Ewe Unification Movement

The Ewe Unification Movement (French: Mouvement d'unification Ewe) was a series of west African ethno-nationalist efforts which sought the unification of the Ewe peoples spread across what are now modern Ghana and Togo. It emerged as a direct political goal around 1945 under the colonial mandate of French Togoland,[1] however the ideal of unifying the group has been an identifiable sentiment present amongst the ethnicity's leadership and wider population ever since their initial colonial partitions by the British and German Empires from 1874 to 1884.[2][3] While there have been many efforts to bring about unification, none have ultimately been successful due to both the platform itself often being a secondary concern for political leadership, or inter/intrastate conflicts overshadowing them.

Background

[edit]A loose conception of an Ewe identity has existed through a shared origin myth surrounding the Togolese town of Notsé and a subsequent exodus from it due to the tyranny of its king Agokoli,[4] but historical evidence for this specific tradition's basis in reality is lacking.[5] The more accepted version of their history follows the group's 1600s westward migration from the town of Ketu around the Benin-Nigeria border after pressures began to mount from the neighboring Yoruba.[2][4][6] After settling in their current territories around the Volta Region, the Ewe were fragmented into a menagerie of chiefdoms and villages called dukowo, though they sometimes consolidated into military alliances against external threats such as the Akwamu in 1833, or Ashanti in 1868.[5] While no fully unified Ewe character had consolidated at this point, because conflicts between different dukowo were common — such as those between the Anlo and Gen in the 1680s[7] — Ewe nationalists eventually took advantage of the aforementioned shared traditions and moments of cooperation during the colonial period.[5]

Early colonialism

[edit]

Ewe interaction with Europeans prior to colonization was primarily confined to trade along the Gold & Slave coasts and mouth of the Volta River.[8] However, this changed once the British Empire began asserting itself in the region to establish its own west African colonial claims from 1850 to 1874.[3] In accordance with this new colonial rush, the German Empire, too, established its own holdings along the coast in 1884, thus dividing the Ewe between two colonial powers.[3]

It was with this division that the Ewe identity began to become politically salient, as many within their leadership protested the consequent restriction of movement through what they had begun to see as a unified Ewe territory.[3][9]

German missionaries

[edit]

Under German colonial rule, a common governing ethos was that of divide et impera, which sought to exacerbate their various colonial subjects' cultural identities against each other to prevent larger political units from forming against their imperial hegemony.[10] This manifested itself in German Togoland with the pitting of the Ewe peoples against other more allegedly barbaric groups, like the Ashanti, by German Protestant priests from the Norddeutsche Missionsgesellschaft.[10] Under the ethos, these priests translated the Protestant Bible into a standardized Ewe language, and utilized it and the resulting linguistic studies to consolidate a shared Ewe identity based around a common language to loosely unify their disparate polities further.[11]

World War I and late colonialism

[edit]During the first World War, the Ewe in the British Gold Coast Colony actively supported their overlords in the Entente, while those in Togoland mostly withheld loyalty from their own colonizer, in the hopes that the defeat of the Germans would unify the Ewe peoples under one government.[12][13]

When the war ended, the British and French divided Togoland between themselves. This ultimately only served as a partial unification of some Ewe — for while many in the west now found themselves essentially unified under two British colonial administrations, the rest in the east were placed under a French mandate.[14] This tripartite division between the Gold Coast Colony and British & French Togoland left many Ewe leaders dissatisfied, but voicing their concerns ultimately, having been brought by the Congress of British West Africa to British administrators for consideration in 1920, yielded no change.[15]

Unification movements

[edit]

In Togo

[edit]Around 1945, various members of Ewe and wider Togolese leadership began the construction of political organizations which sought to decolonize French Togo. These developed as the Comité de l'Unité Togolaise, led by Sylvanus Olympio, and the Mouvement la Jeunesse Togolaise. Both possessed political platforms that included the reunification of the separate British western and French eastern Togolands, and, for the Ewe, this implied a reunification of their eastern populations.[1][16][17][18]

After the Comité de l'Unité Togolaise began gaining power in the territory's Representative Assembly in 1946, French administrators, from 1950 onward, attempted to subvert the movement's gains by arresting or restricting its leadership, limiting its legal political status, and sowing rivalries with other Togolese political parties.[19] Despite these efforts, however, the French administration began to lose favor with the Togolese population, and, coupled with mounting pressures from the neighboring and ever more autonomous British colonies, began a process of autonomy granting, which eventually altogether ended their trusteeship over the territory in 1956, giving Togo independence, and placing Sylvanus Olympio in power as Togo's first president.[20]

Sylvanus Olympio's eventual usurper, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, did not focus on his predecessor's greater Togoland claims in the initial period of his leadership.[21] However, after internal pressures of Ewe separatism in Ghana resurfaced, Gnassingbé Eyadéma's regime reaffirmed the claims and publicly lauded the Ewe's goals.[22][21] However, this reorientation towards irredentism was seemingly only rhetorical, as Gnassingbé Eyadéma's government was in practice cooperative with Ghana's efforts at suppressing the separatists due to Togo's heavy reliance on Ghanaian hydroelectric capacities.[23]

In Ghana

[edit]Like in Togo, political organizations such as the All Ewe Conference pursued the Ewe unification platform in the British colonies.[1][17] Just the same, the British were antagonistic to the idea of granting them any special autonomy.[16]

In 1956, the British conducted a plebiscite in their Togoland mandate which resulted in the unification of it to the Gold Coast Colony. This drew opposition from many Ewe under the new administration, as while most of them supported the results, some instead still preferred to be reincorporated into a united Togoland — with this portion having been the primary support behind another unification party called the Togoland Congress, featuring members such as Dr Raphael Armattoe.[24][25][26]

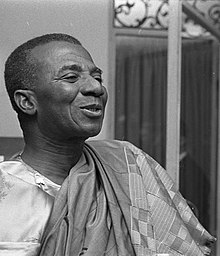

After Ghanaian independence, the country's first president, Kwame Nkrumah, supported Ewe unification by proxy, because he required their favor for his goal of a Ghanaian-led unification with Togo, which would consequently place the Ewe under one country's administration— though he was ultimately still opposed to a fully independent Ewe state.[22][27] This created tensions with Sylvanus Olympio, as both leaders, thereafter, had claims over the other's territories, and this resulted in a more restrictive border between the two newly independent countries.[28] This tension briefly subsided with the rise of Gnassingbé Eyadéma to power in Togo, because his regime was more cooperative with Ghana — at least until the 1970s, when he began agitating for Ewe separatism and suggesting border readjustments.[29][30][31]

Tolimo

[edit]

In 1976, an Ewe-led movement formed in Ghana's former British Togoland provinces that sought secession and reunification with Togo called the National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland, or Tolimo Movement, which stemmed from the Togoland Congress. While its secessionist sentiments developed originally due to the 1956 plebiscite, this iteration was spurred by alleged Ewe repression by Kwame Nkrumah due to the more restrictive border with Togo, along with the generally poorer conditions which were common amongst the Ghanaian Ewe populations during the time.[21][22][23] It had support from Gnassingbé Eyadéma in Togo, though this was only an expressed public support, and ultimately nothing substantive.[23]

Following an attempted coup in 1975, which the Ewe were implicated in as having been its alleged primary backers, the Ghanaian government cracked down on Tolimo with a plan, Operation Counterpoint, that aimed to restrict cross-border Ewe travel.[30] The organization was eventually outlawed officially in 1976.[31]

This separatist movement was largely repressed especially after Jerry Rawlings seized the reins of power.[32]

While separatist groups do still exist, most of their independence efforts have been effectively stunted by the Ghanaian government.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Amenumey, D. E. K. (1975). "The General Elections in the 'Autonomous Republic of Togo', April 1958: Background and Interpretation". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 16 (1): 48. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406580.

- ^ a b Amenumey, D. E. K. (1969). "The Pre-1947 Background to the Ewe Unification Question: a Preliminary Sketch". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 10: 65–85. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406350.

- ^ a b c d Amenumey, D. E. K. (1969). "The Pre-1947 Background to the Ewe Unification Question: a Preliminary Sketch". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 10: 66–67. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406350.

- ^ a b Meyer, Birgit (2002). "Christianity and the Ewe Nation: German Pietist Missionaries, Ewe Converts and the Politics of Culture". Journal of Religion in Africa. 32 (2): 169–170. doi:10.1163/157006602320292906. ISSN 0022-4200. JSTOR 1581760.

- ^ a b c Nugent, Paul (2008). "Putting the History Back into Ethnicity: Enslavement, Religion, and Cultural Brokerage in the Construction of Mandinka/Jola and Ewe/Agotime Identities in West Africa, c. 1650-1930" (PDF). Comparative Studies in Society and History. 50 (4): 935. doi:10.1017/S001041750800039X. hdl:20.500.11820/d25ddd7d-d41a-4994-bc6d-855e39f12342. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 27563713. S2CID 145235778.

- ^ Shoup, John A. III (2011). Ethnic groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7. OCLC 730114530.

- ^ Amenumey, D. E. K. (1969). "The Pre-1947 Background to the Ewe Unification Question: a Preliminary Sketch". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 10: 66. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406350.

- ^ Nugent, Paul (2008). "Putting the History Back into Ethnicity: Enslavement, Religion, and Cultural Brokerage in the Construction of Mandinka/Jola and Ewe/Agotime Identities in West Africa, c. 1650-1930" (PDF). Comparative Studies in Society and History. 50 (4): 932–933. doi:10.1017/s001041750800039x. hdl:20.500.11820/d25ddd7d-d41a-4994-bc6d-855e39f12342. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 27563713. S2CID 145235778.

- ^ Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 578–579. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ a b Meyer, Birgit (2002). "Christianity and the Ewe Nation: German Pietist Missionaries, Ewe Converts and the Politics of Culture". Journal of Religion in Africa. 32 (2): 170–171. doi:10.1163/157006602320292906. ISSN 0022-4200. JSTOR 1581760.

- ^ Meyer, Birgit (2002). "Christianity and the Ewe Nation: German Pietist Missionaries, Ewe Converts and the Politics of Culture". Journal of Religion in Africa. 32 (2): 176–178. doi:10.1163/157006602320292906. ISSN 0022-4200. JSTOR 1581760.

- ^ Amenumey, D. E. K. (1969). "The Pre-1947 Background to the Ewe Unification Question: a Preliminary Sketch". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 10: 68. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406350.

- ^ Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 579–580. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ Amenumey, D. E. K. (1969). "The Pre-1947 Background to the Ewe Unification Question: a Preliminary Sketch". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 10: 69. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406350.

- ^ Amenumey, D. E. K. (1969). "The Pre-1947 Background to the Ewe Unification Question: a Preliminary Sketch". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 10: 70. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406350.

- ^ a b Amenumey, D. E. K. (1975). "The General Elections in the 'Autonomous Republic of Togo', April 1958: Background and Interpretation". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 16 (1): 49. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406580.

- ^ a b Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 581. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ United Nations, High Commissioner for Refugees. "UN General Assembly, The Ewe and Togoland Unification Problem, 20 December 1952, A/RES/652". Refworld.

- ^ Amenumey, D. E. K. (1975). "The General Elections in the 'Autonomous Republic of Togo', April 1958: Background and Interpretation". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 16 (1): 50–53. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406580.

- ^ Amenumey, D. E. K. (1975). "The General Elections in the 'Autonomous Republic of Togo', April 1958: Background and Interpretation". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 16 (1): 55–56. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406580.

- ^ a b c Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 583–585. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ a b c McLaughlin, James L.; Owusu-Ansah, David (1994). Ghana: A Case Study (PDF). p. 238.

- ^ a b c McLaughlin, James L.; Owusu-Ansah, David (1994). Ghana: A Case Study (PDF). pp. 85–86.

- ^ Mapp, Roberta E. (1972). "Cross-National Dimensions of Ethnocentrism". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 6 (1): 81. doi:10.2307/484153. ISSN 0008-3968. JSTOR 484153.

- ^ Brown, David (1982). "Who Are the Tribalists? Social Pluralism and Political Ideology in Ghana". African Affairs. 81 (322): 50. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097404. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 721504.

- ^ McLaughlin, James L.; Owusu-Ansah, David (1994). Ghana: A Country Study (PDF). p. 30.

- ^ Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 575–609. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 583. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 586. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ a b Brown, David (1980). "Borderline Politics in Ghana: The National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (4): 591. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00014750. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160799.

- ^ a b McLaughlin, James L.; Owusu-Ansah, David (1994). Ghana: A Case Study (PDF). p. 258.

- ^ Chazan, Naomi (1982). "Ethnicity and Politics in Ghana". Political Science Quarterly. 97 (3): 474–484. doi:10.2307/2149995. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2149995.

- ^ "We have no militia - Western Togoland independence 'fighters'". Citi Newsroom. 2019-05-07. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch