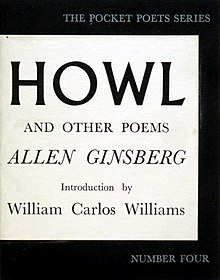

Howl and Other Poems

Howl and Other Poems is a collection of poetry by Allen Ginsberg published November 1, 1956. It contains Ginsberg's most famous poem, "Howl", which is considered to be one of the principal works of the Beat Generation as well as "A Supermarket in California", "Transcription of Organ Music", "Sunflower Sutra", "America", "In the Baggage Room at Greyhound", and some of his earlier works. For printing the collection, the publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti, another well-known poet, was arrested and charged with obscenity.[1] On October 3, 1957, Judge Clayton W. Horn found Ferlinghetti not guilty of the obscenity charge, and 5,000 more copies of the text were printed to meet the public demand, which had risen in response to the publicity surrounding the trial.[1] Howl and Other Poems contains two of the most well-known poems from the Beat Generation, "Howl" and "A Supermarket in California", which have been reprinted in other collections, including the Norton Anthology of American Literature.

The collection was initially dedicated to Lucien Carr but, upon Carr's request, his name was later removed from all future editions.[2]

Publication history

[edit]Lawrence Ferlinghetti offered to publish "Howl" through City Lights soon after hearing Ginsberg perform it at the Six Gallery Reading.[1] Ferlinghetti was so impressed, he sent a note to Ginsberg, referencing Ralph Waldo Emerson's response to Leaves of Grass: "I greet you at the beginning of a great career. When do I get the manuscript?"[3] Originally, Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti assumed "Howl" would be long enough to take up the entire book,[4] but they later decided to add some similar poems Ginsberg had completed around that time.[5]

The "Other Poems"

[edit]

Though "Howl" was Ginsberg's most famous poem, the collection includes many examples of Ginsberg at his peak, many of which garnered nearly as much attention and praise as "Howl." These poems include:

"America"

[edit]"America" is a poem in a conversation form between the narrator and America. When the narrator says "It Occurs to me that I am America", he follows with "I am talking to myself again." The tone is generally humorous and often sarcastic though the subject is often quite serious. He references several heroes and martyrs of significant movements such as the labor movement. These include: Leon Trotsky, the Scottsboro Boys, Sacco and Vanzetti, and Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World members). He includes several events of personal significance including his Uncle Max coming over from Russia, William S. Burroughs living in Tangier, and how his mother, Naomi, would take him to Communist meetings when he was seven. "America" can be seen as a continuation of the experiment he started with the long line and fixed base of "Howl." Ginsberg said, "What happens if you mix long and short lines, single breath remaining the rule of measure? I didn't trust free flight yet, so went back to fixed base to sustain the flow, 'America'."[6]

"A Supermarket in California"

[edit]"A Supermarket in California" is a short poem about a dreamlike encounter with Walt Whitman, one of Ginsberg's biggest idols. The image of Whitman is contrasted with mundane images of a supermarket, food often being used for sexual puns. He references Federico García Lorca whose "Ode to Walt Whitman" was an inspiration in writing "Howl" and other poems. In relation to his experiments with "Howl", Ginsberg says this: "A lot of these forms developed out of an extreme rhapsodic wail I once heard in a madhouse. Later I wondered if short quiet lyrical poems could be written using the long line. A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley and A Supermarket in California (written same day) fell in place later that year. Not purposely, I simply followed my angel in the course of compositions".[6]

"Sunflower Sutra"

[edit]"Sunflower Sutra" is an account of a sojourn with Jack Kerouac in a railroad yard, the discovery of a sunflower covered in dirt and soot from the railroad yard, and the subsequent revelation that this is a metaphor for all humanity: "we are not our skin of grime." This relates to his vision/auditory hallucination of poet William Blake reading "Ah, Sunflower": "Blake, my visions." (See also line in Howl: "Blake-light tragedies" and references in other poems). The theme of the poem is consistent with Ginsberg's revelation in his original vision of Blake: the revelation that all of humanity was interconnected. (See also the line in "Footnote to Howl": "The world is holy!"). The structure of this poem relates to "Howl" both in its use of the long line and its repetition of the "eyeball kick" (paratactical juxtapositions) at the end. Ginsberg says in relating his thought process after the experiments of "Howl," "What about a poem with rhythmic buildup power equal to Howl without use of repetitive base to sustain it? The Sunflower Sutra ... did that, it surprised me, one long who."[6]

"Transcription of Organ Music"

[edit]"Transcription of Organ Music" is an account of a quiet moment in his new cottage in Berkeley, nearly empty, not yet fully set up (Ginsberg being too poor, for example, to get telephone service). The poem contains repeated images of opening or being open: open doors, empty sockets, opening flowers, the open womb, leading to the image of the whole world being "open to receive." The "H.P." in the poem is Helen Parker, one of Ginsberg's first girlfriends; they dated briefly in 1950. The poem ends on a Whitman-esque note with a confession of his desire for people to "bow when they see" him and say he is "gifted with poetry" and has seen the creator. This may be seen as arrogance, but Ginsberg's arrogant statements can often be read as tongue-in-cheek (see for example "I am America" from "America" or the later poem "Ego Confessions"). However, this could be another example of Ginsberg trying on the Walt Whitman persona (Whitman who, for example, called himself a "kosmos" partly to show the interconnectedness of all beings) which would become so integral to his image in later decades. Ginsberg says this of his mind frame when composing "Transcription of Organ Music", in reference to developing his style after his experiments with "Howl": "What if I just simply wrote, in long units and broken short lines, spontaneously noting prosaic realities mixed with emotional upsurges, solitaries? Transcription of Organ Music (sensual data), strange writing which passes from prose to poetry and back, like the mind".[7]

Other poems

[edit]- "In the Baggage Room at Grey Hound"

- Some editions also include earlier poems, such as: "Song," "In Back of the Real," "Wild Orphan," "An Asphodel," etc.

Criticism

[edit]In American Scream, Jonah Raskin explores Ginsberg's "conspiratorial" themes in Howl, suggesting that Ginsberg, more than any other 20th-Century American poet, used literature to vent his criticism of the American government's treatment of the people and the diabolic actions of the CIA during the Cold War.[8] Ginsberg claimed that the CIA was partially responsible for his rejection by publishers, an accusation that Raskin suggests might have carried merit, even as there was no tangible evidence supporting the theory. Having discussed the issue with Ginsberg himself, Raskin writes:

Who were the CIA-sponsored intellectuals? I asked Ginsberg when we talked in Marin in 1985. Lionel Trilling, Norman Podhoretz, and Mary McCarthy, he replied. In his eyes they contributed to the unhealthy climate of the Cold War as much as the cultural commissars behind the Iron Curtain did.[8]

David Bergman, in Camp Grounds describes Ginsberg as a poet who, while not addressing the need to support the homosexual community directly, used a "Comically carnivalesque" tone to paint a picture of the situation facing the homosexual in 20th-Century society.[9] As the poet in "Supermarket in California" addresses the grocery boy by saying "Are you my Angel?", Bergman suggests that the questions are rhetorical and meant to point out the relationship between the poet and popular culture by using the market as a "symbol of petit bourgeois society".

Gary Snyder, who traveled with Ginsberg and was present during the first public readings of Howl, stated that the poem suffered from the fact that it was meant as a personal statement. In his letters, Snyder argued that the poem contained repetitions of familiar dualisms that were not present in other works by Ginsberg during the era.[10] However, in an interview published February 12, 2008, Snyder discussed the beneficial aspects of the poem and its reflection of society as it appeared to both Ginsberg and the public: "He was already very much at home in the text, and it clearly spoke -- as everyone could see -- to the condition of the people".[11]

Literary critic Diana Trilling criticized Ginsberg along with his audience by suggesting that "Howl" and other Ginsberg works presented an immature view of the modern society. To Trilling, the audience and Ginsberg shared a relationship that had little to do with literature, and she writes that the "Shoddiness" of the poems attested to the fact that they were created to relate to cynical popular culture rather than provide an artistic statement.[12] Along with others in the Beat generation, the popularity of Howl attracted criticism on the tone and style of the Beat poets. Norman Podhoretz, in a 1958 article entitled "The Know-Nothing Bohemians", writes that "the plain truth is that the primitivism of the Beat Generation serves first of all as a cover for an anti-intellectualism so bitter that it makes the ordinary American's hatred of eggheads seem positively benign".[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Morgan, Bill and Joyce Peters. Howl on Trial. (2006) p.xiii.

- ^ "The Last Beat". Columbia Magazine.

- ^ Barry Miles. Ginsberg: A Biography. Virgin Publishing Ltd., 2000. 0753504863. pg. 194.

- ^ Miles, pg. 190.

- ^ Edited by Matt Theado. The Beats: A Literary Reference. Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0-7867-1099-3. pg. 242.

- ^ a b c Ginsberg, Allen; Hyde, Lewis (1984). "Notes Written on Finally Recording Howl". On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg. University of Michigan Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-472-06353-7.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen. "Notes Written on Finally Recording 'Howl.'" Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952-1995. Ed. Bill Morgan. NY: HarperCollins, 2000.

- ^ a b Raskin, Jonah. American Scream. U of California P. (2006) p. xiii.

- ^ Bergman, David. Camp Grounds.U of Mass P (1983) p.104.

- ^ Snyder, Gary. qtd in Strange Prophecies Anew by Tony Trigilio. pp.49-50.

- ^ Snyder, Gary. Qtd in "Gary Snyder on hitchhiking and "Howl" at Reed". Jeff Baker. The Oregonian. Feb 12, 2008.

- ^ Trilling, Diana. qtd. in Prodigal Sons by Alexander Bloom. Oxford U P (1986)p.302

- ^ Podhoretz, Norman. "The Know-Nothing Bohemians". Partisan Review XXV Ed. 2 (1958)

External links

[edit]- Allen Ginsberg.org

- Allen Ginsberg on Poets.org With audio clips, poems, and related essays, from the Academy of American Poets

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch