Grand Street Bridge

Grand Street Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 40°42′59″N 73°55′22″W / 40.716495°N 73.922748°W |

| Carries | Grand Street and Grand Avenue Q59 (New York City bus) Sidewalk |

| Crosses | Newtown Creek |

| Locale | Brooklyn and Queens, New York City |

| Maintained by | New York City Department of Transportation |

| ID number | 2240390 |

| Followed by | Kosciuszko Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Swing bridge with through-truss superstructure |

| Material | Steel superstructure and deck with masonry pier |

| Total length | 230 feet (70 m) |

| Width | 31.2 feet (9.5 m) |

| No. of spans | 1 |

| Clearance above | 13.4 feet (4.1 m) |

| Clearance below | 9.8 feet (3.0 m) MHW |

| No. of lanes | 2 |

| History | |

| Designer | New York City Department of Bridges |

| Construction start | August 1900 |

| Construction cost | $174,937 (equivalent to $6,160,474 in 2023) |

| Opened | December 26, 1902 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 10,213 (2016) |

| Location | |

| |

| References | |

| [1][2] | |

Grand Street Bridge (1890) | |

|---|---|

1896 map of Newtown Creek (Grand Street Bridge highlighted in red) | |

| Coordinates | 40°42′59″N 73°55′22″W / 40.716495°N 73.922748°W |

| Carries | Roadway and Brooklyn City Railroad (streetcar) |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Swing bridge |

| Material | Iron |

| Total length | 120 feet (37 m) |

| Width | 30 feet (9.1 m) |

| No. of spans | 1 |

| Rail characteristics | |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| History | |

| Designer | Dean & Westbrook |

| Constructed by | Charles A. Cregin |

| Construction start | 1889 |

| Construction end | July 30, 1890 |

| Replaces | Grand Street Bridge (original) |

| Replaced by | Grand Street Bridge (1903) |

Grand Street Bridge (1875) | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°42′59″N 73°55′22″W / 40.716495°N 73.922748°W |

| Carries | Roadway and Brooklyn City Railroad (streetcar) |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Swing bridge |

| No. of spans | 1 |

| Rail characteristics | |

| No. of tracks | 1 |

| History | |

| Construction end | 1875 |

| Replaced by | Grand Street Bridge (1890) |

Grand Street Bridge is a through-truss swing bridge over Newtown Creek in New York City. The current crossing was completed in 1902, and links Grand Street and Grand Avenue via a two-lane, height-restricted roadway. It is a main connection between the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, carrying an average of 10,200 vehicles per day (as of 2016[update]).[3]

History

[edit]According to the New York City Department of Transportation, three distinct swing bridges have spanned Newtown Creek at the location between Grand St. and Grand Avenue.[4] Up until the mid-20th century, the crossing also carried horse-drawn (and later, electrified) streetcars of the Grand Street and Newtown Railroad, which was later leased by Brooklyn City Railroad and eventually became the Brooklyn and Queens Transit Corporation.

Original bridge (1875)

[edit]One of the earliest references to a permanent crossing is found in an 1864 article from The Brooklyn Daily Times, reporting on the local Board of Aldermen's provision of $4,000 (equivalent to $77,923 in 2023) for the construction of a moveable bridge.[5] Based on sparse details, the first structure apparently featured a deck made of wooden planks and a single-track railroad.[6][7] It opened in 1875.[8]

Throughout the bridge's life, it was often found to be in a poor state of upkeep,[9] and local newspapers repeatedly wrote of its dangerous condition:[10]

The Grand street bridge, over Newtown Creek, which is maintained by Kings County and the Town of Newtown jointly, is almost in a useless condition. The machinery is so badly broken that the bridge can barely be turned by it. A Newtown paper, calling attention to this fact, says that it is about useless as a public convenience."

— The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 13, 1882

By 1889 the bridge was so deteriorated that on July 14, half of it "fell with a crash into the creek."[11] A year later, residents appeared to be questioning even the basic viability of bridges over Newtown Creek, with one Supervisor of Jamaica, Queens suggesting that the quadruple of Newtown's bridges be replaced with tunnels modeled after contemporary examples in Chicago. An editorial highlighted the claim that the initial cost of a "decently designed" drawbridge was no less than that of a tunnel, but a bridge would incur significantly higher maintenance, operation, and tending costs throughout its lifetime.[12]

Second bridge (1890)

[edit]In the fall of 1888, the Bridge Committee of the Supervisors of Kings and Queens Counties announced the exploration of replacement options for the original bridge.[13] After a request for proposal process which specified an iron bridge with either a stone or wooden substructure, a construction contract was awarded in July of the following year. The winner, Charles A. Cregin (employing a Dean & Westbrook design), was a native New Yorker who estimated a replacement cost of $60,750 (equivalent to $2,060,100 in 2023).[14][15]

Construction began in the summer of 1889, with expectations of the crossing being closed to road and rail traffic for nearly five months.[16] The project's completion was formally accepted by county Supervisors on July 30, 1890[17] at a final cost of around $70,000 (equivalent to $2,373,778 in 2023), including the bridge's rebuilt approaches.[18] Shortly after construction, an additional $850 (equivalent to $28,824 in 2023) was approved (controversially) to add a bridge-keeper's shelter.[19] On March 24, 1984, the bridge was electrified to enable trolley service.[20] Installed some time later, electrical machinery which could open and close the span in around "half a minute" was far more advanced than most of Brooklyn's other man-operated moveable bridges.[21]

While the new span was an improvement on its predecessor, the warm welcome would be short-lived. A significant controversy developed just eight years after its opening when local businessmen, represented by Congressman Charles G. Bennett, secured federal funding for dredging Newtown Creek to the tune of $275,000 (equivalent to $9,325,556 in 2023). While the new channel depth of 18 feet (5.5 m) was a boon to shipping interests, it also required reinforcement of the bridge foundation. This had the side-effect of narrowing each draw opening by 6 feet (1.8 m) and further-complicating the channel's geometry, making it unusable by vessels longer than 125 feet (38 m) LOA (i.e.– most of the freight vessels in operation on the creek at the time).

After receiving complaints from the area's maritime operators, the United States Department of War became involved in the dispute. The agency, which would soon gain federal authority over all domestic waterway navigability with Congress' passage of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899, notified the City of its position in a letter:[22]

"Whereas the Secretary of War has good reason to believe that the bridge over the East Branch of Newtown Creek, as Grand Street, Brooklyn, is an unreasonable obstruction to the free navigation of the said Newtown Creek, on account of the location of its piers and abutments and the narrowness of the draw opening, it is proposed to require the following changes to be made in the said bridge by April 1, 1900 to wit: The reconstruction of the bridge, with a width of forty feet, so as to make the west abutment not more than five feet beyond the harbor line, with a clear width of draw opening of not less than seventy-five feet, measured on the line of the bridge, and with the west abutment as far north and the east abutment as far south as the limits of the width of Grand Street will permit."

— United States Department of War, 1888

Citing a lack of funding for a replacement, the city's Department of Bridges desired to keep the crossing in place. At a hearing before the United States Army Corps of Engineers on January 17, 1889, Bridge Commissioner John L. Shea argued that his department had received no formal complaints,[23] and that the existing structure was better than no bridge at all. According to the department's Chief Engineer, "at any rate, they can only condemn the bridge. They cannot make us build another."[22]

Eventually, the weight of the federal government overpowered the city's resistance in a letter from the Secretary of War dated February 15, 1899. It mandated the previous proposal, effectively condemning the existing crossing. City Comptroller Bird Sim Coler was confident that funding could be secured for a replacement, since "the city could not afford to allow important highways to come in danger of being closed to all passage."[24]

Current bridge (1903)

[edit]On April 21, 1899, the New York City Board of Estimate under Mayor Robert Anderson Van Wyck authorized bonds worth $200,000 (equivalent to $6,782,222 in 2023) for construction of the third Grand Street Bridge.[25] According to a campaign ad, the measure was one of several concurrent public works in Brooklyn (including the Williamsburg Bridge) totaling over $14,904,000 (equivalent to $545,844,096 in 2023) worth of investment.[26]

Initial plans, drawn by the New York City Department of Bridges and approved by the Department of War on July 24, 1889, specified a steel through-truss superstructure with a masonry pier and abutments. The 195 feet (59 m) asymmetric span would provide a clear opening of 91 feet (28 m) on the western side of the channel and 55 feet (17 m) on the eastern side.[27][28] After a lengthy delay before the New York City Board of Aldermen, the bridge was granted final approval in December 1899.[29]

At some point in early 1900, the bridge's specifications were altered to extend the eastern portion of the span, ensuring an equal 91 feet (28 m) of clearance on both sides with a total span of around 230 feet (70 m).[30] Only two construction bids were received, and local contractor Bernard Rolf was awarded the project on July 23.[31] Work began in August with a projected timeline of 15 months,[32] but the project became plagued with labor strikes, material delays, and accusations by the Department of Bridges of contractor incompetence.[33] During construction, trolleys were detoured along Flushing and Metropolitan Avenues, and a temporary wooden footbridge stood alongside the crossing.[34] After a 13-month delay, the new bridge was finally completed under the direction of city engineers. In a stroke of irony, it opened on December 26, 1902, the very same day that its predecessor re-opened to the public, just downstream, in a second life as a temporary crossing supporting construction of the Vernon Avenue Bridge.[35]

While Newtown Creek (and the new bridge) saw heavy use by maritime traffic through the early and middle decades of the 20th century, a greater trend toward highway and rail transportation in the postwar era also correlated to fewer drawbridge openings as time progressed. According to NYCDOT data, Grand Street Bridge's opening frequency had fallen to fewer than 100 instances per year by 1997. Due to minimal usage, the Coast Guard amended federal regulations in 2000 to require a full 2 hours of advance notice for any Newtown Creek drawbridge openings.[36]

Incidents

[edit]Second bridge

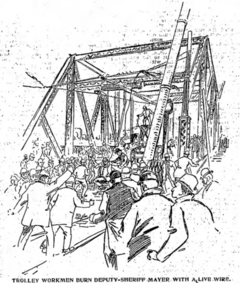

[edit]In the spring of 1894, a large fight broke out between county law enforcement and workers of the Brooklyn City Railroad when a construction permit dispute turned violent. According to a front-page report in The Standard Union newspaper, the railroad long-intended to install electrified trolley wires on the second Grand Street Bridge, but had failed to obtain permission from municipal engineers of Kings and Queens counties. Just before midnight on March 21, in defiance of local authorities, the railroad dispatched three work wagons and at least 60 men. The workmen swiftly overpowered the few sheriff's deputies who had been warned in advance, resulting in one officer injury and one worker being arrested in the tussle.[37]

While some of the installation was carried out later that night after the deputies retreated, the situation escalated severely on the morning of March 24.[38] When the railroad workers returned that Saturday, they were met with more sheriff's deputies from both Kings and Queens counties, who had been keeping watch all night.[39] A news article, paraphrased below, detailed what happened next:[20]

Anticipating that an attempt would be made to stop them, the workers had made their preparations accordingly. The railroad men had the wires on one of the tower trucks, and they connected these wires with the live trolley wires. Some of the men, all wearing rubber gloves to protect them from the live trolley wire, walked out on the bridge, drawing the wire after them. Deputy Philip Mayer stepped out on the structure to where the foreman of the gang was standing and ordered him to direct that the work be stopped. As soon as he did so, the man cried out: "Here, boys, roast the ––– ––– –––!" Immediately, one of the men carrying the live wire placed a coil of it around the neck of Deputy Mayer. The unfortunate man cried out in agony as the wire burned into his flesh. The deputy sheriffs were astounded at the action of the railroad men and determined to give up the fight.

— The Standard Union, March 24, 1894

When colleagues of Deputy Mayer attempted to assist his defense of the bridge, they reportedly injured the horses drawing the railroad's wagons across the span. Local constables of the Town of Newtown, sympathetic to the railroad, then arrested the deputies under the charge of animal abuse, after which a town judge held them to a bail bond of $300 (equivalent to $10,565 in 2023).[39] The trolley wires were ultimately completed, and the bridge continuously hosted rail service until the introduction of the B59 (now Q59) bus line in 1949.[40]

Current bridge

[edit]On December 9, 1902, three weeks before the current bridge officially opened, a tugboat captain was arrested for attempting to force open the structure using a hawser attached to his vessel.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 – Download NBI ASCII files – National Bridge Inventory – Bridge Inspection – Safety – Bridges & Structures – Federal Highway Administration". Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. 2016. p. 9. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ "Brooklyn – Queens Bridges ~ Average Daily Traffic Volumes" (PDF). 2016 New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes. NYCDOT: 97. 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "NYC DOT – Bridges – Newtown Creek". www1.nyc.gov. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Joint Board of Alderman and Supervisors". The Brooklyn Daily Times. August 9, 1864. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "Repairing and Replanking Grand Street Bridge Across a Branch of Newtown Creek". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 16, 1881. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "Near Resorts; Which may be easily reached from Brooklyn". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 6, 1885. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "New Grand Street Bridge". The Brooklyn Daily Times. August 15, 1901. p. 8. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Joint Board of Alderman and Supervisors". The Brooklyn Daily Times. August 9, 1864. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "City Hall Notes". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 23, 1872. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Bridge Gave Way" (PDF). The New York Times. July 14, 1889. p. 3. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Not One, but Four Tunnels". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 11, 1890. p. 2. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Grand Street Bridge". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 18, 1888. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Meyer, Henry C., ed. (July 20, 1889). "Contracting News – Bridges and Iron Structures". The Engineering & Building Record. XX (8): 110 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Cregin's Bid". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 18, 1889. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "The New Grand Street Bridge". The Brooklyn Daily Times. August 16, 1889. p. 4. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "To Tunnel Newtown Creek". The Brooklyn Daily Times. July 30, 1890. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "Good-bye to the Stench". The Brooklyn Daily Times. June 30, 1890. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "Supervisors Held a Very Breezy Annual Meeting Yesterday". The Standard Union. August 6, 1890. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ a b ""ROAST HIM!" – Deputy Sheriff burned by a live trolley wire". The Standard Union. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "Newtown Creek Bridges". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 18, 1897. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "Grand Street Bridge May be Condemned". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 1, 1899. p. 28. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Ask War Department to Condemn a Bridge". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 17, 1899. p. 2. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "City May Be Forced to Build New Bridges". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 27, 1899. p. 16. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Grand Street Bridge: Board of Estimate Authorizes Controller to Issue $200,000 of Bonds". The Brooklyn Citizen. April 22, 1899. p. 3. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Campaign Advertisement". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 25, 1899. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Grand Street Bridge". The Brooklyn Citizen. December 23, 1899. p. 2. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Bridges: Board of Estimate Asked to Authorize $950,000 for Two Over Newtown Creek". The Standard Union. February 27, 1899. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Bridges Still Held Up". The Brooklyn Citizen. December 30, 1899. p. 3. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Grand Street Bridge". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 11, 1900. p. 9. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Grand Street Bridge". The Brooklyn Citizen. July 23, 1900. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Work Started on New Bridge". The Standard Union. August 15, 1900. p. 5. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Brooklyn's Unlucky Bridges". The Standard Union. November 23, 1902. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Work Begun on New Bridge". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 27, 1900. p. 14. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Bridges Opened". The Brooklyn Daily Times. December 26, 1902. p. 4. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "33 CFR Part 117 – Drawbridge Operation Regulations: Newtown Creek, Dutch Kills, English" (PDF). Federal Register. 65 (148): 46870–46872. August 1, 2000. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ "LASSOED 'EM. – Railroad Employees Fight Supervisors and Officers". The Standard Union. March 23, 1894. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "They Used a Live Wire– Railroad Men Burn and Shock a Deputy Sheriff". The Brooklyn Citizen. March 24, 1894. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "Their Weapon a Live Wire: Trolley Workmen Burn a Deputy Sheriff on the Newtown Creek Bridge". The World. March 25, 1894. p. 7. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ "Public Notices". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 10, 1949. p. 21. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ "City News in Brief". The Brooklyn Daily Times. December 9, 1902. p. 4. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch