Inchicore

Inchicore Irish: Inse Chór | |

|---|---|

Suburb | |

Inchicore, Dublin | |

| Coordinates: 53°20′06″N 6°19′55″W / 53.335°N 6.332°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | Dublin |

| City | Dublin (Dublin City Council) |

| Government | |

| • Dáil Éireann | Dublin South-Central |

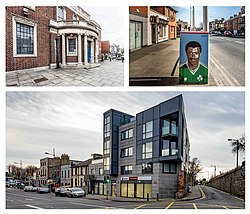

Inchicore (Irish: Inse Chór)[1] is a suburb of Dublin, Ireland. Located approximately 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) west of the city centre, Inchicore was originally a small village separate from Dublin. The village developed around Richmond Barracks (built 1810) and Inchicore railway works (built 1846), before being incorporated into the expanding city bounds. Inchicore is a largely residential area and is home to the association football club St Patrick's Athletic FC.

History

[edit]Inchicore grew from a small village near a marsh on the River Camac at Inse Chór or Inse Chaoire. Some sources suggest that Inse Chaoire means "sheep island", referring to the spot where sheep were herded and watered outside Dublin city prior to market.[2] Other sources, including the Placenames Database of Ireland, do not give a definitive source for the place name.[1]

In the late 19th century, the village developed into a significant industrial and residential suburb, due primarily to its engineering works and the west city tramway terminus. By the 20th century, Inchicore was incorporated into the administrative area of the expanding city.[2]

The Great Southern and Western Railway, which began constructing its network in 1844, elected to site its workshops in the then countryside at Inchicore outside the built-up suburbs of Dublin. Between the years 1846 and 1848 several houses and a Workmans Dining Hall were built on Inchicore Road. As the works complex expanded in the nineteenth-century house building in Inchicore expanded with the works being the predominant employer.[3]

Inchicore is the location of a large tram yard terminus and coachworks and the major engineering works of the Irish railway network are located here. These are still major employers among other industries and national distribution depots.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]5 kilometres (3.1 mi) west of the city centre, south of the River Liffey, west of Kilmainham, north of Drimnagh and east of Ballyfermot, most of Inchicore is in the Dublin 8 postal district; parts of the area extend into Dublin 10 and Dublin 12.

The townlands of Inchicore North and Inchicore South are located in the civil parish of St. James, in the Barony of Uppercross.

Rivers and streams

[edit]The River Camac enters Inchicore flowing northeast from the Landsdowne Valley in Drimnagh. It flows east through Inchicore, and on through Kilmainham and under Bow Bridge, falling into the River Liffey under Heuston Station. Much of its course is now culverted and covered by buildings.[4] During the eighteenth century small industries, primarily paper and textiles, developed along the Camac, which at the time was characterised by water mills, water wheels and weirs. In the 18th century, mills at Goldenbridge (Glydon Bridge) were producing paper and flour. Much of the industrial archaeology has disappeared but remnants still exist in the area. Kilmainham Mills still exists and much of the machinery is still in place. Although derelict, as of March 2021, work was underway to restore the mill as a visitor attraction.[5]

Other watercourses in the area include the Creosote Stream, which passes through the railworks, and comes to the Liffey at the western end of the Gardens of Remembrance.[6]

Grand Canal

[edit]

The Grand Canal was constructed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It is now a recreational waterway. It passes along the south side of Inchicore. The path along the canal is part of a Slí na Sláinte signposted walking route.[7] There is also an 8.5-kilometre (5.3 mi) long greenway between the 3rd Lock at Inchicore and the 12th Lock at Lucan, which opened in June 2010.[8]

Economy

[edit]Industry

[edit]Inchicore Railway Works is the headquarters for mechanical engineering and rolling stock maintenance for Iarnród Éireann. Established in 1844 by the Great Southern & Western Railway, it is the largest engineering complex of its kind in Ireland with a site area of 295,000 m2 (73 acres).[9] Spa Road Works built trams and buses before its closure in 1977.

Goldenbridge Industrial Estate is a mixed-use area that contains, for example, a number of brewing and gym businesses.[citation needed]

Amenities

[edit]Inchicore's core is at the junction of Emmet Road and Tyrconnell Road. The area is served by a number of small stores including a butcher and deli, a hardware store, ethnic stores, and two mid-size supermarkets. The village centre has several pubs, including the historic Black Lion Inn, and several restaurants and take-aways.[10]

Demographics

[edit]As of the 2016 census, the electoral divisions of Inchicore A and Inchicore B had a combined population of approximately 4,600 people.[11][12]

Religion

[edit]

The Roman Catholic Church operates two parishes in the area, St. Michael's and Mary Immaculate. Both parishes are administered by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, and each has its own church, from which they take the name.

The Oblates Church of Mary Immaculate features a full-size replica of the grotto of Lourdes, which was opened in 1930. The grotto, which is built of reinforced concrete, houses a crib at Christmas time.[citation needed]

St. Jude's Church (Church of Ireland), was an Anglican church built between 1862 and 1864 to serve the community working in the railway works. Only the octagonal spire remains, following the dismantling of the church in 1988.

Governance

[edit]Inchicore is in the jurisdiction of Dublin City Council and for council elections, forms part of the Ballyfermot-Drimnagh Ward. As of the 2024 local elections,[13] the local elected representatives on the City Council were:

- Daithí Doolan (Sinn Féin)

- Vincent Jackson (Non-Party)

- Hazel de Nortúin (People Before Profit)

- Philip Sutcliffe (Independent Ireland)

- Ray Cunningham (Green Party)

Culture

[edit]

There are two community centres, St Michael's and BERA. Arus Mhuire was for many years the location of a popular Sunday night dance for teenagers.[citation needed]

The area used to form part of the parish of St. James, later in a union, and served by St. James' Church, but this church has been deconsecrated, and the attached cemetery is closed and overgrown. In 2010, 7 historic parishes, in three unions, all grouped as the St. Patrick's Cathedral Group, were severed from the cathedral and established as the new Parish of St. Catherine and St. James with St. Audeon, served by St. Audeon's Church, Cornmarket, and St. Catherine and St. James' Church on Donore Avenue.[citation needed]

Arts

[edit]Inchicore has been home to a number of poets. Michael Hartnett, lived on Tyrconnell Road from 1984 until about 1986. A plaque marks the house where he wrote some of Inchicore Haiku near Richmond Park, home to St. Patrick's Athletic Football Club. 'Inchicore Haiku' recounts the hard times in his life after his separation from his family.[citation needed]

Francis Ledwidge, the First World War war poet, has associations with St. Michael's CBS, formerly Richmond Barracks. This is where he enlisted and trained before shipping out to Flanders.[citation needed] The Inchicore Ledwidge Society runs events to raise awareness of Ledwidge's life and works, and holds an annual wreath-laying ceremony in the Irish National War Memorial Gardens.[14]

Another Irish poet, Thomas Kinsella (1928–2021), was born and lived on Phoenix Street in Inchicore as a child. He attended the local Model School.[15]

The tramp writer Jim Phelan (1895–1966) was born in Inchicore. On completing 15 years in prison for his part in the murder of a post mistress's son in a robbery in Liverpool in 1923, Phelan roamed the byways of England and wrote several books about his prison experience.[citation needed] The artist Sean Scully (b. 1945) was also born in Inchicore and moved to London When he was four years old.[16]

The courts-martial of a number of figures in the 1916 Rebellion, including poet Patrick Pearse, took place in Richmond Barracks. A number of surviving buildings of the barracks have been restored, with the former gymnasium redeveloped ahead of the 1916 centenary celebrations. It contains wall panels and a tapestry that highlight the people court martialled there.[17]

Parks

[edit]

The parks in the area include Grattan Crescent Park and Jim Mitchell Park, which hold playgrounds, as well as Turvey Park, and the park grounds adjoining the Mary Immaculate Catholic Church. To the south, there is Lansdowne Valley Park.

The Irish National War Memorial Gardens, containing a monument designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, lies just to the north of Inchicore; there is an Inchicore entrance on Con Colbert Road. It commemorates the fallen Irish of the Great War. Official record books held in museum buildings there are inscribed with the names of those who gave their lives. The gardens are also accessible from the South Circular Road, en route toward Phoenix Park, which can be accessed by crossing over Islandbridge (Sarah Bridge).

Museums

[edit]There is a museum at Richmond Barracks, which reopened in May 2016 as part of the centenary celebrations of the Easter Rising. Prisoners were taken to Richmond Barracks for processing after the surrender of the insurgents in 1916. Nearby Kilmainham Jail, now a national museum, was the scene of the execution of leaders of Easter Rising of 1916. The Irish Museum of Modern Art, housed in the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, is also nearby.

Goldenbridge Cemetery, accessible via guided tours from the nearby Richmond Barracks, was the first dedicated Catholic cemetery in Ireland that opened after Catholic Emancipation. It opened in 1828, shortly before the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829. Goldenbridge is the burial place of modern Ireland's first head of government, President of the Executive Council W. T. Cosgrave, who died in 1965.[citation needed]

Education

[edit]Primary schools in the area include Gaelscoil Inse Chor,[18] Scoil Mhuire Gan Smál (Oblates) NS,[19] Our Lady of Lourdes NS,[20] and Inchicore National School.[21] The restored 'Model School' (Inchicore NS) was built in 1853 as a prototype facility for government funded non-denominational primary school education in Ireland.[22]

Secondary schools serving the area include Mercy Secondary School.[23] This co-educational Catholic school,[24] under the trusteeship of CEIST, is located on Thomas Davis Street West, off Emmet Road. It is a member of the Trinity Access Programme (TAP) and the international College For Every Student (CFES) programme. The school has won CFES "School of Distinction" several times.[25]

The Inchicore College of Further Education is located at Emmet Road in Inchicore.

Inchicore Public Library offers club activities (including a film club, book club, knitting club, and poetry club).[citation needed]

Sports

[edit]Soccer

[edit]

St. Patrick's Athletic (founded in 1929 and commonly known as St. Pat's) play in Richmond Park. St. Pat's has played in Inchicore since 1930 (save for time spent exiled due to ground redevelopment). The club has won the League of Ireland Championship on nine occasions. [citation needed]

Former St. Pat's players include Paul McGrath, Ronnie Whelan Snr., Shay Gibbons, Gordon Banks, Curtis Fleming, Paul Osam, Eddie Gormley, Charles Livingstone Mbabazi, Ryan Guy, Keith Fahey, Kevin Doyle, Christy Fagan, Chris Forrester and Ian Bermingham. St Patrick's Athletic host a number junior and intermediate sides at Inchicore, including Lansdowne Rangers, Inchicore Athletic and West Park Albion.[citation needed]

Gaelic games

[edit]The 1889 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship Final between Tipperary and Laois was played at what is now the Inchicore Sports and Social Club.

Liffey Gaels GAA club was founded in 1951. It was known as Rialto Gaels for over twenty years. In the 1970s, it changed its name to SS. Michael and James's to reflect the efforts of the teachers and students of these schools in the development of the club. In 1984, a local juvenile club, Donore Iosagain, amalgamated with SS. Michael and James's and the club was renamed the Liffey Gaels. The club plays home games at East Timor Park on Sarsfield Road in Inchicore.[26]

Other sports

[edit]Men's, women's, boys and girls basketball teams are based in Oblate Hall.[27]

Indoor climbing and bouldering centre "Gravity" based in Goldenbridge Industrial Estate.[28]

Teams taking part in Dublin Roller Derby league train and teach skating in Inchicore Community Sports Centre.

Infrastructure

[edit]Inchicore is accessed by multiple roads and served by a range of Dublin Bus services. Although the site of Ireland's main railway service yards, it has no mainline rail service, but it is served by the Luas tramway system, which runs along its filled-in permanent way, and serves the area from Blackhorse to Suir Bridge.

Inchicore is passed on its southern edge by the Grand Canal, developed by economic progressives of the day and that was, at its peak, the major passenger and commercial trading route through central Ireland, running through the productive farmlands and peat bogs of the Irish midlands. Originally carrying significant traffic during the eighteenth century, it is now a recreational waterway.[29]

| Preceding station | Luas | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luas Red Line stops serving Inchicore | ||||

| Rialto towards The Point or Connolly | Suir Road | Bluebell towards Tallaght or Saggart | ||

| Goldenbridge | ||||

| Drimnagh | ||||

| Blackhorse | ||||

Notable people

[edit]- John Aspinall, first-class cricketer.[citation needed]

- Joe Carr Irish amateur golfer who was inducted to the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2007.[citation needed]

- Timothy Coughlin, one of the trio of Republican dissidents who assassinated Kevin O'Higgins, Minister of Justice of the Irish Free State in 1927, lived in Inchicore.[citation needed]

- Stephen Gillmurphy, independent video game developer[citation needed]

- Michael Hartnett stayed in Inchicore when he wrote 'Inchicore haiku' (1984), a plaque marks his former home on Emmet Road.[citation needed]

- Peadar Kearney, lived at 25 O'Donoghue Street, writer of the Irish national anthem.[citation needed]

- Thomas Kinsella, one of Ireland's best-known modern poets, was born and raised in Inchicore.[15]

- Michael Mallin, 1913 strike leader, was later executed for his part in the 1916 Rising. A plaque marks his home at 122-122A Emmet Road.[30]

- Kathleen Mills was born and lived in Inchicore. A plaque marks her former home at 1 Abercorn Terrace. [citation needed]

- Jim Mitchell was born and raised in Inchicore. He was a politician who served in the cabinets of Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald (1981–82; 1982–87).[citation needed]

- Anne O'Brien, Irish association football (soccer) player.[citation needed]

- Constantine Scollen, the Oblate missionary priest, began his career here as a teaching brother prior to going to Canada. [citation needed]

- Sean Scully, artist, lived in Inchicore as a small child.[31]

- Tom Scully, priest and Gaelic football figure, was based in Inchicore in later life.[32]

- Kathryn Thomas, television presenter, lives in Inchicore.[33]

- Richie Towell, professional footballer for Celtic, Hibernian, Dundalk and Brighton & Hove Albion grew up and lived in Inchicore for most of his life.

- Members of the band The Wolfe Tones were born in Inchicore and lived on Tyrconnell Road.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Inchicore / Inchicore". logainm.ie (in Irish). Placenames Database of Ireland. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

Ní fios go cinnte céard atá sa dara heilimint

- ^ a b "Your guide to Inchicore: Railway village tucked between the river and the canal". thejournal.ie. Journal Media Ltd. 10 August 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Geraghty, Hugh; Rigney, Peter (1983). "The Engineers' Strike in Inchicore Railway Works, 1902". Saothar. 9: 20–31. JSTOR 23193861.

- ^ Doyle, Joseph W. (2012) [2008]. Ten Dozen Waters: The Rivers and Streams of County Dublin (6th ed.). Dublin, Ireland: Rath Eanna Research. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-9566363-5-5.

- ^ McQuillan, Deirdre. "Kilmainham Mills restoration: A 'game changer' for Dublin 8". The Irish Times. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Doyle, Joseph W. (2012) [2008]. Ten Dozen Waters: The Rivers and Streams of County Dublin (6th ed.). Dublin, Ireland: Rath Eanna Research. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-9566363-5-5.

- ^ "Irish Heart Sli na Slainte route map". Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Opening of the Grand Canal Way Green Route 3rd Lock to 12th Lock – 18th June 2010". South Dublin County Council. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ "Inchicore Railway Works, Dublin 8, Dublin City". Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Nolan, Jack (1 December 2019). "Report on Scoping Exercise Inchicore - Kilmainham"Building a Sustainable Community"" (PDF). Report Commissioned by Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government on Behalf of Minister of State Damien English TD: 17. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Dublin By Numbers - Inchicore". dublinlive.ie. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Ireland: Dublin - Electoral Divisions". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Local Elections 2024 Results" (PDF). Dublin City Council. 7 June 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Society honours late poet Ledwidge". Drogheda Independent. 8 August 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Obituary: Thomas Kinsella, the gifted poet who lived and breathed Dublin". Irish Independent. 26 December 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/sean-scully-world-famous-irish-artist-and-son-of-inchicore/38674606.html

- ^ "Richmond Barracks". dmwcreative.ie. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ gov.ie - Roll number 19589U school detail

- ^ gov.ie - Roll number 17083B school detail

- ^ gov.ie - Roll number 07546J school detail

- ^ gov.ie - Roll number 20139T school detail

- ^ Cullinan, Emma. "School among the trees is a triumph". The Irish Times.

- ^ "Mercy Secondary School". mercyinchicore.ie.

- ^ gov.ie - Roll number 60872A school detail

- ^ "33 Schools Recognized as Exemplary Across the United States & Ireland". CFES Brilliant Pathways. 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Liffey Gaels Information". inchicore.info. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020.

- ^ "Oblate Basketball Club".

- ^ "Gravity Climbing Centre".

- ^ Kelly, Olivia. "Study proposes range of schemes to protect and improve canals". The Irish Times. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Whelan, Zuzia. "In Inchicore, Some Think Emmet Hall Should Be a Protected Structure". Dublin Inquirer. No. 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Artist Seán Scully honoured in Inchicore". rte.ie. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

Scully was born in [Inchicore] Dublin in 1945, four years later his family moved to London

- ^ Nolan, Pat (9 April 2020). "A tribute to legendary former Offaly football manager Father Tom Scully". Irish Mirror. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Dwyer, Liz (24 May 2018). "Kathryn Thomas presents a new crib for baby". The Irish Times. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

External links

[edit]- History of Inchicore from inchicore.info (archived 2020)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch