Quatermass and the Pit (film)

| Quatermass and the Pit | |

|---|---|

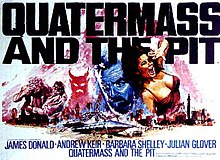

UK quad crown theatrical release poster by Tom Chantrell | |

| Directed by | Roy Ward Baker |

| Written by | Nigel Kneale |

| Based on | Quatermass and the Pit by Nigel Kneale |

| Produced by | Anthony Nelson Keys |

| Starring | James Donald Andrew Keir Barbara Shelley Julian Glover |

| Cinematography | Arthur Grant |

| Edited by | Spencer Reeve |

| Music by | Tristram Cary |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Associated British Pathé (UK) 20th Century Fox (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £275,000[1] |

Quatermass and the Pit (US title: Five Million Years to Earth) is a 1967 British science fiction horror film from Hammer Film Productions.[2] It is a sequel to the earlier Hammer films The Quatermass Xperiment and Quatermass 2. Like its predecessors, it is based on a BBC Television serial, in this case Quatermass and the Pit, written by Nigel Kneale.[3] The storyline, largely faithful to the original television production, centres on the discovery of ancient human remains buried at the site of an extension to the London Underground called Hobbs End. More shocking discoveries lead to the involvement of the space scientist Bernard Quatermass.

It was directed by Roy Ward Baker and stars Andrew Keir[3] in the title role as Professor Bernard Quatermass, replacing Brian Donlevy, who played the role in the two earlier films. James Donald, Barbara Shelley and Julian Glover appear in co-starring roles. The film opened in November 1967 to favourable reviews, and remains generally well regarded.

Plot

[edit]Workers building an extension to the London Underground at Hobbs End dig up an odd-looking skull. Palaeontologist Dr Matthew Roney identifies it as a five-million-year-old apeman, more ancient than previous finds. One of Roney's assistants uncovers part of a metallic object nearby. Believing it to be an unexploded bomb from the London blitz, they call in an army bomb disposal team.

Meanwhile, Professor Bernard Quatermass learns that his plans for the colonisation of the Moon are to be taken over by the military, with plans to establish ballistic missile bases in space. Colonel Breen is assigned to Quatermass's British Experimental Rocket Group. When the bomb disposal team call for Breen's assistance, Quatermass accompanies him to the site. When another skull is found within a chamber of the "bomb", they realise that the object itself must also be five million years old. Noting its imperviousness to heat, Quatermass suspects it is of alien origin, but Roney is certain the apemen were terrestrial.

Roney's assistant, Barbara Judd, goes to the site with Quatermass. She becomes intrigued by the name of the area, recalling that "Hob" is an old name for the Devil. A policeman mentions the legend that the bombed-out house opposite the station is haunted. All three go there to investigate. The policeman is so spooked that he has to leave. A member of the bomb disposal team witnesses a spectral apparition of Roney's apeman appearing through the object's wall. Quatermass and Barbara find historical accounts of hauntings and other spectral appearances going back centuries, coinciding with disturbances of the ground around Hobbs End.

An attempt to open a sealed chamber in the object using a Borazon drill fails. Later, however, a small hole is seen, though the drill operator, Sladden, is certain that he is not responsible for it. The hole widens to reveal the corpses of three-legged, insectoid creatures with horned heads. An examination of their physiology suggests that they came from Mars. Quatermass and Roney note the similarity between their appearance and images of the Devil, while Quatermass believes that the spaceship is the source of the spectral images and disturbances.

They reveal their findings to the press, attracting the ire of a government minister who has not sanctioned their statements. Quatermass theorises that the occupants of the spaceship came from a dying Mars. Unable to survive on Earth, they sought to preserve part of their race by creating a colony by proxy, by enhancing the intelligence of and imparting Martian faculties to the indigenous primitive hominids. Quatermass theorizes that the insectoids used medical and surgical techniques that were more advanced than those on present-day Earth. These apemen's descendants evolved into humans, retaining the vestiges of Martian influence buried in their subconscious. Breen thinks that the "alien craft" is Nazi propaganda designed to sow fear among Londoners. The minister believes Breen and decides to unveil the spaceship at a press conference.

Whilst dismantling his drill, Sladden is overcome by a psychic force and flees. His mind unleashes telekinetic energy displays, disrupting people and property. He comes to rest in a church, where Judd and Quatermass find him. Sladden had a vision of hordes of insect creatures under an alien sky. Sladden also saw himself as one of them and felt that he had to flee in fear of his life. Quatermass returns to Hobbs End, bringing a machine Roney has been working on, which taps into the primeval psyche. While trying to replicate the circumstances under which Sladden was affected, he notices that Barbara has fallen under the spaceship's influence. Using Roney's machine, he records her thoughts. Quatermass presents the recording to the minister and other officials. It shows hordes of Martians engaged in what he interprets as a genocidal race purge, to cleanse the Martian hives of all mutations. The minister and Breen dismiss the recording.

A power line later is dropped within the craft, giving it a jolt of electrical energy. The effect and range of the spaceship's influence on Londoners increases; they go on a rampage, attacking all those perceived as different, with deadly telekinetic displays of energy. Breen is drawn towards the spaceship and killed by the energy emanating from it. Quatermass falls under the alien control as well, but is snapped out of it by Roney, who is unaffected. The two realise that a small portion of the population are immune. The psychic energy intensifies, ripping up streets and buildings, while a spectral image of a Martian towers above the city, itself resembling the image of the Devil of legend. Recalling stories about how the Devil could be defeated with iron and water, Roney theorises that the Martian energy can be discharged into the earth. Quatermass prevents Barbara from stopping Roney, who climbs a building crane and swings it into the spectral image. The crane bursts into flames as it discharges the energy, killing Roney. The image and its effects on London disappear. Devastated, Quatermass and Barbara stand silently amidst London's ruins.

Cast

[edit]

- James Donald as Doctor Roney

- Andrew Keir as Professor Bernard Quatermass

- Barbara Shelley as Barbara Judd

- Julian Glover as Colonel Breen

- Edwin Richfield as Minister

- Duncan Lamont as Sladden

- Bryan Marshall as Captain Potter

- Peter Copley as Howell

- Grant Taylor as Police Sergeant Ellis

- Maurice Good as Sergeant Cleghorn

- Robert Morris as Watson

- Sheila Steafel as Journalist

- Hugh Futcher as Sapper West

- Hugh Morton as Elderly Journalist

- Thomas Heathcote as Vicar

- Noel Howlett as Abbey Librarian

- Hugh Manning as Pub Customer

- June Ellis as Blonde

- Keith Marsh as Johnson

- James Culliford as Corporal Gibson

- Bee Duffell as Miss Dobson

- Roger Avon as Electrician

- Brian Peck as Technical Officer

- John Graham as Inspector

- Charles Lamb as Newsvendor

Production

[edit]Origins

[edit]Professor Bernard Quatermass was introduced to audiences in two BBC television serials, The Quatermass Experiment (1953) and Quatermass II (1955), written by Nigel Kneale. The rights to both these serials were acquired by Hammer Film Productions, and the film adaptations – The Quatermass Xperiment and Quatermass 2, both directed by Val Guest and starring Brian Donlevy as Quatermass were released in 1955 and 1957, respectively.[4] Kneale went on to write a third Quatermass serial – Quatermass and the Pit – for the BBC, which was broadcast in December 1958 and January 1959. Once again interested in making a film adaptation, Hammer and Kneale, who had by then left the BBC and was working as a freelance screenwriter, completed a script in 1961. It was intended that Val Guest would once again direct and Brian Donlevy would reprise his role of Quatermass, with production to commence in 1963.[5] Securing financing for the new Quatermass film proved difficult. In 1957 Hammer had struck a deal with Columbia Pictures to distribute their pictures, and the companies collaborated on thirty films between 1957 and 1964.[6] Columbia, which was not interested in Quatermass, passed on the script, and the production went into limbo for several years.[7] In 1964 Kneale and Anthony Hinds submitted a revised, lower-budget script to Columbia, but the relationship between Hammer and Columbia had begun to sour and the script was again rejected.[8] In 1966 Hammer entered into a new distribution deal with Seven Arts Productions, Associated British Picture Corporation, and Twentieth Century Fox; Quatermass and the Pit finally entered production.[7]

Writing

[edit]Kneale wrote the first draft of the screenplay in 1961, but difficulties in attracting interest from American co-financiers meant the film would not go into production until 1967.[citation needed]

The screenplay is largely faithful to the television original. The plot was condensed to fit the shorter running time of the film, the main casualty being the removal of a subplot involving the journalist James Fullalove.[7] The climax was altered to make it more cinematic, with Roney using a crane to short out the Martian influence, whereas in the television version he throws a metal chain into the pit.[7] The setting for the pit was changed from a building site to the London Underground.[8] The closing scene of the television version, in which Quatermass pleads with humanity to prevent Earth becoming the "second dead planet", was also dropped, in favour of a shot of Quatermass and Judd sitting alone amid the devastation wrought by the Martian spacecraft.[9]

Casting

[edit]Andrew Keir, playing Quatermass, found making the film an unhappy experience, believing Baker had wanted Kenneth More in the role.

James Donald first came to prominence playing Theo van Gogh in Lust for Life (1956) before going on to play a string of roles in the World War II prisoner of war films The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), The Great Escape (1963) and King Rat (1965).[10][better source needed] Although not playing the title role, Donald was accorded top-billing status.[11]

Nigel Kneale had long been highly critical of Brian Donlevy's interpretation of Quatermass and lobbied for the role to be recast, arguing that enough time had passed that audiences would not resist a change of actor.[12] Several actors were considered for the part, including André Morell, who had played Quatermass in the television version of Quatermass and the Pit.[13] Morell was not interested in revisiting a role he had already played.[12] The producers eventually settled on the Scottish actor Andrew Keir, who had appeared in supporting roles in other Hammer productions, including The Pirates of Blood River (1962), The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964) and Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966).[13] Keir found the shoot an unhappy experience: he later recalled: "The director – Roy Ward Baker – didn't want me for the role. He wanted Kenneth More ... and it was a very unhappy shoot. [...] Normally I enjoy going to work every day. But for seven-and-a-half weeks it was sheer hell."[14] Roy Ward Baker denied he had wanted Kenneth More, who he felt would be "too nice" for the role,[15] saying: "I had no idea he [Keir] was unhappy while we were shooting. His performance was absolutely right in every detail and I was presenting him as the star of the picture. Perhaps I should have interfered more."[16] He reprised the role of Quatermass for BBC Radio 3 in The Quatermass Memoirs (1996), making him the only actor other than Donlevy to play the role more than once.[17]

Barbara Shelley was a regular leading lady for Hammer, having appeared in The Camp on Blood Island (1958), Shadow of the Cat (1961), The Gorgon (1964), The Secret of Blood Island (1964), Dracula: Prince of Darkness and Rasputin, the Mad Monk (1966) for them.[18][better source needed] Quatermass and the Pit was her last film for the company and she subsequently worked in television and the theatre.[19] Roy Ward Baker was particularly taken with his leading lady, telling Bizarre Magazine in 1974 that he was "mad about her in the sense of love. We used to waltz about the set together, a great love affair."[14]

Filming

[edit]By the time Quatermass and the Pit finally entered production Val Guest was occupied on Casino Royale (1967), so directing duties went instead to Roy Ward Baker.[12] Baker's first film had been The October Man (1947) and he was best known for The One That Got Away (1957) and A Night to Remember (1958).[20] Following the failure of Two Left Feet (1963), he moved into television, directing episodes of The Human Jungle (1963–64), The Saint (1962–69) and The Avengers.[21] Producer Anthony Nelson Keys chose Baker as director because he felt his experience on such films as A Night to Remember gave him the technical expertise to handle the film's significant special effects requirements.[7] Baker, for his part, felt that his background on fact-based dramas such as A Night to Remember and The One That Got Away enabled him to give Quatermass and the Pit the air of realism it needed to be convincing to audiences.[15] He was impressed by Nigel Kneale's screenplay, feeling the script was "taut, exciting and an intriguing story with excellent narrative drive. It needed no work at all. All one had to do was cast it and shoot it."[22] He was also impressed with Hammer Films' lean set-up: having been used to working for major studios with thousands of full-time employees, he was surprised to find that Hammer's core operation consisted of just five people and enjoyed how this made the decision-making process fast and simple.[15] Quatermass and the Pit was the first film for which the director was credited as "Roy Ward Baker", having previously been credited as "Roy Baker". The change was made to avoid confusion with another Roy Baker who was a sound editor.[20] Baker later regretted making the change as many people assumed he was a new director.[15]

Filming took place between 27 February and 25 April 1967.[8] The budget was £275,000 (£5.47 million in 2023).[23] At this time, Hammer was operating out of the Associated British Studios in Elstree, Borehamwood. A lack of space meant that production was relocated to the nearby MGM Borehamwood studio.[6] There were no other productions working at the MGM Studios at this time so the Quatermass crew had full access to all the facilities of the studio.[24] Baker was particularly pleased to be able to use MGM's extensive backlot for the exteriors of the Underground station.[24] The production team included many Hammer regulars,[25] including production designer Bernard Robinson who, as an in-joke, incorporated a poster for Hammer's The Witches (1966) into the dressing of his set for the Hobbs End station.[26] Another Hammer regular was special effects supervisor Les Bowie. Baker recalled he had a row with Bowie, who believed the film was entirely a special effects picture when he tried to run the first pre-production conference.[16] Bowie's contribution to the film included the Martian massacre scene, which was achieved with a mixture of puppets and live locusts, and model sequences of London's destruction, including the climactic scene of the crane swinging into the Martian apparition.[27]

Music

[edit]Tristram Cary was chosen to provide the score for Quatermass and the Pit. He developed an interest in electronic music while serving in the Royal Navy as an electronics expert working on radar during the Second World War.[28] He became a professional composer in 1954, working in film, theatre, radio and television,[29] with credits including The Ladykillers (1955).[30] He said of his assignment: "I was not mad about doing the film because Hammer wanted masses of electronic material and a great deal of orchestral music. But I had three kids, all of which were at fee-paying schools, so I needed every penny I could get!"[31] Cary also recalled that "the main use of electronics in Quatermass, I think, was the violent shaking, vibrating sound that the "thing in the tunnel" gave off ... It was not a terribly challenging sound to do, though I never played it very loud because I didn't want to destroy my speakers—I did have hopes of destroying a few cinema loudspeaker systems, though it never happened."[32] Several orchestral and electronic cues from the film were released by GDI Records on a compilation titled The Quatermass Film Music Collection.[33] The soundtrack was released on yellow vinyl in the UK for Record Store Day 2017.[citation needed]

Title sequence

[edit]The title sequence of Quatermass and the Pit was devised to be evocative. Kim Newman, in his British Film Institute (BFI) monograph about the movie, states: "The words 'Hammer Film Production' appear on a black background. Successive jigsaw-piece cutaways reveal a slightly psychedelic skull. Swirling, infernal images are superimposed on bone – perhaps maps or landscapes – evoking both the red planet Mars and the fires of Hell. Beside this, the title appears in jagged red letters."[34]

Reception

[edit]Censors

[edit]The script was sent to John Trevelyan of the British Board of Film Censors in December 1966.[21] Trevelyan replied that the film would require an X certificate and complained about the sound of the vibrations from the alien ship, the showing of the Martian massacre, scenes of destruction and panic as the Martian influence takes hold, and the image of the Devil.[24]

Critical

[edit]Quatermass and the Pit premiered on 9 November 1967 and went on general release as a double feature with Circus of Fear on 19 November.[13] It was released in the US as Five Million Years to Earth in March 1968.[35] The critical reception was generally positive. Writing in The Times, John Russell Taylor found that, "after a slowish beginning, which shows up the deficiencies of acting and direction, things really start hopping when a mysterious missile-like object discovered in a London excavation proves to be a relic of a prehistoric Martian attempt (successful, it would seem) to colonize Earth [...] The development of this situation is scrupulously worked out and the film is genuinely gripping even when (a real test this) the Power of Evil is finally shown personified in hazy glowing outline, a spectacle as a rule more likely to provoke titters than gasps of horror."[36]

Paul Errol of the Evening Standard described the film as a "well-made, but wordy, blob of hokum", a view echoed by William Hall of The Evening News who described the film as "entertaining hokum" with an "imaginative ending".[37] A slightly more critical view was espoused by Penelope Mortimer in The Observer who said: "This nonsense makes quite a good film, well put together, competently photographed, on the whole sturdily performed. What it totally lacks is imagination."[38] Leslie Halliwell wrote: "The third film of a Quatermass serial is the most ambitious, and in many ways inventive and enjoyable, yet spoiled by the very fertility of the author's imagination: the concepts are simply too intellectual to be easily followed in what should be a visual thriller. The climax, in which the devil rears over London and is "earthed", is satisfactorily harrowing."[39]

Box office

[edit]According to Fox records, the film required $1.2 million in rentals to break even and made only $881,000 ($6.14 million in 2023).[40]

Legacy

[edit]The film was a success for Hammer and they quickly announced that Nigel Kneale was writing a new Quatermass story for them but the script never went further than a few preliminary discussions.[41] Kneale did eventually write a fourth Quatermass story, broadcast as a four-part serial, titled Quatermass, by ITV television in 1979, an edited version of which was also given a limited cinema release under the title The Quatermass Conclusion.[13] Quatermass and the Pit marked the return to directing for the cinema for Roy Ward Baker.[20]

Quatermass and the Pit continues to be generally well regarded among critics. John Baxter notes in Science Fiction in the Cinema that "Baker's unravelling of this crisp thriller is tough and interesting. [...] The film has moments of pure terror, perhaps the most effective that in which the drill operator, driven off the spaceship by the mysterious power within is caught up in a whirlwind that fills the excavation with a mass of flying papers."[42] John Brosnan, writing in The Primal Scream, found that "as a condensed version of the serial, the film is fine but the old black-and-white version, though understandably creaky in places and with inferior effects, still works surprisingly well, having more time to build up a disturbing atmosphere."[43] Bill Warren in Keep Watching the Skies! said: "The ambition of the storyline is contained in a well-constructed mystery that unfolds carefully and clearly."[44] Nigel Kneale had mixed feelings about the result "I was very happy with Andrew Keir, who they eventually chose, and very happy with the film. There are, however, a few things that bother me. ... The special effects in Hammer films were always diabolical."[27]

It has been suggested that Tobe Hooper's 1985 Lifeforce is largely a remake of Hammer's Quatermass and the Pit. In an interview, director Tobe Hooper discussed how Cannon Films gave him $25 million, free rein, and Colin Wilson's book The Space Vampires. Hooper then shares how giddy he was: "I thought I'd go back to my roots and make a 70 mm Hammer film."[45]

Home media release

[edit]Various DVDs of the film include a commentary from Nigel Kneale and Roy Ward Baker, as well as cast and crew interviews, trailers and an instalment of The World of Hammer TV series devoted to Hammer's forays into science fiction.[46]

A UK Blu-ray was released on 10 October 2011,[47] followed by releases in the US, Germany and Australia.[48]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hallenbeck & Meikle 2011, p. 135.

- ^ "Quatermass and the Pit". British Film Institute. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Quatermass and the Pit". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Hearn & Barnes 1999.

- ^ Murray 2006, p. 76.

- ^ a b Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e Kinsey 2007, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 116.

- ^ Mayer 2004, p. 155.

- ^ James Donald at IMDb

- ^ Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Murray 2006, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 117.

- ^ a b Mayer 2004, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Kneale & Baker, DVD Commentary

- ^ a b Baker 2000, p. 125.

- ^ Murray 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Barbara Shelley at IMDb

- ^ Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 129.

- ^ a b Kinsey 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Baker 2000, p. 124.

- ^ Kinsey 2007, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Kinsey 2007, p. 21.

- ^ Kinsey 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Kinsey 2007, p. 24.

- ^ a b Kinsey 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Huckvale 2008, p. 125.

- ^ Huckvale 2008, p. 126.

- ^ Newman 2019, p. 108.

- ^ Martell, p. 15.

- ^ Huckvale 2008, p. 129.

- ^ "The Quatermass Film Music Collection". SoundtrackCollector.com. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Newman 2019, p. 37.

- ^ Kinsey 2007, p. 67.

- ^ Taylor, John Russell (2 November 1967). "A Menace from Mars". The Times. London.

- ^ Mayer 2004, p. 152.

- ^ Mayer 2004, p. 153.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1989). Halliwell's Film Guide (7th ed.). London: Paladin. p. 827. ISBN 0-586-08894-6.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (1988). The Fox That Got Away: The Last Days of the Zanuck Dynasty at Twentieth Century – Fox. Secaucus, NJ: Lyle Stuart. p. 327. ISBN 9780818404856.

- ^ Murray 2006, p. 96.

- ^ Baxter 1970, p. 98.

- ^ Brosnan 1995, p. 149.

- ^ Warren 1982, p. 339.

- ^ Miller 2016, p. 180.

- ^ Chandler, Phil. "Quatermass and the Pit". dvdcult.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- ^ "Quatermass and the Pit". Blu-ray.com.

- ^ "Quatermass and the Pit". Blu-ray.com.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baker, Roy Ward (2000). The Director's Cut: A Memoir of 60 Years in Film and Television. Reynolds and Hearn. ISBN 978-1-9031-1102-4.

- Baxter, John (1970). Science Fiction in the Cinema. A.S. Barnes & Co. ISBN 978-0-3020-0476-0.

- Brosnan, John (1995). The Primal Screen. A History of Science Fiction Film. Orbit. ISBN 978-0-3562-0222-8.

- Hallenbeck, Bruce; Meikle, Dennis (2011). British Cult Cinema: Hammer Fantasy & Sci-fi. Hemlock Books. ISBN 978-0-9557-7744-8.

- Hearn, Marcus (1999). "Hammer's Quatermass Trilogy". The Quatermass Film Music Collection (CD liner). Various Artists. GDI. GDICD008.

- Hearn, Marcus; Barnes, Alan (2007) [1997]. The Hammer Story: The Authorised History of Hammer Films (2nd ed.). Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-8457-6185-1.

- Huckvale, David (2008). Hammer Film Scores and the Musical Avant-Garde. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3456-5.

- Kinsey, Wayne (2007). Hammer Films: The Elstree Studios Years. Tomahawk Press. ISBN 978-0-9531-9262-5.

- Kneale, Nigel; Roy Ward Baker (1998). Quatermass and the Pit DVD Commentary (Quatermass and the Pit DVD Special Feature). Anchor Bay.

- Mansell, John (1999). "Tristram Cary – Quatermass and the Pit". The Quatermass Film Music Collection (CD liner). Various Artists. GDI. GDICD008.

- Mayer, Geoff (2004). Roy Ward Baker. British Film Makers. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6354-1.

- Miller, Thomas (2016). Mars in the Movies: A History. McFarland, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- Murray, Andy (2006). Into The Unknown: The Fantastic Life of Nigel Kneale. Headpress. ISBN 978-1-9004-8650-7.

- Newman, Kim (2019). Quatermass and the Pit. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-8445-7791-0.

- Warren, Bill (1982). Keep Watching the Skies! American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties. Vol. I: 1950–1957. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-0479-7.

External links

[edit]- Quatermass and the Pit at the TCM Movie Database

- Quatermass and the Pit at IMDb

- Quatermass and the Pit at AllMovie

- Quatermass and the Pit at BritMovie (archived)

- The Quatermass Trilogy – A Controlled Paranoia

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch