KUOM

Radio K - Real College Radio | |

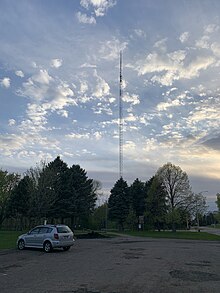

KUOM AM tower with the antenna for 100.7 FM (and KBEM-FM) | |

| |

|---|---|

| Broadcast area | Twin Cities |

| Frequency | 770 kHz |

| Branding | Radio K - Real College Radio |

| Programming | |

| Format | College radio |

| Affiliations | AMPERS |

| Ownership | |

| Owner | |

| History | |

First air date | January 13, 1922 |

Former call signs |

|

Call sign meaning | University of Minnesota |

| Technical information[1] | |

Licensing authority | FCC |

| Facility ID | 69337 |

| Class | D |

| Power | 5,000 watts (daytime) |

Transmitter coordinates | 44°59′54″N 93°11′18″W / 44.99833°N 93.18833°W |

| Translator(s) | See § FM signals |

| Repeater(s) | See § FM signals |

| Links | |

Public license information | |

| Webcast | Listen live |

| Website | radiok |

KUOM (770 AM) – branded Radio K - Real College Radio – is a daytime-only, non-commercial, college radio station licensed to Minneapolis, Minnesota. Owned by the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, the station is operated by students and faculty. It mainly airs alternative rock with other genres of music. The studios are in Rarig Center on the University of Minnesota campus.

KUOM's AM signal operates at 5,000 watts with a non-directional antenna. Its transmitter tower is on the St. Paul - Falcon Heights campus. Due to its low frequency of 770 kHz, combined with the region's excellent soil conductivity,[2] the station's AM coverage is comparable to that of a full-power FM station. Its signal can be heard throughout the Twin Cities area, with grade B coverage as far as St. Cloud and Mankato. However, the AM operation is licensed to broadcast only during daylight hours to avoid interfering with Class A WABC in New York City at night. Therefore, its hours of operation vary from month to month, reflecting local sunrise and sunset times. Sign off, for example, ranges from 4:30 p.m. in winter to 9:00 p.m. in summer. KUOM extends its reach, and adds nighttime service, with two FM translators and one limited-reach FM station that allow KUOM's programming to be heard 24 hours a day. KUOM is also available online.

The university traces its radio activities back more than 100 years, starting with experimental work in 1912, followed by radiotelegraph broadcasts begun in 1920, and radiotelephone broadcasts of market reports inaugurated in February 1921. KUOM's first license as a broadcasting station, originally WLB, was granted on January 13, 1922. This was Minnesota's first broadcasting station, making KUOM one of the oldest surviving radio stations in North America.

Programming

[edit]Programs include a wide variety of Independent and Alternative music, and feature specialty shows dedicated to Metal, Hip Hop, Jazz, R&B, Electronic, Punk, Folk, and World Music. The station specializes in promoting local musicians and produces local shows, including the award-winning Off The Record.[3][4] Music submissions are filtered through a large group of volunteer reviewers and DJs.

A news program called Access Minnesota began in 2004. It is carried on several dozen radio stations across the state.[5] Focusing on politics and the media, the program is produced by Radio K and the Minnesota Broadcasters Association.[6]

History

[edit]WX2 and 9XI

[edit]Originally called "wireless telegraphy," radio experimentation at the University of Minnesota began in 1912, conducted by Professor Franklin Springer, using spark transmitters that could only send the dots-and-dashes of Morse code.[7] In January 1916, it was reported that as a "first in the northwest," the College of Engineering was planning to transmit the progress of that night's basketball game between the University of Minnesota and the visiting University of Iowa team.[8]

In late 1919, following the end of World War I, the university was authorized to establish a "War Department Training and Rehabilitation School" station, with the call sign WX2.[9] This was followed in early 1920 by the issuance of an experimental radio license, with the call sign 9XI.[10][11] These operations were under the oversight of electrical engineering professor C. M. Jansky Jr., the older brother of Karl Jansky.[12]

In 1920 a one-kilowatt spark transmitter was installed. In addition to communicating with amateur and other university stations, 9XI, in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, transmitted market and weather reports by radiotelegraph.[13] The development of vacuum tube transmitters, capable of audio transmissions, would lead to further advances, and over time 9XI began including broadcasts for general audiences. On February 2, 1921, the station inaugurated audio transmissions, as part of its nightly 8:30 p.m. broadcasts of market reports.[14] In the fall of 1921, the station gave "a running account of a Minnesota football game through notes brought to the station's studios by a relay of students from the sidelines at the field."[15] December saw the beginning of a daily noon broadcast of livestock prices.[16] These transmissions initially originated from the electrical engineering building on the Minneapolis campus, where a transmitter was installed on the roof.

WLB

[edit]Initially there were no formal standards for radio stations making broadcasts intended for the general public. However, effective December 1, 1921, the United States Department of Commerce, which supervised radio at this time, issued a regulation requiring that stations making broadcasts intended for the general public now had to operate under a "Limited Commercial" license."[17] On January 13, 1922 the university was issued its new license, which was given the randomly assigned call letters WLB, and authorized the use of both broadcasting wavelengths: 360 meters (833 kHz) for "entertainment", and 485 meters (619 kHz) for "market and weather reports". This was the first broadcasting station license issued in the state of Minnesota. WHA, operated by the University of Wisconsin–Madison, was issued its first license on the same day, making WLB and WHA the first two broadcasting licenses issued to educational institutions, and early examples of college radio stations.[18] Other Midwestern universities also doing early telegraph and radio experiments include the University of Iowa's WSUI and Iowa State University's WOI, both started in 1911, and St. Louis University's WEW in 1912. WHA began its experiments in 1915.

In February 1922, when a heavy snowstorm knocked out newswire services in the region, the Minneapolis Tribune asked the station's operators to help retrieve the day's news through a roundabout series of amateur radio relays.[19]

Beginning in 1927[20] the station operated with a secondary call sign of "WGMS", for "Gold Medal (Flour) Station",[21] which was used when station WCCO employed WLB's transmitter. (At the time, WCCO was also using its own facilities at 720 kHz, 740 kHz and 810 kHz.)[22][23] On May 15, 1933, after the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) requested that stations using only one of their assigned call letters drop those that were no longer in regular use, WGMS was eliminated and the station reverted to just WLB.[24]

On November 11, 1928, a major reassignment of station transmitting frequencies took place, under the provisions of the Federal Radio Commission's General Order 40. WLB began operating on 1250 kHz, but a shortage of available assignments meant it had to share this frequency with three other stations: St. Olaf College's WCAL in Northfield, Minnesota; Carlton College's KFMX; and the Rosedale Hospital's WRHM, which in 1934 changed its callsign to WTCN (now WWTC). WLB, WCAL and KFMX were operated by educational institutions, while WTCN was a commercial station which aggressively sought to expand its operating hours at the expense of the other three stations.[25]

KFMX surrendered its license in 1933, which reduced the number of stations sharing time. WLB's facilities were moved to Eddy Hall in 1936. In 1938 WLB and WCAL made peace with WTCN by agreeing to move to 760 kHz, where the stations were restricted to daytime-only transmissions, with WLB to receive 2⁄3rds of the available hours.[26] In 1941, as part of the frequency shifts resulting from implementation of the North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement, WLB and WCAL moved from 760 to 770 kHz. In 1991, The University of Minnesota made an agreement with St. Olaf in which WCAL was provided land for an improved FM tower near Rosemount, Minnesota in exchange for fulltime use of the AM frequency.

WLB's programming was expanded to include lectures, concerts, and football games. In the 1930s and 1940s, the station broadcast a considerable amount of educational material and was used for distance learning—a practice that continued into the 1990s. On June 1, 1945, WLB's call sign was changed to KUOM, to stand for University of Minnesota.[27]

A polio epidemic in 1946 that resulted in temporary school closings and the cancellation of the Minnesota State Fair led the station to create programming for children who were homebound. Those programs, along with others broadcast in the 1940s, were recognized for their importance and led to several awards being given to the station.

Carrier current WMMR

[edit]

In 1948 a low-power student-run carrier current station was established, with studios in Coffman Memorial Union. Due to its very limited coverage, which was restricted to the campus and immediately adjoining areas, the station did not require a license from the Federal Communications Commission, or qualify for officially assigned call letters. However, it informally identified itself as WMMR for "Women's and Men's Minnesota Radio." Focused on providing a service for the student body, WMMR initially broadcast at 730 AM as "Radio 73". The programming was later also carried by the Minneapolis cable television system.

WMMR was a student-run operation and relied solely on volunteers. By the mid-1960s through the end of its life, WMMR tried to emulate the management structure of a typical AM rock station of the day, with an appointed General Manager, Program Director, Music Director and other management positions. A news and sports operation broadcast daily reports, and the basketball, football and hockey programs were usually broadcast with live play-by-play. A number of live broadcasts were done from the Whole Music Club and the Great Hall and the station promoted other campus events such as the 'Campus Carny' held annually in the old field house. Garrison Keillor, the well-known creator of Minnesota Public Radio's A Prairie Home Companion, began his radio career broadcasting classical music on WMMR as a student in the early 1960s. He then worked at KUOM from 1963 to 1968.

WMMR ended operations in 1993 with the launch of Radio K.

Radio K

[edit]

Until the change to Radio K in 1993, KUOM operated with a paid staff, and was known as "University of Minnesota Public Radio" (unrelated to Minnesota Public Radio). The station broadcast public affairs, arts, classical music, and a variety of other programming focusing especially on bringing the rich resources of the University to listeners. During its public service broadcast era, the station won many prestigious national awards and widespread recognition for its public service, news, and cultural and music programs. Daily programs and special broadcasts hosted many famed authors, political figures, musicians, actors, and scientists. Weekend programming was more casual and offered contemporary music, international music, and rock music programming, including what is likely the very first public broadcast of music by Prince.

In August 1991, the University began to examine the idea of merging WMMR and KUOM under political pressure from competing commercial and public radio broadcasters. The University explained the elimination of educational, cultural, and community outreach programming by claiming the public service format was too expensive, and that the new format would lower costs. It was also claimed that most of the educational value of KUOM had been superseded by other media outlets by this time, however no studies or research were done to substantiate these claims and no other broadcasting service in the state leveraged the resources of the University for public service. To avoid the lack of direction found at some college music stations, the new "Radio K" retained most full-time staff to oversee operations and provide a level of continuity, with students providing much of the on-air hosting. The transition took place in 1993, and KUOM began using the "Radio K" name on October 1 of that year.

One notable program in the first decade of Radio K was Cosmic Slop. The show, which first went on the air in the waning days of WMMR, searched through the station's considerable library of 1970s pop music, playing both the best and worst from that decade (with occasional forays into the recordings from the rest of the 20th century).[28]

KUOM-FM, with 6 watts at 106.5 FM, began operating in 2002 and is a simulcast of KUOM. At one point, this station was licensed to broadcast only during the time periods when its timeshare partner KDXL was off the air. KDXL, which began broadcasting in 1978, was owned by the St. Louis Park Public Schools district and operated by and from St. Louis Park High School during the hours of 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. on "designated school days," so outside of the summer months KUOM-FM generally operated only at night and on weekends.[29]

Setting up KUOM-FM took several years of negotiations with the FCC. In 2004, the transmitter was moved from the high school to a high rise residential building near Bde Maka Ska in southwest Minneapolis near the St. Louis Park city limits. The new site offered greatly increased height, therefore expanding the signal's range. Even with the additional height, the station operates at such low power that it can be heard clearly only within two to three miles of the transmitter. While southwest Minneapolis gets a fairly strong signal, this signal only provides fringe coverage in St. Paul at best (subject to occasional interference from a 197-watt translator of Christian contemporary outlet "The Refuge" in the southern suburb of Elko New Market), and cannot be heard at all in the Minneapolis-St. Paul suburbs except under rare circumstances or with a sensitive receiver.[30] In 2018, KDXL turned in its license, allowing KUOM-FM to broadcast full time, ending the time share agreement between the two stations.

The station's programming has been recognized as the "best radio station of the Twin Cities" in 2010,[31] 2013,[32] and 2015[33] by City Pages editors. Pitchfork founder Ryan Schreiber also commonly cites the station's influence as having been an integral factor in his decision to start an online publication dedicated to the coverage of independent music.

Funding

[edit]Radio K is a non-commercial educational radio station. It receives funding from a number of sources, including donations from listeners. Approximately 40% of the station's funding comes from listener support, while the rest is provided by the state and federal governments, along with the University of Minnesota.

KUOM is a member of AMPERS, the Association of Minnesota Public Educational Radio Stations.[34]

FM signals

[edit]KUOM is also available via low-power KUOM-FM St. Louis Park (106.5 FM), along with translators W264BR Falcon Heights (100.7 FM) and K283BG Minneapolis (104.5 FM).[35][36]

| Call sign | Frequency | City of license | Facility ID | Class | ERP (W) | Height (m (ft)) | Transmitter coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KUOM-FM | 106.5 FM | St. Louis Park, Minnesota | 122699 | D | 6 | 63.4 m (208 ft) | 44°56′47.3″N 93°19′24.9″W / 44.946472°N 93.323583°W |

| Call sign | Frequency | City of license | FID | ERP (W) | HAAT | Class | FCC info |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W264BR | 100.7 FM | Falcon Heights, Minnesota | 142994 | 99 | 186.2 m (611 ft) | D | LMS |

| K283BG | 104.5 FM | Minneapolis, Minnesota | 143025 | 99 | 63.1 m (207 ft) | D | LMS |

See also

[edit]- WDSE-FM – University of Minnesota station in Duluth

- KUMM – University of Minnesota station in Morris

References

[edit]- ^ "Facility Technical Data for KUOM". Licensing and Management System. Federal Communications Commission.

- ^ "Map of Effective Ground Conductivity in the United States for AM Broadcast Stations" (FCC.gov)

- ^ "Best Local Music Broadcast: Radio K's Off the Record". citypages.com. City Pages Best of the Twin Cities 2011.

- ^ "Best Local Music Broadcast: Radio K's Off the Record". citypages.com. City Pages Best of the Twin Cities 2012.

- ^ "Access Minnesota". accessminnesotaonline.com. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Welcome". Minnesota Broadcasters Association. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Radio history at the U of M" by Rebecca Toov, January 13, 2016 (continuum.umn.edu)

- ^ "Wireless to Flash Minnesota-Iowa Basketball Score", Minneapolis Tribune, January 21, 1916, page 13.

- ^ "New Stations: War Department Training and Rehabilitation Schools", Radio Service Bulletin, December 1, 1919, page 5.

- ^ "New Stations: Special Land Stations", Radio Service Bulletin, April 1, 1920, page 5. The "9" in 9XI's call sign indicated that the station was located in the ninth Radio Inspection district, while the "X" signified that the station was operating under an Experimental license.

- ^ The same equipment was used for both station operations. A photograph of the 9XI-WX2 transmitting equipment is included at the "Radio history at the U of M" webpage.

- ^ C. M. Jansky had previously been at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he had worked at its experimental station 9XM.

- ^ Radio Education Pioneering in the Mid-west by Albert A. Reed, 1942, page 74.

- ^ "'U' Wireless Station Has Market Service", Minneapolis Tribune, February 6, 1921, page 35.

- ^ The First Quarter-century of American Broadcasting by E. P. J. Shurick, 1946, page 115.

- ^ "Live Stock Prices by Wireless at 'U'", Minneapolis Tribune, December 4, 1921, page 1.

- ^ "Amendments to Regulations", Radio Service Bulletin, January 3, 1922, page 10.

- ^ "New Stations: Commercial Land Stations", Radio Service Bulletin, February 1, 1922, page 2. At this time there was no differentiation between commercial and non-commercial broadcasting stations. The licenses were not time-stamped, however WLB's Limited Commercial license serial number was #275, and WHA's was #276.

- ^ Charles William Taussig (1922). The Book of Radio. pp. 199–201. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ FCC History Cards: KUOM (image #2), "Broadcasting Station License Record: Card #1".

- ^ Requested Broadcast Calls of the 1920s by Jeff Miller

- ^ FCC History Cards: WCCO (image #3), "Construction Permit and License Record" (back of "Broadcasting Station License Record: Card #1")

- ^ "United States Broadcasting Stations", White's Radio Log, Fall and Winter Issue, 1930, page 3.

- ^ "Double Call Letters Are Being Eliminated", Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, June 25, 1933, Part 4, page 6.

- ^ "University of Minnesota", Education's Own Stations by S. E. Frost, Jr., pp. 215–218.

- ^ "WTCN Goes Full Time: College Stations Improve", Broadcasting, May 15, 1938, page 36.

- ^ "Three-Letter Roll Call" by Thomas H. White (earlyradiohistory.us). When WLB was first licensed in 1922, the dividing line for eastern "W" call letters and western "K" call signs ran along the western borders of the Dakotas. In January 1923 the boundary was shifted to the Mississippi River, which moved Minneapolis into the "K" call letters region.

- ^ "Cosmic Slop Home Page!". stitzel.com. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Annual Notification of Sharetime Schedule" (radiok.org)

- ^ "Twin Cities FM DX log". Ubstudios.com. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Best Radio Station: Radio K (104.5 FM, 100.7 FM, 106.5 FM, 770 AM)". citypages.com. City Pages Best of the Twin Cities 2010.

- ^ "Best Radio Station: Radio K". citypages.com. City Pages Best of the Twin Cities 2013.

- ^ "Best Radio Station: Radio K". citypages.com. City Pages Best of the Twin Cities 2015.

- ^ "Stations and Coverage Map". ampers.org. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "Twin Cities Class D FM Stations". NorthPine.com. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ Radio K FM Coverage Map (radiok.org)

External links

[edit]- Official website

- FCC History Cards for KUOM (covering 1927-1980 as WLB / WLB-WGMS / WLB / KUOM)

- Facility details for Facility ID 69337 (KUOM) in the FCC Licensing and Management System

- KUOM in Nielsen Audio's AM station database

- Facility details for Facility ID 143025 (K283BG) in the FCC Licensing and Management System

- K283BG at FCCdata.org

- Facility details for Facility ID 142994 (W264BR) in the FCC Licensing and Management System

- W264BR at FCCdata.org

- Hennepin County Public Library historical photos of WLB, 1939-40 search for "WLB"

- Minnesota Historical Society historical photos of KUOM, mid 1940s

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch