Written language

A written language is the representation of a language by means of writing. This involves the use of visual symbols, known as graphemes, to represent linguistic units such as phonemes, syllables, morphemes, or words. However, written language is not merely spoken or signed language written down, though it can approximate that. Instead, it is a separate system with its own norms, structures, and stylistic conventions, and it often evolves differently than its corresponding spoken or signed language.

Written languages serve as crucial tools for communication, enabling the recording, preservation, and transmission of information, ideas, and culture across time and space. The orthography of a written language comprises the norms by which it is expected to function, including rules regarding spelling and typography. A society's use of written language generally has a profound impact on its social organization, cultural identity, and technological profile.

Relationship with spoken and signed language

[edit]

Writing, speech, and signing are three distinct modalities of language; each has unique characteristics and conventions.[2] When discussing properties common to the modes of language, the individual speaking, signing, or writing will be referred to as the sender, and the individual listening, viewing, or reading as the receiver; senders and receivers together will be collectively termed agents. The spoken, signed, and written modes of language mutually influence one another, with the boundaries between conventions for each being fluid—particularly in informal written contexts like taking quick notes or posting on social media.[3]

Spoken and signed language is typically more immediate, reflecting the local context of the conversation and the emotions of the agents, often via paralinguistic cues like body language. Utterances are typically less premeditated, and are more likely to feature informal vocabulary and shorter sentences.[4] They are also primarily used in dialogue, and as such include elements that facilitate turn-taking; these including prosodic features such as trailing off and fillers that indicate the sender has not yet finished their turn. Errors encountered in spoken and signed language include disfluencies and hesitation.[5]

By contrast, written language is typically more structured and formal. While speech and signing are transient, writing is permanent. It allows for planning, revision, and editing, which can lead to more complex sentences and a more extensive vocabulary. Written language also has to convey meaning without the aid of tone of voice, facial expressions, or body language, which often results in more explicit and detailed descriptions.[6]

While a speaker can typically be identified by the quality of their voice, the author of a written text is often not obvious to a reader only analyzing the text itself. Writers may nevertheless indicate their identity via the graphical characteristics of their handwriting.[7]

Written languages generally change more slowly than their spoken or signed counterparts. As a result, the written form of a language may retain archaic features or spellings that no longer reflect contemporary speech.[8] Over time, this divergence may contribute to a dynamic of diglossia.

Grammar

[edit]There are too many grammatical differences to address, but here is a sample. In terms of clause types, written language is predominantly declarative (e.g. It's red.) and typically contains fewer imperatives (e.g. Make it red.), interrogatives (e.g. Is it red?), and exclamatives (e.g. How red it is!) than spoken or signed language. Noun phrases are generally predominantly third person, but they are even more so in written language. Verb phrases in spoken English are more likely to be in simple aspect than in perfect or progressive aspect, and almost all of the past perfect verbs appear in written fiction.[9]

Information packaging

[edit]Information packaging is the way that information is packaged within a sentence, that is the linear order in which information is presented. For example, On the hill, there was a tree has a different informational structure than There was a tree on the hill. While, in English, at least, the second structure is more common, the first example is relatively much more common in written language than in spoken language. Another example is that a construction like it was difficult to follow him is relatively more common in written language than in spoken language, compared to the alternative packaging to follow him was difficult.[10] A final example, again from English, is that the passive voice is relatively more common in writing than in speaking.[11]

Vocabulary

[edit]Written language typically has higher lexical density than spoken or signed language, meaning there is a wider range of vocabulary used and individual words are less likely to be repeated. It also includes fewer first and second-person pronouns and fewer interjections. Written English has fewer verbs and more nouns than spoken English, but even accounting for that, verbs like think, say, know, and guess appear relatively less commonly with a content clause complement (e.g. I think that it's OK.) in written English than in spoken English.[12]

History

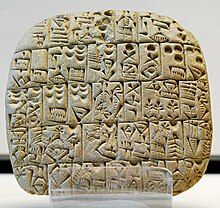

[edit]Writing developed independently in a handful of different locations, namely Mesopotamia and Egypt (c. 3200 – c. 3100 BCE), China (c. 1250 BCE), and Mesoamerica (c. 1 CE).[13] Scholars mark the difference between prehistory and history with the invention of the first written language.[14] The first writing can be dated back to the Neolithic era, with clay tablets being used to keep track of livestock and commodities. The first example of written language can be dated to Uruk, at the end of the 4th millennium BCE.[15] An ancient Mesopotamian poem tells a tale about the invention of writing:

Because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat, the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

Origins

[edit]

The origins of written language are tied to the development of human civilization. The earliest forms of writing were born out of the necessity to record commerce, historical events, and cultural traditions.[17] The first known true writing systems were developed during the early Bronze Age (late 4th millennium BCE) in ancient Sumer, present-day southern Iraq. This system, known as cuneiform, was pictographic at first, but later evolved into an alphabet, a series of wedge-shaped signs used to represent language phonemically.[18]

At roughly the same time, the system of Egyptian hieroglyphs was developing in the Nile valley, also evolving from pictographic proto-writing to include phonemic elements.[19] The Indus Valley civilization developed a form of writing known as the Indus script c. 2600 BCE, although its precise nature remains undeciphered.[20] The Chinese script, one of the oldest continuously used writing systems in the world, originated around the late 2nd millennium BCE, evolving from oracle bone script used for divination purposes.[21]

Influence on society

[edit]The development and use of written language has had profound impacts on human societies, influencing everything from social organization and cultural identity to technology and the dissemination of knowledge.[15] Plato (c. 427 – 348 BCE), through the voice of Socrates, expressed concerns in the dialogue "Phaedrus" that a reliance on writing would weaken one's ability to memorize and understand, as written words would "create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories". He further argued that written words, being unable to answer questions or clarify themselves, are inferior to the living, interactive discourse of oral communication.[22]

Written language facilitates the preservation and transmission of culture, history, and knowledge across time and space, allowing societies to develop complex systems of law, administration, and education.[16][page needed] For example, the invention of writing in ancient Mesopotamia enabled the creation of detailed legal codes, like the Code of Hammurabi.[14][page needed] The advent of digital technology has revolutionized written communication, leading to the emergence of new written genres and conventions, such as interactions via social media. This has implications for social relationships, education, and professional communication.[23][page needed]

Literacy and social mobility

[edit]Literacy is the ability to read and write. From a graphemic perspective, this ability requires the capability of correctly recognizing or reproducing graphemes, the smallest units of written language. Literacy is a key driver of social mobility. Firstly, it underpins success in formal education, where the ability to comprehend textbooks, write essays, and interact with written instructional materials is fundamental. High literacy skills can lead to better academic performance, opening doors to higher education and specialized training opportunities.[24][better source needed]

In the job market, proficiency in written language is often a determinant of employment opportunities. Many professions require a high level of literacy, from drafting reports and proposals to interpreting technical manuals. The ability to effectively use written language can lead to higher paying jobs and upward career progression.[25][better source needed]

Literacy enables additional ways for individuals to participate in civic life, including understanding news articles and political debates to navigating legal documents.[26][better source needed] However, disparities in literacy rates and proficiency with written language can contribute to social inequalities. Socio-economic status, race, gender, and geographic location can all influence an individual's access to quality literacy instruction. Addressing these disparities through inclusive and equitable education policies is crucial for promoting social mobility and reducing inequality.[27]

Marshall McLuhan's perspective

[edit]The Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980) primarily presented his ideas about written language in The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962). Therein, McLuhan argued that the invention and spread of the printing press, and the shift from oral tradition to written culture that it spurred, fundamentally changed the nature of human society. This change, he suggested, led to the rise of individualism, nationalism, and other aspects of modernity.[28]

McLuhan proposed that written language, especially as reproduced in large quantities by the printing press, contributed to a linear and sequential mode of thinking, as opposed to the more holistic and contextual thinking fostered by oral cultures. He associated this linear mode of thought with a shift towards more detached and objective forms of reasoning, which he saw as characteristic of the modern age. Furthermore, he theorized about the effects of different media on human consciousness and society. He famously asserted that "the medium is the message", meaning that the form of a medium embeds itself in any message it would transmit or convey, creating a symbiotic relationship by which the medium influences how the message is perceived.

While McLuhan's ideas are influential, they have also been critiqued and debated. Some scholars argue that he overemphasized the role of the medium (in this case, written language) at the expense of the content of communication.[29] It has also been suggested that his theories are overly deterministic, not sufficiently accounting for the ways in which people can use and interpret media in varied ways.[30]

Diglossia and digraphia

[edit]Diglossia is a sociolinguistic phenomenon where two distinct varieties of a language – often one spoken and one written – are used by a single language community in different social contexts.[31]

The "high variety", often the written language, is used in formal contexts, such as literature, formal education, or official communications. This variety tends to be more standardized and conservative, and may incorporate older or more formal vocabulary and grammar.[32] The "low variety", often the spoken language, is used in everyday conversation and informal contexts. It is typically more dynamic and innovative, and may incorporate regional dialects, slang, and other informal language features.[33]

Diglossic situations are common in many parts of the world, including the Arab world, where the high Modern Standard Arabic variety coexists with other, low varieties of Arabic local to specific regions.[34] Diglossia can have significant implications for language education, literacy, and sociolinguistic dynamics within a language community.[35]

Analogously, digraphia occurs when a language may be written in different scripts. For example, Serbian may be written using either the Cyrillic or Latin script, while Hindustani may be written in Devanagari or the Urdu alphabet.[36]

Orthography

[edit]Writing systems can be broadly classified into several types based on the units of language they correspond with: namely logographic, syllabic, and alphabetic.[37] They are distinct from phonetic transcriptions with technical applications, which are not used as writing as such. For example, notation systems for signed languages like SignWriting been developed,[38] but it is not universally agreed that these constitute a written form of the sign language in themselves.[39]

Orthography comprises the rules and conventions for writing a given language,[40] including how its graphemes are understood to correspond with speech. In some orthographies, there is a one-to-one correspondence between phonemes and graphemes, as in Serbian and Finnish.[41] These are known as shallow orthographies. In contrast, orthographies like that of English and French are considered deep orthographies due to the complex relationships between sounds and symbols.[42] For instance, in English, the phoneme /f/ can be represented by the graphemes ⟨f⟩ as in ⟨fish⟩, ⟨ph⟩ as in ⟨phone⟩, or ⟨gh⟩ as in ⟨enough⟩.[43]

Orthographies also include rules about punctuation, capitalization, word breaks, and emphasis. They may also include specific conventions for representing foreign words and names, and for handling spelling changes to reflect changes in pronunciation or meaning over time.[44]

See also

[edit]- Foreign-language writing aid

- Graphocentrism

- History of ancient numeral systems

- List of languages by first written account

- List of language disorders

- List of writing systems

- Literary language

- Standard language

- Text linguistics

References

[edit]- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 17; Primus (2003), p. 6.

- ^ Chafe (1994).

- ^ Baron, Naomi S. (2008). Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531305-5.

- ^ Biber (1988).

- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 22.

- ^ Tannen (1982).

- ^ Subaćius (2023), p. 306.

- ^ Lerer (2007).

- ^ Biber et al. (1999), p. 461.

- ^ Smolka (2017).

- ^ Biber et al. (1999), p. 938.

- ^ Biber et al. (1999), p. 668.

- ^ Houston (2004).

- ^ a b Roth (1997).

- ^ a b Ong (1982).

- ^ a b Goody (1986).

- ^ Robinson (2007).

- ^ Crawford, Harriet (2004). Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53338-6.

- ^ Schmandt-Besserat (1997).

- ^ Parpola (1994).

- ^ Boltz (1994).

- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 6.

- ^ Crystal (2006).

- ^ Snow, C. (2002). Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program in Reading Comprehension. Rand Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-3105-1.

- ^ Brandt, Deborah (2001). Literacy in American Lives. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00306-3.

- ^ Levine, P. (2013). We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For: The Promise of Civic Renewal in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993942-8.

- ^ Gorski, P. C.; Sapp, J. L. (2018). Case Studies on Diversity and Social Justice Education. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-71072-5.

- ^ Leech, G. N. (1963). "The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man". The Modern Language Review (Book review). 58 (4): 542. ISSN 0026-7937. JSTOR 3719923.

- ^ Lister, Martin (2009). New Media: A Critical Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-43161-3.

- ^ Carey, James W. (2008). "Overcoming Resistance to Cultural Studies". In Carey, James W.; Adam, G. Stuart (eds.). Communication as Culture (Rev. ed.). pp. 96–112. doi:10.4324/9780203928912-12. ISBN 978-0-203-92891-2.

- ^ Ferguson (1959), pp. 325–340.

- ^ Hudson, Richard A. (1996). Sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29668-7.

- ^ Romaine, S. (1995). Bilingualism. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19539-9.

- ^ Badawi, Elsald; Carter, Mike G.; Gully, Adam (2003). Modern Written Arabic: A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-66749-4.

- ^ Myers-Scotton, Carol (2006). Multiple Voices: An Introduction to Bilingualism. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21936-1.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), pp. 231–232.

- ^ Daniels & Bright (1996).

- ^ Galea (2014).

- ^ Meletis (2020), p. 69.

- ^ Crystal (2008).

- ^ Venezky (1999).

- ^ Roberts (2013), p. 96.

- ^ Kessler & Treiman (2005), pp. 120–134.

- ^ Carney (1994).

Works cited

[edit]- Biber, Douglas (1988). Variation Across Speech and Writing. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42556-8.

- ———; Johansson, Stig; Leech, Geoffrey; Conrad, S.; Finegan, Edward (1999). Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-23725-4.

- Boltz, William G. (1994). The Origin and Early Development of the Chinese Writing System. American Oriental Society. ISBN 0-940490-78-1.

- Borgwaldt, Susanne R.; Joyce, Terry, eds. (2013). Typology of Writing Systems. Benjamins current topics. Vol. 51. John Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-0270-3.

- Roberts, David. "A tone orthography typology". In Borgwaldt & Joyce (2013), pp. 85–112.

- Carney, Edward (1994). A Survey of English Spelling. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-00668-3.

- Condorelli, Marco; Rutkowska, Hanna, eds. (2023). The Cambridge Handbook of Historical Orthography. Cambridge handbooks in language and linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-48731-3.

- Subaćius, Giedrius. "Materiality of writing". In Condorelli & Rutkowska (2023), pp. 305–323.

- Crystal, David (2006). Language and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86859-4.

- Chafe, Wallace (1994). Discourse, Consciousness, and Time: The Flow and Displacement of Conscious Experience in Speaking and Writing. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10054-8.

- Crystal, David (2008). Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5296-9.

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Ferguson, Charles A. (1959). "Diglossia". Word. 15 (2): 325–340. doi:10.1080/00437956.1959.11659702. S2CID 239352211.

- Coulmas, Florian (2002). Writing Systems: An Introduction to Their Linguistic Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78217-3.

- Galea, Maria (2014). SignWriting (SW) of Maltese Sign Language (LSM) and its development into an orthography: Linguistic considerations (PhD thesis). University of Malta. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Goody, John (1986). The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33962-9.

- Houston, Stephen D. (2004). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83861-0.

- Kessler, Brett; Treiman, Rebecca (2005). "Writing Systems and Spelling Development". In Snowling, Margaret J.; Hulme, Charles (eds.). The Science of Reading: A Handbook. Blackwell. pp. 120–134. ISBN 978-1-4051-1488-2.

- Lerer, Seth (2007). Inventing English: A Portable History of the Language. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-17447-3.

- Meletis, Dimitrios (2020). The Nature of Writing: A Theory of Grapholinguistics. Grapholinguistics and Its Applications. Vol. 3. Brest: Fluxus. doi:10.36824/2020-meletis. ISBN 978-2-9570549-2-3. ISSN 2681-8566.

- ———; Dürscheid, Christa (2022). Writing Systems and Their Use: An Overview of Grapholinguistics. Trends in Linguistics. Vol. 369. De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-075777-4.

- Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Methuen. ISBN 978-0-416-71380-0.

- Parpola, Asko (1994). Deciphering the Indus Script. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43079-8.

- Primus, Beatrice (2003). "Zum Silbenbegriff in der Schrift-, Laut- und Gebärdensprache—Versuch einer mediumübergreifenden Fundierung" [On the concept of syllables in written, spoken and sign language—an attempt to provide a cross-medium foundation]. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft (in German). 22 (1): 3–55. doi:10.1515/zfsw.2003.22.1.3. ISSN 1613-3706.

- Robinson, Andrew (2007). The Story of Writing. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28660-9.

- Roth, Martha Tobi (1997). Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-0-7885-0378-8.

- Schmandt-Besserat, Denise (1997). How Writing Came About. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77704-0.

- Smolka, Vladislav (2017). "What Comes First, What Comes Next: Information Packaging in Written and Spoken Language". Auc Philologica (1): 51–61. doi:10.14712/24646830.2017.4. ISSN 2464-6830.

- Tannen, Deborah (1982). Spoken and Written Language: Exploring Orality and Literacy. Ablex. ISBN 978-0-89391-099-0.

- Venezky, Richard L. (1999). The American Way of Spelling: The Structure and Origins of American English Orthography. Guilford. ISBN 978-1-57230-469-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Coulmas, Florian (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21481-6.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch