poetry. The book contains 50 prose-poems, influenced by the Hebrew Bible and Zen writings. Cohen himself referred to the pieces as "prayers".[23] In 1993 Cohen published Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs, and in 2006, after 10 years of delays, additions, and rewritings, Book of Longing. The Book of Longing is dedicated to the poet Irving Layton. Also, during the late 1990s and 2000s, many of Cohen's new poems and lyrics were first published on the fan website The Leonard Cohen Files, including the original version of the poem "A Thousand Kisses Deep" (which Cohen later adapted for a song).[24][25]

Cohen's writing process, as he told an interviewer in 1998, was "like a bear stumbling into a beehive or a honey cache: I'm stumbling right into it and getting stuck, and it's delicious and it's horrible and I'm in it and it's not very graceful and it's very awkward and it's very painful and yet there's something inevitable about it."[26]

In 2011, Cohen was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for literature.[27] His poetry collection The Flame, which he had been working on at the time of his death, appeared posthumously in 2018.

Cohen's books have been translated into several languages.

Recording career

[edit]1960s and 1970s

[edit]In 1967, disappointed with his lack of success as a writer, Cohen moved to the United States to pursue a career as a folk music singer–songwriter. During the 1960s, he was a fringe figure in Andy Warhol's "Factory" crowd. Warhol speculated that Cohen had spent time listening to Nico in clubs and that this had influenced his musical style.[28]

His song "Suzanne" became a hit for Judy Collins (who subsequently recorded a number of Cohen's other songs), and was for many years his most recorded song. Collins recalls that when she first met him, he said he could not sing or play the guitar, nor did he think "Suzanne" was even a song:

And then he played me "Suzanne" ... I said, "Leonard, you must come with me to this big fundraiser I'm doing" ... Jimi Hendrix was on it. He'd never sung [in front of a large audience] before then. He got out on stage and started singing. Everybody was going crazy—they loved it. And he stopped about halfway through and walked off the stage. Everybody went nuts. ... They demanded that he come back. And I demanded; I said, "I'll go out with you." So we went out, and we sang it. And of course, that was the beginning.[29]

People think Leonard is dark, but actually his sense of humour and his edge on the world is extremely light.

—Judy Collins[30]

She first introduced him to television audiences during one of her shows in 1966,[31] where they performed duets of his songs.[32][33] Still new to bringing his poetry to music, he once forgot the words to "Suzanne" while singing to a different audience.[34] Singers such as Joan Baez have sung it during their tours.[35] Cohen stated that he was duped into giving up the rights for the song, but was glad it happened, as it would be wrong to write a song that was so well loved and to get rich for it also. Collins told Bill Moyers, during a television interview, that she felt Cohen's Jewish background was an important influence on his words and music.[30]

After performing at a few folk festivals, he came to the attention of Columbia Records producer John Hammond, who signed Cohen to a record deal.[36] Cohen's first album was Songs of Leonard Cohen.[37][a] The album was released in the US in late 1967 to generally dismissive reviews,[38] but became a favourite in the UK on its release in early 1968, where it spent over a year on the album charts.[39] He appeared on BBC TV in 1968 where he sang a duet from the album with Julie Felix.[40] Several of the songs on that first album were recorded by other popular folk artists, including James Taylor[41] and Judy Collins.[42] Cohen followed up that first album with Songs from a Room (1969, featuring the often-recorded "Bird on the Wire") and Songs of Love and Hate (1971).

In 1971, film director Robert Altman featured the songs "The Stranger Song", "Winter Lady", and "Sisters of Mercy", originally recorded for Songs of Leonard Cohen, in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Scott Tobias wrote in 2014 that "The film is unimaginable to me without the Cohen songs, which function as these mournful interstitials that unify the entire movie."[43] Tim Grierson wrote in 2016, shortly after Cohen's death, that '"Altman's and Cohen's legacies would forever be linked by McCabe. The movie is inextricably connected to Cohen's songs. It's impossible to imagine Altman's masterpiece without them."[44]

In 1970, Cohen toured for the first time, in the United States, Canada, and Europe, and appeared at the Isle of Wight Festival.[45] In 1972 he toured again in Europe and Israel, captured on film by Tony Palmer and eventually released in 2010 under the title 'Bird on a Wire'.[b] When his performance in Israel did not seem to be going well he walked off the stage, went to his dressing room, and took some LSD. He then heard the audience clamouring for his reappearance by singing to him in Hebrew, and under the influence of the psychedelic, he returned to finish the show.[47][48]

A Jew remains a Jew. Now it’s war and there’s no need for explanations. My name is Cohen, no?

—Leonard Cohen[49]

In 1973, when Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on the Yom Kippur day, Cohen arrived in Israel. He had no guitar, and intended to volunteer in some kibbutz for the harvest, though he had no solid plan. He was spotted in a Tel Aviv Pinati Café by Israeli musicians Oshik Levi, Matti Caspi and Ilana Rovina, who offered him to go together to Sinai to sing for Israeli soldiers.[50][49][51] Even though he reportedly voiced "pro-Arab political views" before the war, he said after the war "I am joining my brothers fighting in the desert. I don't care if their war is just or not. I know only that war is cruel, that it leaves bones, blood and ugly stains on the holy soil."[49] Cohen played his most-known songs to the troops: "Suzanne", "So Long Marianne", "Bird on the Wire", and his new song he called "Lover Lover Lover".[52] In Sinai, Cohen was introduced to the Major General Ariel Sharon, future Prime Minister of Israel.[49] Cohen later described the improvised concerts:[49]

"We would just drop into little places, like a rocket site and they would shine their flashlights at us and we would sing a few songs. Or they would give us a jeep and we would go down the road towards the front and wherever we saw a few soldiers waiting for a helicopter or something like that we would sing a few songs. And maybe back at the airbase we would do a little concert, maybe with amplifiers. It was very informal, and you know, very intense."

In 1974 Cohen released a new album, New Skin for the Old Ceremony, with songs inspired by the war. "Lover Lover Lover", was written and performed in Sinai. "Who By Fire", written reflecting on the war, takes its name from the Yom Kippur prayer, the Unetaneh Tokef.[51][53][49] Other songs inspired by the war are "Field Commander Cohen" and "There is a War".[49] In 1976, Cohen said during the concert that his now famous song was written for "the Egyptians and the Israelis", though he wrote and performed the song for the Israeli soldiers during the war, and the song originally contained the lines "I went down to the desert to help my brothers fight".[52]

In 1973, Columbia Records released Cohen's first concert album, Live Songs. Then beginning around 1974, Cohen's collaboration with pianist and arranger John Lissauer created a live sound praised by the critics. They toured together in 1974 in Europe, the US and Canada in late 1974 and early 1975, in support of Cohen's record New Skin for the Old Ceremony. In late 1975 Cohen and Lissauer performed a short series of shows in the US and Canada with a new band, in support of Cohen's Best Of release. The tour included new songs from an album in progress, co-written by Cohen and Lissauer and titled Songs for Rebecca. None of the recordings from these live tours with Lissauer were ever officially released, and the album was abandoned in 1976.

In 1976, Cohen embarked on a new major European tour with a new band and changes in his sound and arrangements, again, in support of his The Best of Leonard Cohen release (in Europe retitled as Greatest Hits). Laura Branigan was one of his backup singers during the tour.[54] From April to July, Cohen gave 55 shows, including his first appearance at the famous Montreux Jazz Festival.

After the European tour of 1976, Cohen again attempted a new change in his style and arrangements: his new 1977 record, Death of a Ladies' Man was co-written and produced by Phil Spector.[55][c] One year later, in 1978, Cohen published a volume of poetry with the subtly revised title, Death of a Lady's Man.

Leonard acknowledges that the whole act of living contains immense amounts of sorrow and hopelessness and despair; and also passion, high hopes, deep love, and eternal love.

—Jennifer Warnes, describing Cohen's lyrics[58]

In 1979, Cohen returned with the more traditional Recent Songs,[59] which blended his acoustic style with jazz and East Asian and Mediterranean influences. Beginning with this record, Cohen began to co-produce his albums. Produced by Cohen and Henry Lewy (Joni Mitchell's sound engineer), Recent Songs included performances by Passenger,[60] an Austin-based jazz–fusion band that met Cohen through Mitchell. The band helped Cohen create a new sound by featuring instruments like the oud, the Gypsy violin, and the mandolin. The album was supported by Cohen's major tour with the new band, and Jennifer Warnes and Sharon Robinson on the backing vocals, in Europe in late 1979, and again in Australia, Israel, and Europe in 1980. In 2000, Columbia released an album of live recordings of songs from the 1979 tour, titled Field Commander Cohen: Tour of 1979.[61]

During the 1970s, Cohen toured twice with Jennifer Warnes as a backup singer (1972 and 1979). Warnes would become a fixture on Cohen's future albums, receiving full co-vocals credit on Cohen's 1984 album Various Positions (although the record was released under Cohen's name, the inside credits say "Vocals by Leonard Cohen and Jennifer Warnes"). In 1987 she recorded an album of Cohen songs, Famous Blue Raincoat.[62] Cohen said that she sang backup for his 1980 tour, even though her career at the time was in much better shape than his. "So this is a real friend", he said. "Someone who in the face of great derision, has always supported me."[58]

1980s

[edit]

In the early 1980s, Cohen co-wrote (with Lewis Furey) the rock musical film Night Magic starring Carole Laure and Nick Mancuso. Columbia declined to release his 1984 LP Various Positions in the United States.[d] Cohen supported the release of the album with his biggest tour to date, in Europe and Australia, and with his first tour in Canada and the United States since 1975.[e] The band performed at the Montreux Jazz Festival, and the Roskilde Festival.

They also gave a series of highly emotional and politically controversial concerts in Poland, which had been under martial law just two years before, and performed the song "The Partisan", regarded as the hymn of the Polish Solidarity movement.[63][f]

In 1987, Jennifer Warnes's tribute album Famous Blue Raincoat helped restore Cohen's career in the US. The following year he released I'm Your Man.[g] Cohen supported the record with a series of television interviews and an extensive tour of Europe, Canada, and the US. Many shows were broadcast on European and US television and radio stations, while Cohen performed for the first time in his career on PBS's Austin City Limits show.[65][66][h]

"Hallelujah"

[edit]"Hallelujah" was first released on Cohen's studio album Various Positions in 1984, and he sang it during his Europe tour in 1985.[67][68][69] The song had limited initial success but found greater popularity through a 1991 cover by John Cale, which formed the basis for a later cover by Jeff Buckley.[70] "Hallelujah" has been performed by almost 200 artists in various languages.[71][i] New York Times movie reviewer A. O. Scott wrote that "Hallelujah is one of those rare songs that survives its banalization with at least some of its sublimity intact".[73]

The song is the subject of the 2012 book The Holy or the Broken by Alan Light and the 2022 documentary film Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song by Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine.[74] Janet Maslin's New York Times book review said that Cohen spent years struggling with the song, which eventually became "one of the most haunting, mutable and oft-performed songs in American musical history".[75]

1990s

[edit]The album track "Everybody Knows" from I'm Your Man and "If It Be Your Will" in the 1990 film Pump Up the Volume helped expose Cohen's music to a wider audience. He first introduced the song during his world tour in 1988.[76] The song "Everybody Knows" also featured prominently in fellow Canadian Atom Egoyan's 1994 film, Exotica. In 1992, Cohen released The Future, which urges (often in terms of biblical prophecy) perseverance, reformation, and hope in the face of grim prospects. Three tracks from the album – "Waiting for the Miracle", "The Future" and "Anthem" – were featured in the movie Natural Born Killers, which also promoted Cohen's work to a new generation of US listeners.

As with I'm Your Man, the lyrics on The Future were dark, and made references to political and social unrest. The title track is reportedly a response to the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Cohen promoted the album with two music videos, for "Closing Time" and "The Future", and supported the release with the major tour through Europe, United States and Canada, with the same band as in his 1988 tour, including a second appearance on PBS's Austin City Limits. Some of the Scandinavian shows were broadcast live on the radio. The selection of performances, mostly recorded on the Canadian leg of the tour, was released on the 1994 Cohen Live album.

In 1993, Cohen also published his book of selected poems and songs, Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs, on which he had worked since 1989. It includes a number of new poems from the late 1980s and early 1990s and major revision of his 1978 book Death of a Lady's Man.[77]

In 1994, Cohen retreated to the Mt. Baldy Zen Center near Los Angeles, beginning what became five years of seclusion at the center.[62] In 1996, Cohen was ordained as a Rinzai Zen Buddhist monk and took the Dharma name Jikan, meaning "silence". He served as personal assistant to Kyozan Joshu Sasaki Roshi.

In 1997, Cohen oversaw the selection and release of the More Best of Leonard Cohen album, which included a previously unreleased track, "Never Any Good", and an experimental piece "The Great Event". The first was left over from Cohen's unfinished mid-1990s album, which was tentatively called On The Path, and slated to include songs like "In My Secret Life" (already recited as a song-in-progress in 1988) and "A Thousand Kisses Deep",[78] both later re-worked with Sharon Robinson for the 2001 album Ten New Songs.[79]

Although there was a public impression that Cohen would not resume recording or publishing, he returned to Los Angeles in May 1999. He began to contribute regularly to The Leonard Cohen Files fan website, emailing new poems and drawings from Book of Longing and early versions of new songs, like "A Thousand Kisses Deep" in September 1998[80] and Anjani Thomas's story sent on May 6, 1999, the day they were recording "Villanelle for our Time"[81] (released on 2004's Dear Heather album). The section of The Leonard Cohen Files with Cohen's online writings has been titled "The Blackening Pages".[25]

2000s

[edit]Post-monastery records

[edit]After two years of production, Cohen returned to music in 2001 with the release of Ten New Songs, featuring a major influence from producer and co-composer Sharon Robinson. The album, recorded at Cohen's and Robinson's home studios – Still Life Studios,[82] includes the song "Alexandra Leaving", a transformation of the poem "The God Abandons Antony", by the Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy. The album was a major hit for Cohen in Canada and Europe, and he supported it with the hit single "In My Secret Life" and accompanying video shot by Floria Sigismondi. The album won him four Canadian Juno Awards in 2002: Best Artist, Best Songwriter, Best Pop Album, and Best Video ("In My Secret Life").[79] In October 2003 he was named a Companion of the Order of Canada, the country's highest civilian honour.[79]

In October 2004, Cohen released Dear Heather, largely a musical collaboration with jazz chanteuse (and romantic partner) Anjani Thomas, although Sharon Robinson returned to collaborate on three tracks (including a duet). As light as the previous album was dark, Dear Heather reflects Cohen's own change of mood – he said in a number of interviews that his depression had lifted in recent years, which he attributed to Zen Buddhism. In an interview following his induction into the Canadian Songwriters' Hall of Fame, Cohen explained that the album was intended to be a kind of notebook or scrapbook of themes, and that a more formal record had been planned for release shortly afterwards, but that this was put on ice by his legal battles with his ex-manager.

Blue Alert, an album of songs co-written by Anjani and Cohen, was released in 2006 to positive reviews. Sung by Anjani, who according to one reviewer "... sounds like Cohen reincarnated as woman ... though Cohen doesn't sing a note on the album, his voice permeates it like smoke."[83][j]

Before embarking on his 2008–2010 world tour, and without finishing the new album that had been in work since 2006, Cohen contributed a few tracks to other artists' albums – a new version of his own "Tower of Song" was performed by him, Anjani Thomas and U2 in the 2006 tribute film Leonard Cohen I'm Your Man[85] (the video and track were included on the film's soundtrack and released as the B-side of U2's single "Window in the Skies", reaching No 1 in the Canadian Singles Chart). In 2007 he recited "The Sound of Silence" on the album Tribute to Paul Simon: Take Me to the Mardi Gras and "The Jungle Line" by Joni Mitchell, accompanied by Herbie Hancock on piano, on Hancock's Grammy-winning album River: The Joni Letters,[86] while in 2008, he recited the poem "Since You've Asked" on the album Born to the Breed: A Tribute to Judy Collins.[87][88]

Lawsuits and financial troubles

[edit]In late 2005, Cohen's daughter Lorca began to suspect his longtime manager, Kelley Lynch, of financial impropriety. According to the Cohen biographer Sylvie Simmons, Lynch handled Cohen's business affairs and was a close family friend.[89] Cohen discovered that he had unknowingly paid a credit card bill of Lynch's for $75,000, and that most of the money in his accounts was gone, including money from his retirement accounts and charitable trust funds. This had begun as early as 1996, when Lynch started selling Cohen's music publishing rights, despite the fact that Cohen had had no financial incentive to do so.[89]

In October 2005, Cohen sued Lynch, alleging that she had misappropriated more than US$5 million from his retirement fund, leaving only $150,000.[90][91] Cohen was sued in turn by other former business associates.[90] The events drew media attention, including a cover feature with the headline "Devastated!" in the Canadian magazine Maclean's.[91] In March 2006, Cohen won a civil suit and was awarded US$9 million by a Los Angeles County superior court. Lynch ignored the suit and did not respond to a subpoena issued for her financial records.[92] NME reported that Cohen might never be able to collect the awarded amount.[93][k] In 2012, Lynch was jailed for 18 months and given five years' probation for harassing Cohen after he dismissed her.[100]

Book of Longing

[edit]Cohen published a book of poetry and drawings, Book of Longing, in May 2006. In March, a Toronto-based retailer offered signed copies to the first 1,500 orders placed online: all 1,500 sold within hours. The book quickly topped bestseller lists in Canada. On May 13, Cohen made his first public appearance in 13 years, at an in-store event at a bookstore in Toronto. Approximately 3,000 people arrived, causing the streets surrounding the bookstore to be closed. He sang two of his earliest and best-known songs: "So Long, Marianne" and "Hey, That's No Way to Say Goodbye", accompanied by the Barenaked Ladies and Ron Sexsmith. Appearing with him was Anjani, promoting her new CD along with his book.[101]

That same year, Philip Glass composed music for Book of Longing. Following a series of live performances that included Glass on keyboards, Cohen's recorded spoken text, four additional voices (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, and bass-baritone), and other instruments, and as well as screenings of Cohen's artworks and drawings, Glass' label Orange Mountain Music released a double CD of the work, titled Book of Longing. A Song Cycle based on the Poetry and Artwork of Leonard Cohen.[102]

2008–2010 World Tour

[edit]2008 tour

[edit]To recoup the money his ex-manager had stolen, Cohen embarked on his first world tour in 15 years. He said that being "forced to go back on the road to repair the fortunes of my family and myself ... [was] a most fortunate happenstance because I was able to connect... with living musicians. And I think it warmed some part of my heart that had taken on a chill."[100]

The tour began on May 11 in Fredericton, New Brunswick, and was extended until late 2010. The schedule of the first leg in mid-2008 encompassed Canada and Europe, including performances at The Big Chill,[103] the Montreal Jazz Festival, and on the Pyramid Stage at the 2008 Glastonbury Festival on June 29, 2008.[104] His performance at Glastonbury was hailed by many as the highlight of the festival,[105] and his performance of "Hallelujah" as the sun set received a rapturous reception and a lengthy ovation from a packed Pyramid Stage field.[106] He also played two shows in London's O2 Arena.[107]

In Dublin, Cohen was the first performer to play an open-air concert at IMMA (Royal Hospital Kilmainham) ground, performing there on June 13, 14 and 15, 2008. In 2009, the performances were awarded Ireland's Meteor Music Award as the best international performance of the year.

In September, October and November 2008, Cohen toured Europe, including stops in Austria, Ireland, Poland, Romania, Italy, Germany, France and Scandinavia.[citation needed] In March 2009, Cohen released Live in London, recorded in July 2008 at London's O2 Arena and released on DVD and as a two-CD set. The album contains 25 songs and is more than two and one-half hours long. It was the first official DVD in Cohen's recording career.[108]

2009 tour

[edit]

The third leg of Cohen's World Tour 2008–2009 encompassed New Zealand and Australia from January 20 to February 10, 2009. In January 2009, The Pacific Tour first came to New Zealand, where the audience of 12,000 responded with five standing ovations.[l]

On February 19, 2009, Cohen played his first American concert in 15 years at the Beacon Theatre in New York City.[111] The show, showcased as the special performance for fans, Leonard Cohen Forum members and press, was the only show in the whole three-year tour that was broadcast on the radio (NPR) and available as a free podcast.

The North American Tour of 2009 opened on April 1, and included the performance at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on Friday, April 17, 2009, in front of one of the largest outdoor theatre crowds in the history of the festival. His performance of Hallelujah was widely regarded as one of the highlights of the festival, thus repeating the major success of the 2008 Glastonbury appearance.

In July 2009, Cohen started his marathon European tour, his third in two years. The itinerary mostly included sport arenas and open air Summer festivals in Germany, UK, France, Spain, Ireland (the show at O2 in Dublin won him the second Meteor Music Award in a row), but also performances in Serbia in the Belgrade Arena, in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Turkey, and again in Romania.

On September 18, 2009, on the stage at a concert in Valencia, Spain, Cohen suddenly fainted halfway through performing his song "Bird on the Wire", the fourth in the two-act set list; Cohen was brought down backstage by his band members and then admitted to local hospital, while the concert was suspended.[112] It was reported that Cohen had stomach problems, and possibly food poisoning.[113] Three days later, on September 21, his 75th birthday, he performed in Barcelona. The show, last in Europe in 2009 and rumoured to be the last European concert ever, attracted many international fans, who lit the green candles honouring Cohen's birthday, leading Cohen to give a special speech of thanks for the fans and the Leonard Cohen Forum.

The last concert of this leg was held in Tel Aviv, Israel, on September 24 at Ramat Gan Stadium. The event was surrounded by public discussion due to a cultural boycott of Israel proposed by a number of musicians.[114] Nevertheless, tickets for the Tel Aviv concert, Cohen's first performance in Israel since 1980, sold out in less than 24 hours.[115] It was announced that the proceeds from the sale of the 47,000 tickets would go into a charitable fund in partnership with Amnesty International and would be used by Israeli and Palestinian peace groups;[116] however, Amnesty later withdrew.[117][m] Cohen was scheduled to perform in Ramallah two days later, but the organizers cancelled the show due to criticism of Palestinian activists. The PACBI stated that: "Ramallah will not receive Cohen as long as he is intent on whitewashing Israel's colonial apartheid regime by performing in Israel".[114][121]

The sixth leg of the 2008–2009 world tour went again to the US, with 15 shows. The 2009 world tour earned a reported $9.5 million, putting Cohen at number 39 on Billboard magazine's list of the year's top musical "money makers".[122]

On September 14, 2010, Sony Music released a live CD/DVD album, Songs from the Road, showcasing Cohen's 2008 and 2009 live performances. The previous year, Cohen's performance at the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival was released as a CD/DVD combo.

2010 tour

[edit]Officially billed as the "World Tour 2010", the tour started on July 25, 2010, in Arena Zagreb, Croatia, and continued with stops in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Scandinavia, and Ireland, where on July 31, 2010, Cohen performed at Lissadell House in County Sligo. It was Cohen's eighth Irish concert in just two years after a hiatus of more than 20 years.[123] On August 12, Cohen played the 200th show of the tour in Scandinavium, Gothenburg, Sweden.[citation needed] The third leg of the 2010 tour started on October 28 in New Zealand and continued in Australia.

2010s

[edit]

In 2011, Cohen's poetical output was represented in Everyman's Library Pocket Poets, in a selection Poems and Songs edited by Robert Faggen. The collection included a selection from all Cohen's books, based on his 1993 books of selected works, Stranger Music, and as well from Book of Longing, with addition of six new song lyrics. Nevertheless, three of those songs, "A Street", recited in 2006, "Feels So Good", performed live in 2009 and 2010, and "Born in Chains", performed live in 2010, were not released on Cohen's 2012 album Old Ideas, with him being unhappy with the versions of the songs in the last moment; the song "Lullaby", as presented in the book and performed live in 2009, was completely re-recorded for the album, presenting new lyrics on the same melody.[citation needed]

A biography, I'm Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen, written by Sylvie Simmons, was published in October 2012. The book is the second major biography of Cohen (Ira Nadel's 1997 biography Various Positions was the first).[124]

Old Ideas

[edit]Leonard Cohen's 12th studio album, Old Ideas, was released worldwide on January 31, 2012, and it soon became the highest-charting album of his entire career, reaching No. 1 positions in Canada, Norway, Finland, Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Croatia, New Zealand, and top ten positions in United States, Australia, France, Portugal, UK, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Ireland, Germany, and Switzerland, competing for number one position with Lana Del Rey's debut album Born to Die, released the same day.[125]

The lyrics for the song "Going Home" were published as a poem in The New Yorker magazine in January 2012, prior to the record's release.[126] The entire album was streamed online by NPR on January 22[127] and on January 23 by The Guardian.[128]

The album received uniformly positive reviews from Rolling Stone,[129] the Chicago Tribune,[130] and The Guardian.[131] At a record release party for the album in January 2012, Cohen spoke with The New York Times reporter Jon Pareles who states that "mortality was very much on his mind and in his songs [on this album]." Pareles goes to characterize the album as "an autumnal album, musing on memories and final reckonings, but it also has a gleam in its eye. It grapples once again with topics Mr. Cohen has pondered throughout his career: love, desire, faith, betrayal, redemption. Some of the diction is biblical; some is drily sardonic."[132]

2012–2013 World Tour

[edit]

On August 12, 2012, Cohen embarked on a new European tour in support of Old Ideas, adding a violinist to his 2008–2010 tour band, now nicknamed Unified Heart Touring Band, and following the same three-hour set list structure as in 2008–2012 tour, with the addition of a number of songs from Old Ideas. The European leg ended on October 7, 2012, after concerts in Belgium, Ireland (Royal Hospital), France (Olympia in Paris), England (Wembley Arena in London), Spain, Portugal, Germany, Italy (Arena in Verona), Croatia (Arena in Pula), Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Romania and Turkey.[133]

The second leg of the Old Ideas World Tour took place in the US and Canada in November and December, with 56 shows altogether on both legs.[134]

Cohen returned to North America in the spring of 2013 with concerts in the United States and Canada. A summer tour of Europe happened shortly afterwards.[135]

Cohen then toured Australia and New Zealand in November and December 2013. His final concert was performed at the Vector Arena in Auckland.[136][137]

Popular Problems and You Want It Darker

[edit]Cohen released his 13th album, Popular Problems, on September 24, 2014.[138] The album includes "A Street", which he had previously recited in 2006, during promotion of his book of poetry Book of Longing, and later printed twice, as "A Street" in the March 2, 2009, issue of The New Yorker magazine,[139] and appeared as "Party's Over" in Everyman's Library edition of Poems and Songs in 2011.

Cohen's 14th and final album, You Want It Darker, was released on October 21, 2016.[140] Cohen's son Adam Cohen has a production credit on the album.[141] On February 23, 2017, Cohen's son and his final album collaborator Sammy Slabbinck released a special, posthumous tribute video set to the album track "Traveling Light", featuring never before seen archival footage of Cohen from his career.[142] The title track was awarded a Grammy Award for Best Rock Performance in January 2018.

Thanks for the Dance and other posthumous releases

[edit]Before his death, Cohen had begun working on a new album with his son Adam, a musician and singer-songwriter.[143] The album, titled Thanks for the Dance, was released on November 22, 2019.[144] One posthumous track, "Necropsy of Love", appeared on the 2018 compilation album The Al Purdy Songbook and another track named "The Goal" was also published on September 20, 2019, on Leonard Cohen's official YouTube channel.[145]

Cultural impact and themes

[edit]Over a musical career that spanned nearly five decades, Mr. Cohen wrote songs that addressed—in spare language that could be both oblique and telling—themes of love and faith, despair and exaltation, solitude and connection, war and politics.[146]

It's inevitable that Mr. Cohen will be remembered above all for his lyrics. They are terse and acrobatic, scriptural and bawdy, vividly descriptive and enduringly ambiguous, never far from either a riddle or a punch line.[147]

The New York Times:

Obituary, Nov. 10, 2016, and

"An Appraisal", Nov. 11, 2016

Writing for AllMusic, critic Bruce Eder assessed Cohen's overall career in popular music by asserting that "[he is] one of the most fascinating and enigmatic ... singer-songwriters of the late '60s ... Second only to Bob Dylan (and perhaps Paul Simon), he commands the attention of critics and younger musicians more firmly than any other musical figure from the 1960s who continued to work in the 21st century."[148] The Academy of American Poets commented more broadly, stating that "Cohen's successful blending of poetry, fiction, and music is made most clear in Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs, published in 1993 ... while it may seem to some that Leonard Cohen departed from the literary in pursuit of the musical, his fans continue to embrace him as a Renaissance man who straddles the elusive artistic borderlines."[149] Bob Dylan was an admirer, describing Cohen as the 'number one' songwriter of their time (Dylan described himself as 'number zero'). "When people talk about Leonard, they fail to mention his melodies, which to me, along with his lyrics, are his greatest genius. ... Even the counterpoint lines--they give a celestial character & melodic lift to his songs. ... no one else comes close to this in modern music. ... I like all of Leonard's songs, early or late. ... they make you think & feel. I like some of his later songs even better than his early ones. Yet there's a simplicity to his early ones that I like, too. ... He's very much a descendant of Irving Berlin. ... Both of them just hear melodies that most of us can only strive for. ... Both Leonard & Berlin are incredibly crafty. Leonard particularly uses chord progressions that are classical in shape. He is a much more savvy musician than you'd think."[150]

Themes of political and social justice also recur in Cohen's work, especially in later albums. In "Democracy", he both acknowledges political problems and celebrates [citation needed] the hopes of reformers: "from the wars against disorder/ from the sirens night and day/ from the fires of the homeless/ from the ashes of the gay/ Democracy is coming to the USA."[151] He made the observation in "Tower of Song" that "the rich have got their channels in the bedrooms of the poor/ And there's a mighty judgment coming." In the title track of The Future he recasts this prophecy on a pacifist note: "I've seen the nations rise and fall/ ... / But love's the only engine of survival." In that same song he comments on current topics (abortion, anal sex and the use of drugs): "Give me crack and anal sex. Take the only tree that's left and stuff it up the hole in your culture", "Destroy another fetus now, we don't like children anyhow".[152][153] In "Anthem", he promises that "the killers in high places [who] say their prayers out loud/ [are] gonna hear from me."

War is an enduring theme of Cohen's work that—in his earlier songs and early life—he approached ambivalently. Challenged in 1974 over his serious demeanor in concerts and the military salutes he ended them with, Cohen remarked, "I sing serious songs, and I'm serious onstage because I couldn't do it any other way ... I don't consider myself a civilian. I consider myself a soldier, and that's the way soldiers salute."[154]

It is a beautiful thing for us to be so deeply interested in each other. You have to write about something. Women stand for the objective world for a man, and they stand for the thing that you're not. And that's what you always reach for in a song.

—Leonard Cohen, 1979[155]

Deeply moved by encounters with Israeli and Arab soldiers, he left the country to write "Lover Lover Lover". This song has been interpreted as a personal renunciation of armed conflict, and ends with the hope his song will serve a listener as "a shield against the enemy". He would later remark, "'Lover, Lover, Lover' was born over there; the whole world has its eyes riveted on this tragic and complex conflict. Then again, I am faithful to certain ideas, inevitably. I hope that those of which I am in favour will gain."[156] Asked which side he supported in the Arab-Israeli conflict, Cohen responded, "I don't want to speak of wars or sides ... Personal process is one thing, it's blood, it's the identification one feels with their roots and their origins. The militarism I practice as a person and a writer is another thing. ... I don't wish to speak about war."[157]

In 1991, playwright Bryden MacDonald launched Sincerely, A Friend, a musical revue based on Cohen's music.[158]

Cohen is mentioned in the Nirvana song "Pennyroyal Tea" from the band's 1993 release, In Utero. Kurt Cobain wrote, "Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld/So I can sigh eternally." Cohen, after Cobain's suicide, was quoted as saying "I'm sorry I couldn't have spoken to the young man. I see a lot of people at the Zen Centre, who have gone through drugs and found a way out that is not just Sunday school. There are always alternatives, and I might have been able to lay something on him."[159] He is also mentioned in the lyrics of songs by Lloyd Cole & The Commotions,[160] Mercury Rev and Marillion.[161][162]

Cohen was one of the inspirations for Matt Bissonnette and Steven Clark's 2002 film Looking for Leonard. Centred on a group of small-time criminals in Montreal, one of the film's characters idolizes Cohen as a symbol of her dreams for a better life, obsessively rereading his writings and rewatching Ladies and Gentlemen.[163] Bissonnette followed up in 2020 with Death of a Ladies' Man, a film that uses seven Cohen songs in its soundtrack to illuminate key themes in the film's screenplay.[164]

The Leonard Cohen song "So Long, Marianne" is the title of the season 4, episode 9 episode of This Is Us. The song is played and its meaning is discussed as an important plot point of the episode.

In April 2022, author and journalist Matti Friedman published "Who By Fire: War, Atonement, and the Resurrection of Leonard Cohen"[165][166] the story of Leonard Cohen's 1973 tour to the front lines of the Yom Kippur War.[167] TV miniseries by Yehonatan Indursky based on the book is expected in 2024.[168]

Susan Cain, author of Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole (2022), said that humorous references to Cohen as the "Poet Laureate of Pessimism"[169] miss the point that Cohen's life suggests that "the quest to transform pain into beauty is one of the great catalysts of artistic expression".[170] Cain dedicated the book "In memory of Leonard Cohen", quoting lyrics from Cohen's song "Anthem" (1992): "There is a crack, a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in."[171]

New York Times critic A. O. Scott wrote that "Cohen wasn't one to offer comfort. His gift as a songwriter and performer was rather to provide commentary and companionship amid the gloom, offering a wry, openhearted perspective on the puzzles of the human condition".[73] Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine, creators of the 2022 documentary film Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song, acknowledged that Cohen was initially perceived as a "monster of gloom"; but Goldfine described Cohen as "one of the funniest guys ever" with "a very droll, dry wit",[172] and Geller remarking, "Almost everything (Cohen) said came out with a twinkle in his eye".[173] Long before his death, Cohen said "I feel I have a huge posthumous career in front of me".[174]

Suzanne Vega spoke of Leonard Cohen's admirers in a New Yorker interview, saying that knowing his work was like being part of a "secret society" among people of her generation.[175]

Personal life

[edit]Relationships and children

[edit]In September 1960, Cohen bought a house on the Greek island of Hydra with $1,500 that he had inherited from his grandmother.[176] Cohen lived there with Marianne Ihlen, with whom he was in a relationship for most of the 1960s.[36] The song "So Long, Marianne" was written to and about her. In 2016, Ihlen died of leukemia three months and nine days before Cohen.[177][178] His farewell letter to her was read at her funeral, often misquoted by the media and others as "... our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine."[179] This widely circulated version is based on an inaccurate verbal recollection by Ihlen's friend. The letter (actually an email), obtained through the Leonard Cohen estate, reads:

Dearest Marianne,

I'm just a little behind you, close enough to take your hand. This old body has given up, just as yours has too.

I've never forgotten your love and your beauty. But you know that. I don't have to say any more. Safe travels old friend. See you down the road. Endless love and gratitude.

— your Leonard, [180]

In the spring of 1968, Cohen had a brief relationship with musician Janis Joplin while staying at the Chelsea Hotel, and the song of the same name references this relationship.[181][182] Cohen also had well-known relationships with Canadian singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell and actress Rebecca De Mornay.[183]

In the 1970s, Cohen was in a relationship with artist Suzanne Elrod. She took the cover photograph for Live Songs and is pictured on the cover of the Death of a Ladies' Man. She also inspired the "Dark Lady" of Cohen's book Death of a Lady's Man (1978), but is not the subject of one of his best-known songs, "Suzanne", which refers to Suzanne Verdal, the former wife of a friend, the Québécois sculptor Armand Vaillancourt.[184] Cohen and Elrod separated in 1979;[185] he later stated that "cowardice" and "fear" prevented him from marrying her.[186][187] Their relationship produced two children: a son, Adam (b. 1972), and a daughter, Lorca (b. 1974), named after poet Federico García Lorca. Adam is a singer–songwriter and the lead singer of pop-rock band Low Millions, while Lorca is a photographer. She shot the music video for Cohen's song "Because Of" (2004), and worked as a photographer and videographer for his 2008–10 world tour. Cohen had three grandchildren: grandson Cassius through his son Adam, and granddaughter Viva (whose father is musician Rufus Wainwright) and grandson Lyon through Lorca.[188][189]

Cohen was in a relationship with French photographer Dominique Issermann in the 1980s. They worked together on several occasions: she shot his first two music videos for the songs "Dance Me to the End of Love" and "First We Take Manhattan" and her photographs were used for the covers of his 1993 book Stranger Music and his album More Best of Leonard Cohen and for the inside booklet of I'm Your Man (1988), which he also dedicated to her.[190] In 2010, she was also the official photographer of his world tour.

In the 1990s, Cohen was romantically linked to actress Rebecca De Mornay.[191] De Mornay co-produced Cohen's 1992 album The Future, which is also dedicated to her with an inscription that quotes Rebecca's coming to the well from the Book of Genesis chapter 24 and giving drink to Eliezer's camels, after he prayed for guidance; Eliezer ("God is my help" in Hebrew) is part of Cohen's Hebrew name (Eliezer ben Nisan ha'Cohen), and Cohen sometimes referred to himself as "Eliezer Cohen" or even "Jikan Eliezer".[192][193]

Religious beliefs and practices

[edit]Cohen was described as a Sabbath-observant Jew in an article in The New York Times: "Mr. Cohen keeps the Sabbath even while on tour and performed for Israeli troops during the Yom Kippur War 1973. So how does he square that faith with his continued practice of Zen? 'Allen Ginsberg asked me the same question many years ago,' he said. 'Well, for one thing, in the tradition of Zen that I've practiced, there is no prayerful worship and there is no affirmation of a deity. So theologically there is no challenge to any Jewish belief.'"[194]

Cohen had a brief phase around 1970 of being interested in a variety of world views, which he later described as "from the Communist party to the Republican Party" and "from Scientology to delusions of me as the High Priest rebuilding the Temple".[195]

Cohen was involved with Buddhism beginning in the 1970s and was ordained a Rinzai Buddhist monk in 1996. However, he continued to consider himself Jewish: "I'm not looking for a new religion. I'm quite happy with the old one, with Judaism."[196] Beginning in the late 1970s, Cohen was associated with Buddhist monk and rōshi (venerable teacher) Kyozan Joshu Sasaki, regularly visiting him at Mount Baldy Zen Center and serving him as personal assistant during Cohen's period of reclusion at Mount Baldy monastery in the 1990s. Sasaki appears as a regular motif or addressee in Cohen's poetry, especially in his Book of Longing, and took part in a 1997 documentary about Cohen's monastery years, Leonard Cohen: Spring 1996. Cohen's 2001 album Ten New Songs and his 2014 album Popular Problems are dedicated to Joshu Sasaki.

Leonard also showed an interest in the teachings of Ramesh Balsekar, who taught from the tradition of Advaita Vedanta.[197]

In a 1993 interview titled "I am the little Jew who wrote the Bible", he said: "At our best, we inhabit a biblical landscape, and this is where we should situate ourselves without apology. [...] That biblical landscape is our urgent invitation ... Otherwise, it's really not worth saving or manifesting or redeeming or anything, unless we really take up that invitation to walk into that biblical landscape."

Cohen showed an interest in Jesus as a universal figure, saying, "I'm very fond of Jesus Christ. He may be the most beautiful guy who walked the face of this earth. Any guy who says 'Blessed are the poor. Blessed are the meek' has got to be a figure of unparalleled generosity and insight and madness ... A man who declared himself to stand among the thieves, the prostitutes and the homeless. His position cannot be comprehended. It is an inhuman generosity. A generosity that would overthrow the world if it was embraced because nothing would weather that compassion. I'm not trying to alter the Jewish view of Jesus Christ. But to me, in spite of what I know about the history of legal Christianity, the figure of the man has touched me."[198]

Speaking about his religion in a 2007 interview for BBC Radio 4's Front Row (partially re-broadcast on November 11, 2016), Cohen said: "My friend Brian Johnson said of me that I'd never met a religion I didn't like. That's why I've tried to correct that impression [that I was looking for another religion besides Judaism] because I very much feel part of that tradition and I practice that and my children practice it, so that was never in question. The investigations that I've done into other spiritual systems have certainly illuminated and enriched my understanding of my own tradition."[199]

At his concert in Ramat Gan on September 24, 2009, Cohen spoke Jewish prayers and blessings to the audience in Hebrew. He opened the show with the first sentence of Ma Tovu. At the middle, he used Baruch Hashem, and he ended the concert reciting the blessing of Birkat Kohanim.[200]

Death and tributes

[edit]

Cohen died on November 7, 2016, at the age of 82 at his home in Los Angeles; leukemia was a contributing cause.[201][202][203] According to his manager, Cohen's death was the result of a fall at his home that evening, and he subsequently died in his sleep.[204] His death was announced on November 10, the same day as his funeral, which was held in Montreal.[205] As was his wish, Cohen was laid to rest with a Jewish rite, in a simple pine casket, in a family plot in the Congregation Shaar Hashomayim cemetery on Mount Royal.[206][207]

Memorial services and tributes

[edit]Tributes were paid by numerous stars and political figures.[208][209][210]

Cohen died the day before Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in the U.S. presidential election. The following Saturday, Kate McKinnon reprised her role playing Clinton on Saturday Night Live in the cold open of the show, with a solo performance of Hallelujah at the piano.[211]

The city of Montreal held a tribute concert to Cohen in December 2016, titled "God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot" after a prose poem in his novel Beautiful Losers. It featured a number of musical performances and readings of Cohen's poetry.[212][213]

According to Cohen's son Adam, he had requested a small memorial service in Los Angeles and had suggested a public memorial service in Montreal.[214] A memorial for friends and family took place at the Ohr HaTorah Synagogue in Los Angeles in December 2016.[215][216] On November 6, 2017, the eve of the first anniversary of Cohen's death, the Cohen family organized a memorial concert titled "Tower of Song" at the Bell Centre in Montreal. The event included performances by k.d. lang, Elvis Costello, Feist, Adam Cohen, Patrick Watson, Sting, Damien Rice, Courtney Love, The Lumineers, Lana Del Rey and others.[217][218] Additionally, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau and his wife Sophie Grégoire Trudeau spoke about their personal connection with Cohen's music.[219]

Art and science commemorations

[edit]After Cohen's death, two murals were created in Montreal the following summer. Artist Kevin Ledo painted a nine-story portrait of him near Cohen's home on Plateau Mont-Royal. Montreal artist Gene Pendon and L.A. artist El Mec painted a 20-story fedora-clad likeness on Crescent Street.[220]

An interactive exhibit dedicated to the life and career of Leonard Cohen opened on November 9, 2017, at Montreal's contemporary art museum (MAC) titled "Leonard Cohen: Une Brèche en Toute Chose / A Crack in Everything" and ran until April 9, 2018.[221][222] The exhibit had been in the works for several years prior to Cohen's death,[223] as part of the official program of Montreal's 375th anniversary celebrations. After breaking the museum's attendance record in its five-month run,[224][225] the exhibit embarked on an international tour, opening in New York City at the Jewish Museum in April 2019.[226]

A bronze statue of Cohen was unveiled in Vilnius, capital of Lithuania, on August 31, 2019.[227]

Cohen is commemorated in the name of two species, both described in 2021. Loxosceles coheni, a species of recluse spiders from Iran, was described by arachnologists Alireza Zamani, Omid Mirshamsi and Yuri M. Marusik. Cervellaea coheni, a species of weevils from South Africa, was described by entomologists Massimo Meregalli and Roman Borovec.[228][229][230]

The television series So Long, Marianne, coproduced by Norway's NRK and Canada's Crave, is based on Cohen's relationship with Marianne Ihlen. It is slated to star Thea Sofie Loch Næss as Ihlen and Alex Wolff as Cohen.[231]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]All albums released on Columbia Records.

- Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967)

- Songs from a Room (1969)

- Songs of Love and Hate (1971)

- New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974)

- Death of a Ladies' Man (1977)

- Recent Songs (1979)

- Various Positions (1984)

- I'm Your Man (1988)

- The Future (1992)

- Ten New Songs (2001)

- Dear Heather (2004)

- Old Ideas (2012)

- Popular Problems (2014)

- You Want It Darker (2016)

- Thanks for the Dance (2019)

Bibliography

[edit]Collections

[edit]- Cohen, Leonard (1956). Let Us Compare Mythologies. [McGill Poetry Series]. Drawings by Freda Guttman. Montreal: Contact Press.

- The Spice-Box of Earth. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1961.[232]

- Flowers for Hitler. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1964.[232]

- Parasites of Heaven. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1966.[232]

- Selected Poems 1956–1968. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1968.[232]

- The Energy of Slaves. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1972. ISBN 0-7710-2204-2 ISBN 0-7710-2203-4 New York: Viking, 1973.[232]

- Death of a Lady's Man. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1978. ISBN 0-7710-2177-1 London, New York: Viking, Penguin, 1979.[232] – reissued 2010

- Book of Mercy. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1984.[232] – reissued 2010

- Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs. London, New York, Toronto: Cape, Pantheon, McClelland & Stewart, 1993.[232] ISBN 0-7710-2230-1

- Book of Longing. London, New York, Toronto: Penguin, Ecco, McClelland & Stewart, 2006.[232] (poetry, prose, drawings) ISBN 978-0-7710-2234-0

- The Lyrics of Leonard Cohen. London: Omnibus Press, 2009.[232] ISBN 0-7119-7141-2

- Poems and Songs. New York: Random House (Everyman's Library Pocket Poets), 2011.

- Fifteen Poems. New York: Everyman's Library/Random House, 2012. (eBook)

- The Flame. London, New York, Toronto: Penguin, McClelland & Stewart, 2018. (poetry, prose, drawings, journal entries)

Novels

[edit]- The Favorite Game. London, New York, Toronto: Secker & Warburg, Viking P, McClelland & Stewart, 1963.[232] Reissued as The Favourite Game. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart [New Canadian Library], 1994. ISBN 978-0-7710-9954-0

- Beautiful Losers. New York, Toronto: Viking Press, McClelland & Stewart, 1966. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart [New Canadian Library], 1991. ISBN 978-0-7710-9875-8 McClelland & Stewart [Emblem], 2003.[232] ISBN 978-0-7710-2200-5

- A Ballet of Lepers: A Novel and Stories. McClelland & Stewart, 2022. ISBN 9780771018145.

Filmography

[edit]- Ladies and Gentlemen... Mr. Leonard Cohen (1965) – documentary co-directed by Don Owen and Donald Brittain

- Angel (1966), actor – experimental animated short directed by Derek May

- Poen (1967), narrator – short film featuring four readings from his novel Beautiful Losers[233]

- The Ernie Game (1967), singer – feature film directed by Don Owen[234]

- Leonard Cohen: Bird on a Wire (1974) – documentary directed by Tony Palmer during Cohen's 1972 European tour. The film premiered in 1974 at the Rainbow Theatre in Cohen's cut;[235][236] a restored director's cut from footage discovered in 2009 was released on DVD in 2010[237] and re-released theatrically in 2017.[238]

- Song of Leonard Cohen (1980) – documentary directed by Harry Rasky for CBC filmed during Cohen's 1979 European tour. Rasky also wrote a book about the film: The Song of Leonard Cohen.

- I Am a Hotel (1983), actor, writer, produced – made for TV short musical film, directed by Allan F. Nicholls.[239] Golden Rose Award in Montreux, Switzerland.

- Night Magic (1985), lyricist, screenplay – film musical

- Miami Vice (1986), actor – S2E17, episode "French Twist"[240]

- Songs from the Life of Leonard Cohen (1988) – full-length concert of Royal Albert Hall 1988 performance intercut with interview footage. Produced by the BBC and CMV Enterprises. Released in VHS PAL and NTSC tapes and on laser-disc.

- The Tibetan Book of the Dead Part I: A Way of Life; The Tibetan Book of the Dead Part II: The Great Liberation (1994), narrator – documentary on Bardo Thodol directed by Yukari Hayashi. Released on DVD in 2004.

- Message to Love (1995) – concert documentary on the Isle of Wight Festival 1970 including a live performance of his song Suzanne.

- Spring 96. Leonard Cohen Portrait (1996) – documentary directed by Armelle Brusq shot at the Mount Baldy Zen Center. Released as home video by SMV Enterprises in VHS and DVD.

- The Favourite Game (2003) - Canadian film adaptation of the novel directed by Bernar Hebert

- Leonard Cohen: I'm Your Man (2005) – documentary and concert film directed by Lian Lunson

- Leonard Cohen. Under Review 1934-1977 (2007) and Leonard Cohen. Under Review 1978-2006 (2008) – documentary interviews with "an independent critical analysis". DVDs released by MVD Entertainment Group in the US and by Chrome Dreams Companies in the UK. First re-released as The Early Years; the second as After the Gold Rush; both re-released as Leonard Cohen. Complete Review (2012, 151 mins) and re-cut as Lonesome Heroes (110 mins). Unauthorised.

- Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love (2019) – documentary directed by Nick Broomfield. Unauthorised.

- Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song (2021) – documentary directed by Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine

Awards and nominations

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Although Hammond was originally supposed to produce the record, he was ill and was replaced by the producer John Simon.[12] Simon and Cohen clashed over instrumentation and mixing; Cohen wanted the album to have a sparse sound, while Simon felt the songs could benefit from arrangements that included strings and horns. According to biographer Ira Nadel, although Cohen was able to make changes to the mix, some of Simon's additions "couldn't be removed from the four-track master tape."[12]

- ^ The tour was filmed under the title Bird on a Wire, released in 2010.[46] Both tours were represented on the Live Songs LP. Leonard Cohen Live at the Isle of Wight 1970, released in 2009.

- ^ The recording of the album was fraught with difficulty; Spector reportedly mixed the album in secret studio sessions, and Cohen said Spector once threatened him with a crossbow. Cohen thought the end result "grotesque",[56] but also "semi-virtuous."[57]

- ^ Lissauer produced Cohen's next record Various Positions, which was released in December 1984 (and in January and February 1985 in various European countries). The LP included "Dance Me to the End of Love", which was promoted by Cohen's first video clip, directed by French photographer Dominique Issermann, and the frequently covered "Hallelujah".

- ^ Columbia declined to release the album in the United States, where it was pressed in small number of copies by the independent Passport Records. Anjani Thomas, who would become Cohen's partner, and a regular member of Cohen's recording team, joined his touring band.

- ^ During the 1980s, almost all of Cohen's songs were performed in the Polish language by Maciej Zembaty.[64]

- ^ The album, self-produced by Cohen, was promoted by black-and-white video shot by Dominique Issermann at the beach of Normandy.

- ^ The tour gave the basic structure to typical Cohen's three-hour, two-act concert, which he used in his tours in 1993, 2008–2010, and 2012. The selection of performances from the late 1980s was released in 1994 on Cohen Live.

- ^ Statistics from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA); the Canadian Recording Industry Association; the Australian Recording Industry Association; and the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry show more than five million copies of the song sold prior to late 2008 on compact disc. It has been the subject of a BBC Radio documentary and been featured in the soundtracks of numerous films and television programs.[72]

- ^ The album includes a recent musical setting of Cohen's "As the mist leaves no scar", a poem originally published in The Spice-Box of Earth in 1961 and adapted by Phil Spector as "True Love Leaves No Traces" on Death of a Ladies' Man album. Blue Alert also included Anjani's own version of "Nightingale", performed by her and Cohen on his Dear Heather, as well the country song "Never Got to Love You", apparently made after an early demo version of Cohen's own 1992 song "Closing Time". During the 2010 tour, Cohen was closing his live shows with the performance of "Closing Time" that included the recitation of verses from "Never Got to Love You". The title song, "Blue Alert", and "Half the Perfect World" were covered by Madeleine Peyroux on her 2006 album Half the Perfect World.[84]

- ^ In 2007, US. District Judge Lewis T. Babcock dismissed a claim by Cohen for more than US$4.5 million against Colorado investment firm Agile Group, and in 2008 he dismissed a defamation suit that Agile Group filed against Cohen.[94] Cohen was under new management from April 2005. In March 2012, Sylvie Simmons notes that Lynch was arrested in Los Angeles for "violating a permanent protective order that forbade her from contacting Leonard, which she had ignored repeatedly. On April 13, the jury found her guilty on all charges. On April 18 she was sentenced to eighteen months in prison and five years probation."[89] Cohen told that court, "It gives me no pleasure to see my onetime friend shackled to a chair in a court of law, her considerable gifts bent to the services of darkness, deceit, and revenge. It is my prayer that Ms. Lynch will take refuge in the wisdom of her religion, that a spirit of understanding will convert her heart from hatred to remorse, from anger to kindness, from the deadly intoxication of revenge to the lowly practices of self-reform."[95][96] In May 2016, United States District Judge Stephen Victor Wilson ordered the dismissal of Lynch's "RICO" suit against Leonard Cohen and his lawyers Robert Kory and Michelle Rice of Kory & Rice, LLP as "legally and/or factually patently frivolous."[97] On December 6, 2016, a 16-count misdemeanor complaint against Lynch, alleging violations of the protective orders entered on behalf of Leonard Cohen and his attorneys Kory and Rice, was filed.[98] At a preliminary hearing, further counts of alleged violations were added. Lynch entered a plea of not guilty to 31 counts of violating the protective orders. Lynch's pretrial hearing is scheduled for September 8, 2017.[99]

- ^ Simon Sweetman in The Dominion Post (Wellington) of January 21 wrote "It is hard work having to put this concert in to words so I'll just say something I have never said in a review before and will never say again: this was the best show I have ever seen."The Sydney Entertainment Centre show on January 28 sold out rapidly, which motivated promoters to announce a second show at the venue. The first performance was well-received, and the audience of 12,000 responded with five standing ovations. In response to hearing about the devastation to the Yarra Valley region of Victoria in Australia, Cohen donated $200,000 to the Victorian Bushfire Appeal in support of those affected by the extensive Black Saturday bushfires that razed the area just weeks after his performance at the Rochford Winery in the A Day on the Green concert.[109] Melbourne's Herald Sun newspaper reported: "Tour promoter Frontier Touring said $200,000 would be donated on behalf of Cohen, fellow performer Paul Kelly and Frontier to aid victims of the bushfires."[110]

- ^ Amnesty International withdrew from any involvement with the concert and its proceeds.[118] Amnesty International later stated that its withdrawal was not due to the boycott but "the lack of support from Israeli and Palestinian NGOs."[119] The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) led the call for the boycott, claiming that Cohen was "intent on whitewashing Israel's colonial apartheid regime by performing in Israel."[120]

References

[edit]- ^ de Melo, Jessica (December 11, 2009). "Leonard Cohen to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award at 2010 Grammys". Spinner Canada. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. January 1, 2023. Archived from the original on January 1, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "Masha Cohen". Geni.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018.

- ^ Publications, Europa (2004). The International Who's Who. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-85743-217-6. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- ^ Cohen, Leonard (May 24, 1985). "The Midday Show With Ray Martin". ABC (Interview). Interviewed by Ray Martin. Sydney. Archived from the original on February 24, 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

My – my mother was from Lithuania which was a part of Poland and my great-grandfather came over from Poland to Canada.

- ^ "Leonard Cohen Biography". AskMen. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ Sylvie Simmons, 2012, I'm Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen, p. 7.

- ^ "Nathan Bernard Cohen". Geni.com. December 1891. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018.

- ^ Woods, Allan; Brait, Ellen (November 11, 2016). "Leonard Cohen buried quietly on Thursday in Montreal". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016.

- ^ Williams, P. (n.d.) Leonard Cohen: The Romantic in a Ragpicker's Trade Archived September 19, 2012, at archive.today

- ^ "Inductee: Leonard Cohen – Into the consciousness – Hour Community". Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nadel, Ira B. Various Position: A Life of Leonard Cohen. Pantheon Books: New York, 1996.

- ^ AmericaSings (November 12, 2016). "Leonard Cohen, "Joan of Arc", Norway 1988". Archived from the original on July 21, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Wyatt, Nelson (March 11, 2012), "Celine Dion: Montreal's Schwartz's will go on", The Chronicle Herald, archived from the original on May 14, 2013

- ^ a b Langlois, Christine (October 2009), First We Take The Main (PDF), Reader's Digest, archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2013

- ^ Sax, David (2009), "Late Night Noshing", Save the Deli, archived from the original on September 7, 2012

- ^ Biography of Leonard Cohen Archived October 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

- ^ a b Simmons, Sylvie. I'm Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen. NY: HarperCollins, 2012.

- ^ Adria, Marco, "Chapter and Verse: Leonard Cohen", Music of Our Times: Eight Canadian Singer-Songwriters (Toronto: Lorimer, 1990), p. 28.

- ^ Nadel, Ira Bruce (2007). Various Positions: A Life of Leonard Cohen. Toronto: Random House. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-292-71732-9.

- ^ "A Ballet of Lepers by Leonard Cohen review – violent literary beginnings". The Guardian. October 1, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "'I want to write songs': Leonard Cohen gave up hosting CBC TV show to be songwriter". Archived from the original on November 13, 2016.

- ^ Simmons, Sylvie. I'm Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen. New York: HarperCollins, 2012.

- ^ "The Leonard Cohen Files". Leonardcohenfiles.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Blackening Pages". Leonardcohenfiles.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ Iyer, Pico (October 22, 2001). "Listening to Leonard Cohen | Utne Reader". Utne.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ "Laureates – Princess of Asturias Awards – The Princess of Asturias Foundation". The Princess of Asturias Foundation. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Warhol, Andy: Popism. Orlando: Harcourt Press, 1980.

- ^ a b "Closing Time: The Canadian arts community remembers Leonard Cohen" Archived December 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Globe and Mail, Canada, November 11, 2016

- ^ a b Beta Hi-Fi Archive (July 23, 2009). "JUDY COLLINS – Interview about Leonard Cohen, "Suzanne"". Archived from the original on April 11, 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ The Autobiography of Judy Collins (Pages 145–147 of the hardbound edition or 144–146 of the paperback edition).

- ^ Beta Hi-Fi Archive (July 6, 2013). "Judy Collins & Leonard Cohen – "Hey, That's No Way To Say Goodbye" 1976". Archived from the original on November 14, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Beta Hi-Fi Archive (July 6, 2013). "JUDY COLLINS & LEONARD COHEN – "Suzanne" 1976". Archived from the original on March 23, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ AmericaSings (November 11, 2016). "Leonard Cohen forgets the lyrics!". Archived from the original on August 7, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Céline Allais (May 1, 2009). "Joan Baez – Suzanne". Archived from the original on February 1, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Remnick, David (October 17, 2016). "Leonard Cohen Makes It Darker". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ "25 best Canadian debut albums ever" Archived September 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. CBC Music, June 16, 2017.

- ^ "A Fabulous Creation", David Hepworth, Bantam Press (March 21, 2019), ISBN 0593077636