Geneva Bible

| Geneva Bible | |

|---|---|

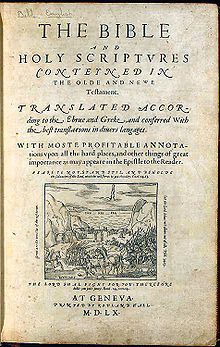

Geneva Bible 1560 edition | |

| Full name | Geneva Bible |

| Other names | Breeches Bible |

| NT published | 1557 |

| Complete Bible published | 1560 |

| Derived from | Tyndale Bible |

| Textual basis | Textus Receptus (New Testament) Masoretic Text and influence from Tyndale and Coverdale (Old Testament) |

| Publisher | Sir Rowland Hill of Soulton |

| Religious affiliation | Protestant (Reformed) |

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without forme and voyde, and darkeness was upon the depe, and the Spirit of God moved upon the waters. Then God said, "Let there be light" and there was light. For God so loved the world, that he hath given his only be gotten Son, that whosoever beleveth in him, should not perish, but have everlasting life. | |

The Geneva Bible is one of the most historically significant translations of the Bible into English, preceding the Douay Rheims Bible by 22 years, and the King James Version by 51 years.[1] It was the primary Bible of 16th-century English Protestantism and was used by William Shakespeare,[2] Oliver Cromwell, John Knox, John Donne and others. It was one of the Bibles taken to America on the Mayflower (Pilgrim Hall Museum has collected several Bibles of Mayflower passengers), and its frontispiece inspired Benjamin Franklin's design for the first Great Seal of the United States.[3]

The Geneva Bible was used by many English Dissenters, and it was still respected by Oliver Cromwell's soldiers at the time of the English Civil War, in the booklet The Souldiers Pocket Bible.[4]

Because the language of the Geneva Bible was more forceful and vigorous, most readers strongly preferred this version to the Great Bible. In the words of Cleland Boyd McAfee, "it drove the Great Bible off the field by sheer power of excellence".[5]

History

[edit]The Geneva Bible followed the Great Bible of 1539, the first authorized Bible in English, which was the authorized Bible of the Church of England.

During the reign of Mary I (1553–1558), who restored Catholicism and outlawed Protestantism in England, a number of English Protestant scholars fled to Geneva, which was then a republic in which John Calvin and, later, Theodore Beza, provided the primary spiritual and theological leadership. Among these scholars was William Whittingham who supervised the translation now known as the Geneva Bible, in collaboration with Myles Coverdale, Christopher Goodman, Anthony Gilby, Thomas Sampson, and William Cole. Whittingham was directly responsible for the New Testament, which was complete and published in 1557,[6] while Gilby oversaw the Old Testament. Several members of this group would later become prominent figures in the Vestments controversy.

The first full edition of this Bible, which included a revised New Testament, appeared in 1560,[6] and was published by Sir Rowland Hill of Soulton,[7][8][9][10][11] but it was not printed in England until 1575 (New Testament[6]) and 1576 (complete Bible[6]). Over 150 editions were issued; the last probably in 1644.[6] The first Bible printed in Scotland was a Geneva Bible, which was first issued in 1579.[6] In fact, the involvement of Knox (1514–1572) and Calvin (1509–1564) in the creation of the Geneva Bible made it especially appealing in Scotland, where in 1579 a law was passed requiring every household of sufficient means to buy a copy.[12]

Some editions from 1576 onwards[6] included Laurence Tomson's revisions of the New Testament. Some editions from 1599 onwards[6] used a new "Junius" version of the Book of Revelation, in which the notes were translated from a new Latin commentary by Franciscus Junius.

The annotations, a significant part of the Geneva Bible, were Calvinist and Puritan in character, and as such were disliked by the ruling pro-government Anglicans of the Church of England, as well as by James I, who commissioned the "Authorized Version", or King James Bible, in order to replace it. The Geneva Bible had also motivated the earlier production of the Bishops' Bible under Elizabeth I for the same reason, and the later Rheims–Douai edition by the Catholic community. The Geneva Bible nevertheless remained popular among Puritans and was in widespread use until after the English Civil War. The last edition was printed in 1644.[13]

The Geneva notes were surprisingly included in a few editions of the King James Version, as late as 1715.[6] Benjamin Franklin is understood to have been inspired by the frontispiece of the Geneva Bible in his design proposal for the first Great Seal of the United States.[14]

Translation and format

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Reformed Christianity |

|---|

|

| |

The Geneva Bible was the first English version to be translated entirely from the original languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. Though the text is principally just a revision of William Tyndale's earlier work of 1534, Tyndale had only fully translated the New Testament; he had translated the Old Testament through 2 Chronicles before he was imprisoned. The English refugees living in Geneva completed the first translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew to English. The work was led by William Whittingham.[15]

Textual basis

[edit]The Geneva Bible was translated from scholarly editions of the Greek New Testament and the Hebrew Scriptures that comprise the Old Testament. The English rendering was substantially based on the earlier translations by William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale (the Geneva Bible relies significantly upon Tyndale).[16]

Format

[edit]

Size

[edit]

The Geneva Bible was also issued in more convenient and affordable sizes than earlier versions. The 1560 Bible was in quarto format (218 × 139 mm type area), but pocket-size octavo editions were also issued, and a few large folio editions. The New Testament was issued at various times in sizes from quarto down to 32º (the smallest, 70×39 mm type area).[6]

Breeches Bible

[edit]Here are both the Geneva, Tyndale and the King James versions of Genesis 3:7 with original spelling (not modernized):[17]

Tyndale Bible

| Geneva Bible

| King James Bible

|

King James I and the Geneva Bible

[edit]

King James I's distaste for the Geneva Bible was not caused by the translation of the text into English, but rather the annotations in the margins. He felt strongly that many of the annotations were "very partial, untrue, seditious, and savoring too much of dangerous and traitorous conceits". In all likelihood, he saw the Geneva's interpretations of some biblical passages as anti-clerical "republicanism", which could imply church hierarchy was unnecessary. Other passages appeared particularly seditious, most notably references to monarchs as "tyrants".[18]

Examples of the commentary in conflict with the monarchy in the Geneva Bible (modern spelling) include:[19]

- Daniel 6:22 – "For he [Daniel] disobeyed the king’s wicked commandment in order to obey God, and so he did no injury to the king, who ought to command nothing by which God would be dishonoured."

- Daniel 11:36 – "So long the tyrants will prevail as God has appointed to punish his people: but he shows that it is but for a time."

- Exodus 1:19 – To the Hebrew midwives lying to their leaders, "Their disobedience herein was lawful, but their dissembling evil."

- 2 Chronicles 15:15-17 – King Asa "showed that he lacked zeal, for she should have died both by the covenant and by the law of God, but he gave place to foolish pity and would also seem after a sort to satisfy the law."

When toward the end of the conference two Puritans suggested that a new translation of the Bible be produced to better unify the Anglican Church in England and Scotland, James embraced the idea. He would not only be rid of those inconvenient annotations but have greater influence on the translation of the Bible as a whole. He commissioned and chartered a new translation of the Bible which would eventually become the most famous version of the Bible in the history of the English language. Officially known as the Authorized Version to be read in churches, the new Bible would come to bear his name as the so-called King James Bible or King James Version (KJV) elsewhere or casually. The first and early editions of the King James Bible from 1611 and the first few decades thereafter lack annotations, unlike nearly all editions of the Geneva Bible up until that time.[20]

Initially, the King James Version did not sell well and competed with the Geneva Bible. Shortly after the first edition of the KJV, King James banned the printing of new editions of the Geneva Bible to further entrench his version. However, Robert Barker continued to print Geneva Bibles even after the ban, placing the spurious date of 1599 on new copies of Genevas which were actually printed between about 1616 and 1625.[21]

Legacy

[edit]Although the King James Version was intended to replace the Geneva Bible, the King James translators relied heavily upon this version.[22] Bruce Metzger, in Theology Today 1960, observes the inevitable reliance the KJV had on the Geneva Bible. Some estimate that twenty percent of the former came directly from the latter. He further revels in the enormous impact the Geneva Bible had on Protestantism: "In short, it was chiefly owing to the dissemination of copies of the Geneva version of 1560 that a sturdy and articulate Protestantism was created in Britain, a Protestantism which made a permanent impact upon Anglo-American culture."[23]

The Puritan Separatists or Pilgrim Fathers aboard the Mayflower in 1620 brought to North America copies of the Geneva Bible.[24][25][26] German historian Leopold von Ranke observed that "Calvin was virtually the founder of America."[27]

See also

[edit]- Tyndale Bible (1526)

- Coverdale Bible (1535)

- Matthew Bible (1537)

- Taverner's Bible (1539)

- Great Bible (1539)

- Bishops' Bible (1568)

- Douay–Rheims Bible (1582)

- King James Bible (1611)

References

[edit]- ^ Metzger, Bruce (1 October 1960). "The Geneva Bible of 1560". Theology Today. 17 (3): 339–352. doi:10.1177/004057366001700308. S2CID 170946047.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (2006). Shakespeare: The Biography (First Anchor Books ed.). Anchor Books. p. 54. ISBN 978-1400075980.

- ^ "The Bible in American History: Creating a Great Seal for the New Nation". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce (1 October 1960). "The Geneva Bible of 1560". Theology Today. 17 (3): 351. doi:10.1177/004057366001700308. S2CID 170946047.

- ^ McAfee, Cleland Boyd, Study of the King James Bible, Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Herbert, AS (1968), Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible 1525–1961, London, New York: British and Foreign Bible Society, American Bible Society, SBN 564-00130-9.

- ^ Gregory, Olinthus (1833). Memoirs of the life, writings and character of the later John Mason Good. Fisher.

- ^ The Biblical Repository and Classical Review. 1835.

- ^ The Holy Bible ... With a General Introduction and Short Explanatory Notes, by B. Boothroyd. James Duncan. 1836.

- ^ Staging Scripture: Biblical Drama, 1350–1600. BRILL. 18 April 2016. ISBN 978-90-04-31395-8.

- ^ Beenham.), Thomas STACKHOUSE (Vicar of (1838). A New History of the Holy Bible, from the beginning of the world to the establishment of Christianity. L.P.

- ^ A Chronology of the English Bible, Bible researcher.

- ^ "The Reformed Reader introduction to the geneva bible for the historic Baptist faith". www.reformedreader.org. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ dseverance (15 October 2019). "The Geneva Bible: The First English Study Bible | Houston Christian University". hc.edu. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "The History of the Geneva Bible". Modernized Geneva Bible. 16 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Daniell, David (2003) The Bible in English: history and influence. New Haven and London: Yale University Press ISBN 0-300-09930-4, p. 300.

- ^ "Genesis 3:7 Parallel: And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons".

- ^ Ipgrave, Julia (2017). Adam in Seventeenth Century Political Writing in England and New England. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 14. ISBN 9781317185598. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

The Geneva Bible encouraged a political reading of the Scriptures. It famously incorporated in its notes and its translation elements that were considered seditious by James I and that were deliberately excluded from the new Authorised Version of 1611. In particular there were margin notes that appeared to suggest the legitimacy of resistance to overweening rulers, and there was the frequent use of the language of tyrant (a word expressly disallowed in James' Bible) and slave.

- ^ Barrett, Matthew (12 October 2011). "The Geneva Bible and Its Influence on the King James Bible". Founders Ministries. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "KJV: 400 Years (Issue 86) Fall 2011". Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Nicolson, Adam. God's Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible (HarperCollins, 2003)

- ^ "Geneva Bible | Description, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M. (October 1960). "The Geneva Bible of 1560". Theology Today. 17 (3): 339–352. doi:10.1177/004057366001700308. ISSN 0040-5736. S2CID 170946047.

- ^ The Geneva Bible: A Facsimile of the 1560 Edition. Hendrickson Bibles. Lloyd E. Berry. Hendrickson Publishers. 2007. ISBN 9781598562125. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

The Pilgrims brought the Geneva Bible with them on the Mayflower to Plymouth in 1620. In fact, the religious writings and sermons published by the members of the Plymouth colony suggest that the Geneva Bible was used exclusively by them.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "The Mayflower Quarterly". The Mayflower Quarterly. 73. General Society of Mayflower Descendants: 29. 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

This Geneva Bible, one of the Mayflower's precious books, belonged to William Bradford.

- ^ Greider, John C. (2008). The English Bible Translations and History: Millennium Edition (revised ed.). Xlibris Corporation (published 2013). ISBN 9781477180518. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower [...] brought with them copies of the Geneva Bible of 1560; printed in Geneva by Roland Hall.

- ^ "Calvin's Influence in America". ChristianityToday.com. 24 October 1975. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

External links

[edit]- Text

- Scanned copy of the original 1560 Geneva Bible

- Geneva Bible (1599)

- Geneva Bible Footnotes

- Geneva Bible online (1599)

- Modern Spelling Geneva Bible with Footnotes for the Gospels

- Works by or about Geneva Bible at the Internet Archive

- Articles

- The Geneva Bible of 1560 Archived 28 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine: article by Bruce Metzger originally printed in Theology Today

- Online version of Sir Frederic G. Kenyon's article in Hastings' Dictionary of the Bible, 1909

- Editions currently in print

- 1560 First Edition: Facsimile Reproduction

- 1560 First Edition Reduced size Facsimile Reproduction by Hendrickson

- 1599 Edition: Modern Spelling and Typesetting from The 1599 Geneva Bible Restoration Project (no illustrations)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch