National Lampoon (magazine)

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (October 2020) |

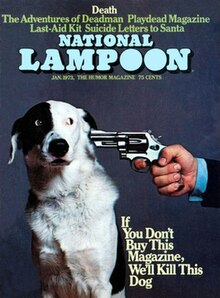

Cover of the January 1973 "Death" issue, featuring the dog Cheeseface | |

| Editor | Douglas Kenney (1970–1975) |

|---|---|

| Categories | Humor |

| Format | Magazine |

| Circulation | 1,000,096 |

| Publisher | Matty Simmons (1970–1989) |

| Founder | Douglas Kenney Henry Beard Robert Hoffman |

| Founded | 1969 |

| First issue | April 1970 |

| Final issue Number | November 1998 issue 246 |

| Company | Twenty First Century Communications (1970–1979) National Lampoon, Inc. (1979–1990) J2 Communications (1990–1998) |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City |

| Language | English |

| ISSN | 0027-9587 |

National Lampoon was an American humor magazine that ran from 1970 to 1998. The magazine started out as a spinoff from The Harvard Lampoon.

National Lampoon magazine reached its height of popularity and critical acclaim during the 1970s, when it had a far-reaching effect on American humor and comedy. The magazine spawned films, radio, live theater, various sound recordings, and print products including books. Many members of the publication's creative staff went on to contribute creatively to successful media of all types.

During the magazine's most successful years, parody of every kind was a mainstay; surrealist content was also central to its appeal. Almost all the issues included long text pieces, shorter written pieces, a section of actual news items (dubbed "True Facts"), cartoons and comic strips. Most issues also included "Foto Funnies" or fumetti, which often featured nudity. The result was an unusual mix of intelligent, cutting-edge wit, combined with some crass, bawdy jesting.[1] The magazine declined during the late 1980s and ceased publication in 1998.

Projects that use the "National Lampoon" (NL) brand name continued to be produced, but under its production company successor, National Lampoon, Inc.[2] The 50th anniversary of the magazine took place in 2020 and, to celebrate, the magazine was issued digitally for the first time by Solaris Entertainment Studio.[citation needed]

Overview

[edit]National Lampoon writers joyfully targeted every kind of phoniness, and had no specific political stance (even though individual staff members had strong political views). The magazine's humor often pushed far beyond the boundaries of what was generally considered appropriate and acceptable. It was especially anarchic, satirically attacking what was considered holy and sacred. As Teddy Wayne described it, "At its peak, the [National Lampoon] produced some of the bleakest and most controlled furious humor in American letters."[3]

Thomas Carney, writing in New Times, traced the history and style of the National Lampoon and the impact it had on comedy's new wave. "The National Lampoon", Carney wrote, "was the first full-blown appearance of non-Jewish humor in years—not anti-Semitic, just non-Jewish. Its roots were W.A.S.P. and Irish Catholic, with a weird strain of Canadian detachment.... This was not Jewish street-smart humor as a defense mechanism; this was slash-and-burn stuff that alternated in pitch but moved very much on the offensive. It was always disrespect everything, mostly yourself, a sort of reverse deism."[4]

P. J. O'Rourke, editor-in-chief of the magazine in 1978, went even further in his characterization of the magazine's humor:

What we do is oppressor comedy.... "Woody Allen says, 'I'm just a regular shmuck like you." Our kind of comedy says, "I'm O.K.; you’re an asshole." We are ruling class. We are the insiders who have chosen to stand in the doorway and criticize the organization. Our comic pose is superior. It says, "I’m better than you and I'm going to destroy you." It"s an offensive, very aggressive form of humor.[5]

The magazine was a springboard to the cinema of the United States for a generation of comedy writers, directors, and performers. Various alumni went on to create and write for Saturday Night Live, The David Letterman Show, SCTV, The Simpsons, Married... with Children, Night Court, and various films, including National Lampoon's Animal House, Caddyshack, National Lampoon's Vacation, and Ghostbusters. The characteristic humor of Spy magazine, The Onion, Judd Apatow, Jon Stewart, and Stephen Colbert is difficult to imagine without the influence of National Lampoon.[3]

As co-founder Henry Beard described the experience years later: "There was this big door that said, 'Thou shalt not.' We touched it, and it fell off its hinges."[6]

The magazine

[edit]Publication history

[edit]National Lampoon was started in 1969 by Harvard graduates and Harvard Lampoon alumni Douglas Kenney, Henry Beard, and Robert Hoffman,[7] when they first licensed the "Lampoon" name for a monthly national publication.[a] While still with The Harvard Lampoon, in the years 1966 to 1969, Kenney and Beard had published a number of one-shot parodies of Playboy, Life, and Time magazines;[8][9] they had also written the popular Tolkien parody book Bored of the Rings.[9]

The National Lampoon's first issue, dated April 1970, went on sale on March 19, 1970.[10] Kenney (editor) and Beard (executive editor) oversaw the magazine's content, while Hoffman (managing editor) handled legal and business negotiations.[8][9] After a shaky start, the magazine rapidly grew in popularity. Like The Harvard Lampoon, individual issues had themes, including such topics as "The Future", "Back to School", "Death", "Self-Indulgence", and "Blight". The sixth issue (September 1970), entitled "Show Biz", got the company in hot water with The Walt Disney Company after a lawsuit was threatened because of the issue's cover, which showed a drawing of Minnie Mouse topless, wearing pasties.[11]

The magazine's finest period was from 1971 to 1975, when Beard, Hoffman, and a number of the original creators departed.[12] The National Lampoon's most successful sales period was 1973–75:[b] Its national circulation peaked at 1,000,096[7] copies sold of the October 1974 "Pubescence" issue.[13] The 1974 monthly average was 830,000, which was also a peak.[c]

Although the glory days of National Lampoon ended in 1975, the magazine remained popular and profitable long after that point. As some of the original creators departed, the magazine saw the emergence of John Hughes and editor-in-chief P.J. O'Rourke, along with artists and writers such as Gerry Sussman, Ellis Weiner, Tony Hendra, Ted Mann, Peter Kleinman, Chris Cluess, Stu Kreisman, John Weidman, Jeff Greenfield, Bruce McCall, and Rick Meyerowitz.

National Lampoon continued to be produced on a monthly schedule throughout the 1970s and the early 1980s, and did well during that time.

A more serious decline set in around the mid-1980s: as described in a New York Times profile of the magazine from August 1984, "circulation of the magazine [had] fallen from a high of 638,000 to about 450,000. Publishing revenues were down to $9 million in 1983 from $12.5 million in 1981."[15]

In 1985, company CEO Matty Simmons took over as the magazine's editor-in-chief.[15] He fired the entire editorial staff, and appointed his two sons, Michael and Andy Simmons, as editors[7] and Larry "Ratso" Sloman as executive editor. Peter Kleinman returned to the magazine as creative director and editor. That year, each monthly issue was devoted to a single topic, with the first being "A Misguided Tour of New York."[15] In November 1986, National Lampoon moved to a bimonthly schedule, publishing six issues a year instead of every month.

J2 Communications bought the magazine and its properties in 1990. In 1991, an attempt at monthly publication was made; nine issues were produced that year,[16] and cartoonist Drew Friedman come on board as comics editor, introducing the works of Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware to a wider audience.[17]

After this, J2 decided instead to focus on licensing the "National Lampoon" brand, exhibiting very little interest in the actual magazine, only publishing it sporadically and erratically. To retain the rights to the Lampoon name, J2 was contractually obligated to publish only one new issue of the magazine per year, so for the rest of the 1990s the number of issues per year declined precipitously. Only two issues were released in 1992.[18] This was followed by one issue in 1993,[19] five in 1994, and three in 1995. For the last three years of its existence, the magazine was published only once a year. The final issue was published in 1998.

In 2007, in association with Graphic Imaging Technology, Inc., National Lampoon, Inc. released a collection of the entire 246 issues of the magazine in PDF format. The cover of the DVD box featured a remake of the January 1973 "Death" issue, with the caption altered to read "If You Don't Buy This DVD-ROM, We'll Kill This Dog". The pages are viewable on both Windows (starting with Windows 2000) and Macintosh (starting with OSX) systems.

Cover art

[edit]The magazine's original art directors were cartoonist Peter Bramley and Bill Skurski, founders of New York's Cloud Studio, an alternative-culture outfit known at the time for its eclectic style. Bramley created the Lampoon's first cover and induced successful cartoonists Arnold Roth and Gahan Wilson to become regular contributors.

Beginning with the eighth issue, the art direction of the magazine was taken over by Michael C. Gross, who directed the look of the magazine until 1974. Gross achieved a unified, sophisticated, and integrated look for the magazine, which greatly enhanced its humorous appeal.[11] A number of the National Lampoon's most acerbic and humorous covers were designed or overseen by Gross, including:

- Court-martialed Vietnam War mass-murderer William Calley sporting the guileless grin of Alfred E. Neuman, complete with the parody catchphrase 'What, My Lai?" (August 1971)[20]

- The iconic Argentinian revolutionary Che Guevara being splattered with a cream pie (January 1972)[21]

- A dog looking worriedly at the muzzle of a revolver pressed to its head, with what became a famous caption: "If You Don't Buy This Magazine, We'll Kill This Dog" (January 1973): The cover was conceived by writer Ed Bluestone.[22][d] Photographer Ronald G. Harris initially had a hard time making the dog's plight appear humorous instead of pathetic. The solution was to cock the revolver; the clicking sound caused the dog's eyes to shift into the position shown. This was the most famous Lampoon cover gag, and it was selected by ASME as the seventh-greatest magazine cover of the last 40 years.[22][23][24] This issue is among the most coveted and collectible of all the National Lampoon's issues.

- A replica of the starving child from the cover of George Harrison's charity album The Concert for Bangladesh, rendered in chocolate and with a large bite taken out of its head (July 1974)[25]

Michael Gross and Doug Kenney chose a young designer from Esquire named Peter Kleinman to succeed the team of Gross and David Kaestle. During his Lampoon tenure, Kleinman was also the art director of Heavy Metal magazine, published by the same company. The best known of Kleinman's Lampoon covers were "Stevie Wonder with 3-D Glasses" painted by Sol Korby,[26] a photographed "Nose to The Grindstone" cover depicting a man's face being pressed against a spinning grinder wheel for the Work issue, the "JFK's First 6000 Days" issue featuring a portrait of an old John F. Kennedy, the "Fat Elvis" cover which appeared a year before Elvis Presley died, and many of the Mara McAfee covers done in a classic Norman Rockwell style. Kleinman designed the logos for Animal House and Heavy Metal. Kleinman left in 1979 to open an ad agency.

He was succeeded by Skip Johnson, the designer responsible for the Sunday Newspaper Parody and the "Arab Getting Punched in the Face" cover of the Revenge issue. Johnson went on to The New York Times. He was followed by Michael Grossman, who changed the logo and style of the magazine.

In 1984, Kleinman returned as creative director and went back to the 1970s logo and style, bringing back many of the artists and writers from the magazine's heyday. He left four years later to pursue a career in corporate marketing. At that time, the National Lampoon magazine entered a period of precipitous decline.[citation needed]

Staff and contributors

[edit]The magazine was an outlet for some notable writing and drawing talents. Rick Meyerowitz, a longtime contributor, broke down the magazine's talent in this fashion:[27]

- The Founders: Doug Kenney, Henry Beard

- Present at the Birth: Michael O'Donoghue, George W. S. Trow, Christopher Cerf, John Weidman, Meyerowitz, Michel Choquette

- The Cohort: Arnold Roth, Tony Hendra, Sam Gross, Sean Kelly, Anne Beatts, Charles Rodrigues

- The First Wave: John Hughes, Brian McConnachie, Chris Miller, Gerald Sussman, Ed Subitzky, P.J. O'Rourke, Bruce McCall, Stan Mack

- The Second Coming: M. K. Brown, Ted Mann, Shary Flenniken, Danny Abelson & Ellis Weiner, Wayne McLoughlin

- The End of the Beginning: Ron Barrett, Jeff Greenfield, Ron Hauge, Fred Graver

Other important contributors included Chris Rush, Derek Pell, Chris Cluess, Al Jean, and Mike Reiss. The work of many important cartoonists, photographers, and illustrators appeared in the magazine's pages, including Neal Adams, John E. Barrett, Vaughn Bodē, Peter Bramley, Chris Callis, Frank Frazetta, Edward Gorey, Rich Grote, Robert Grossman, Buddy Hickerson, Jeff Jones, Raymond Kursar, Andy Lackow, Birney Lettick, Bobby London, Mara McAfee, David C. K. McClelland, Marvin Mattelson, Joe Orlando, Ralph Reese, Warren Sattler, Michael Sullivan, B. K. Taylor, Boris Vallejo, and Gahan Wilson.

Features

[edit]Editorials

[edit]Every regular monthly issue of the magazine had an editorial at the front of the magazine. This often appeared to be straightforward but was always a parody. It was written by whoever was the editor of that particular issue, since that role rotated among the staff; Douglas Kenney had been the main writer of them for the first few issues. Some issues were guest-edited.

True Facts

[edit]"True Facts" was a section near the front of the magazine that contained true but ridiculous items from real life. Together with the masthead, it was one of the few parts of the magazine that was factual. As was explained in the introduction to the "True Facts" 1981 newsstand special, the "True Facts" column was started in 1972 by Henry Beard, and it was based on a feature called "True Stories" in the British publication Private Eye. It was essentially a column of funny news briefs.

P. J. O'Rourke created the first "True Facts Section" in August 1977. This section included photographs of unintentionally funny signage, extracts from ludicrous newspaper reports, strange headlines, and so on.

In 1981 and for many subsequent years John Bendel was in charge of the "True Facts" section of the magazine. Bendel produced the 1981 newsstand special mentioned above. Several "True Facts" compilation books were published during the 1980s and early 90s, and several all-True-Facts issues of the magazine were published during the 1980s.

In the early 2000s, Steven Brykman edited the "True Facts" section of the National Lampoon website.

Foto Funnies

[edit]Most issues of the magazine featured one or more "Foto Funny" or fumetti, comic strips that use photographs instead of drawings as illustrations. The characters who appeared in the Lampoon's Foto Funnies were usually the male writers, editors, artists, photographers, or contributing editors of the magazine, often cast alongside nude or semi-nude female models. In 1980, a paperback compilation book, National Lampoon Foto Funnies which appeared as a part of National Lampoon Comics, was published.

Funny Pages

[edit]The "Funny Pages" was a large section at the back of the magazine that was composed entirely of comic strips of various kinds. These included work from a number of artists who also had pieces published in the main part of the magazine, including Gahan Wilson, Ed Subitzky and Vaughn Bodē, as well as artists whose work was only published in this section. The regular strips included "Dirty Duck" by Bobby London, "Trots and Bonnie" by Shary Flenniken, "The Appletons" and "Timberland Tales" by B. K. Taylor, "Politeness Man" by Ron Barrett, and many other strips. A compilation of Gahan Wilson's "Nuts" strip was published in 2011. The "Funny Pages" logo header art, which was positioned above Gahan Wilson's "Nuts" in each issue, and showed a comfortable, old-fashioned family reading newspaper-sized funny papers, was drawn by Michael Kaluta.

Corporate history

[edit]Twenty First Century Communications

[edit]The company that owned and published the magazine was called Twenty First Century Communications, Inc.. At the outset, Gerald L. "Jerry" Taylor was the magazine's publisher, followed by William T. Lippe. The business side was controlled by Matty Simmons, who was chairman of the board and CEO of Twenty First Century Communications.

1973–1975 creative and commercial zenith

[edit]The magazine was considered by many to be at its creative zenith in the period 1973–1975.[7] During this period, the magazine regularly published "special editions" which were sold simultaneously on newsstands. Some of the special editions were "best-of" omnibus collections; others were entirely original. Additional projects included a calendar, a songbook, a collection of transfer designs for T-shirts, and a number of books. From time to time, the magazine advertised Lampoon-related merchandise for sale, including specially-designed T-shirts. The magazine sold yellow binders with the Lampoon logo, designed to store a year's worth of issues.

It was also during this time that National Lampoon: Lemmings show was staged and The National Lampoon Radio Hour was broadcast, bringing interest and acclaim to the National Lampoon brand[7] with magazine talent like writer Michael O'Donoghue. Comedy stars John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Gilda Radner, Bill Murray, Brian Doyle Murray, Harold Ramis, and Richard Belzer first gained national attention for their performances in those productions.

1975 founders exit

[edit]In 1975, the three founders Kenney, Beard, and Hoffman left the magazine,[7] taking advantage of a buyout clause in their contracts for a shared total of $7.5 million[28] (although Kenney remained on the magazine's masthead as a senior editor until about 1976).

At about the same time, writers Michael O'Donoghue and Anne Beatts left NL to join Saturday Night Live, as did Chase, Belushi, and Radner, who left the troupe to join the original septet of SNL's Not Ready For Prime Time Players.[3][e] Bill Murray replaced Chase when Chase left SNL after the first season, and Brian Doyle Murray later appeared as an SNL regular.[30]

Harold Ramis went on to star in the Canadian sketch show SCTV and assumed the role as its head writer, then left after season 1 to be a prolific director, writer, and actor, working on such films as Animal House, Caddyshack, Ghostbusters, Groundhog Day and many more. Brian Doyle Murray has had roles in dozens of films, and Belzer was an Emmy Award-winning TV actor.

Heavy Metal / HM Communications

[edit]After a European trip in 1975 by Tony Hendra expressing interest in European comics, NL's New York offices attracted significant European comics material. In September 1976 editor Sean Kelly singled out the relatively new French anthology Métal hurlant (lit. 'Howling Metal', though Kelly translated it as "Screaming Metal")[31] and brought it to the attention of Twenty First Century Communications, Inc. president Leonard Mogel, who was departing for Germany and France to jump-start the French edition of National Lampoon.[32] Upon Mogel's return from Paris, he reported that the French publishers had agreed to an English-language version.[33]

Heavy Metal debuted in the US with an April 1977 issue, as a glossy, full-color monthly published by HM Communications, Inc., a subsidiary of Twenty First Century Communications, Inc.[34] The cover of the initial issue declared itself to be "From the people who bring you the National Lampoon", and the issue primarily featured reprints from Métal hurlant, as well as material from National Lampoon.[35] Since the color pages from Métal hurlant had already been shot in France, the budget to reproduce them in the US version was greatly reduced.[citation needed]

Animal House and shift of focus

[edit]In 1978, after the huge success of National Lampoon's Animal House, the company shifted focus from the magazine to NL-produced films. According to Tony Hendra, "...Matty Simmons decided this particular goose could lay larger, better quality gold eggs if it emulated what he saw as Animal House, by which he meant adolescent.... The significance of the choice that was made in 1978 cannot be underestimated."[7] In late 1979, now only publishing National Lampoon and Heavy Metal, Twenty First Century Communications, Inc. was renamed National Lampoon, Inc.[36]

From 1982 to 1985, the company produced five more National Lampoon films: National Lampoon's Class Reunion (1982), National Lampoon's Movie Madness (1982), National Lampoon's Vacation (1983), National Lampoon's Joy of Sex (1984), and National Lampoon's European Vacation (1985).

National Lampoon, Inc. made itself available for sale in late 1986. Upstart video distributor Vestron Inc. attempted a takeover bid in December of that year, but board members rejected the offer.[37] A short time later, the company board "agreed to be acquired by a Los Angeles-based group of private investors in a deal valued at more than $12 million."[38] The group, calling itself "N.L. Acquisitions Inc." offered a bid of $7.25 per share (the company stock at that point trading at $6.125 a share).[38] A few days later, "Giggle Acquisition Partnership No. 1," whose members included actor Bruce Willis, "hinted ... that it might make a hostile bid" for the company.[39] Ultimately, nothing came of these bids, and Simmons remained in control of the board.

In 1989, the company produced National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation.

Grodnik/Matheson takeover

[edit]In 1988–1989, the company was the subject of a hostile takeover. On December 29, 1988, film producer Daniel Grodnik and actor Tim Matheson (who played "Otter" in the magazine's first big hit, the 1978 film National Lampoon's Animal House) filed with the SEC that their production company, Grodnick/Matheson Co., had acquired voting control of 21.3 percent of National Lampoon Inc. stock and wanted to gain management control.[40] They were named to the company's board in January 1989, and eventually took control of the company by purchasing the ten-percent share of Simmons, who departed the company.[41][42]

Grodnik and Matheson became the co-chairmen/co-CEOs. During their tenure, the stock went up from under $2 to $6, and the magazine was able to double its monthly ad pages. The company moved its headquarters from New York to Los Angeles to focus on film and television. The publishing operation stayed in New York.[citation needed]

J2 Communications era

[edit]In 1990, Grodnik and Matheson sold the company (and more importantly, the rights to the brand name "National Lampoon") to J2 Communications (a company previously known for marketing Tim Conway's Dorf videos), headed by James P. Jimirro.[43][44][45] According to Jimirro, at that point, National Lampoon was "a moribund company that had been losing money since the early 1980s."[46] The property was considered valuable only as a brand name that could be licensed out to other companies.[2] The magazine itself was issued erratically and rarely from 1991 onwards; its final print publication was November 1998. (Meanwhile, in May 1992, J2 Communications sold Heavy Metal to cartoonist and publisher Kevin Eastman.)[47]

In 1991, J2 Communications began selling film rights to the "National Lampoon" name;[48] it was paid for the use of the brand on such films as National Lampoon's Loaded Weapon 1 (1993), National Lampoon's Senior Trip (1995), National Lampoon's Golf Punks (1998), National Lampoon's Van Wilder (2002), National Lampoon's Repli-Kate (2002), National Lampoon's Blackball (2003), and National Lampoon Presents: Jake's Booty Call (2003).[f] During this period, the company also licensed the Lampoon brand for five made-for-television movies, and one direct-to-video production. Although the licensing deals salvaged the company from bankruptcy,[46] many believe it damaged National Lampoon's reputation as a source of respected comedy.[7][2]

In 1998, the magazine contract was renegotiated and, in a sharp reversal, J2 Communications was then prohibited from publishing future issues.[2] J2, however, still owned the rights to the brand name, which it continued to franchise out to other users.[2]

National Lampoon Inc.

[edit]In 2002, the use of the Lampoon brand name and the rights to republish old material were sold[49] to a group of investors headed by Dan Laikin and Paul Skjodt. They formed a new, and otherwise unrelated, company called National Lampoon, Inc. Jimirro stayed on as CEO, serving until 2005.[2]

Laikin aimed to revive the brand's heyday spirit, engaging original contributors like Matty Simmons and Chris Miller. The company expanded, acquiring Burly Bear Network and initiating original programming. However, financial losses persisted, reaching millions annually. Amid chaotic office scenes, Laikin's inclusive hiring fostered camaraderie but struggled to attract top talent. Despite efforts to stabilize and relocate to Hollywood, financial woes persisted. Laikin stepped down in 2008, replaced by investor Tim Durham, who faced scrutiny for lavish spending and questionable tactics. Scandals plagued leadership, including Laikin's stock manipulation scheme and Durham's Ponzi scheme involvement. Legal battles ensued, culminating in first Laikin and then Durham's imprisonment.[2]

In 2012, Alan Donnes took over and revitalized the company, distancing it from controversies.[2]

PalmStar Media

[edit]PalmStar Media acquired National Lampoon in 2017. In 2020, National Lampoon sued its then-president, Evan Shapiro, for fraud, alleging in New York federal court that he owed more than $3 million for surreptitiously funneling the company's intellectual property and money from deals with Quibi, Disney+, and Comedy Central Digital into companies he controlled.[50] Shapiro later claimed that National Lampoon Co-CEO Kevin Frakes had bullied him out of a job.[51]

Related media

[edit]During its most active period, c. 1971–c. 1980, the magazine spun off numerous productions in a wide variety of media, including books, special issues, anthologies, and other print pieces:[52]

Special editions

[edit]- The Best of National Lampoon No. 1, 1971, an anthology

- The Breast of National Lampoon (a "Best of" No. 2), 1972, an anthology

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 3, 1973, an anthology, art directed by Michael Gross

- National Lampoon The Best of #4, 1973, an anthology, art directed by Gross

- The National Lampoon Encyclopedia of Humor, 1973, edited by Michael O'Donoghue and art directed by Gross.

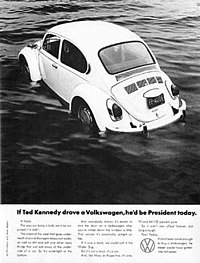

This publication featured the fake Volkswagen ad seen above, which was written by Anne Beatts. The spoof was listed in the contents page as "Doyle Dane Bernbach", the name of the advertising agency that had produced the iconic 1960s ad campaign for Volkswagen. According to Mark Simonson's "Very Large National Lampoon Site": "If you buy a copy of this issue, you may find the ad is missing. As a result of a lawsuit by VW over the ad for unauthorized use of their trademark, NatLamp was forced to remove the page (with razor blades!) from any copies they still had in inventory (which, from what I gather, was about half the first printing of 250,000 copies) and all subsequent reprints."[53] - National Lampoon Comics, an anthology, 1974, art directed by Gross and David Kaestle

- National Lampoon The Best of No. 5, 1974, an anthology, art directed by Gross and Kaestle

- National Lampoon 1964 High School Yearbook Parody, 1974, Edited by P.J. O'Rourke and Doug Kenney, art directed by Kaestle.[54]

- National Lampoon Presents The Very Large Book of Comical Funnies, 1975, edited by Sean Kelly

- National Lampoon The 199th Birthday Book, 1975, edited by Tony Hendra

- National Lampoon The Gentleman's Bathroom Companion, 1975 edited by Hendra, art directed by Peter Kleinman

- Official National Lampoon Bicentennial Calendar 1976, 1975, written and compiled by Christopher Cerf & Bill Effros

- National Lampoon Art Poster Book, 1975, Design direction by Peter Kleinman

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 6, 1976, an anthology

- National Lampoon The Iron On Book 1976, Original T-shirt designs, edited by Tony Hendra, art directed by Peter Kleinman.

- National Lampoon Songbook, 1976, edited by Sean Kelly, musical parodies in sheet music form

- National Lampoon The Naked and the Nude: Hollywood and Beyond, 1977, written by Brian McConnachie

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 7, 1977, an anthology

- National Lampoon Presents French Comics, 1977, edited by Peter Kaminsky, translators Sophie Balcoff, Sean Kelly, and Valerie Marchant

- National Lampoon The Up Yourself Book, 1977, Gerry Sussman

- National Lampoon Gentleman's Bathroom Companion 2, 1977, art directed by Peter Kleinman.

- National Lampoon The Book of Books, 1977 edited by Jeff Greenfield, art directed by Peter Kleinman

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 8, 1978, an anthology, Cover photo by Chris Callis, art directed by Peter Kleinman

- National Lampoon's Animal House Book, 1978, Chris Miller, Harold Ramis, Doug Kenney—art direction by Peter Kleinman and Judith Jacklin Belushi

- National Lampoon Sunday Newspaper Parody, 1978 (claiming to be a Sunday issue of the Dacron, Ohio (a spoof on Akron, Ohio) Republican–Democrat, this publication was originally issued in loose newsprint sections, mimicking a genuine American Sunday newspaper.) Art Direction and Design by Skip Johnston

- National Lampoon Presents Claire Bretécher, 1978, work by Claire Bretécher, French satirical cartoonist, 1978, Sean Kelly (editor), Translator Valerie Marchant

- Slightly Higher in Canada, 1978, Anthology of Canadian humor from National Lampoon. Sean Kelly and Ted Mann (Editors)

- Cartoons Even We Won't Dare Print, 1979, Sean Kelly and John Weidman (Editors), Simon and Schuster

- National Lampoon The Book of Books, 1979, Edited by Jeff Greenfield. Designed and Art Directed by Peter Kleinman

- National Lampoon Tenth Anniversary Anthology 1970–1980 1979 Edited by P.J. O'Rourke, art directed by Peter Kleinman

- National Lampoon Best Of #9: The Good Parts 1978-1980, 1981, the last anthology.

Books

[edit]- Beard, Henry, ed. (1972). Would You Buy a Used War from This Man?. Warner Paperback Library. ISBN 978-0446657983.

- McConnachie, Brian, ed. (1973). Letters from the Editors of National Lampoon. Warner Paperback Library. ISBN 978-0-446-75082-0.

- McConnachie, Brian; Kelly, Sean, eds. (1974). National Lampoon This Side of Parodies. Warner Paperback Library. ISBN 978-0446784283.

- McConnachie, Brian, ed. (1974). National Lampoon: The Paperback Conspiracy. Warner Paperback Library. ISBN 978-0446764308. Anthology.

- McConnachie, Brian, ed. (1974). The Job of Sex: a Workingman's Guide to Productive Lovemaking. Warner Paperback Library. ISBN 0446764299. OCLC 3107304.

- O'Rourke, P. J., ed. (1976). A Dirty Book!: Sexual Humor from the National Lampoon. Signet. ISBN 978-0451068996.

- O'Rourke, P. J.; Kaminsky, Peter; Cagan, Elsie, eds. (1976). Another Dirty Book!: Sexual Humor from the National Lampoon. Signet. ISBN 9780451085658.

- Weiner, Ellis (1984). National Lampoon's Doon. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-54144-7.

- 1981 National Lampoon True Facts, compiled by John Bendel—special edition

- 1982 National Lampoon Peekers & Other True Facts, by John Bendel—special edition

- Bendel, John, ed. (1991). National Lampoon Presents True Facts: The Book. Contemporary Press (now part McGraw-Hill). ISBN 978-0809240067.—"Amazing Ads, Stupefying Signs, Weird Wedding Announcements, and Other Absurd-but-True Samples of Real-Life Funny Stuff"

- Bendel, John, ed. (1992). National Lampoon Presents More True Facts: An All-New Collection of Absurd-But-True Real-Life Funny Stuff. Contemporary Press. ISBN 978-0809239429.

- Rubin, Scott, ed. (2004). National Lampoon's Big Book of True Facts: Brand-New Collection of Absurd-but-True Real-Life Funny Stuff. Rugged Land. ISBN 978-1590710296.

Recordings

[edit]Vinyl and cassette tapes

[edit]- 1972 National Lampoon Radio Dinner, 1972, produced by Tony Hendra

- 1973 Lemmings, an album of material taken from the stage show Lemmings, and produced by Tony Hendra

- 1974 The Missing White House Tapes, an album taken from the radio show, creative directors Tony Hendra and Sean Kelly

- 1975 National Lampoon Gold Turkey, creative director Brian McConnachie. Cover Photography by Chris Callis. Art Direction by Peter Kleinman

- 1975 National Lampoon Goodbye Pop 1952–1976, creative director Sean Kelly

- 1977 That's Not Funny, That's Sick, art-directed by Peter Kleinman. Illustrated by Sam Gross

- 1978 Original Motion Picture Soundtrack: National Lampoon's Animal House, soundtrack album from the movie

- 1978 Greatest Hits of the National Lampoon

- 1979 National Lampoon White Album

- 1982 Sex, Drugs, Rock 'N' Roll & the End of the World

Vinyl only

[edit]- 1974 Official National Lampoon Stereo Test and Demonstration Record, conceived by and written by Ed Subitzky

- 1972 "Deteriorata"—A snide parody, written by Tony Hendra, of Les Crane's 1971 hit "Desiderata"; it stayed on the lower reaches of the Billboard magazine charts for a month in late 1972. "Deteriorata" also became one of National Lampoon's best-selling posters.[citation needed]

- 1978 The galumphing theme to Animal House rose slightly higher and charted slightly longer in December 1978.

Cassette tape only

[edit]- 1980 The Official National Lampoon Car Stereo Test & Demonstration Tape, conceived and written by Ed Subitzky

CDs

[edit]- A single CD release, National Lampoon Gold Turkey recordings from The National Lampoon Radio Hour, was released by Rhino Records in 1996.

- A three-CD boxed set Buy This Box or We'll Shoot This Dog: The Best of the National Lampoon Radio Hour was released in 1996.

Many of the older albums that were originally on vinyl have been re-issued as CDs and a number of tracks from certain albums are available as MP3s.

Radio

[edit]- The National Lampoon Radio Hour was a nationally syndicated radio comedy show which was on the air weekly from 1973 to 1974. (For a complete listing of shows, see the National Lampoon Radio Hour Show Index.)[55]

Former Lampoon editor Tony Hendra later revived this format in 2012 for The Final Edition Radio Hour,[56] which became a podcast for National Lampoon, Inc. in 2015.

- True Facts, 1977–1978, written by and starring Peter Kaminsky, Ellis Weiner, Danny Abelson, Sylvia Grant

Theater

[edit]- 1973: Lemmings—National Lampoon's most successful theatrical venture. The off-Broadway production took the form of a parody of the Woodstock Festival. Co-written by Tony Hendra and Sean Kelly, and directed and produced by Hendra, it introduced John Belushi, Chevy Chase, and Christopher Guest in their first major roles. The show formed several companies and ran for a year at New York's Village Gate.

- 1974: The National Lampoon Show, with John Belushi, Brian Doyle-Murray, Bill Murray, Gilda Radner, and Harold Ramis; directed by Martin Charnin. Toured nationally in 1974, opened off-Broadway in 1975,[57] and toured nationally into 1976.[58]

- 1977–1978: That's Not Funny, That's Sick, toured the US and Canada,[58] later was the name of an NL album

- 1979: If We're Late, Start Without Us!, head writer Sean Kelly

- 1986: National Lampoon's Class of '86—performed at the Village Gate in 1986, aired on cable in the 1980s, and was subsequently available on VHS.

Television

[edit]- 1979 Delta House, Universal Television for ABC-TV[h]

- 1990 National Lampoon's Comedy Playoffs, Showtime Networks

Films

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2009) |

Considerable ambiguity exists about what actually constitutes a National Lampoon film.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, a few films were made as spin-offs from the original National Lampoon magazine, using its creative staff. The first theatrical release, and by far the most successful National Lampoon film was National Lampoon's Animal House (1978). Starring John Belushi and written by Doug Kenney, Harold Ramis, and Chris Miller, it became the highest-grossing comedy film of that time.[7] Produced on a low budget, it was so enormously profitable that, from that point on for the next two decades, the name "National Lampoon" applied to the title of a movie was considered to be a valuable selling point in and of itself.

Numerous movies were subsequently made that had "National Lampoon" as part of the title. Many of these were unrelated projects because, by that time, the name "National Lampoon" could simply be licensed on a one-time basis, by any company, for a fee. Critics such as the Orlando Sentinel's Roger Moore and The New York Times' Andrew Adam Newman[59] have written about the cheapening of the National Lampoon's movie imprimatur; in 2006, an Associated Press review said: "The National Lampoon, once a brand name above nearly all others in comedy, has become shorthand for pathetic frat boy humor."[59] (For the purpose of this article, only films made as spin-offs from the original National Lampoon magazine, using some of the magazine's creative staff to put together the outline and script, and/or were cast using actors from The National Lampoon Radio Hour and National Lampoon's Lemmings are considered.)

- National Lampoon's Animal House

In 1978, National Lampoon's Animal House was released. Made on a small budget, it did phenomenally well at the box office. In 2001, the United States Library of Congress considered the film "culturally significant" and preserved it in the National Film Registry.

The script had its origins in a series of short stories that had been previously published in the magazine. These included Chris Miller's "Night of the Seven Fires", which dramatized a fraternity initiation and included the characters Pinto and Otter, which contained prose versions of the toga party, the "road trip", and the dead horse incident. Another source was Doug Kenney's "First Lay Comics",[60] which included the angel and devil scene and the grocery-cart affair. According to the authors, most of these elements were based on real incidents.

The film was of great cultural significance to its time, as The New York Times describes the magazine's 1970s period as "Hedonism ... in full sway and political correctness in its infancy."[61] Animal House, as the article describes, was a crucial film manifestation of that culture. An article from The Atlantic describes how Animal House captures the struggle between an "elitist [fraternity] who willingly aligned itself with the establishment, and the kind full of kooks who refused to be tamed."[62] That concept was a crucial element of the original National Lampoon magazine, according to a New York Times article concerning its early years and co-founder Douglas Kenney's brand of comedy as a "liberating response to a rigid and hypocritical culture."[63]

- National Lampoon Goes to the Movies

Also known as National Lampoon's Movie Madness, this commercially disappointing collection of three genre parodies was made in 1981, before National Lampoon's Class Reunion but released the following year.

- National Lampoon's Class Reunion

This 1982 movie was an attempt by John Hughes to make something similar to Animal House. National Lampoon's Class Reunion was not successful.

- National Lampoon's Vacation

Released in 1983, the movie National Lampoon's Vacation was based upon John Hughes's National Lampoon story "Vacation '58".[64][65][66] The movie's financial success gave rise to several follow-up films, including National Lampoon's European Vacation (1985), National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation (1989), based on John Hughes's "Christmas '59", Vegas Vacation (1997), and most recently Vacation (2015), all featuring Chevy Chase.

Similar films

[edit]The Robert Altman film O.C. and Stiggs (1987) was based on two characters who had been featured in several written pieces in National Lampoon magazine, including an issue-long story from October 1982 entitled "The Utterly Monstrous, Mind-Roasting Summer of O.C. and Stiggs." Completed in 1984, the film was not released until 1987, when it was shown in a small number of theaters and without the "National Lampoon" name. It was not a success.

Following the success of Animal House, MAD magazine lent its name to a 1980 comedy titled Up the Academy. Although two of Animal House's co-writers were the Lampoon's Doug Kenney and Chris Miller, Up The Academy was strictly a licensing maneuver, with no creative input from Mad's staff or contributors. It was a critical and commercial failure.

Film about the magazine

[edit]In 2015, a documentary film was released called National Lampoon: Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead. The film featured a great deal of content from the magazine, as well as interviews with staff members and fans, and it explains how the magazine changed the course of humor.[67]

The 2018 film A Futile and Stupid Gesture, a biography of co-founder Douglas Kenney, also depicts the magazine's early years. The film was described by a 2018 New York Times article as a "snapshot of a moment where comedy's freshest counter-culture impulse was gleefully crass and willfully offensive." In the same article, Kenney was said to "spot a comical hollowness and rot in the society he and his peers were trained to join."[63]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The Harvard Lampoon established in 1876, was a long-standing tradition of the campus, influencing the later National Lampoon brand in its evolution from illustration-heavy publication to satirical wit, ranging from short fiction to comic strips.

- ^ The publishing industry's newsstand sales were excellent for many other magazines during that time: there were sales peaks for Mad (more than 2 million), Playboy (more than 7 million), and TV Guide (more than 19 million).[citation needed]

- ^ Former Lampoon editor Tony Hendra's book Going Too Far includes a series of precise circulation figures.[14]

- ^ "This month's superb cover idea was conceived by Ed Bluestone, and through skillful art direction and minimal interference from asshole editors, it became the tasteful entity you hold in your hands."[22]

- ^ As described in multiple sources, including the documentary Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead, Matty Simmons "didn't bite when NBC invited him to work on its planned Saturday night comedy show. This, of course, became Saturday Night Live."[29]

- ^ The company was not involved in Vegas Vacation (1997), the fourth installment in National Lampoon's Vacation film series. Vegas Vacation was the first theatrical Vacation film not to carry the National Lampoon label or a screenwriting credit from John Hughes. Also, it is the only National Lampoon film to be released in the 1990s, and the final film released before National Lampoon magazine folded.

- ^ There were also four all-"True-Facts" regular issues of the magazine, in 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1988.

- ^ Two derivative frat house projects, NBC's Brothers and Sisters and CBS' Co-Ed Fever, aired at the same time. None of the series were successful.

References

[edit]- ^ Carmody, Deirdre (December 5, 1990). "New Image Is Sought By Lampoon". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wallace, Benjamin (May 1, 2017). "Can Anyone Repair National Lampoon's Devastated Brand?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c Wayne, Teddy (October 29, 2013). "The Lowest Form of Humor: How the National Lampoon Shaped the Way We Laugh Now". The Millions.

- ^ Carney, Thomas (August 21, 1978). "They Only Laughed When It Hurt". New Times. pp. 48–55.

- ^ "Show Business: The Lampoon Goes Hollywood". Time. August 14, 1978.

- ^ Saura, Jennifer (November 19, 2010). "Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead Funny". Page-Turner. The New Yorker.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tapper, Jake (July 3, 2005). "National Lampoon Grows Up By Dumbing Down". The New York Times.

- ^ a b DOUGHERTY, PHILIP H. (November 24, 1969). "National Laughs for Lampoon: What Harvard boys have hopefully been chuckling about for 93 years will be offered in March to a nation much in need of a laugh or two". Advertising. The New York Times. p. 75.

- ^ a b c Dyess-Nugent, Phil (July 31, 2013). "How National Lampoon became the lost paradise and missing link of modern comedy". The A.V. Club.

- ^ White, Diane (March 11, 1970). "New publication is strictly for laughs". Boston Globe. p. 3.

The first issue, which is devoted entirely to sex, will go on sale Mar. 19.

- ^ a b Stein, Ellin (June 25, 2013). "Big and Glossy and Wonderful: The Birth of the 'National Lampoon' Magazine". Vulture. New York.

- ^ Simonson, Mark. "Introduction". Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site.

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #55—Pubescence". October 1974. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008 – via Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Website.

- ^ Hendra, Tony (1987). Going too Far: the Rise and Demise of Sick, Gross, Black, Sophomoric, Weirdo, Pinko, Anarchist, Underground, Anti-establishment Humor. Dolphin Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-23223-4.

- ^ a b c Hollie, Pamela G. (August 7, 1984). "SINGLE SUBJECT FOR LAMPOON". ADVERTISING. The New York Times.

- ^ "National Lampoon Cuts Back". Newswatch. The Comics Journal. No. 145. October 1991. p. 15.

- ^ "Lampoon adds Friedman, Drops Sex". Newswatch. The Comics Journal. No. 140. February 1991. p. 14.

- ^ "National Lampoon on Hiatus". Newswatch. The Comics Journal. No. 150. May 1992. p. 26.

- ^ "National Lampoon Returns Again". Newswatch. The Comics Journal. No. 158. April 1993. p. 25.

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #17—Bummer". August 1971. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #22—Is Nothing Sacred?". January 1972. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c "National Lampoon Issue #34—Death". January 1973. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ ASME Unveils Top 40 Magazine Covers Archived February 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ASME's Top 40 Magazine Covers of the Last 40 Years Archived February 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #52 - Dessert". July 1974. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Winters, Robert (July 1975). "National Lampoon 1975". National Lampoon Covers: 1970 - 1998.

- ^ Meyerowitz, Rick (September 1, 2010). Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Writers and Artists Who Made the National Lampoon Insanely Great (1st ed.). Amazon.com: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810988484.

- ^ Hendra, Tony (June 1, 2002). "Morning in America: the rise and fall of the National Lampoon". Harper's Magazine. (subscription required)

- ^ Voger, Mark (April 22, 2016). "National Lampoon's rise and fall". Jersey Retro: ENTERTAINMENT. NJ.com. NJ Advance Media.

- ^ Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle (2003). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946-Present (8 ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345455420.

- ^ "Screaming Metal". The Comics Journal. No. 94. October 1984. pp. 58–84.

- ^ Hendra, Tony; Kelly, Sean, eds. (March 1977). "Heavy Metal Preview". National Lampoon. National Lampoon Inc. pp. 91–102.

- ^ Lofficier, Jean-Marc (March 16, 1996). "Giving Credit to Mogel". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022.

- ^ "New Graphic Fantasy Magazine". Locus. Vol. 10, no. 2 (no. 199). February 1977. p. 1.

- ^ "Origins". Heavy Metal. No. 1. April 1977. p. 3.

- ^ Dougherty, Philip H. (September 12, 1979). "Advertising". New York Times. sec. D, p.12.

- ^ "Natl. Lampoon Nixes Takeover By Vestron". Variety. December 3, 1986. pp. 38, 40.

- ^ a b "Offer Accepted By Lampoon". COMPANY NEWS. New York Times. December 12, 1986.

- ^ "Group Weighs Lampoon Bid". COMPANY NEWS. The New York Times. December 17, 1986.

- ^ Farhi, Paul (December 30, 1988). "A Funny Twist for National Lampoon Inc". Archived from the original on February 1, 2022.

- ^ "An Actor Acquires Control of National Lampoon Inc". The New York Times. March 17, 1989. sec.D, p.5.

- ^ Delugach, Al (March 17, 1989). "Film Producers Matheson and Grodnik Buy Control of National Lampoon Inc". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022.

- ^ "J2 Buys Lampoon". The Comics Journal. No. 137. September 1990. p. 10.

- ^ Staff writer (March 10, 1990). "National Lampoon Acquisition Set". New York Times. sec.1, p.33.

- ^ McNary, Dave (October 26, 1990). "New owner takes over National Lampoon". United Press International. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022.

- ^ a b "National Lampoon's parent moves into black". UPI. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Eastman Buying Heavy Metal". Newswatch. The Comics Journal. No. 148. February 1992. p. 23.

- ^ "J2 Sells Lampoon Film Rights". Newswatch. The Comics Journal. No. 146. November 1991. p. 34.

- ^ "Chief of J2 Communications to Resign, Sell His Shares". Los Angeles Times. Bloomberg News. March 7, 2001. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015.

- ^ Albarazi, Hannah (November 6, 2020). "National Lampoon's $3M Fraud Suit Against Ex-Prez No Joke". Law360.

- ^ Berg, Lauren (December 10, 2020). "Ex-Nat'l Lampoon Prez Claims Execs, Attys Bullied Him". Law360.

- ^ "National Lampoon Books & Anthologies Index". Archived from the original on February 17, 2010.

- ^ Simonson, Mark (July 20, 1998). "28. VW Ad Parody". Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site.

- ^ Simonson, Mark (1974). "National Lampoon 1964 High School Yearbook Parody". Books & Anthologies. Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012.

- ^ "National Lampoon Radio Hour Show Index". Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Sokol, Tony (September 21, 2016). "Tony Hendra Takes The Heat for National Lampoon Radio Hour's Return: The Final Edition Radio Hour pulls the trigger on a thousand offenses, but don't shoot Tony Hendra over it". Den of Geek.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (March 3, 1975). "Stage: A New 'Lampoon': Audiences Hurrying to Be Insulted". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Siegel, Robert (July 21, 2011). "The Making of National Lampoon's Animal House". Blu-ray.com.

- ^ a b Newman, Andrew Adam (June 25, 2007). "National Lampoon Stakes Revival on Making Own Films". The New York Times.

- ^ "Mike Grell interview". The Silver Age Sage. Interviewed by B.D.S. 2009. Archived from the original on April 30, 2012.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (September 24, 2015). "Review: The Good Old Tasteless Days in 'Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead'". The New York Times.

- ^ Fetters, Ashley (February 28, 2014). "Pop Culture's War on Fraternities: Animal House and its many descendants didn't glorify the Greek system—they mocked it". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b Abebe, Nitsuh (February 22, 2018). "New Sentences: From 'A Futile and Stupid Gesture'". NEW SENTENCES. The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ Hughes, John (September 1979). "Vacation '58". National Lampoon. Twenty-First Century Communications.

- ^ THR STAFF (July 29, 2015). "Read John Hughes' Original National Lampoon Vacation Story That Started the Movie Franchise: In 1979, the magazine published the future director's fictitious tale of a family trip gone horribly awry ("If Dad hadn't shot Walt Disney in the leg, it would have been our best vacation ever"). Here, THR reprints the tale in full". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Hughes, John (2008). "Vacation '58 / Foreword '08". Zoetrope All-Story. American Zoetrope. Archived from the original on July 31, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Hunt, Robert (October 14, 2015). "How the National Lampoon Changed American Comedy, then Died". Riverfront Times.

Further reading

[edit]- Hendra, Tony (1987). Going Too Far: the Rise and Demise of Sick, Gross, Black, Sophomoric, Weirdo, Pinko, Anarchist, Underground, Anti-Establishment Humor. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-23223-4.

- Karp, Josh (2006). A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1-55652-602-4.

- Meyerowitz, Rick (2010). Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Writers and Artists Who Made National Lampoon Insanely Great. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-8848-4.

- Kennedy, Mopsy Strange (December 10, 1972). "Juvenile, puerile, sophomoric, jejune, nutty-and funny". The New York Times. pp. 447, 448, 510, 512, 514, 515.

- Perrin, Dennis (1998). Mr. Mike: The Life and Work of Michael O'Donoghue. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-97330-9.

- Simmons, Matty (1994). If You Don't Buy This Book, We'll Kill This Dog! Life, Laughs, Love, & Death at National Lampoon. New York: Barricade Books. ISBN 978-1-56980-002-7.

- Stein, Ellin (2013). That's Not Funny, That's Sick: The National Lampoon and the Comedy Insurgents Who Captured the Mainstream. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07409-3.

External links

[edit]- Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site

- Gallery of all National Lampoon covers, 1970-1998

- Gallery of art director Michael Gross' covers and art

- National Lampoon at the Grand Comics Database

- List of National Lampoon movies

- National Lampoon discography at Discogs

- Two-part interview with Anne Beatts, the Lampoon's first female contributing editor, on her involvement with the magazine: Part One | Part Two

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch