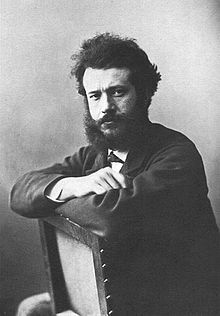

Félix Bracquemond

Félix Henri Bracquemond (French pronunciation: [feliks ɑ̃ʁi bʁakmɔ̃]; 22 May 1833 – 29 October 1914) was a French painter, etcher, and printmaker. He played a key role in the revival of printmaking, encouraging artists such as Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro to use this technique.[1]

Unusually for a prominent artist of this period, he also designed pottery for a number of French factories, in an innovative style that marks the beginning of Japonisme in France.

He was the husband of the Impressionist painter Marie Bracquemond.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Félix Bracquemond was born in Paris. He was trained in early youth as a trade lithographer, until Joseph Guichard, a pupil of Ingres, took him to his studio.[1] His portrait of his grandmother, painted by him at the age of nineteen, attracted Théophile Gautier's attention at the Salon.[2]

Engraver

[edit]His work in painting is rather limited. It includes mostly portraits (including that of Dr. Horace Montegre, and of Paul Meurice). Painting interested him less than engraving. He drew most of his technical knowledge from the Encyclopédie by Diderot and d'Alembert and he worked as a self-taught artist for a long time. In 1856, Edmond de Goncourt became close friends with Bracquemond, and they both shared a love of Japanese art, the engraver having been the first to discover an album by Hokusai.[2]

He applied himself to engraving and etching about 1853, and played a leading and brilliant part in the revival of the etcher's art in France. Altogether he produced over eight hundred plates, comprising portraits, landscapes, scenes of contemporary life, and bird-studies, besides numerous interpretations of other artist's paintings, especially those of Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Gustave Moreau and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.[3]

He entered the literary milieu thanks to Auguste Poulet-Malassis, publisher of Charles Baudelaire with whom Bracquemond became friends. He also befriended Théodore de Banville, Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly, Gustave Geffroy, Félix Nadar and all the elites residing in Nouvelle Athènes.[2] He also was a friend of Auguste Rodin.

In June 1862, he joined the Société des aquafortistes founded by the publisher Alfred Cadart with the help of the printer Auguste Delâtre.[4] On his advice, Jean-Baptiste Corot, Jean-François Millet, Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro began to practice engraving. He greatly helped Manet for his etchings of Olympia and L'Homme mort.

In 1888, Auguste Lepère created with Félix Bracquemond, Daniel Vierge and Tony Beltrand, the magazine L'Estampe originale, in order to interest artists and amateurs in the new processes and trends of engraving, particularly in color, and Henri Rivière worked from this date on "The Thirty Six Views of the Eiffel Tower", from 1888 to 1902.[5] In 1891, Valloton renewed the art of engraving on wood,[6] with Gauguin or Émile Bernard while Toulouse Lautrec revolutionized the art of the poster.

Friend of the Impressionists

[edit]

In 1874 Bracquemond participated in the first exhibition of Impressionist painters in the workshops of Nadar, Boulevard des Capucines, of artists that would be called the Impressionists.[7] The inauguration took place on 15 April 1874 and enjoyed a scandalous success. He presented a portrait, a frame of etchings including the portraits of Auguste Comte, Charles Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier, but also etchings after Turner, Ingres, Manet, and original etchings: Les Saules (The Willows), Le Mur (The Wall). He exhibited again with his friends in 1879.[2]

Ceramicist

[edit]In 1856, Bracquemond discovered a collection of Manga engravings by the Japanese Hokusai, typical of the pictorial genre known in Japan as Kachô-ga, depicting flowers and birds with insects, crustaceans and fishes, in the workshop of his printer Auguste Delâtre, after having been used to fix a consignment of porcelain. He was seduced by this theme that made him the initiator of the vogue of Japonisme in France which seized the decorative arts during the second half of the 19th century.[8][9]

In 1860, he returned first to the workshop of the ceramist Théodore Deck, then to the earthenware merchant Eugène Rousseau in Paris. The latter commissioned him the motifs for a table service, for a project destined for the Universal Exhibition of 1867. Bracquemond then proposed a model which appropriated the themes of the Kachô-ga, drawn and engraved by himself. For the first time a European artist directly copied a Japanese artist, reproducing the animal figures of the Hokusai Manga. In 1867, Bracquemond was also one of the nine members of the "Société du Jing-lar" with Henri Fantin-Latour, Carolus Duran and the ceramist Marc-Louis Solon, who met monthly in Sèvres for a Japanese dinner, to which this service would have been destined.

Eugène Rousseau was convinced and ordered two hundred pieces to be manufactured in Creil-Montereau faience. Bracquemond made the etchings and the engraved planks used by the manufacture. The proofs were cut and put on the clay to receive the decoration. In the oven, the heat made the paper disappear, leaving only the imprint of the drawing. Then it was painted over and the piece was placed in the large oven.

Presented for the first time at the Universal Exhibition of 1867, this service was a great success. It was in the third group "furniture and other objects for the home", Class 17 "porcelain, earthenware, and luxury pottery" no. 58, installed on Louis XIII shelves in old oak with velvet stands. Above the counter, the name Rousseau is enameled with fire on a plaque. The jury awarded him a bronze medal (because Rousseau was merchant and not manufacturer). The gold medal was awarded to the manufacturers Lebeuf and Milliet. The service also boasted two novelties: the first was that everyone was free to compose his service according to his tastes and personal use. Rousseau suggested "the barnyard for meat, Crustaceans for fish and flowers for dessert." The second was that the service was adapted to wider circles: "for its sumptuousness to the bourgeoisie, and for its aspect serving as a hunt for the nobility."

The service was then completed (teacups, coffee, etc.) and the manufacture left to the Creil and Montereau factory. Barluet, Lebeuf's successor, re-edited it in the early 1880s. In 1885, Eugène Rousseau sold his business to Ernest-Baptiste Leveillé, who continued to publish the service under his own brand. Many reissues or variants followed. Among them, that of the Manufacture Jules Vieillard in Bordeaux (late 19th century), that of the Crystal Stairs (early 20th century), or even of the faience of Gien The large birds still in reissue. It can also be noted that many pieces of this service are now preserved in various French national museums (Musée d'Orsay, Musée national Adrien Dubouché, etc.).[11]

Each element of the service, inspired by Japanese prints, was decorated with a different motif. The decoration treats and associates a multitude of birds, fishes, and crustaceans, always leaving room for plants and insects. The decor is often presented as a trilogy. The butterfly meets a cock at the turn of a branch, a dragonfly meets a carp at the bend of a water lily.

Many artists of the time celebrated the poetry of this service and praised its exceptional decor. Mallarmé notably, noted a "visible decadence" since the Restoration in the French furniture, testifies to his appeal for this service. He lingered on ceramics for a special praise of Rousseau, whom he defended against his English imitators: "I had refused all allusions necessarily too briefly to this admirable and unique service, decorated by Bracquemond with Japanese motifs borrowed from the poultry yard and the fish ponds, the most beautiful crockery I have ever known. Each piece, the plates even, wants its special description. I am satisfied, one last time, to claim the priority of Parisian work, picturesque and spiritual on British plagiarism..." . Mallarmé quoted Deck, Collinot and Rousseau, who had "totally renewed French ceramics": "I should particularly mention, as a translation of the high Japanese charm made by a very French spirit, the table service asked, boldly, for the master Aquafortiste Bracquemond: where struts, enhanced with joyous colors, the ordinary hosts of the poultry yard and fish ponds." Mallarmé himself possessed pieces of the service, published during the period 1866–1875.

Félix Bracquemond also worked for the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres in 1870, giving his works a new orientation that preludes the Art Nouveau modern style]]. He also accepted the position of artistic director of the Parisian studio of the firm Charles Haviland of Limoges.

Other work and later life

[edit]A close friend of Édouard Manet, James McNeill Whistler, and Henri Fantin-Latour, he is represented in the latter's paintings, Hommage à Delacroix, 1864, preserved in Paris at the Musée d'Orsay[12] and Toast with the Truth of 1865, destroyed by the artist.[13]

He married Marie Quivoron, a painter known as Marie Bracquemond, on 5 August 1869, in Paris.[14] Their son, Pierre, claimed that Felix was jealous and critical of Marie's work. His beratement caused Marie to cease painting.

He is also the author of a book entitled Du dessin et la couleur, published in 1886, very much appreciated by Vincent van Gogh,[15] and a study on woodcutting and lithography. His best engravings are devoted either to landscapes or to animals: Reeds and teals (1882), Les Hirondelles (1882), Les Mouettes (1888).

He was honored as an Officer of the Legion of Honor in 1889.[3]

Gabriel P. Weisberg called him the "molder of artistic taste in his time".[16] Indeed, it was he who recognised the beauty of the Hokusai woodcuts used as packing around a shipment of Japanese china, a discovery which helped change the look of late 19th-century art.[17]

He died in Sèvres.

- 1872–80

- Alfred de Curzon, 1850s

- La Mer, 1850–1914

- Portrait of Ferdinand Lesseps, 1850–1914

- Frontispiece for Oeuvres Nouvelles de Champfleury (after Courbet), 1860–98

- Frontispiece for an Album of the Société des Aquafortistes, 1865

- Frontispiece for L'Illustration Nouvelle, 1867

- La statue de la Résistance par Falguière, 1870

- Nôtre Dame, Paris, 1870

- Edwin Edwards, 1872

- The Locomotive (after Turner), 1873

- Death Mask of

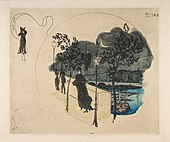

Auguste Blanqui, 1881 - Les Hirondelles,

ca. 1882 - Portrait of

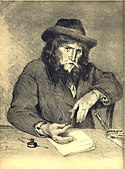

Edmond de Goncourt, 1882 - Portrait of Auguste

Poulet-Malassis, 1884 - The Monkey and the Cat, from the Fables of La Fontaine, 1886

- The Gallic Cock--Long Live the Czar!, 1893

- Woman's Head, from L'Estampe Moderne, 1897–99

- Portrait of

Léon Cladel, 1905 - Portrait of

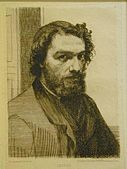

Alphonse Legros

References

[edit]- ^ a b Monneret 1987, p. 74

- ^ a b c d Monneret 1987, p. 75

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bracquemond, Félix". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 369.

- ^ Valérie Sueur, « L’éditeur Alfred Cadart (1828-1875) et le renouveau de l’eau-forte originale », in Europeana Newspapers, avril 2013 — lire sur Gallica Archived 2017-08-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "L'anti-musée par Yann André Gourvennec, " Les Trente-six vues de la Tour Eiffel " de Henri Rivière". antimuseum.online.fr (in French).

- ^ The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints, Colta Feller Ives, 1980, p. 18 à 20, Metropolitan Museum of Art, site books.google.fr

- ^ Carine, Girac-Marinier (2011). "De Monet à Turner". In Larousse (ed.). Découvrir les Impressionnistes (in French). Paris. p. 92. ISBN 978-2-03-586373-7. OCLC 866801730.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), p. 26 (lire en ligne, accessed 4 April 2014) - ^ Gallica, Gazette des beaux-arts, 1905, pp. 142 à 143, site gallica.bnf.fr

- ^ Bibliothèques municipales de Grenoble

- ^ "Musée d'Orsay, "Art, industry and japonism : the "Rousseau" set"". Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ 68 pièces de céramique (en août 2015) sont présentées de façon détaillée dans la base Joconde.

- ^ Henri Fantin-Latour, Hommage à Delacroix, 1864 Archived 2018-10-21 at the Wayback Machine, Musée d'Orsay, site musée-Orsay.fr

- ^ Henri Fantin-Latour, Toast avec la vérité, 1865, Louvre, dessin du tableau détruit par l'artiste, site art-graphiques.Louvre.fr

- ^ Galerie de dessins de Marie Bracquemond Category:Marie Bracquemond

- ^ Monneret 1987, p. 76

- ^ Weisberg, Gabriel (September 1976). "Félix Bracquemond and the Molding of French Taste". ARTnews: 64–66.

- ^ Bouillon, Jean-Paul (1980). "Remarques sur la Japonisme de Bracquemond". Japonisme in Art, Art Symposium. Tokyo: Kodansha International: 83–108.

Works cited

[edit]- Monneret, Sophie (1987). L'Impressionnisme et son époque – Noms propres A à T (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 978-2-221-05412-3.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Félix Bracquemond at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Félix Bracquemond at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch