Gibson Kyle

Gibson Kyle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1820 Ponteland, Northumberland |

| Died | (aged 82) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Newcastle railway station, 1850 (clerk of works) Angus & Co. warehouse, 1868 Chaucer Buildings, Grainger St West, 1869 |

Richard Gibson Kyle (1820–1903), known professionally as Gibson Kyle, was an English architect practising in and around Newcastle upon Tyne. His father was a Northumberland journeyman mason and contractor-builder. Kyle was articled to his uncle John Dobson and worked with him on local projects such as Newcastle railway station, some of the Quayside buildings, and the King Street-Queen Street block which was the site of a major fire in 1867.

Among his independent works, he designed an extension which forms part of the College of St Hild and St Bede, now part of Newcastle University, besides the Chaucer Building in Grainger Street West, tenements, baths for Newcastle Lunatic Asylum, and baths and a wash house for the general public. Around north-east England he designed a number of nonconformist chapels and parsonages, and he was architect to the Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral.

As a young man he lay in wait and caught a burglar who was carrying away 33 lb (15 kg) of lead. He was teetotal and took part in the temperance movement. He was involved in a number of business ventures in Newcastle, and he took active part in local politics.

Background

[edit]

Kyle's paternal grandparents were mason Joseph Kyle (1759 or 1760–1849),[1] and Jane Barnes. Kyle's father was also named Gibson Kyle (1789–1867),[2] and he was a mason.[3] Kyle's mother was Elizabeth Dobson (1793–1868).[4] In 1821 along with his brother-in-law John Dobson, Gibson Kyle senior was a witness in the indictment of the bailiffs and burgesses of Morpeth, regarding the "ruinous state of the bridge of that town." Kyle senior, the bridge surveyor for the county, reported that the bridge, known as Three Mile Bridge, was so narrow that he had to dismount from his horse at the widest part of the bridge, to let a carriage pass him.[5][nb 1] It was Gibson Kyle senior who in 1835 designed the replacement Lowford Bridge, a skew bridge that permitted the B6343 road to be straightened a little. His stone arches "threatened to collapse" but were rebuilt with the assistance of Edward Chapman of Newcastle, who replaced the stone with brick.[6] Gibson Kyle senior was one of the contractors for building Morpeth Gaol (designed by John Dobson in 1822–1828), and his servant Sarah Detchen who stole from him was the first convict to be jailed there.[7] By 1843 Kyle senior was a journeyman mason, a builder-contractor and an insolvent debtor.[8][9]

Life

[edit]Richard Gibson Kyle was born in Ponteland, Northumberland, in 1820, and died at 2 Roseville, Bensham, Gateshead on 21 January 1903, aged 82 years.[10][11] His wife was Mrs Elizabeth Dowson, (Hexham ca.1819 – Gateshead 1868), the former "active, intelligent and kind" matron of Newcastle Infirmary,[12][13][14] and widowed by 1851.[15] They married in Haltwhistle in July 1855,[16][17][18] and their son was the architect Alfred Gibson Kyle (1856–1940).[19][20][21][22] Gibson Kyle was a teetotaller,[23] and belonged to the Newcastle auxiliary of the United Kingdom Alliance.[24] He is buried in Elswick Cemetery, Newcastle.[10]

In 1842, Kyle caught a burglar. Thomas Middlemass, who worked in Richard Grainger's Clayton Street shop, had noticed that lead was going missing, and young Kyle was hidden away there to watch for the thief. He saw John Marshall enter by the window and leave with 33 lb (15 kg) of lead, and Marshall was still carrying it when Kyle caught him. The thief was taken to Court and committed to the sessions.[25]

In 1866, Kyle was called for jury service. The jury was reassured that although they would be dealing with a great number of cases, the majority would be "very trifling in description." The sessions began with a list of thefts.[26] In 1892, Kyle was called as a witness at the inquest regarding fatalities in the Gateshead Theatre Royal fire of 1892.[nb 2][27] Eleven people were killed in a crush at the gallery door, during a panic following cries of fire. Expert witnesses, including Kyle, stated that the number of exits and lack of fire precautions made the theatre unsafe.[28]

Business and local politics

[edit]Gibson Kyle was heavily involved in local business issues, including the gas lighting industry in 1859.[29] He or his father took part in the procession of directors of the North Eastern Railway Company at the opening of Jarrow docks in 1859.[30] In 1866 Kyle was a director of the Union Permanent Benefit Building Society, whose offices were at 93 Clayton Street, Newcastle.[31] Kyle was regularly involved in the sale of land with development plans. For example, in 1868 he was selling 13 villa sites on 13 acres of land at the "east end of East Bolden."[32] He also sold buildings and he was a director of the Tyne, Wear and Tees Property Trust.[33] For example, in 1864 he was advertising a pub, shops, houses and domestic lettings in Newcastle.[34] He was a moneylender, too. For example, in November 1888 he was offering £200,000 (equivalent to £28,140,747 in 2023) to lend at 3.75 percent,[35] and in March 1889 he had £45,000 (equivalent to £6,282,543 in 2023) to lend at 3.5–4 per cent.[36]

In 1868, Kyle was elected a town councillor for the West Ward of Gateshead, on a Ratepayers' Association ticket since he vowed to lower the rates, though he received both cheers and hisses when he won.[23] In 1874 Kyle was elected as a member of Newcastle Town Council for Westgate Ward, the polling having taken place in a shed in the cattle market, where the voting numbers had been low.[37]

Career

[edit]Kyle was apprenticed to his uncle John Dobson.[10] "Mr Dobson did not trouble himself much about articled pupils or apprentices. He was always too full of business to give either room or time for the purely elementary education of beginners. Mr Dobson insisted on some proficiency and fitness in those he employed. He was always approachable to his assistants ... He often said, If you err, err on the side of strength. He had a horror of shams, and warned young men of the dangers attending flimsy and cheap construction."[38] Kyle worked alongside Dobson and Richard Grainger, and was Grainger's foreman when some of their major works were carried out. Between them, they changed the face of Newcastle by demolishing and rebuilding. When they built the Central Station, Kyle was clerk of works. With Dobson he built "a magnificent pile of buildings on the Quayside," as well as other buildings in the city,[10] including a training college and other public buildings.[39]

Kyle's first office as an independent architect was at 16 Market Street, then in May 1865 he moved to 2 St Nicholas' Buildings, Newcastle.[40] By March 1892 he was working from 130 Pilgrim Street, Newcastle.[41] Kyle was appointed architect to the Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral, and he designed a "large number of churches" in the area. He was a "stickler for thoroughness," he was one of the founders of the Northern Architectural Association, and when young he was a "keen politician." His Newcastle Daily Chronicle obituary said,[10]

"There are none to whom the saying that their works live after them is more appropriate than the great architect, for though his most durable monuments pass away, they remain to exercise influence for many years, speaking to those who gaze upon them."[10]

In 1869 at Kyle's office in St Nicholas Buildings, Newcastle upon Tyne,[nb 3][42] Tom Bell aged 23, one of Kyle's assistants, fell through a skylight and was severely injured. He had been looking out of an upstairs window when he climbed out onto a skylight to retrieve a pen. The skylight gave way, and he dropped 40 feet into the lobby. He was "greatly stunned" and badly cut with broken glass. He was treated at the Infirmary, then taken home by his sisters.[43]

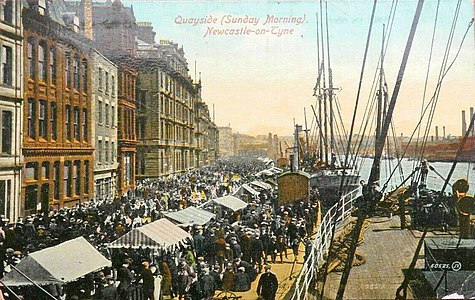

- Buildings by Dobson and Kyle on Quayside, Newscastle

- Newcastle Central Station in 1850

- St Nicholas Buildings

Connections with other architects

[edit]In Newcastle, Kyle associated with other architects, including his contemporary Septimus Oswald (1823–1894), whose funeral he attended in 1894.[44] Oswald designed Newcastle General Hospital (formerly the workhouse hospital) in 1870.[45] He was father of architect Joseph Oswald (1851–1930) who designed the Central Arcade, and Newcastle Breweries' head office in Newgate Street.[46]

One of Kyle's last assistants was James Newton Fatkin (c.1882–1940), who also came from Ponteland. After Kyle's death, Fatkin acquired and developed the business, designing flats at 63 Fern Avenue, Eslington terrace and Osborne Avenue, Newcastle. He designed "numerous cinemas throughout the North," and during World War II converted basements into air raid shelters.[47]

Joseph G. Angus of Low Fell (b.Gateshead 1842),[48] a member of the leather and rubber manufacturing family of Grainger Street West, was articled as an architect to Gibson Kyle. But "he was too fond of agricultural pursuits to settle down to plan drawing," so he emigrated to Natal around 1875, and farmed there.[49]

Works in association with John Dobson

[edit]King Street – Queen Street block, Akenside Hill, circa 1863

[edit]

This is the triangular block bounded to the north by Akenside Hill, to the south by Queens Street and to the east by the upper stepped end of King Street. On 20 December 1867 this new Italian-style block, worth £9,000 (equivalent to £1,087,724 in 2023) to £10,000 (equivalent to £1,208,582 in 2023), designed by Gibson and Kyle as part of Newcastle's Quayside improvement scheme, burnt down in a great fire.[50]

The fire was first discovered in the premises of Messrs Bell and Dunn, shiphandlers and hardwaremen, where a considerable quantity of very combustible material was stowed away, consisting of hemp, tar, rosin, and other articles usually sold by ship chandlers. Soon the premises were in a complete blaze, and the fire extended, spreading right and left, to the offices of Mr Southern, timber merchant, 9 Queen Street; Mr J. Liddel, the Mickley Coal Company; Mr Hilson Philipson, coal fitter; Mr Henry Scholefield, in Queen Street; Messrs Hall Brothers, in King Street; Messrs J.H. and P. Brown, merchants; and Messrs Forster, Blackett and Wilson, lead merchants, Queen Street, and others.[50]

This event occurred on the same spot as a previous explosion and fire of 1854. No-one was hurt on this occasion, and several heroic acts were reported, including that of plumber Caleb Jobling (1823–1869),[51][52] who was "very active in the dangerous task of breaking off the connections of the roofs by which the fire was prevented from spreading to the adjoining buildings."[53]

Independent works

[edit]Durham Diocesan Training School (extension), 1856–1858

[edit]

On 28 May 1856 Kyle was calling for tenders from prospective builders of this extension, which involved "erection of the principal's residence, and forming additional dormitories &c., in present building."[54] Because it was completed in the same period, Kyle is likely to have designed the Model School which was attached to the main building for teaching experience purposes. In 1858 the Durham Diocesan Female Training School (later called the College of St Hild) was opened close by. The architect of St Hild is unknown.[55]

This unlisted building extended by Kyle was known as the Durham Diocesan Training School for Masters between 1839 and 1886 when it was renamed Bede College. It trained elementary school masters, and by 1860 the numbers of pupils had increased from five to fifty.[56] The College of St Hild and St Bede is now part of Durham University.[55]

Former Methodist New Connexion Chapel and schoolroom, Ripon, 1859

[edit]Kyle called for tenders on 24 May 1859, for "a new chapel and school room for the Methodist New Connexion, in the city of Ripon.[57] in 1877 this building in Cemetery Road was demolished and replaced by the larger Melbourne Terrace Chapel, designed by Edward Taylor of York.[58]

Methodist New Connexion Chapel, Hartlepool, 1859–1860

[edit]On 29 October 1859 the foundation stone for this chapel was laid by Mrs Joseph Love, wife of benefactor Joseph Love of Willington Hall, Greater Willington. There was a "large and respectable" procession from the Freemasons' Hall, Hartlepool, and a "large gathering" at the site. There had been special trains booked for the guests, and seating platforms and banners had been set up. There was hymn-singing, a speech and a tea. Kyle's design, seating 800 people,[59] was "an elegant structure,"[60] and "somewhat Byzantine in character." It measured 70 by 42 feet, and included classrooms, schoolrooms and vestries.[59] In the gallery behind the pulpit was an organ by Nicholson of Newcastle.[nb 4][60]

The chapel was opened for services on Easter Sunday, 8 April 1860. There was a "spacious lecture hall" under the chapel, and a fund-raising bazaar was held there between 9 and 11 April. There were special sermons by guest speaker Rev. S. Hulme of Leeds on the following Sunday, and the public tea was held on Monday 16 April in the chapel's lecture hall.[61]

Methodist New Connexion Chapel, Spennymoor, 1860–1861

[edit]The foundation stone for the Methodist New Connexion Chapel at Spennymoor, Durham, was laid on 10 April 1860 "before a large assemblage" by benefactor Joseph Love of Durham. This was another of Kyle's designs. Rev. John Stokes preached, and the tea was provided by Tudhoe Ironworks.[62]

Former Primitive Methodist Chapel, Durham, 1860–1861

[edit]This building, later called the Jubilee Primitive Methodist Chapel, replaced a previous 1825 chapel in Silver Street, Durham, at a cost of £1,900 (equivalent to £223,948 in 2023) to £2,000 (equivalent to £235,735 in 2023).[63][64] The building committee, naming Kyle as architect, called for tenders for this work to be received by 21 July 1860.[65] This second chapel was in North Road, on a plot extending between the New North Road and Crossgate.[66] The laying of the foundation stone by Solicitor General Sir William Atherton MP, on 22 October 1860,[67][68] was a major event involving a procession from the town hall and a crowd of 2,000 people. The building was opened in October 1861, although the celebrating began on 19 May. The building "held 600, had galleries on 3 sides and boasted a starlight with 51 gas jets suspended from the ceiling."[nb 5][63] In 1959–1961 the Jubilee Chapel congregation was merged with Bethel Church and renamed North Road Methodist Church. Kyle's 1861 building was demolished in 1961.[69]

New Connexion Methodist Chapel, Jarrow, 1861

[edit]The foundation stone of this New Connextion Methodist Chapel near Ormonde Street at Jarrow was laid on 3 June 1861 by Matthew Stainton of South Shields. Kyle designed it to accommodate 300 people on the ground floor. Either side of the entrance hall were a classroom and vestry. The design was of "Italian character." It had:[70]

"... pressed bricks to the walling, and molded brick cornices, string-courses &c. The entrance doorway [was] well recessed, and, with the various windows, [had] arched heads. The interior [was] fitted up with open benches of stained and varnished deal, arranged so as to rise by easy steps from the level of the preacher's platform. The organ and choristers [were] placed on a gallery over the entrance and vestry.[70]

Former Free Methodist chapel and schools, Newcastle, 1861

[edit]Kyle called for tenders for this building in 1861.[71] It is possibly a red brick rebuild of the 1799 Lower Street Chapel,[72] sold by the Wesleyans to the United Methodist Free Church in 1863. It closed in 1939, and was demolished.[73]

Connexion Chapel at Witton Gilbert, 1861

[edit]

It is likely that this is the present Wesleyan Chapel at Witton Gilbert, also known as Witton Gilbert Methodist Chapel, which in the 19th century was used by the United Methodists. It is on the north side of the B6312 road, where it branches northward from Front Street.[74]

The Witton Gilbert chapel was opened with an "overflowing congregation" on Sunday 15 December 1861. The stone building was designed in the "early pointed period of ecclesiastical architecture." The porch has a "pointed doorway with trefoil arch opening, splayed jambs, moulded labels, &c. The gable fronting the street is pierced with pointed arch window openings, having splayed dressings. The interior fittings [were] of Petersburg pine, wrought, stained and varnished. A platform [was] provided in the recess of the rear gable, to answer for public meetings as well as for the usual Sunday services. Adjoining the chapel [was] a vestry, with an entrance from the porch." Kyle was credited with the design, and James Smith was the builder.[75]

Former Wesley Chapel, Prudhoe Street, Newcastle, 1861–1862

[edit]The Wesley Chapel was a replacement for the smaller Wesley Chapel in Bridge Street. This new one was designed by Kyle for the United Free Methodists at a cost of £3,500. It was built near the police station at the east end of Prudhoe Street.[76][77] The foundation stone was laid on 3 December 1861 by John Reay of Wallsend, who was presented with a silver trowel. A "large number" of people came to the ceremony. In his speech, Reay said that he had been a Methodist for over fifty years, he had laid foundation stones for more than ten chapels, and he was a trustee for sixteen schools and chapels. A time capsule in the form of a bottle was placed under the cornerstone, containing a "local newspaper, names of the elected trustees, architect and contractors, a copy of the circuit plan, and of a placard announcing the event, and a small coin of the realm." A "large company" of perhaps 2,000 people attended the "public soirée," or tea, which followed at the New Town Hall.[78][79]

The chapel was opened for services to "numerous congregations" on 17 September 1862. It was designed for a congregation of 800 in the "Italian Gothic style of architecture." It had two porches giving access to the galleries. On the ground floor were lecture rooms, classrooms to seat 200 children, and vestries.[77] It was "built with moulded bricks and white-stone dressings to openings, cornices, tablings &c ... The whole of the interior woodwork was of Petersburg pine, stained and varnished. Fresh air [was] admitted through the cast-iron columns that support[ed] the galleries, and through ventilators in the walls. The chapel and schoolrooms [were] warmed by hot water apparatus ... Four starlights and ventilating tubes [were] placed in the ceiling of the chapel."[78] Wilson and Berry contracted for the joinery and carpentry, and J. Kyle contracted the mason work.[77] The Building News reported:[80]

It is one of the finest specimens of the combination of art with utility which the modern architectural revival has given to Newcastle ... The prevalent red-brick front has been most judiciously relieved by the stone dressings; and the windows, to the mullions of which a very dark tint has been given, are most effectively placed with regard to utility, both for illuminating purposes and architectural effect. In the interior also, the decorations harmonise well with the various fittings; the panels of the gallery which run round the building have received a share of decoration which is too often denied to the same portion of other churches; and the pulpit, which like the gallery, is of light, polished pinewood, has its carved panels elegantly inlaid with crimson. The columns which support the gallery are of iron, and furnish another example of the successful application of that metal in architecture.[80][81]

In the 1970s, Prudhoe Street was demolished, and the Eldon Square Shopping Centre was built in its place.[82]

Choppington Parsonage, Morpeth, 1867

[edit]

Kyle called for tenders for the erection of Choppington parsonage, near Morpeth, Northumberland, in April and May 1867.[83][84] The church itself was designed by Joseph Clarke of London, architect to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.[85] It was intended for the local mining community. When newly built, the church stood "on an eminence to the south-east side of the northern turnpike, on the Willow Bridge Farm ... [and was] pleasantly situated, situated as it [was], surrounded by a plantation, through which access [had] been made to the [church] building. The "new parsonage house for the incumbent" was built after the 1866 church and on its east side, and the Ecclesiastical Commission voted £1,400 (equivalent to £156,581 in 2023) from the Queen Anne's Bounty, for construction.[86]

Former Angus & Co. warehouse, Grainger Street, Newcastle, 1867–1868

[edit]

In April 1867, Kyle was calling for tenders for "different works to be done in erecting shops, offices, four-storey warehouse &c. in St John's Lane (later re-named Grainger Street West), Newcastle.[nb 6][87] This warehouse, founded on 3 September 1867,[88] and opened on 26 August 1868, and built for India-rubber dealer George Angus, was next to the old Savings Bank. The Angus warehouse is now demolished; the site is now 27 Grainger Street West.[89] It was part of a development called the St John's Lane Improvements, between Grainger Street and Westgate Street. This direct route between Newcastle railway station and the city centre had previously been "narrow and inconvenient," with its "beggarly and ricketty" houses which contained a "broad block of buildings that were a hotbed and receptacle of fevers and other epidemic diseases," and a "population of the lowest class." The development, to be known as Grainger Street West, would join Grainger Street to the railway station via a "broad carriage road and footpaths."[90][91]

The rebuild was, however, delayed, causing "great complaints" because no-one initially wanted to move premises there. Finally leather factor and merchant George Angus & Co., acquired a 3,000 sq yd (2,500 m2) L-shaped site and built this three-storey warehouse next to the pre-existing Savings Bank. The foundation stone was laid on 3 September 1867. The time capsule inside the cornerstone contained local daily papers, coins of the realm, and the following document:[92]

This stone was laid on Tuesday, the 3rd day of September, in the year 1867. It forms the foundation of the first block of buildings erected on the site of old St John's Lane, at the expense of Geo. Angus Esq., proprietor. It was designed by Mr. Gibson Kyle, contracted for by Mr. Robert Robson and Messrs. J. and W. Lowry, and superintended by Mr T. Alderson, clerk of the works. The foundation stone was laid by John Henry Angus, eldest son of the proprietor., Sept. 3, 1867. Newcastle on Tyne.[92]

Following the ceremony there was a dinner with speeches and toasts.[92] During the excavations for the foundations, some groundworkers contracted by Mr Robson dug too deeply at 12–14 ft (3.7–4.3 m), and too close to the premises of Mr Bremner, a pork butcher in Scotch Arms Yard. At nearly midnight on 17 July 1868 the premises of Mr Bremner, and the end of the house of Mr Ritson next door, had "fallen into Mr Angus' building." Bremner sued for £28 5s 6d.[93]

The new build was "extensive and beautiful." In the manner of 19th century city warehouses, the decorative front of the building was for sales, and the back was for manufacture and deliveries. The three factory and storage areas at the rear measured 90 ft (27 m) by 45 ft (14 m), and there was also a cellar,[90] a glass-roofed counting house and a tan works.[88] The front ground floor was a shop, selling India rubber and gutta-percha. The front upper floors contained office rental space at the front,[90] a "display of dressed and fancy French leathers" on the first floor and (temporarily) a belt and hose piping factory on the second floor.[88] Next to the building, on the Bigg Market side, a 600 sq yd (500 m2) plot containing a large tannery works was purchased for Angus' new hose belt factory. There were 70–80 employees working on the main site.[90][91]

The Newcastle Journal reported that the 90 ft (27 m) commercial French Gothic frontage was "noble and pleasing ... tastefully ornamented with carved stone."[90] The Newcastle Daily Chronicle said it was Italian Gothic.[88] The windows gave the upstairs offices "an abundance of light." The Newcastle Journal said:[90]

The front is tastefully ornamented with designs in carved stone. The ornaments of the lower row of capitals consist of oak leaves and acorns, and wild hemlock, and are emblematic principally of the leather trade, in which those productions are used. There are also carvings of polyanthuses, columbine, fern, rose, passion flower, vine, &c. The building has three dormer windows, finished with carved finials. Over the entrance is a bull's head, the crest of the firm. The corbels and capitals in front are remarkably well finished. The material is all of stone, of a remarkably hard and durable character, and has been brought from Wide Open and Brunton Quarries. The architect is Mr Gibson Kyle, of this town. The carving is by Mr Curry, and is a work of art."[90]

[91] At the opening there was a "sumptuous" dinner in the warehouse cellar for a "large number of visitors,"[90] including 70 workmen. The bells of St John's and St Andrew's rang merry peals, and the proceedings were jubilant.[88] Gibson Kyle was listed among the guests, but the architectural sculptor Curry was not. The Newscastle Journal reported:[90]

The pillars supporting the upper floor were wreathed with ivy and other evergreens; and numbers of flags were suspended from the roof and sides of the warehouse. One of the flags bore the coat of arms of the firm - a bull's head on a blue ground, with the words Fortis est veritas.[nb 7] A great curiosity was a half of the hide of a hippopotamus, which was hung against the southern wall. It weighed 240 lb (110 kg), and was 2.5 in (6.4 cm) thick in the centre. The hide of the hippopotamus, it appears, is an article of commerce, and is used for machinery purposes. This extraordinary article was surmounted by the appropriate adage, Nothing like leather.[90]

Parsonage, Rookhope, 1868

[edit]On 9 July 1858, Kyle called for tenders for the construction of a parsonage at Rookhope, Durham.[42] It is now a hotel, known as Rookhope Vicarage.[94][95]

Former School at United Methodist Free Church, Willington Quay, Newcastle, 1869

[edit]The foundation stone for this school, designed by Kyle for 250 children at a cost of £400 (equivalent to £46,671 in 2023), was laid on 2 March 1869. The building was completed on 5 September in the same year, "the work of erection having been ... vigorously prosecuted." It was a 40 ft (12 m) stone and brick extension of the chapel's east end, in the "Early English style of architecture." The builders were Batey and Stevens of Willington, Newcastle. In celebration, there were special services in the chapel on 5 September, and on 6 September there was an afternoon tea and a public meeting attended by ministers and gentlemen. One purpose of this meeting may have been to arrange further finance, since the church still owed £200 (equivalent to £27,014 in 2023) for the building works.[96] The school received an average attendance of 239 pupils.[97]

The chapel and school survived until at least 1890 when they were shown on an Ordnance Survey map. They have since been demolished.[98][99]

Chaucer Buildings, 53–61 Grainger Street, Newcastle, 1869

[edit]

Chaucer Buildings at 53–61 Grainger Street, Newcastle, is a Grade II listed building. It was built as a Freemasons' hall, together with shops and offices. The style is Venetian Gothic. It has carved capitals, carved ornaments above the windows, and a crocketed gable with a curved finial.[100][101]

Former South Shields Tabernacle, Laygate Lane, South Shields, 1869–1870

[edit]

Kyle called for tenders from builders, to erect a Baptist chapel in South Shields, with a deadline of 9 July 1869.[102] On Wednesday 28 October 1870, the foundation stone was laid by Mrs Archibald Stevenson for the South Shields Tabernacle, in Laygate Lane, South Shields. The building was erected with stone dressings in the "Italian style of architecture." At 65 ft (20 m) by 50 ft (15 m) it accommodated 750 to 800 people. It had galleries, a platform, and a pulpit at the east end. It was designed by Kyle at a cost of £2,000 (equivalent to £241,716 in 2023). There was a plan for schools to be added at a later date. The building is now demolished.[103]

Wallsend United Methodist Free Church, 1871

[edit]In December 1870, Kyle was calling for tenders for "enlarging, partially rebuilding and re-seating" work on Wallsend United Methodist Church.[104]

Public restaurant, South Shields (alterations), 1886

[edit]This premises was altered by Kyle, and taken over in 5 Market Place, South Shields, by the Public Restaurant Company, a restaurant chain previously known as the Penny Diner System. The customer base was working men and the poor, and the principle was that "by a little arrangement and contrivance, food could be provided of a good and substantial character at very much cheaper rates than was generally done." Although the object was, "the good they could do, rather than the profit they could make," the company was nevertheless turning a small profit. Soup and bread at this restaurant cost a penny. The company aimed soon to provide "dinners of two courses at the price of sixpence."[105]

Central Hall, Blyth (extensions and alterations), 1892

[edit]Kyle called for tenders from builders, for the extension and alteration of the Central Hall, Blyth, in March 1892. At that point he was working from 130 Pilgrim Street, Newcastle.[41]

Tenements, Pilgrim Street, Newcastle, 1893

[edit]Kyle's plans to build lodging houses and single-room tenements in Pilgrim Street were chosen on 2 March 1893, following a prize competition held by Newcastle's Town Improvement Committee.[106] A description of the plans for the tenements appeared in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle two days later.[107]

The elevation of the building, although necessarily of a plain character, is relieved by pleasant architectural features. The grouping of the windows, and the arrangement of the general mass of the building, present a successful effort to secure a picturesque effect in an essentially utilitarian structure. There are to be 50 tenements, each possessing from 226 square feet to 236 square feet, this area being exclusive of bed recess. The main entrance, nine feet wide, is about the centre of the block from which a six foot wide fire-proof concrete staircase is approached. The superintendent's office will be so placed as to overlook the entrance. The access to all the tenements and out offices is from cement concrete galleries and landings at rear of the buildings, an arrangement which is intended to give privacy to the main frontage, which is three stories high. Each tenant will have a separate entrance lobby as a protection from the weather. Efficient ventilators, improved sash windows and hinged fanlights over the doors are to be constructed. The gas lighting will be under the care of the superintendent, and during the day-time each tenement will be amply lighted by means of a double window. A coal bunker, bed recess and sink are provided to every tenement. The attic floor is entirely open for clothes drying in wet weather, and is amply lighted and ventilated. The lavatories, dust-bins and wash-houses are placed 20ft to the rear of the main building, and an access for carts into the yard is provided for in Mr Kyle's plan.[107]

Tenements were becoming known for overcrowding of the poor by 1900 due to developing social conditions,[108] but in 1893 this one was designed for single occupancy.[107] Pilgrim Street had been an important medieval street, but the south side was replaced when the Swan House roundabout and internal motorway were built in 1967. It is not known whether this tenement building still exists.[109]

Tenements and lodging houses, Millers Hill, Newcastle, 1893

[edit]in 1893 Kyle designed a block of 50 tenements for married couples, and a lodging house for women, in Miller's Hill, Newcastle, winning first prize in a competition for plans at Newcastle Town Hall. Having inspected the exhibition of plans, the Newcastle Daily Chronicle reported:[110]

The Miller's Hill will almost certainly be improved by the erections to be built from the prime designs that were yesterday on view. It would be almost impossible to imagine neater buildings than those contemplated. The front elevation of the 50 tenements shows an exceedingly charming block, with a wide entrance, pretty windows, and an altogether tasteful front. The appearance of the lodging house for women is also very neat, and gains in attractiveness from the bay window provided for above the entrance ... The first place was awarded to the fine designs of Mr Gibson Kyle, 130 Pilgrim Street, Newcastle ... The cost of the Miller's Hill lodging house is to be £7,000 (equivalent to £980,666 in 2023).[110]

Former Newcastle Lunatic Asylum baths and wash houses, 1894

[edit]Newcastle Corporation employed Kyle and met in the Town Hall on 3 April 1894, to arrange a loan of £10,000 (equivalent to £1,438,277 in 2023) for a baths and wash houses extension to the city mental hospital.[111]

Former Gallowgate Corporation Baths, Newcastle, 1896

[edit]

The Corporation Baths in Gallowgate was Kyle's last work, opened on 10 August 1896.[112] He won the commission for this in open competition.[113][39][114] This building replaced previous baths and wash-houses at the corner of Newgate Street, demolished to facilitate the widening of Gallowgate.

The building was "very neat and tasteful," in the "English style of architecture." It had a 76 ft (23 m) frontage and a baths entrance in Gallowgate, and a 213 ft (65 m) frontage in Strawberry Lane. It was constructed of "Ruabon red pressed bricks and stone from the Dunhouse Quarry, near Barnard Castle ... The men's first class bath hall [was] provided with eight fire clay baths and two shower baths. The second class hall [had] eight baths and two shower baths," with room for more. There were similar first and second-class facilities for women, plus "other apartments." There was a wash-house entrance in Strawberry Lane, the wash-house having "36 compartments, fitted with all the most modern steam and other appliances, required in such places. It was opened by Alderman R.H. Holmes, JP, who was given a "gold key" by Kyle. Holmes said that "such a place was not opened as a business investment; it was opened solely to promote cleanliness, to meet the necessity of the working class population; and he referred to the benefits that such an institution, especially the wash-house department, was calculated to confer on those who used it."[112][115] This building was demolished in 1972, and the site is now a car park.[116]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The 12th or 13th century Old Morpeth Bridge was partially demolished in 1835 and the remains are listed. In 1836 Lowford Bridge was constructed downstream. Sources: Historic England. "Morpeth Old Bridge (1020744)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 August 2020. and Historic England. "Lowford Bridge (1303122)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ In 1866 the building had been a United Methodist Free Church. After the congregation moved away, it became a music hall. It was then let for stage plays and for use by the Salvation Army. By 1892 Mr Turner had leased it as a theatre. It is not known whether Kyle designed or adapted the original chapel.

- ^ St Nicholas' Buildings is now a Grade II listed building 1024772, designed in 1850 by William B. Parnell, not Kyle.

- ^ The organ maker was James Nicholson (1819–ca.1890) of Postern, Newcastle on Tyne.

- ^ Durham County Record Office records say it held 300 people.

- ^ This probably refers to the Angus warehouse development, but may include the Chaucer Buildings also.

- ^ Fortis est veritas or "strength is truth" is the motto of Oxford's coat of arms.

References

[edit]- ^ "Release by the proprietors of the Northumberland Glassworks". tyneandweararchives.org.uk. Tyne and Wear Archives. 4 May 1824. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.; "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 4 September 2020. Deaths Dec 1849 Kyle Joseph Newcastle T 25 307

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 7 August 2020. Deaths Sep 1867 Kyle Gibson 78 Tynemouth 10b 126; "Deaths: Kyle". Shields Daily News. 7 August 1867. p. 3 col 6. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Whereas Gibson Kyle". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 3 December 1831. p. 3 col 4. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Deaths". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 25 July 1868. p. 8 col 7. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Civil side: before Mr Justice Bayley and a special jury". Tyne Mercury; Northumberland and Durham and Cumberland Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 13 March 1821. p. 4 col 5. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Morton, J. (12 July 2016). "The Great North Road". northeastlore.com. North East Lore. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Northumberland quarter sessions". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 26 July 1828. p. 2 col 1. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Insolvent debtors: Saturday the 16th day of December 1843". Bell's New Weekly Messenger. British Newspaper Archive. 24 December 1843. p. 7 col 6. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Insolvent debtor". Durham County Advertiser. 20 October 1843. p. 1 col 4. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Mr Gibson Kyle". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 24 January 1903. p. 4 col 2. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Northumberland Archives: Forster papers". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "H6, the medical charities of Newcastle". The Northern tribune; a periodical for the people. Vol. 1. British Newspaper Archive. 1854. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Whellan, William (1855). History, topography, and directory of Northumberland, comprising a general survey of the county, and a history of the town and county of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, with separate historical, statistical, and descriptive sketches of the boroughs of Gateshead and Berwick-upon-Tweed, and all the towns ... wards, and manors. To which is subjoined a list of the seats of the nobility and gentry. London: Whittaker & Co. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 26 July 2020. Deaths Mar 1868 Kyle Elizabeth 49 Gateshead 10a 414

- ^ 1851 England Census HO107/2406 p.1

- ^ "Marriages: at Haltwhistle". Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 7 July 1855. p. 8 col.6. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Marriage: at Haltwhistle". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 6 July 1855. p. 8 col.5. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 26 July 2020. Marriages Jun 1855 Doson Elizabeth and Kyle Gibson Haltwhistle 10b 381

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 26 July 2020. Births Jun 1856 Kyle Alfred Gibson Durham 10a 247

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 26 July 2020. Deaths Mar 1940 Kyle Alfred G. 83 Gateshead 10a 1844

- ^ "The late Mr Gibson Kyle, funeral at Elswick Cemetery". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 24 January 1903. p. 3 col 6. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Geo. H. Storey Sons & Parker". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 8 April 1940. p. 3 co. 5. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Gateshead, West Ward". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 3 November 1868. p. 3 col 3. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Newcastle auxiliary of the United Kingdom Alliance". Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 18 December 1869. p. 5 col.4. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Newcastle police: Thursday". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 25 March 1842. p. 7 col 4. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Durham midsummer quarter sessions". Durham County Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 5 July 1861. p. 2 col.1. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Lloyd, Matthew (2020). "The Theatre Royal, High Street, Gateshead". arthurlloyd.co.uk. Arthur Lloyd. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "The theatre panic at Gateshead, resumption of the inquest". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 15 January 1892. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Improved coal gas". Durham Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 4 March 1859. p. 1 col.4. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Fordyce, T. (1867). "From: Local Records or Historical Register of Remarkable Events". dmm.org.uk. Durham Mining Museum. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "New building society". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 14 June 1866. p. 1 col.2. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Building sites at East Boldon, near Sunderland, for sale". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 19 May 1868. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "The Tyne, Wear and Tees Property trust". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive. 13 July 1876. p. 1 col.1. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "For sale by private contract". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 17 February 1864. p. 1 col.6. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Two hundred thousand". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 7 November 1888. p. 2 col.6. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Money". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 18 March 1889. p. 2 col.5. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Westgate election". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 30 November 1874. p. 3 col 8. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "John Dobson". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 1 January 1887. p. 16 col.1. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Death of Mr Gibson Kyle, the well-known architect". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 23 January 1903. p. 5 col 3. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Mr Gibson Kyle". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 4 May 1865. p. 1 col.2. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Central Hall, Blyth". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 9 March 1892. p. 2 col.5. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Parsonage at Rookhope". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 23 July 1868. p. 2 col 2. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Accident to an architect's assistant". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 16 July 1869. p. 5 col 3. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Funeral of Mr S. Oswald". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 1 December 1894. p. 8 col4. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Newcastle General Hospital". newcastlephotos. Hospital Records Database. January 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Michael (2009). "Architectural taste and patronage in Newcastle upon Tyne, 1870- 1914" (PDF). nrl.northumbria.ac.uk. Northumbria University: Northumbria Research Link. pp. 74, 289. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Newcastle architect". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 31 August 1940. p. 5 col1. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 1 September 2020. Births Sep 1842 Angus Joseph George Gateshead XXIV 120

- ^ "The Hon. F.T. Angus". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 12 April 1916. p. 4 col.3. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The fire in Newcastle". Shields Daily News. 21 December 1867. p. 3 col 4. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 7 August 2020. Deaths Dec 1869 Jobling Caleb 46 Newcastle T. 10b 42

- ^ "Deaths: Jobling". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 26 October 1869. p. 2 col 1. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Great fire in Akenside Hill Newcastle, terrible destruction of property, four houses burnt". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 21 December 1867. p. 3 col 2. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Durham Diocesan Training School". Durham County Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 6 June 1856. p. 5 col 1. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ a b Ashby, Gemma (2013–2016). "College of St Hild and St Bede: our history". dur.ac.uk. Durham University. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Wilkinson, Kenneth Riley (1968). The Durham diocesan training school for masters, 1839 – 1886. etheses.dur.ac.uk (Thesis). Durham University. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "To builders and contractors". Richmond & Ripon Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 28 May 1859. p. 1 col.1. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Protestant nonconformity". british-history.ac.uk. British History Online. 1961. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b "New chapel at Hartlepool". Durham Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 2 September 1859. p. 8 col.3. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Opening of a New Connexion Methodist chapel at Hartlepool". Durham Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 13 April 1860. p. 7 col.1. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Opening of the New Connexion Chapel, Church-Field, Hartlepool". Hartlepool Free Press and General Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 7 April 1860. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Methodist New Connexion chapel at Spennymoor". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 11 April 1860. p. 2 col.4. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ a b Hill, Christopher (19 March 2018). "My Primitive Methodists: Durham Primitive Methodist chapel". myprimitivemethodists.org.uk/. The Methodist Church. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ "Primitive Methodist Chapel (Durham City)". keystothepast.info/. Durham County Council Archaeology Section (Keys to the Past). 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "To builders". Durham Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 13 July 1860. p. 4 col 5. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "New chapel at Durham". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 12 April 1860. p. 2 col.4. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "On Monday". Carlisle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 26 October 1860. p. 7 col.3. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "The Solicitor General at Durham". Sheffield Daily Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 25 October 1860. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Durham County Record Office, Ref. M/DDV 635

- ^ a b "Jarrow". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 4 June 1861. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Free Methodist Chapel and schoold, Newcastle". Durham Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 25 October 1861. p. 5 col 2. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Newcastle-under-Lyme". dmbi.online/. A dictionary of Methodism. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "United Methodist Free Church". british-history.ac.uk/. British History Online: Victoria County History. 1963. pp. 56–64. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Institute, Womens (1960). "A little history: the story of our village". wittongilbert.com. County Durham Village Websites. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "New Connexion Chapel at Witton Gilbert". Durham Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 20 December 1861. p. 5 col 5. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Prudhoe Street was behind Marks & Spencer on Northumberland Street

- ^ a b c "Opening of the Wesley Chapel, Prudhoe Street". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 18 September 1862. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Laying the foundation stone of a Methodist chapel". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 6 December 1861. p. 5 col.5. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Free Church Methodists' new chapel, foundation stone ceremony". Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 7 December 1861. p. 6 col.4. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The Prudhoe Street Chapel". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 2 October 1862. p. 2 col.4. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Opening of the Prudhoe Street Wesleyan Chapel". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 19 September 1862. p. 5 col.6. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Prudhoe Street, Newcastle". co-curate.ncl.ac.uk. Co-curate. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "To builders". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 30 April 1867. p. 2 col 3. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "To builders". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 3 May 1867. p. 22 col3. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Paul the Apostle (1041422)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Consecration of St Paul's Church, Choppington". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 17 November 1866. p. 2 col4. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ "To builders". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 18 April 1867. p. 2 col 3. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Opening of Messrs Geo. Angus & Co's new warehouses, Newcastle". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 27 August 1868. p. 4 col 2. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Opening of Messrs Angus & Co.'s new premises, Grainger St West". Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 29 August 1868. p. 5 col 5. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Grainger Street West, opening of Messrs Angus's new premises". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 27 August 1868. p. 2 col 5. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Improvements in Newcastle: Messrs G. Angus and new premises". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 28 August 1868. p. 5 col 1. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Messrs. George Angus and Co.'s new premises". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 4 September 1867. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Bremner vs Angus". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 24 July 1868. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Vicarage Rookhope". facebook.com. Facebook. 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Image of Rookhope Vicarage

- ^ "Opening of a new school at Willington Quay". Shields Daily Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 6 September 1869. p. 2 col 3. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Kelly's Directory of Durham (1890). "Willington Quay, Historical Account, 1890". co-curate.ncl.ac.uk. Co-Curate. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Morrison, Jennifer. "Tyne and Wear HER(11304): Willington Quay, Western Road, United Methodist Free Church - Details". twsitelines.info. Tyne and Wear Archaeology. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Morrison, Jennifer. "Tyne and Wear HER(11305): Willington Quay, United Methodist Free Church, school - Details". twsitelines.info. Tyne and Wear Archaeology. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Chaucer Buildings (1024864)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Newgate Centre and 67 Clayton Street: 3.1.7 - 53-61 Grainger Street, Chaucer Buildings (Grade II)" (PDF). simpsonandbrown.co.uk. Simpson & Brown architects. October 2009. p. 28. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "To builders". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 29 June 1869. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "South Shields Tabernacle, Laygate Lane, South Shields". Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 1 October 1870. p. 8 col.2. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "To builders". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 31 December 1870. p. 2 col.1. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Opening of a public restaurant in South Shields". Shields Daily Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 22 April 1886. p. 3 col.7. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Proposed lodging houses and tenements". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 2 March 1893. p. 8 col.1. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "Single room tenements". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 4 March 1893. p. 5 col.6. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Gazeley, Ian; Newell, Andrew (June 2009). "No Room to Live: Urban Overcrowding in Edwardian Britain" (PDF). core.ac.uk. University of Sussex. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Pilgrim Street". co-curate.ncl.ac.uk. Co-curate. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The municipal departure in Newcastle, exhibition of plans at the Town Hall". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 9 March 1893. p. 8 col.5. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Newcastle Corporation and its borrowing, the extensikon of the City Lunatic Asylum". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 7 April 1894. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Opening of new baths and wash-houses". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archives. 11 August 1896. p. 4 col 5. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Opening of new baths and wash houses at Newcastle". Dundee Courier. British Newspaper Archive. 12 August 1896. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Public baths Newcastle north-east England". freepages.rootsweb.com. Ancestry.com. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Title missing". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 15 August 1896. p. 2 col 5. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Jones, Tim. "Hanging out: Gallowgate". timarchive.freeuk.com. Time Archive. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

External links

[edit]- "Photograph of Rev. J Raine (1791-1858), Mr Gibson Kyle, architect (1820-1903), Rev. W..." discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/. The National Archives. 1854. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- "Tyne and Wear HER(5149): Ouseburn, Lime Street, No. 30, Flour Mill - Details". twsitelines.info. Sitelines. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch