Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

| |

| Long title | An Act to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | INA of 1965 |

| Nicknames | Hart–Celler |

| Enacted by | the 89th United States Congress |

| Effective | December 1, 1965 July 1, 1968 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 89–236 |

| Statutes at Large | 79 Stat. 911 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 |

| Titles amended | 8 U.S.C.: Aliens and Nationality |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 8 U.S.C. ch. 12 (§§ 1101, 1151–1157, 1181–1182, 1201, 1254–1255, 1259, 1322, 1351) |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, was a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson.[1] The law abolished the National Origins Formula, which had been the basis of U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s.[2] The act formally removed de facto discrimination against Southern and Eastern Europeans as well as Asians, in addition to other non-Western and Northern European ethnicities from the immigration policy of the United States.[3]

The National Origins Formula had been established in the 1920s to preserve American homogeneity by promoting immigration from Western and Northern Europe.[2][4] During the 1960s, at the height of the civil rights movement, this approach increasingly came under attack for being racially discriminatory. The bill is based on the draft bill sent to the Congress by President John F. Kennedy, who opposed the immigration formulas, in 1963, and was introduced by Senator Philip Hart and Congressman Emanuel Celler.[5] However, its passage was stalled due to opposition from conservative Congressmen.[6]

With the support of the Johnson administration, Celler and Hart introduced the bill again in 1965 to repeal the formula.[7] The bill received wide support from both northern Democratic and Republican members of Congress, but strong opposition mostly from Southern conservatives, the latter mostly voting Nay or Not Voting.[8][9] President Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 into law on October 3, 1965.[1] Prior to the Act, the U.S. was 85% White, with Black people (most of whom were descendants of slaves) making up 11%, while Latinos made up less than 4%.[10] In opening entry to the U.S. to immigrants other than Western and Northern Europeans, the Act significantly altered the demographic mix in the country.[11]

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 created a seven-category preference system that gives priority to relatives and children of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents, professionals and other individuals with specialized skills, and refugees.[12] The act also set a numerical limit on immigration (120,000 per annum) from the Western Hemisphere for the first time in U.S. history.[13] Within the following decades, the United States would see an increased number of immigrants from Asia and Africa, as well as Eastern and Southern Europe.

Background

[edit]The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 marked a radical break from U.S. immigration policies of the past. Since Congress restricted naturalized citizenship to "white persons" in 1790, laws restricted immigration from Asia and Africa, and gave preference to Northern and Western Europeans over Southern and Eastern Europeans.[14][15] During this time, most of those immigrating to the U.S. were Northern Europeans of Protestant faith and Western Africans who were human trafficked because of American chattel slavery.[16] This pattern shifted in the mid to late 19th century for both the Western and Eastern regions of the United States. There was a large influx of immigration from Asia in the Western region—especially from China whose workers provided cheap labor—while Eastern and Southern European immigrants settled more in the Eastern United States.[17][18]

Once the demographics of immigration were changing, there were policies put in place to reduce immigration to exclude individuals of certain ethnicities and races. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to stop the inflow of Chinese immigrants.[19] Then in 1917, Congress passed the Immigration Act; this act had prevented most immigration of non-North Western Europeans because it tested language understanding.[2] This act was followed by the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, that placed a quota on immigration which used the rate of immigration in 1910 to mirror the immigration rate of all countries.[4] The Emergency Immigration Act of 1921 had helped bring along the Immigration Act of 1924 had permanently established the National Origins Formula as the basis of U.S. immigration policy, largely to restrict immigration from Asia, Southern Europe, and Eastern Europe. According to the Office of the Historian of the U.S. Department of State, the purpose of the 1924 Act was "to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity" by limiting immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.[20] The National Socialist Handbook for Law and Legislation of 1934–35, edited by the lawyer Hans Frank, contains a pivotal essay by Herbert Kier on the recommendations for race legislation which devoted a quarter of its pages to U.S. legislation, including race-based citizenship laws, anti-miscegenation laws, and immigration laws.[21] Adolf Hitler wrote of his admiration of America's immigration laws in Mein Kampf, saying:

The American Union categorically refuses the immigration of physically unhealthy elements, and simply excludes the immigration of certain races.[22]

In the 1960s, the United States faced both foreign and domestic pressures to change its nation-based formula, which was regarded as a system that discriminated based on an individual's place of birth. Abroad, former military allies and new independent nations aimed to de-legitimize discriminatory immigration, naturalization and regulations through international organizations like the United Nations.[23] In the United States, the national-based formula had been under scrutiny for a number of years. In 1952, President Truman had directed the Commission on Immigration and Naturalization to conduct an investigation and produce a report on the current immigration regulations. The report, Whom We Shall Welcome, served as the blueprint for the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.[24] At the height of the Civil Rights Movement the restrictive immigration laws were seen as an embarrassment.[11] At the time of the act's passing, many high-ranking politicians favored this bill to be passed, including President Lyndon B. Johnson.[25] However, only about half the public reciprocated these feelings, which can be seen in a Gallup Organization poll in 1965 asking whether they were in favor of getting rid of the national quota act, and 51 percent were in favor.[26] The act was pressured by high-ranking officials and interest groups to be passed, which it was passed on October 3, 1965.[27] President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1965 act into law at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, ending preferences for white immigrants dating to the 18th century.[14]

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 did not make it fully illegal for the United States government to discriminate against individuals, which included members of the LGBTQ+ community to be prohibited under the legislation.[14] The Immigration and Naturalization Service continued to deny entry to prospective immigrants who are in the LGBTQ+ community on the grounds that they were "mentally defective", or had a "constitutional psychopathic inferiority" until the Immigration Act of 1990 rescinded the provision discriminating against members of the LGBT+ community.[28]

Legislative history

[edit]

In 1958, senator John F. Kennedy or his team penned a pamphlet titled A Nation of Immigrants, opposing the immigration quotas set forth in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, after being convinced to do so by the Anti-Defamation League. The content of the pamphlet was based on the ideas of the historian Oscar Handlin and an outline by his student Arthur Mann, with Kennedy's version de-emphasizing the difficulties in assimilation of immigrants elucidated by Handlin and Mann, and promoting a more idealistic view. Immigration reform was promoted by Kennedy during his 1960 presidential campaign, with support from his brothers Robert F. Kennedy and Ted Kennedy.[5]

Following Kennedy's civil rights address in June 1963, he had Robert, who was the United States Attorney General, prepare a draft bill, which was authored by Adam Walinsky, and sent it to the Congress on July 23, 1963. The bill was introduced in the House of Representatives by Emanuel Celler, who had advocated for such an immigration reform since 1920s, and by Philip Hart in the Senate.[6] Ted was assigned to ensure the passage of the bill through the Congress.[5]

The act had a long history of trying to get passed by Congress. It had been introduced a number of times to the Senate between March 14, 1960, when it was first introduced,[citation needed] to August 19, 1965, which was the last time it was presented.[29] It was hard to pass this law under Kennedy's administration because Senator James Eastland (D-MS), Representative Michael Feighan (D-OH), and Representative Francis Walter (D-PA), who were in control of the immigration subcommittees, were against immigration reform.[7] When President Lyndon B. Johnson became president on January 8, 1964, he pressured Congress to act upon reform in immigration.[30] However, this president's support did not stop the debate of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 until January 4, 1965, when President Johnson focused his inaugural address on the reform of immigration, which created intense pressure for the heads of the congressional immigration subcommittees.[30]

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 in the 89th Congress

[edit]With the support of President Johnson's Administration, Representative Emanuel Celler (D-NY) introduced the Immigration and Nationality bill, H.R. 2580.[7] Emanuel Celler was a senior representative, as well as the Chair of the House Judiciary Committee.[31] When Celler introduced the bill, he knew that it would be hard for this bill to move from the committee to the floor successfully; the bill's committee was the Immigration and Nationality subcommittee.[7] The chair of the subcommittee was Representative Feighan, who was against immigration reform. In the end, a compromise was made where immigration based on familial reunification is more critical than immigration based on labor and skilled workers.[7] Later, Senator Philip Hart (D-MI) introduced the Immigration and Nationality bill, S.500, to the Senate.[7]

Congressional Hearings

[edit]During the subcommittee's hearing on Immigration and Naturalization of the Committee in the Judiciary United States Senate, many came forward to voice their support or opposition to the bill. Many higher-ranking officials in the executive and legislative branches, like Dean Rusk (Secretary of State) and Abba P. Schwartz (Administrator, Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State), came forward with active support.[32] Also, many cultural and civil rights organizations, like the Order Sons of Italy in America, and the Grand Council of Columbia Association in Civil Service, supported the act.[33] Many of the bill's supporters believed that this future would outlaw racism and prejudice rhetoric that previous immigration quotas have caused; this prejudice has also caused other nations to feel like the United States did not respect them due to their low rating in the previous immigration quotas.[32] Many also believed that this act would highly benefit the United States’ economy because the act focused on allowing skilled workers to enter the United States.[32]

On the other hand, many lobbyists and organizations, like the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Baltimore Anti-Communistic League, came to the hearing to explain their opposition.[33] Many of the opposition believed that this bill would be against American welfare. The common argument that they used was that if the government allowed more immigrants into the United States, more employment opportunities would be taken away from the American workforce.[33] While the farmers' organizations, like the American Farm Bureau Federation and the National Council of Agricultural, argued that this legislation would be hazardous for the agricultural industry due to the section regarding a limit of immigration of the Western Hemisphere.[33] Before this act, there was no limitation with the immigration of the Western Hemisphere, which allowed many migrant workers in the agricultural industry to easily move from countries in the Western Hemisphere to farms in the United States during critical farming seasons.[33] These agricultural organizations believed that this act could cause issues for migrant workers to enter the United States.[33]

The voting of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

[edit]Once the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed in the subcommittees and brought to floors of Congress, it was widely supported. Senator Philip Hart introduced the administration-backed immigration bill, which was reported to the Senate Judiciary Committee's Immigration and Naturalization Subcommittee.[34] Representative Emanuel Celler introduced the bill in the United States House of Representatives, which voted 320 to 70 in favor of the act, while the United States Senate passed the bill by a vote of 76 to 18.[34] In the Senate, 52 Democrats voted yes, 14 no, and 1 abstained. Among Senate Republicans, 24 voted yes, 3 voted no, and 1 abstained.[35] In the House, 202 Democrats voted yes, 60 voted no, and 12 abstained, 118 Republicans voted yes, 10 voted no, and 11 abstained.[36] In total, 74% of Democrats and 85% of Republicans voted for passage of this bill. Most of the no votes were from the American South, which was then still strongly Democratic. During debate on the Senate floor, Senator Ted Kennedy, speaking of the effects of the Act, said, "our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. ... Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset."[37]

Sen. Hiram Fong (R-HI) answered questions concerning the possible change in the United States' cultural pattern by an influx of Asians:

Asians represent six-tenths of 1 percent of the population of the United States ... with respect to Japan, we estimate that there will be a total for the first 5 years of some 5,391 ... the people from that part of the world will never reach 1 percent of the population ... Our cultural pattern will never be changed as far as America is concerned.

— U.S. Senate, Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization of the Committee on the Judiciary, Washington, D.C., Feb. 10, 1965, pp.71, 119.[38]

Democrat Rep. Michael A. Feighan (OH-20), along with some other Democrats, insisted that "family unification" should take priority over "employability", on the premise that such a weighting would maintain the existing ethnic profile of the country. That change in policy instead resulted in chain migration dominating the subsequent patterns of immigration to the United States.[39][40] In removing racial and national discrimination the Act would significantly alter the demographic mix in the U.S.[11]

When the act was on the floor, two possible amendments were created in order to impact the Western Hemisphere aspect of the legislation. In the House, the MacGregor Amendment was debated; this amendment called for the Western Hemisphere limit to be 115,000 immigrants annually. This amendment was rejected in a 189–218 record vote.[30] Then the act was pushed to the Senate, where a similar amendment was proposed (possibly creating a cap of 115,000 immigrants annually from the Western Hemisphere), but this was also never passed.[41][30]

Enactment

[edit]On October 3, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson officially signed the Immigration and Nationality Act. Because his administration believed that this was a historic legislation, he signed the act at Liberty Island, New York.[7] Upon signing the legislation into law, Johnson said, "this [old] system violates the basic principle of American democracy, the principle that values and rewards each man on the basis of his merit as a man. It has been un-American in the highest sense, because it has been untrue to the faith that brought thousands to these shores even before we were a country."[42]

Provisions

[edit]The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 amended the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (known as the McCarran–Walter Act). It upheld some provisions of the Immigration Act of 1924, while at the same time creating new and more inclusive immigration regulations. It maintained per-country limits, which had been a feature of U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s, and it developed preference categories.[43]

One of the main components of the act was aimed to abolish the national-origins quota. This meant that it eliminated national origin, race, and ancestry as a basis for immigration, making discriminating against obtaining visas illegal.[13]

It created a seven-category preference system. In this system, it explains how visas should be given out in order of most importance. This system prioritized individuals who were relatives of U.S. citizens, legal permanent resident, professionals, and/or other individuals with specialized skills.[13]

- The seven-category preference system is divided by family preferences and skill-based preferences. The family preferences include unmarried children of United States citizens, unmarried children and spouses of permanent residents, married children and their dependents of United States citizens, and siblings and their dependents of United States citizens. At the same time, the skilled preferences include individuals and their dependents who have extraordinary ability or significant knowledge in the arts, sciences, business, or entertainment; skilled workers in sectors facing labor shortages; investors willing to make large-sum investments in the U.S. economy; religious workers; and foreign nationals who have served in the U.S. military. Lastly, skilled-based preferences include the preferences for refugees.[13][44]

Immediate relatives and "special immigrants" were not subject to numerical restrictions. The law defined "immediate relatives" as children and spouses of United States citizens as well as parents of United States citizens who are 21 years of age or older.[13] It also defined "special immigrants" in six different categories, which includes:

- An immigrant who traveled abroad for a short period of time (i.e., a "Returning Resident");[13]

- An immigrant and dependents of the immigrant who is conducting religious practices and are needed by a religion sector to be in the United States.[13]

- An immigrant and their dependent who is/was a United States government employee abroad. They must have served 15 or more years to be considered a special immigrant. This category is only given if the Foreign Service Office recommended this specific immigrant to be qualified for this categorization.[13]

- An immigrant who is 14 years or younger has been considered an immediate relative of a U.S. citizen. However, their parent(s) cannot take care of them for multiple reasons, including death, abandonment, and so on.[13]

It added a quota system for immigration from the Western Hemisphere, which was not included in the earlier national quota system. This was for the first time, immigration from the Western Hemisphere was limited, while the Eastern Hemisphere saw an increase in the number of visas granted.[13] Previously, immigrants from Western Hemisphere countries needed merely to register themselves as permanent residents with a financial sponsor in the United States to avoid becoming public charges, and were not subject to skills-based requirements.

It added a labor certification requirement, which dictated that the Secretary of Labor needed to certify labor shortages in economic sectors for certain skills-based immigration statuses.[13]

Refugees were given the seventh and last category preference with the possibility of adjusting their status to permanent residents within one year of being granted refugee status. However, refugees could enter the United States by other means, such as seeking temporary asylum.[13]

The provisions of the 1794 Jay Treaty with the United Kingdom still apply, giving freedom of movement to Native Americans born in Canada.[45][46][47]

Immediate impact on quota immigrant admissions

[edit]

The Act of October 3, 1965, phased out the National Origins Formula quota system set by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 in two stages:

- Effective December 1, 1965, during a transition period covering fiscal years ending June 30 of 1966–1968, national quotas continued, but any unused quota spots were pooled and made available to other countries that had exhausted their quota, on a first-come, first-served basis.[48] While still granting first priority to European countries according to the National Origins Formula, immigration from countries with high quotas had slowed to far below maximum allotments. In 1965, 296,697 immigrants were admitted out of a total quota of 158,561.[48]

- Effective July 1, 1968, the national quota system was fully abolished, and the broad hemispheric numerical limitations took effect. All nation-level quotas were dropped and replaced by a limit of 170,000 immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere on a first-come, first-served basis, but while setting a cap of no more than 20,000 from any one country.[27] For the first time, immigration from within the Western Hemisphere was also restricted, legally capped at 120,000 annually.[27]

Listed below are quota immigrants admitted from the Eastern Hemisphere, by country, in given fiscal years ended June 30, for the final National Origins Formula quota year of 1965, the pool transition period 1966–1968, and for 1969–1970, the first two fiscal years in which national quotas were fully abolished.[49][50][51][52][53][54]

| Annual immigration to the United States | National Origins Formula[a] | Transition period[b] | Quotas abolished[c] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quota | % | 1965 | % | 1966 | % | 1968 | % | 1969 | % | 1970 | % | |

| Albania | 100 | 0.06% | 92 | 0.09% | 145 | 0.11% | 478 | 0.31% | 533 | 0.34% | 492 | 0.29% |

| Australia | 100 | 0.06% | 100 | 0.10% | 274 | 0.22% | 612 | 0.39% | 659 | 0.42% | 823 | 0.48% |

| Austria | 1,405 | 0.89% | 1,392 | 1.40% | 905 | 0.72% | 951 | 0.61% | 492 | 0.31% | 649 | 0.38% |

| Belgium | 1,297 | 0.82% | 1,015 | 1.02% | 784 | 0.62% | 594 | 0.38% | 251 | 0.16% | 334 | 0.19% |

| Bulgaria | 100 | 0.06% | 96 | 0.10% | 221 | 0.17% | 376 | 0.24% | 500 | 0.32% | 480 | 0.28% |

| Burma | 100 | 0.06% | 92 | 0.09% | 154 | 0.12% | 279 | 0.18% | 372 | 0.24% | 597 | 0.35% |

| China | 205 | 0.13% | 134 | 0.13% | 11,411 | 9.03% | 9,202 | 5.89% | 15,341 | 9.75% | 11,639 | 6.75% |

| Cyprus | 100 | 0.06% | 100 | 0.10% | 226 | 0.18% | 240 | 0.15% | 325 | 0.21% | 319 | 0.18% |

| Czechoslovakia | 2,859 | 1.80% | 1,965 | 1.98% | 1,415 | 1.12% | 1,456 | 0.93% | 3,051 | 1.94% | 4,265 | 2.47% |

| Denmark | 1,175 | 0.74% | 1,129 | 1.14% | 901 | 0.71% | 1,080 | 0.69% | 400 | 0.25% | 387 | 0.22% |

| Egypt (United Arab Republic) | 100 | 0.06% | 101 | 0.10% | 461 | 0.36% | 1,600 | 1.02% | 3,048 | 1.94% | 4,734 | 2.74% |

| Estonia | 115 | 0.07% | 85 | 0.09% | 91 | 0.07% | 67 | 0.04% | 34 | 0.02% | 37 | 0.02% |

| Finland | 566 | 0.36% | 540 | 0.54% | 377 | 0.30% | 572 | 0.37% | 190 | 0.12% | 352 | 0.20% |

| France | 3,069 | 1.94% | 3,011 | 3.03% | 2,283 | 1.81% | 2,788 | 1.78% | 1,323 | 0.84% | 1,874 | 1.09% |

| Germany | 25,814 | 16.28% | 21,621 | 21.76% | 14,461 | 11.45% | 9,557 | 6.12% | 3,974 | 2.53% | 4,283 | 2.48% |

| Greece | 308 | 0.19% | 233 | 0.23% | 4,906 | 3.88% | 10,442 | 6.68% | 15,586 | 9.91% | 14,301 | 8.29% |

| Hungary | 865 | 0.55% | 813 | 0.82% | 942 | 0.75% | 1,413 | 0.90% | 1,309 | 0.83% | 1,427 | 0.83% |

| Iceland | 100 | 0.06% | 95 | 0.10% | 62 | 0.05% | 78 | 0.05% | 106 | 0.07% | 173 | 0.10% |

| India | 100 | 0.06% | 99 | 0.10% | 1,946 | 1.54% | 4,061 | 2.60% | 5,484 | 3.49% | 9,712 | 5.63% |

| Indonesia | 200 | 0.13% | 200 | 0.20% | 214 | 0.17% | 455 | 0.29% | 712 | 0.45% | 710 | 0.41% |

| Iran | 100 | 0.06% | 101 | 0.10% | 331 | 0.26% | 724 | 0.46% | 902 | 0.57% | 1,265 | 0.73% |

| Iraq | 100 | 0.06% | 91 | 0.09% | 475 | 0.38% | 401 | 0.26% | 1,081 | 0.69% | 1,026 | 0.59% |

| Ireland | 17,756 | 11.20% | 5,256 | 5.29% | 3,068 | 2.43% | 2,587 | 1.66% | 1,495 | 0.95% | 1,199 | 0.69% |

| Israel | 100 | 0.06% | 101 | 0.10% | 411 | 0.33% | 1,229 | 0.79% | 1,832 | 1.16% | 1,626 | 0.94% |

| Italy | 5,666 | 3.57% | 5,363 | 5.40% | 18,955 | 15.01% | 17,130 | 10.97% | 18,262 | 11.61% | 19,759 | 11.45% |

| Japan | 185 | 0.12% | 181 | 0.18% | 677 | 0.54% | 1,098 | 0.70% | 1,594 | 1.01% | 1,755 | 1.02% |

| Jordan and Palestine | 200 | 0.13% | 196 | 0.20% | 687 | 0.54% | 1,366 | 0.87% | 2,120 | 1.35% | 2,345 | 1.36% |

| Korea | 100 | 0.06% | 111 | 0.11% | 528 | 0.42% | 1,549 | 0.99% | 2,883 | 1.83% | 5,056 | 2.93% |

| Latvia | 235 | 0.15% | 247 | 0.25% | 174 | 0.14% | 126 | 0.08% | 81 | 0.05% | 65 | 0.04% |

| Lebanon | 100 | 0.06% | 100 | 0.10% | 227 | 0.18% | 547 | 0.35% | 1,018 | 0.65% | 1,476 | 0.86% |

| Lithuania | 384 | 0.24% | 395 | 0.40% | 273 | 0.22% | 147 | 0.09% | 77 | 0.05% | 55 | 0.03% |

| Malta | 100 | 0.06% | 41 | 0.04% | 228 | 0.18% | 217 | 0.14% | 320 | 0.20% | 311 | 0.18% |

| Morocco | 100 | 0.06% | 96 | 0.10% | 145 | 0.11% | 270 | 0.17% | 468 | 0.30% | 330 | 0.19% |

| New Zealand | 100 | 0.06% | 88 | 0.09% | 122 | 0.10% | 234 | 0.15% | 264 | 0.17% | 321 | 0.19% |

| Netherlands | 3,136 | 1.98% | 3,132 | 3.15% | 2,242 | 1.78% | 2,179 | 1.39% | 1,097 | 0.70% | 1,357 | 0.79% |

| Norway | 2,364 | 1.49% | 2,237 | 2.25% | 1,584 | 1.25% | 1,173 | 0.75% | 485 | 0.31% | 346 | 0.20% |

| Pakistan | 100 | 0.06% | 99 | 0.10% | 256 | 0.20% | 588 | 0.38% | 761 | 0.48% | 1,406 | 0.81% |

| Philippines | 100 | 0.06% | 95 | 0.10% | 2,687 | 2.13% | 12,349 | 7.91% | 16,204 | 10.30% | 23,351 | 13.53% |

| Poland | 6,488 | 4.09% | 6,238 | 6.28% | 7,103 | 5.62% | 4,744 | 3.04% | 3,198 | 2.03% | 2,811 | 1.63% |

| Portugal | 438 | 0.28% | 428 | 0.43% | 7,163 | 5.67% | 11,444 | 7.33% | 15,836 | 10.07% | 12,627 | 7.32% |

| Romania | 289 | 0.18% | 294 | 0.30% | 1,090 | 0.86% | 675 | 0.43% | 1,074 | 0.68% | 1,533 | 0.89% |

| South Africa | 100 | 0.06% | 93 | 0.09% | 168 | 0.13% | 321 | 0.21% | 270 | 0.17% | 400 | 0.23% |

| Soviet Union | 2,697 | 1.70% | 2,707 | 2.72% | 1,748 | 1.38% | 950 | 0.61% | 777 | 0.49% | 698 | 0.40% |

| Spain | 250 | 0.16% | 251 | 0.25% | 982 | 0.78% | 1,741 | 1.11% | 2,551 | 1.62% | 3,005 | 1.74% |

| Sweden | 3,295 | 2.08% | 2,415 | 2.43% | 1,778 | 1.41% | 1,511 | 0.97% | 522 | 0.33% | 485 | 0.28% |

| Switzerland | 1,698 | 1.07% | 1,716 | 1.73% | 1,310 | 1.04% | 1,734 | 1.11% | 517 | 0.33% | 836 | 0.48% |

| Syria | 100 | 0.06% | 108 | 0.11% | 155 | 0.12% | 441 | 0.28% | 800 | 0.51% | 939 | 0.54% |

| Thailand | 100 | 0.06% | 89 | 0.09% | 88 | 0.07% | 266 | 0.17% | 542 | 0.34% | 602 | 0.35% |

| Turkey | 225 | 0.14% | 171 | 0.17% | 672 | 0.53% | 983 | 0.63% | 1,499 | 0.95% | 1,583 | 0.92% |

| United Kingdom | 65,361 | 41.22% | 29,923 | 30.11% | 23,721 | 18.78% | 33,550 | 21.48% | 14,962 | 9.51% | 15,133 | 8.77% |

| Vietnam | 100 | 0.06% | 97 | 0.10% | 104 | 0.08% | 94 | 0.06% | 174 | 0.11% | 248 | 0.14% |

| Yemen | 100 | 0.06% | 75 | 0.08% | 103 | 0.08% | 107 | 0.07% | 308 | 0.20% | 434 | 0.25% |

| Yugoslavia | 942 | 0.59% | 926 | 0.93% | 2,370 | 1.88% | 5,295 | 3.39% | 7,895 | 5.02% | 8,026 | 4.65% |

| Total from Europe | 149,697 | 94.41% | 94,128 | 94.71% | 102,197 | 80.91% | 116,210 | 74.39% | 98,480 | 62.60% | 98,939 | 57.34% |

| Total from Asia | 3,690 | 2.33% | 3,292 | 3.31% | 21,644 | 17.14% | 35,510 | 22.73% | 53,000 | 33.69% | 65,246 | 37.81% |

| Total from Africa | 4,274 | 2.70% | 1,332 | 1.34% | 1,658 | 1.31% | 3,321 | 2.13% | 4,586 | 2.92% | 6,736 | 3.90% |

| Total from all quota countries | 158,561 | 100.00% | 99,381 | 100.00% | 126,310 | 100.00% | 156,212 | 100.00% | 157,306 | 100.00% | 172,546 | 100.00% |

- ^ National Origins Formula quota system established by the Immigration Act of 1924, as amended under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (FY 1921-1965)

- ^ Effective December 1, 1965; unused quota spots pooled and made available to other countries (FY 1966-1968)

- ^ Effective July 1, 1968; national quotas replaced by broad hemispheric numerical limitations of 170,000 from the Eastern Hemisphere and 120,000 from Western Hemisphere (FY 1969-1990)

Wages under Foreign Certification

[edit]As per the rules under the Immigration and Nationality Act, U.S. organizations are permitted to employ foreign workers either temporarily or permanently to fulfill certain types of job requirements.[30][13] The Employment and Training Administration under the U.S. Department of Labor is the body that usually provides certification to employers allowing them to hire foreign workers in order to bridge qualified and skilled labor gaps in certain business areas. Employers must confirm that they are unable to hire American workers willing to perform the job for wages paid by employers for the same occupation in the intended area of employment. However, some unique rules are applied to each category of visas. They are as follows:

- H-1B and H-1B1 Specialty (Professional) Workers should have a pay, as per the prevailing wage – an average wage that is paid to a person employed in the same occupation in the area of employment; or that the employer pays its workers the actual wage paid to people having similar skills and qualifications.[55]

- H-2A Agricultural Workers should have the highest pay in accordance to the (a) Adverse Effect Wage Rate, (b) the present rate for a particular crop or area, or (c) the state or federal minimum wage. The law also stipulates requirements like employer-sponsored meals and transportation of the employees as well as restrictions on deducting from the workers' wages.[55]

- H-2B Non-agricultural Workers should receive a payment in accordance with the prevailing wage (mean wage paid to a worker employed in a similar occupation in the concerned area of employment).[55]

- D-1 Crewmembers (longshore work) should be paid the current wage (mean wage paid to a person employed in a similar occupation in the respective area of employment).[55]

- Permanent Employment of Aliens should be employed after the employer has agreed to provide and pay as per the prevailing wage trends. It should be decided on the basis of one of the many alternatives provisioned under the said Act. This rule has to be followed the moment the Alien has been granted with permanent residency or the Alien has been admitted to the United States to take the required position.[55]

Legacy

[edit]

The proponents of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 argued that it would not significantly influence United States culture. President Johnson said it was "not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions."[1] Secretary of State Dean Rusk and other politicians, including Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA), asserted that the bill would not affect the U.S. demographic mix.[11] However, following the passage of the law, the ethnic composition of immigrants changed,[56][57] altering the ethnic makeup of the U.S. with increased numbers of immigrants from Asia, Africa, the West Indies, and elsewhere in the Americas.[12] The 1965 act also imposed the first cap on total immigration from the Americas, marking the first time numerical limitations were placed on immigration from Latin American countries, including Mexico.[12][58] If the bill and its subsequent immigration waves since had not been passed, it is estimated by Pew Research that the U.S. would have been in 2015: 75% Non-Hispanic White, 14% Black, 8% Hispanic and less than 1% Asian.[59]

In the twenty years following passage of the law, 25,000 professional Filipino workers, including thousands of nurses, entered the U.S. under the law's occupational provision.[12]

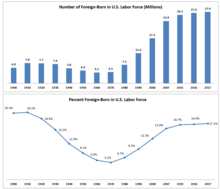

Family reunification under the law greatly increased the total number of immigrants, including Europeans, admitted to the U.S.; Between 1960 and 1975, 20,000 Italians arrived annually to join relatives who had earlier immigrated. Total immigration doubled between 1965 and 1970, and again between 1970 and 1990.[12] Immigration constituted 11 percent of the total U.S. population growth between 1960 and 1970, growing to 33 percent from 1970 to 1980, and to 39 percent from 1980 to 1990.[60] The percentage of foreign-born in the United States increased from 5 percent in 1965 to 14 percent in 2016.[61]

The elimination of the National Origins Formula and the introduction of numeric limits on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, along with the strong demand for immigrant workers by U.S. employers, led to rising numbers of illegal immigrants in the U.S. in the decades after 1965, especially in the Southwest.[62] Policies in the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 that were designed to curtail migration across the Mexico–U.S. border led many unauthorized workers to settle permanently in the U.S.[63] These demographic trends became a central part of anti-immigrant activism from the 1980s, leading to greater border militarization, rising apprehension of illegal immigrants by the Border Patrol, and a focus in the media on the criminality of illegal immigrants.[64][page needed]

The Immigration and Nationality Act's elimination of national and ethnic quotas has limited recent efforts at immigration restriction. In January 2017, President Donald Trump's Executive Order 13769 temporarily halted immigration from seven majority-Muslim nations.[65] However, lower federal courts ruled that the executive order violated the Immigration and Nationality Act's prohibitions of discrimination on the basis of nationality and religion. In June 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court overrode both appeals courts and allowed the second ban to go into effect, but carved out an exemption for persons with "bona fide relationships" in the U.S. In December 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the full travel ban—now in its third incarnation—to take effect, which excludes people who have a bona fide relationship with a person or entity in the United States.[66] In June 2018, the Supreme Court upheld the travel ban in Trump v. Hawaii, saying that the president's power to secure the country's borders, delegated by Congress over decades of immigration lawmaking, was not undermined by the president's history of arguably incendiary statements about the dangers he said some Muslims pose to the United States.[67]

See also

[edit]- Uniform Congressional District Act

- History of laws concerning immigration and naturalization in the United States

- Luce–Celler Act of 1946

- Remain in Mexico

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Johnson, L.B., (1965). President Lyndon B. Johnson's Remarks at the Signing of the Immigration Bill. Liberty Island, New York October 3, 1965 transcript at lbjlibrary Archived March 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Greenwood, Michael J.; Ward, Zachary (January 2015). "Immigration quotas, World War I, and emigrant flows from the United States in the early 20th century". Explorations in Economic History. 55: 76–96. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2014.05.001.

- ^ Hsu, Madeline Y. (2023), Lawrence, Mark Atwood; Updegrove, Mark K. (eds.), ""If I Cannot Get a Whole Loaf, I Will Get What Bread I Can": LBJ and the Hart–Celler Immigration Act of 1965", LBJ's America: The Life and Legacies of Lyndon Baines Johnson, Cambridge University Press, pp. 200–228, doi:10.1017/9781009172547.009, ISBN 978-1-009-17254-7

- ^ a b Massey, Catherine G. (April 2016). "Immigration quotas and immigrant selection". Explorations in Economic History. 60: 21–40. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2015.11.001.

- ^ a b c Godfrey Hodgson (2015). JFK and LBJ: The Last Two Great Presidents. Yale University Press. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-300-18242-2.

- ^ a b Patrick J. Hayes (2012). The Making of Modern Immigration An Encyclopedia of People and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. p. 449. ISBN 979-8-216-11373-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tichenor, Daniel (September 2016). "The Historical Presidency: Lyndon Johnson's Ambivalent Reform: The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: LBJ's Ambivalent Reform". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 46 (3): 691–705. doi:10.1111/psq.12300.

- ^ "TO PASS H.R. 2580, IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT AMENDMENTS. -- Senate Vote #232 -- Sep 22, 1965". GovTrack.us. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "TO AGREE TO THE CONFERENCE REPORT ON H.R. 2580, THE … -- House Vote #177 -- Sep 30, 1965". GovTrack.us. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "CCF Civil Rights Symposium: Changes in America's Racial and Ethnic Composition Since 1964". University of Texas. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Ludden, Jennifer (May 9, 2006). "1965 Immigration Law Changed Face of America". All Things Considered. NPR.

- ^ a b c d e Vecchio, Diane C. (2013). "U.S. Immigration Laws and Policies, 1870–1980". In Barkan, Elliott Robert (ed.). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration, Volume 4. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1498–9. ISBN 978-1-59884-219-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, 8 U.S.C. § 1101 (1965)

- ^ a b c "The Immigration Act of 1965 and the Creation of a Modern, Diverse America". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Immigration Before 1965". History. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Immigration Before 1965". HISTORY. September 10, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Immigration Before 1965". HISTORY. September 10, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Kanazawa, Mark (September 2005). "Immigration, Exclusion, and Taxation: Anti-Chinese Legislation in Gold Rush California". The Journal of Economic History. 65 (3): 779–805. doi:10.1017/s0022050705000288 (inactive November 1, 2024). JSTOR 3875017. S2CID 154316126.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Kil, Sang Hea (November 2012). "Fearing yellow, imagining white: media analysis of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882". Social Identities. 18 (6): 663–677. doi:10.1080/13504630.2012.708995. S2CID 143449924.

- ^ "Milestones: 1921–1936: The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act)". Office of the Historian, United States Department of State. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Whitman, James Q. (2017). Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press. pp. 37–43.

- ^ "American laws against 'coloreds' influenced Nazi racial planners". The Times of Israel. Retrieved August 26, 2017

- ^ "The Geopolitical Origins of the U.S. Immigration Acts of 1965". migrationpolicy.org. February 4, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ "Whom we shall welcome; report". archive.org. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ Times, Charles Mohrspecial To the New York (January 14, 1965). "PRESIDENT ASKS ENDING OF QUOTAS FOR IMMIGRANTS; Message to Congress Seeks Switch Over 5 Years to a Preferential System SKILLED GIVEN PRIORITY Program Would Also Help Relatives of Citizens and Drop Curbs on Asians PRESIDENT OFFERS IMMIGRANT PLAN". The New York Times. ProQuest 116778624.

- ^ "Roper iPoll by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research".

- ^ a b c Hatton, Timothy J. (April 2015). "United States Immigration Policy: The 1965 Act and its Consequences" (PDF). The Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 117 (2): 347–368. doi:10.1111/sjoe.12094. S2CID 154641063.

- ^ Davis, Tracy (1999). "Opening the Doors of Immigration: Sexual Orientation and Asylum in the United States". Human Rights Brief. 6 (3).

- ^ Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, 8 U.S.C. § 1101 et seq. (1965).

- ^ a b c d e Marinari, Maddalena (April 2014). "'Americans Must Show Justice in Immigration Policies Too': The Passage of the 1965 Immigration Act". Journal of Policy History. 26 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1017/S0898030614000049. S2CID 154720666.

- ^ Lyons, Richard L. (January 16, 1981). "Former Rep. Emanuel Celler Dies". Washington Post.

- ^ a b c Immigration. Part 1, 89 Cong. (1965).

- ^ a b c d e f Immigration. Part 2, 89 Cong. (1965).

- ^ a b Association of Centers for the Study of Congress. "Immigration and Nationalization Act". The Great Society Congress. Association of Centers for the Study of Congress. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Poole, Keith. "Senate Vote #232 (Sep 22, 1965)". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ Poole, Keith. "House Vote #177 (Sep 30, 1965)". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ Bill Ong Hing (2012), Defining America: Through Immigration Policy, Temple University Press, p. 95, ISBN 978-1-59213-848-7

- ^ "The Legacy of the 1965 Immigration Act". CIS.org. September 1995.

- ^ Tom Gjelten, Laura Knoy (January 21, 2016). NPR's Tom Gjelten on America's Immigration Story (Radio broadcast). The Exchange. New Hampshire Public Radio. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Gjelten, Tom (August 12, 2015). "Michael Feighan and LBJ". Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ John Little McClellan (AL). "S.2364." Congressional Record 111 (1965) p. 24557. (Text from: Congressional Record Permanent Digital Collection); Accessed: October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Remarks at the Signing of the Immigration Bill, Liberty Island, New York". October 3, 1965. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Keely, Charles B. (1979). "The Development of U.S. Immigration Policy Since 1965". Journal of International Affairs. 33 (2): 249–263. JSTOR 24356284. ProQuest 1290509526.

- ^ Lee, Catherine (June 2015). "Family Reunification and the Limits of Immigration Reform: Impact and Legacy of the 1965 Immigration Act". Sociological Forum. 30 (S1): 528–548. doi:10.1111/socf.12176.

- ^ "First Nations and Native Americans". United States Embassy, Consular Services Canada. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ Karl S. Hele, Lines Drawn upon the Water: First Nations and the Great Lakes Borders and Borderlands (2008) p. 127

- ^ "Border Crossing Rights Under the Jay Treaty". Pine Tree Legal Assistance. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau (1981). Immigration and Naturalization. Retrieved from https://www2.census.gov/prod2/statcomp/documents/1981-03.pdf

- ^ "Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1966" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States ...: Finance, Coinage, Commerce, Immigration, Shipping, the Postal Service, Population, Railroads, Agriculture, Coal and Iron (87th ed.). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census: 89–93. July 1966. ISSN 0081-4741. LCCN 04-018089. OCLC 781377180. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER OF IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION" (PDF) (1965 ed.). WASHINGTON, D.C: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE. June 1966. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER OF IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION" (PDF) (1966 ed.). WASHINGTON, D.C: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE. June 1967. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER OF IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION" (PDF) (1968 ed.). WASHINGTON, D.C: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE. June 1969. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER OF IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION" (PDF) (1969 ed.). WASHINGTON, D.C: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE. June 1970. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1970" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States ...: Finance, Coinage, Commerce, Immigration, Shipping, the Postal Service, Population, Railroads, Agriculture, Coal and Iron (91st ed.). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census. July 1970. ISSN 0081-4741. LCCN 04-018089. OCLC 781377180. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Wages under Foreign Labor Certification". U.S. Department of Labor. Archived from the original on September 25, 2005. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ Ngai, Mae M. (2004). Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 266–268. ISBN 978-0-691-16082-5.

- ^ Law, Anna O. (Summer 2002). "The Diversity Visa Lottery – A Cycle of Unintended Consequences in United States Immigration Policy". Journal of American Ethnic History. 21 (4): 3–29. doi:10.2307/27501196. JSTOR 27501196. S2CID 254481556. Gale A403786039.

- ^ Wolgin, Philip (October 16, 2015). "The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 Turns 50". Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065". Pew Research Center's Hispanic Trends Project. September 28, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Lind, Michael (1995). The Next American Nation: The New Nationalism and the Fourth American Revolution. New York: The Free Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-684-82503-8.

- ^ "Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065". Pew Research Center. September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Massey, Douglas S. (September 25, 2015). "How a 1965 immigration reform created illegal immigration". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Massey, Douglas S.; Durand, Jorge; Pren, Karen A. (March 2016). "Why Border Enforcement Backfired". American Journal of Sociology. 121 (5): 1557–1600. doi:10.1086/684200. PMC 5049707. PMID 27721512.

- ^ Chavez, Leo (2013). The Latino Threat: Constructing immigrants, citizens, and the nation (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-8352-1.

- ^ See Wikisource:Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States

- ^ Lydia Wheeler (December 4, 2017). "Supreme Court allows full Trump travel ban to take effect". The Hill.

- ^ "Trump's Travel Ban is Upheld by Supreme Court". The New York Times. June 26, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Chin, Gabriel (November 1996). "The Civil Rights Revolution Comes to Immigration Law: A New Look at the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965". North Carolina Law Review. 75 (1): 273. SSRN 1121504.

- Chin, Gabriel J., and Rose Cuison Villazor, eds. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: legislating a new America (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- LeMay, Michael C. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: A Reference Guide (ABC-CLIO, 2020).

- Orchowski, Margaret Sands. The law that changed the face of America: the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

- Tichenor, Daniel (September 2016). "The Historical Presidency: Lyndon Johnson's Ambivalent Reform: The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: LBJ's Ambivalent Reform". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 46 (3): 691–705. doi:10.1111/psq.12300.

- Zolberg, Aristide R. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (2008)

External links

[edit]- 8 USC Chapter 12 of the United States Code from LII

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 as amended (PDF/details) in the GPO Statute Compilations collection

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 as enacted (79 Stat. 911) in the US Statutes at Large

- 8 CFR Subchapter B of the CFR from LII

- 8 CFR Subchapter B of the CFR from the OFR

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

- Immigration Policy in the United States (2006), Congressional Budget office.

- The Great Society Congress

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch