Joseph Desha

Joseph Desha | |

|---|---|

| |

| 9th Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office August 24, 1824 – August 26, 1828 | |

| Lieutenant | Robert B. McAfee |

| Preceded by | John Adair |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Metcalfe |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky | |

| In office March 4, 1807 – March 3, 1819 | |

| Preceded by | George M. Bedinger |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Metcalfe |

| Constituency | 6th district (1807–1813) 4th district (1813–1819) |

| Member of the Kentucky Senate | |

| In office 1802–1807 | |

| Member of the Kentucky House of Representatives | |

| In office 1797–1798 | |

| In office 1799–1802 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 9, 1768 Monroe County, Pennsylvania, British America |

| Died | October 11, 1842 (aged 73) Georgetown, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | Margaret Bledsoe |

| Children | 13, including Isaac B. Desha |

| Relatives | Robert Desha (brother) |

| Profession |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | Kentucky militia |

| Years of service | 1793–1794 1813 |

| Rank | Major general |

| Battles/wars | |

Joseph Desha (December 9, 1768 – October 11, 1842) was a U.S. Representative and the ninth governor of the U.S. state of Kentucky. After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Desha's Huguenot ancestors fled from France to Pennsylvania, where Desha was born. Eventually, Desha's family settled near present-day Gallatin, Tennessee, where they were involved in many skirmishes with the Indians. Two of Desha's brothers were killed in these encounters, motivating him to volunteer for "Mad" Anthony Wayne's campaign against the Indians during the Northwest Indian War. Having by then resettled in Mason County, Kentucky, Desha parlayed his military record into several terms in the state legislature.

In 1807, Desha was elected to the first of six consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. A Democratic-Republican, he was considered a war hawk, supporting the War of 1812. In 1813, he volunteered to serve in the war and commanded a division at the Battle of the Thames. Returning to Congress after the war, he was the only member of the Kentucky congressional delegation to oppose the unpopular Compensation Act of 1816. Nearly every other member of the delegation was defeated for reelection after the vote, but Desha's opposition to the act helped him retain his seat. He did not seek reelection in 1818, and made an unsuccessful run for governor in 1820, losing to John Adair. By 1824, the Panic of 1819 had ruined Kentucky's economy, and Desha made a second campaign for the governorship almost exclusively on promises of relief for the state's large debtor class. He was elected by a large majority, and debt relief partisans captured both houses of the General Assembly. After the Kentucky Court of Appeals overturned debt relief laws favored by Desha and the majority of the legislature, the legislators abolished the court and created a replacement court, to which Desha appointed several debt relief partisans. The existing court refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the move, and during a period known as the Old Court – New Court controversy, two courts of last resort existed in the state.

Although popular when elected, Desha's reputation was damaged by two controversies during his term. The first was his role in the ouster of Horace Holley as president of Transylvania University. While the religious conservatives on the university's board opposed Holley because they considered him too liberal, Desha's opposition was primarily based on Holley's friendship with Henry Clay, one of Desha's political enemies. After Desha bitterly denounced Holley in an address to the legislature in late 1825, Holley resigned. Desha's reputation took a further hit after his son, Isaac B. Desha, was charged with murder. Partially because of Desha's influence as governor, two guilty verdicts were overturned. After the younger Desha unsuccessfully attempted suicide while awaiting a third trial, Governor Desha issued a pardon for his son. These controversies, along with an improving economy, propelled Desha's political foes to victory in the legislative elections of 1825 and 1826. They abolished the so-called "Desha court" over Desha's veto, ending the court controversy. In a final act of defiance, Desha threatened to refuse to vacate the governor's mansion, although he ultimately acquiesced without incident, ceding the governorship to his successor, National Republican Thomas Metcalfe. At the expiration of his term, he retired from public life and ultimately died at his son's home in Georgetown, Kentucky, on October 11, 1842.

Early life and career

[edit]Joseph Desha was born to Robert and Eleanor (Wheeler) Desha in Monroe County, Pennsylvania, on December 9, 1768.[1] He was of part French Huguenot ancestry, and his ancestors had fled from France to Pennsylvania after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which had largely protected the Huguenots from religious persecution.[2] He obtained a limited education in the state's rural schools.[3] In July 1781, Desha's family relocated to Fayette County, Kentucky, and the following year, they settled in what was then known as Cumberland district near the present-day city of Gallatin, Tennessee.[4] Desha's younger brother, Robert, would later represent Tennessee in the U.S. House of Representatives.[5]

Like most frontier settlers, the Desha family frequently found themselves in conflict with American Indians after moving to Tennessee, and between the ages of 15 and 22, Joseph Desha volunteered in several military campaigns against them.[6] In one such campaign, two of his brothers were killed while fighting alongside him.[7] Following the war, Desha lived with William Whitley in the town of Crab Orchard, Kentucky.[8] He married Margaret "Peggy" Bledsoe in December 1789.[4] The couple had thirteen children over the course of their marriage.[9] In 1792, the family moved to Mason County, Kentucky, where Desha worked as a farmer.[1] In 1794, he served in the Northwest Indian War under Lieutenant William Henry Harrison.[10] He participated in General "Mad" Anthony Wayne's rout of the Indians at the August 20 Battle of Fallen Timbers.[11]

Desha entered politics in 1797, when he was elected as a Democratic-Republican to the Kentucky House of Representatives.[3] When the House debated the Kentucky Resolutions in 1798, he chaired the Committee of the Whole.[12] He again served in the House from 1799 to 1802, and was elected to the Kentucky Senate from 1802 to 1807.[1] Concurrent with his legislative career, he continued to serve in the state militia. On January 23, 1798, he was appointed as a major in the 29th Regiment.[13] He was promoted to colonel on March 23, 1799, and on September 5, 1805, he was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the 7th Brigade of the Kentucky Militia.[13] On December 24, 1806, he was made a major general, remaining with the 7th Brigade.[13] He owned slaves.[14]

Service in the House and the War of 1812

[edit]Desha was elected without opposition to the first of six consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1807.[15] Though he was known as a capable orator, he did not speak often, claiming it was best "to think much and speak but little."[9] He opposed renewing the charter of the First Bank of the United States because most of the bank's investors were foreigners.[16] Specifically, he was concerned about the fact King George III of Great Britain was a major shareholder.[16] (It was thought by many that the British monarch was on the verge of madness at this time.)[16] The bank's charter ultimately was not renewed in 1811.[17]

Early in his career, Desha advocated an adequate army to defend American territory from Great Britain and France.[9] He supported President Thomas Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 and related enforcement legislation.[18] He was considered a war hawk, and House Speaker Henry Clay, a fellow Kentuckian and leader of the War Hawks in the House, selected him to serve on the House Foreign Relations Committee during the Twelfth Congress (1811–13).[18] Consistent with Clay's expectations, Desha consistently supported the war measures brought before the House, including bills to arm merchant ships, increase the number of regular troops in U.S. Army, and authorize President James Madison to accept volunteer units for military service.[18] Proclaiming his dissatisfaction with Macon's Bill Number 1, he maintained that all embargoes and sanctions would fail as long as "the British have a Canada or a Nova Scotia on the continent of America", although he acknowledged the high cost in both money and lives that annexation of Canada would entail.[19] On June 4, 1812, he voted in favor of a declaration of war on Great Britain, officially beginning the War of 1812.[18]

Desha returned to Kentucky after the congressional session.[18] He responded to Governor Isaac Shelby's call for volunteers to serve in William Henry Harrison's campaign into Upper Canada.[18] He was commissioned a major general and given command of the 2nd Division of Kentucky militia.[18] The 3,500-man division, composed of the 2nd and 5th Brigades and the 11th Regiment, assembled on the Ohio River at Newport, Kentucky.[18] They joined Harrison in forcing the British retreat from Detroit and held the Indian allies of the British off his left flank during the American victory at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813.[18] According to historian Bennett H. Young, Desha's old friend William Whitley had a premonition of his own death the night before the battle and gave his rifle and powderhorn to Desha, asking him to convey it to his widow, along with a message of his affection.[8] Whitley was indeed killed in the fighting the following day.[8]

Desha resumed his service in Congress at its next term.[18] He was disappointed at the decision not to pursue the annexation of Upper Canada and to ignore British impressment of American mariners in favor of pursuing peace with the British.[18] Ultimately, he was dissatisfied with the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war.[18] When William Henry Harrison was being considered by Congress for the position of general-in-chief in late 1813 and early 1814, Desha opposed giving him the title because he claimed that Harrison had determined not to pursue British General Henry Procter following the Battle of the Thames and had only done so after strenuous urging by Isaac Shelby.[20] Desha's charge was a contributing factor in Congress's decision to remove Harrison's name from a resolution of thanks for service in the Northwest Army and withhold from him a Congressional Gold Medal.[20] Both Harrison and Shelby denied Desha's account, and as the issue began to damage Desha's reelection chances, he partially recanted his story.[21] He claimed that he had only told some friends that Harrison was wary of pursuit during a council of war held at Sandwich, Ontario, after the battle, but that he had not personally witnessed a disagreement over the pursuit between Harrison and Shelby.[20]

Desha gradually became more conservative after his return to the House, consistently resisting expansion of the U.S. Navy.[22] He also opposed Secretary of War James Monroe's request to maintain a standing peacetime army of 20,000 men.[23] Desha argued that a large standing army provided the advocates of a larger federal government with an excuse to increase taxes, and proposed that the standing army should consist of only 6,000 men.[23] A coalition of Federalists and conservative Democratic-Republicans in the House united to adopt Desha's suggestion by a vote of 75–65.[24] The version of the bill passed by the Senate, however, required a standing army of 15,000 men.[24] The legislation was referred to a conference committee, which ultimately adopted a compromise of 10,000 men.[24]

During the Fourteenth Congress (1815–17), he was the only member of the twelve-member Kentucky congressional delegation to oppose the Compensation Act of 1816.[25] The act, sponsored by fellow Kentuckian Richard Mentor Johnson, modified congressional compensation, paying each member a flat salary of $1,500 a year instead of a $6 per diem while Congress was in session.[25] The measure proved extremely unpopular with the electorate.[25] Every member of the Kentucky delegation that voted for the bill – excepting Johnson and Henry Clay, who were both extremely popular – lost his congressional seat, either because he did not seek reelection or because he was defeated by another candidate.[26]

Desha served as chairman of the Committee on Public Expenditures during the Fifteenth Congress (1817–19).[5] On March 14, 1818, he voted with the minority against a resolution introduced by South Carolina's William Lowndes asserting Congress's power to appropriate federal funds for the construction of internal improvements.[27] He did not run for reelection in 1818.[5]

Gubernatorial election of 1820

[edit]

Desha was one of four candidates who sought the governorship of Kentucky in 1820.[1] In the aftermath of the Panic of 1819 – the first major financial crisis in United States history – the primary issue of the campaign was debt relief.[28] Sitting governor Gabriel Slaughter had lobbied for some measures favored by the state's large debtor class, particularly punitive taxes against the branches of the Second Bank of the United States in Louisville and Lexington.[29] The Second Party System had not yet developed, but there were nonetheless two opposing factions that arose around the debt relief issue.[15] The first – primarily composed of land speculators who had bought large land parcels on credit and were unable to repay their debts due to the financial crisis – was dubbed the Relief Party or faction and favored more legislation favorable to debtors.[29] Opposed to them was the Anti-Relief Party or faction; it was composed primarily of the state's aristocracy, many of whom were creditors to the land speculators and demanded that their contracts be adhered to without interference from the government.[28] They claimed that no government intervention could effectively aid the debtors and that attempts to do so would only prolong the economic depression.[28]

Although Desha was clearly aligned with the Relief faction, the faction's leader was John Adair, a veteran of the War of 1812 whose popularity was augmented because of his very public defense of the Kentuckians who served under him at the Battle of New Orleans against charges of cowardice by Andrew Jackson.[15][30] Adair won a close election with 20,493 votes, besting William Logan's 19,947 votes, Desha's 12,418 votes, and Anthony Butler's 9,567 votes.[1] Relief partisans also secured control of both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly.[31] Much debt relief legislation was passed during Adair's term, but as his term neared expiration, the Kentucky Court of Appeals struck down one popular and expansive debt relief law as unconstitutional, ensuring that debt relief would again be the central issue in the upcoming gubernatorial election.[32]

Gubernatorial election of 1824

[edit]With Adair constitutionally ineligible to seek a second consecutive term, Desha was the first candidate to publicly declare his intention to seek the governorship in 1824.[15] He began his campaign in late 1823 and faced little opposition until Christopher Tompkins declared his candidacy in May 1824.[33] Tompkins was a little-known judge from Bourbon County who vehemently held to the principles of the Anti-Relief faction.[34] Colonel William Russell, a military veteran of 50 years, also sought to carry the mantle of the Anti-Relief faction.[35] While not as eloquent or well-versed in the faction's rhetoric, he had few political enemies and his military career brought him great respect among the electorate.[35]

While Tompkins and his supporters primarily campaigned through the state's newspapers, most of which supported the Anti-Relief faction, Desha traveled the state making stump speeches.[34] Offering no specific platform, he focused exclusively on the idea that he opposed "judicial usurpation" and believed "all power belonged to the people".[36] He was generally acknowledged as the candidate of the Relief Party, but historian Arndt M. Stickles has noted that he used Anti-Relief rhetoric in some counties.[37] Desha attacked Tompkins' record as a judge, claiming that he had consistently supported the Second Bank of the United States and the current Court of Appeals.[36] This, Desha said, put him in direct and open opposition to the state's farmers and ensured that, if he were elected, the state would be governed by the judicial branch, not the governor.[36] Desha claimed the state's newspapers persecuted him the same way the Anti-Relief party persecuted debtors.[38] He also charged that Tompkins was not the true choice of the Anti-Relief party, but only gained its support by being the first candidate with that position to announce his candidacy.[36] Backers of Russell, who consistently ran a distant third in voter support, agreed with this claim, saying Tompkins had joined the race before a date that had been previously agreed on among Anti-Relief candidates, giving him an unfair advantage over Russell.[39]

Anti-Relief partisans opened many lines of attack against Desha. They said his refusal to articulate a specific campaign platform showed that he was trying to be all things to all people.[36] They assailed his military record, claiming he had only volunteered for service in the War of 1812 after being promised command of a division, that he balked at fighting and discouraged General Harrison's pursuit of the British and Indians, and that he billed excessive expenses to the government after his service.[40] Desha's legislative career was also subject to scrutiny and attack.[41] Anti-Relief partisans claimed that he had espoused certain positions for the sole purpose of pitting the state's agrarian interests against its aristocracy.[41] They charged that he had secretly favored the Compensation Act of 1816 and had worked to pass it, despite his vote against it.[41] In contrast to his rhetoric in favor of a strong, well-equipped army and navy, opponents claimed he had actually voted against increasing the military's budget.[41] As further evidence of his lack of trustworthiness, they pointed to his vote for William H. Crawford while serving as a presidential elector in 1816, even though Kentuckians were nearly unanimous in their support of James Monroe.[41]

Although Desha was universally acknowledged as the leading candidate during the early months of the campaign, as election day approached, some began to doubt whether he could withstand the withering attacks of the Anti-Relief Party.[39] The Frankfort Argus, a pro-Desha newspaper, remained confident, however, predicting that the Relief candidate would win by a margin of 4-to-1.[39] On election day, Desha secured a comfortable victory, receiving 38,378 votes, nearly 60% of the votes cast, and carrying large majorities even in some strongly Anti-Relief counties.[37] Tompkins garnered 22,499 votes, with his support concentrated mostly in Central Kentucky.[1][39] Russell finished third with 3,900 votes.[1] Desha and his allies in the General Assembly interpreted the victory as a mandate from the voters to aggressively pursue their debt relief agenda.[9]

Governor of Kentucky

[edit]

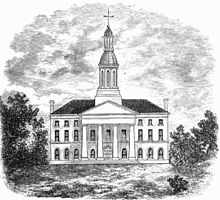

On November 4, 1824, just months after the election, the state capitol building was destroyed by a fire.[42] Some furnishings and records were saved, but the four-year-old building was a total loss.[42] When Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette toured the United States in 1825, a new capitol had not yet been constructed and the governor's mansion was too small to host a proper reception, so the governor had to entertain the dignitary at Weisiger's Tavern.[43]

Desha's major accomplishment as governor was in the area of internal improvements.[44] In 1825, he convinced the legislature to fund the creation of the Louisville and Portland Canal on the Falls of the Ohio.[44] The canal opened in 1830, and proved very profitable, so much so that Desha lamented the fact that the state had split the cost of the project – and consequently, its profits – with the federal government and private investors.[44] He also urged state investment in a turnpike joining Maysville to Louisville via Lexington. He advocated using excess money earmarked for education to construct hard-surfaced roads in the state, but the General Assembly was less responsive to this suggestion.[45]

Old Court – New Court controversy

[edit]Kentucky historian Thomas D. Clark wrote that Desha "made rash promises to relieve the horde of bankrupt voters ... promises on which he had to deliver."[46] His first address to the legislature was critical of the judiciary in general, especially the Supreme Court's recent decision in the case of Green v. Biddle which held that land claims granted by Virginia in the District of Kentucky prior to Kentucky becoming a separate state took precedence over those later granted by the state of Kentucky if the two were in conflict.[47] Encouraged by Desha's strong stance against the judiciary, Relief partisans set about removing the judges on the Court of Appeals who had earlier struck down their debt relief legislation.[30] The first punitive measure proposed against the offending judges was to reduce their salaries to 25 cents per year, but this course was quickly abandoned.[30] Next, legislators attempted to remove the judges by address, but they found they lacked the necessary two-thirds majority in both houses to effect this removal.[48]

Finally, on December 9, 1824, the Kentucky Senate passed a measure repealing the legislation that created the Kentucky Court of Appeals and establishing a new court of last resort in the state.[49] The bill was sent to the House, and a vigorous debate ensued on December 23.[50] During the debate, which continued past midnight, Desha appeared on the floor of the chamber to lobby legislators to support the bill and actually moved the previous question to end debate, which was, in the words of Kentucky historian Lowell H. Harrison, a "flagrant violation of House rules".[50][51][52] The House passed the bill by a vote of 54–43, and Desha signed it immediately.[51]

On January 10, 1825, Desha appointed four justices to the new court.[53] He chose his Secretary of State, former U.S. Senator William T. Barry, as chief justice.[53] The other three members were Lexington lawyer James Haggin, Circuit Judge John Trimble (brother of Supreme Court Justice Robert Trimble), and Benjamin Patton.[54] Of the new court – called by detractors the "Desha court" – Barry "seems to have been the only one who had in a measure an even show in experience, prestige, and ability to rank as a jurist with the old-court justices", according to Stickles.[55] Achilles Sneed, clerk of the Old Court, refused to surrender the court's records to Francis P. Blair, clerk of the New Court, so Blair took the records from Sneed's office by force, and Sneed was fined 10 pounds for contempt of court because of his refusal to cooperate.[50] The Old Court continued to hear cases in a Frankfort church, while the New Court occupied the official court chambers.[50] Neither recognized the other, and both claimed to be the legitimate court of last resort in the state.[50] Most of the state's lawyers and judges were supporters of the Old Court and continued to practice before them and abide by their mandates, but others chose to acknowledge the New Court as legitimate.[56]

Although Desha and his entire administration campaigned on behalf of New Court candidates during the legislative elections of 1825, Old Court supporters regained the state House and evenly split the Senate between Old and New Court supporters.[50][57] Desha's message to the newly reconstituted General Assembly remained critical of banks and the judiciary, but urged legislators to seek a compromise to resolve the court question.[58] Stickles records that Desha was sincere in his desire for a compromise, albeit one that would save face for the New Court Party.[59] He promised that, if the legislature would again authorize appointment of a new set of judges, he would appoint them equally from both parties.[60] Another plan would have expanded the court to six judges, with three appointed from each party.[61] One legislator proposed that all members of both courts resign, along with Desha, lieutenant governor Robert B. McAfee, and all the legislators in the General Assembly, essentially allowing the state government to reset itself.[50] This bill passed the House but was killed in the Senate.[50] The House passed a measure to restore the Old Court, but the Senate deadlocked on the measure and McAfee, the presiding officer in the Senate, cast the tie-breaking vote to defeat it.[50]

By 1826, the economic climate in the state had improved significantly.[50] Seeing the resultant upsurge in Old Court support, two of the four New Court justices resigned.[62] Desha offered the appointments to three different individuals, all of whom ignored or rejected them.[62] John Telemachus Johnson finally accepted the appointment in April 1826, and the New Court met with only three justices during its 1826 term.[62] In the August 1826 elections, the Old Court Party won majorities of 56–44 in the House and 22–16 in the Senate.[63] Desha again encouraged the legislators to compromise to resolve the court impasse.[63] The Old Court majorities in both houses, however, completely repudiated the New Court, passing a bill to restore the Old Court and overturn all legislation related to the New Court.[50] Desha vetoed the bill, and scolded the legislators for passing a blatantly partisan bill as opposed to a compromise measure.[64] The General Assembly overrode Desha's veto on January 1, 1827.[50] In a conciliatory move, the Senate confirmed Desha's appointment of George M. Bibb, a New Court partisan, to a position on the re-empowered Old Court after John Boyle resigned to accept a federal judgeship in November 1826.[65]

Pardon of Isaac Desha

[edit]

Governor Desha's reputation was further tarnished because of a pardon issued to his son. On November 2, 1824, Isaac B. Desha had brutally murdered Francis Baker, a Mississippian who was visiting Kentucky. On November 24, 1824, John Rowan, one of the governor's allies in the General Assembly, introduced legislation ordering the Fleming County Circuit Court to convene a special session on January 17, 1825, for Isaac Desha's trial and providing that the accused should have the option to request a change of venue to Harrison County at that time.[66][67] Miles from the scene of the murder, Harrison County was the governor's home county, and he possessed a great deal of influence with officials there.[42] Governor Desha appeared before the legislative committee considering the bill on November 26 and asked that they report it favorably to the full legislature.[66] This was done, and the bill was approved on December 4, 1824.[66]

At his trial in December, Isaac Desha requested the change of venue; the case was transferred to Harrison County and scheduled for early January.[66] John Trimble was scheduled to hear the case, but Governor Desha appointed him to the New Court of Appeals following the "abolishment" of the Old Court in late 1824.[68] Trimble personally appealed to Judge George Shannon of Lexington to hear the case.[69] Governor Desha assembled a formidable defense team for his son, including his newly appointed Secretary of State, William T. Barry; John Rowan, who had just been elected to the U.S. Senate; and former congressmen William Brown and T. P. Taul.[70] William K. Wall and future Congressman John Chambers – the Commonwealth's Attorneys for Harrison and Fleming counties, respectively – collaborated with attorney Martin P. Marshall to prosecute the case.[70] Governor Desha attended each day of the proceedings, seated with the defense counsel.[71]

Despite the best efforts of his father to secure a favorable venue, judge, and defense team, on January 31, 1825, the jury convicted Isaac Desha of murder and sentenced him to hang.[42][72] Rowan immediately requested a new trial upon grounds of jury interference, and Shannon granted the request on February 10.[69] Jury selection proved problematic, occupying at least parts of four terms of the Harrison County Circuit Court.[73] In September 1825, a jury was finally empaneled.[73] The judge, Harry O. Brown, had been temporarily appointed to his position by Governor Desha to fill a vacancy.[74][75] Desha was again found guilty, and sentenced to hang on July 14, 1826.[76] Judge Brown overturned the verdict because the prosecution had not proven that the murder took place in Fleming County, as alleged in the indictment against Desha.[74][75] The state argued that this was of no consequence, since a change of venue had already been granted, but the judge's ruling stood, and Governor Desha's reputation took a further hit.[74]

In July 1826, Isaac Desha, free on bail while awaiting a third trial and apparently in a highly intoxicated state, attempted suicide by cutting his own throat.[74][75] Physicians saved his life by reconnecting his severed windpipe with a silver tube.[74] He recovered, and in June 1827, faced a third trial.[75] During the June term of the court, Desha's lawyers used a number of peremptory challenges to again prevent the court from empaneling a jury.[74] The judge ordered him held without bail until the next session of the court, but Governor Desha, who was present at the proceedings, stood and issued a pardon for his son, as well as lambasting the judge in a lengthy impromptu speech.[74] Some accounts hold that the governor immediately resigned upon granting the pardon, but the official records reflect no such action.[76]

Following his release, Isaac Desha traveled to Texas under an alias, where he robbed and killed another man.[74] He was identified based on family resemblance and the silver pipe that had earlier saved his life.[74] After being arrested, he confessed to both murders.[74] He died of a fever the day before his trial in August 1828.[77]

Conflict with Horace Holley

[edit]

Another controversial issue during Desha's tenure was his disdain for Horace Holley, president of Transylvania University. From the time Holley assumed the post of president in 1818, the university had risen to national prominence and attracted well-qualified and well-respected faculty members such as Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, Daniel Drake, Charles Caldwell, William T. Barry, and Jesse Bledsoe.[78] However, Holley's New England Unitarian beliefs were too liberal for the tastes of many in Kentucky.[1] Many called Holley an infidel and charged that he was a drinker and a gambler.[79] He was criticized for spending time at the horse races and for furnishing his home with nude classical statues.[80]

Desha was drawn into the Holley controversy during the 1824 presidential election.[81] When no candidate achieved a majority of the electoral votes cast, the contest was resolved by the U.S. House of Representatives. Desha and the New Court partisans in the General Assembly instructed the state's congressional delegation to cast their votes for Andrew Jackson, but the delegation, led by House Speaker Henry Clay, defied these instructions and voted instead for John Quincy Adams.[81] Because of this vote, Clay, a trustee for Transylvania and supporter of Holley, became Desha's political enemy.[81] Desha's hostility for Transylvania and Holley worsened when, in the aftermath of the Isaac Desha trial, a student at Transylvania delivered a speech critical of the governor in the university's chapel.[42] Although Holley was present for the speech, Transylvania historian John D. Wright Jr. wrote that he did not know the student's topic beforehand and after hearing the speech, made no effort to condone its content.[82] It was Holley's practice, however, to allow students to speak openly about current political matters, regardless of which position they took.[82] Desha maintained that, because Holley had not silenced the student, he was at fault for tacitly condoning disrespectful criticism of the state's chief executive.[83]

Desha vehemently attacked Transylvania and Holley in his annual message to the General Assembly in November 1825.[82] He claimed that the university had not made wise use of the public funding allocated to it by previous Assemblies, noting in particular that Holley's salary as president exceeded his own.[82] Finally, Desha claimed that under Holley, Transylvania had become too elitist and could not be otherwise, given the high cost of attendance.[79][82] Holley, who had traveled to Frankfort to speak with Desha and the legislature, was present for Desha's speech.[84] Afterward, he decided instead to return to Lexington and tender his resignation.[84] Sympathetic members of the university's board of trustees convinced Holley to remain for another year.[85] Kentucky historian James C. Klotter opined that, with Holley's departure, "perhaps the state's best chance for a world-class university had passed."[80]

Gubernatorial legacy and transition

[edit]

The numerous controversies of Desha's term severely damaged his reputation.[86] Harrison recorded that a visitor to Kentucky remarked in 1825, "[Desha] is said by some to possess talents; I have never been furnished with evidence."[86] Harrison further noted that "[b]y 1828, many Kentuckians would have agreed with that assessment."[86]

Desha supported William T. Barry, the Democratic-Republican gubernatorial nominee, to succeed him.[4] Early reports showed Barry leading his opponent, National Republican Thomas Metcalfe, but the final margin favored Metcalfe.[87] Not only did Desha not agree with Metcalfe politically, he believed that the governorship should go to a high-born aristocrat.[4] Although Metcalfe was the son of a Revolutionary War soldier, his nickname of "Old Stone Hammer" indicated his pride in his trade of masonry, which was considered a common profession.[4]

Due to a constitutional quirk, Metcalfe's term was scheduled to begin eight days before the expiration of Desha's.[88] Desha charged that Metcalfe was not allowing him to finish out his term and threatened not to vacate the governor's mansion until his term officially ended.[88] Clark records as legend that, after drinking heavily at a local tavern, Metcalfe and some of his supporters formed a mob and went to the governor's mansion to evict him by force.[88] Accounts in the local newspapers of the time instead record that the Deshas left the mansion peacefully without intervention by Metcalfe.[87]

Later life and death

[edit]At the expiration of his term as governor, Desha retired from public life to his farm in Harrison County.[3] During the final years of his life, Desha and his wife Margaret moved to Georgetown, Kentucky, where one of his sons, a physician, lived. Desha died at his home in Georgetown, Kentucky, on October 11, 1842, and was buried on the grounds.[12] The state erected a monument over his grave.[12] In 1880, both Desha's body and the monument were moved to Georgetown Cemetery.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Harrison, p. 264

- ^ Cisco, p. 170

- ^ a b c "Kentucky Governor Joseph Desha". National Governors Association

- ^ a b c d e Morton, p. 14

- ^ a b c "Desha, Joseph". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- ^ Allen, p. 90

- ^ Allen, p. 91

- ^ a b c Young, p. 119

- ^ a b c d Powell, p. 28

- ^ Tucker, p. 191

- ^ Young, p. 118

- ^ a b c d Young, p. 120

- ^ a b c Trowbridge, "Kentucky's Military Governors"

- ^ "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, 2022-01-13, retrieved 2022-07-07

- ^ a b c d Doutrich, p. 23

- ^ a b c Geisst, p. 16

- ^ Geisst, p. 17

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Heidler and Heidler, p. 152

- ^ White, p. 66

- ^ a b c Quimby, p. 288

- ^ Quimby, pp. 288–289

- ^ Risjord, p. 184

- ^ a b Wills, p. 372

- ^ a b c Risjord, p. 160

- ^ a b c Schoenbachler, p. 35

- ^ Schoenbachler, p. 36

- ^ Risjord, p. 200

- ^ a b c Doutrich, p. 15

- ^ a b Doutrich, p. 14

- ^ a b c Harrison and Klotter, A New History of Kentucky, p. 110

- ^ Doutrich, p. 19

- ^ Doutrich, p. 21

- ^ Doutrich, pp. 24–25

- ^ a b Doutrich, pp. 23–24

- ^ a b Doutrich, p. 24

- ^ a b c d e Doutrich, p. 27

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 43

- ^ Doutrich, p. 26

- ^ a b c d Doutrich, p. 28

- ^ Doutrich, p. 27–28

- ^ a b c d e Doutrich, p. 25

- ^ a b c d e Clark and Lane, p. 22

- ^ Clark and Lane, pp. 23–24

- ^ a b c Johnson and Parrish, p. 18

- ^ Harrison and Klotter, p. 126

- ^ Clark and Lane, p. 21

- ^ Stickles, pp. 44–45

- ^ Bussey, p. 30

- ^ Harrison and Klotter, pp. 110–111

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Harrison and Klotter, p. 111

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 59

- ^ Schoenbachler, p. 106

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 60

- ^ Stickles, p. 61

- ^ Stickles, p. 62

- ^ Allen, p. 88

- ^ Stickles, p. 81

- ^ Stickles, pp. 89, 92

- ^ Stickles, p. 92

- ^ Stickles, pp. 92–93

- ^ Stickles, p. 93

- ^ a b c Stickles, p. 108

- ^ a b Stickles, p. 102

- ^ Stickles, p. 104

- ^ Stickles, pp. 108–109

- ^ a b c d Johnson, p. 38

- ^ Parish, p. 50

- ^ Johnson, pp. 38–39

- ^ a b Johnson, p. 39

- ^ a b Parish, pp. 49–50

- ^ Parish, p. 52

- ^ Parish, p. 60

- ^ a b Parish, p. 61

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Thies, Murder and Inflation

- ^ a b c d Parish, p. 62

- ^ a b Johnson, p. 40

- ^ Muir, p. 321

- ^ Harrison and Klotter, p. 152

- ^ a b Bussey, p. 31

- ^ a b Klotter, "What If..."

- ^ a b c Wright, p. 110

- ^ a b c d e Wright, p. 111

- ^ Clark and Lane, p. 23

- ^ a b Wright, p. 112

- ^ Wright, p. 116

- ^ a b c Harrison and Klotter, p. 112

- ^ a b Morton, p. 15

- ^ a b c Clark and Lane, p. 24

Bibliography

[edit]- Allen, William B. (1872). A history of Kentucky: embracing gleanings, reminiscences, antiquities, natural curiosities, statistics, and biographical sketches of pioneers, soldiers, jurists, lawyers, statesmen, divines, mechanics, farmers, merchants, and other leading men, of all occupations and pursuits. Louisville, Kentucky: Bradley & Gilbert.

- Bussey, Charles J. (2004). "Joseph Desha". In Lowell H. Harrison (ed.). Kentucky's Governors. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2326-7.

- Clark, Thomas D.; Margaret A. Lane (2002). The People's House: Governor's Mansions of Kentucky. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2253-8.

- Cisco, Jay Guy (2009). Historic Sumner County, Tennessee: With Genealogies of the Bledsoe, Cage and Douglass Families and Genealogical Notes of Other Sumner County Families. Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8063-5127-8.

- "Desha, Joseph". Biographical Directory of the United States. United States Congress.

- Doutrich, Paul E. III (January 1982). "A Pivotal Decision: The 1824 Gubernatorial Election in Kentucky". Filson Club History Quarterly. 56 (1).

- Geisst, Charles R. (2004). Wall Street: A History: From Its Beginnings to the Fall of Enron. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517061-0.

- Harrison, Lowell H. (1992). "Desha, Joseph". In Kleber, John E (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- Harrison, Lowell H.; James C. Klotter (1997). A New History of Kentucky. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2008-X.

- Heidler, David Stephen; Jeanne T. Heidler (2004). "Desha, Joseph". Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-362-4.

- Johnson, Leland R.; Charles E. Parrish (1999). Engineering the Kentucky River: The Commonwealth's Waterway (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- Johnson, Lewis Franklin (1916). "The Assassination of Francis Baker by Isaac B. Desha, in 1824". Famous Kentucky Tragedies and Trials: A Collection of Important and Interesting Tragedies and Criminal Trials which Have Taken Place in Kentucky. Louisville, Kentucky: Baldwin Law Book Company, Incorporated.

- Klotter, James C. (April 2005). "What If..." Kentucky Humanities. Kentucky Humanities Council. Archived from the original on January 16, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- "Kentucky Governor Joseph Desha". National Governors Association. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- Morton, Jennie C. (January 1904). "Governor Joseph Desha of Distinguished Huguenot Ancestry". Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society. 2 (4).

- Muir, Andrew Forest (October 1956). "Isaac Desha, Fact and Fancy". Filson Club History Quarterly. 30 (4).

- Parish, John Carl (1909). John Chambers. Iowa City, Iowa: State Historical Society of Iowa. Archived from the original on 2005-03-08.

- Powell, Robert A. (1976). Kentucky Governors. Danville, Kentucky: Bluegrass Printing Company. OCLC 2690774.

- Quimby, Robert S. (1997). The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-585-22081-6.

- Risjord, Norman K. (1965). The Old Republicans: Southern Conservatism in the Age of Jefferson. New York City: Columbia University Press. OCLC 559308071.

- Schoenbachler, Matthew G. (2009). Murder & Madness: The Myth of the Kentucky Tragedy. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2566-4.

- Stickles, Arndt M. (1929). The Critical Court Struggle in Kentucky, 1819–1829. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University.

- Thies, Clifford F. (February 7, 2007). "Murder and Inflation: the Kentucky Tragedy". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- Trowbridge, John M. "Kentucky's Military Governors". Kentucky National Guard History e-Museum. Kentucky National Guard. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- Tucker, Spencer (2012). Encyclopedia of the War Of 1812: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-956-6.

- White, Patrick C. T. (1965). A Nation on Trial: America and the War of 1812. New York City: John Wiley & Sons. OCLC 608865759.

- Wills, Garry (2007). Henry Adams and the Making of America. New York City: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-87266-4.

- Wright, John D. Jr. (2006). Transylvania: Tutor to the West. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9167-X.

- Young, Bennett Henderson (1903). The battle of the Thames, in which Kentuckians defeated the British, French, and Indians, October 5, 1813, with a list of the officers and privates who won the victory. Louisville, Kentucky: J. P. Morton. Archived from the original on March 8, 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

External links

[edit]

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch