Lehigh Valley Railroad

| |

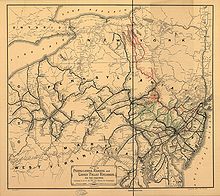

Map of Lehigh Valley Railroad routes | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Lehigh Valley Railroad Headquarters Building, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Reporting mark | LV |

| Locale | New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania |

| Dates of operation | 1846–1976 |

| Successor | Conrail (main line and branches lines were transferred to Norfolk Southern Railway and CSX; remaining Locomotives to Norfolk Southern) |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

The Lehigh Valley Railroad (reporting mark LV) was a railroad in the Northeastern United States built predominantly to haul anthracite coal from the Coal Region in Northeastern Pennsylvania to major consumer markets in Philadelphia, New York City, and elsewhere.

On April 21, 1846, the railroad was authorized to provide freight transportation of passengers, goods, wares, merchandise, and minerals[1] in Pennsylvania. On September 20, 1847, the railroad was incorporated and established, initially called the Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill and Susquehanna Railroad Company.

On January 7, 1853, the railroad's name was changed to Lehigh Valley Railroad.[2] It was sometimes known as the Route of the Black Diamond; black diamond is a slang word for anthracite, the high-end type of Pennsylvania coal that it initially transported by boat down the Lehigh River.

The Lehigh Valley Railroad's original and primary route between Easton and Allentown was built in 1855. The line later expanded past Allentown to Lehigh Valley Terminal in Buffalo and past Easton to New York City, bringing the Lehigh Valley Railroad to these metropolitan areas. By December 31, 1925, the railroad controlled 1,363.7 miles of road and 3,533.3 miles of track. By 1970, this had dwindled to 927 miles of road and 1963 miles of track.

The first small repair shops for locomotives and cars were located in Delano, Wilkes-Barre, Weatherly, Hazleton, and South Easton. In 1902 these were mostly consolidated into the shops at Sayre, Pennsylvania on the New York State border, which featured a 750 by 336-foot machine shop with 48 erecting pits. The shops in Packerton, Pennsylvania, located in the Coal Region north of Allentown, served as the primary freight car shops.

Conrail maintained the line as a main line into the New York metropolitan area, and the line became known as the Lehigh Line during Conrail's ownership of it. In 1976, Conrail abandoned most of the route in New York state to Buffalo, considerably shortening the line.

The majority of the Lehigh Line is now owned by the Norfolk Southern Railway (NS) and retains much of its original route in eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, although it no longer goes into New York City. The former Lehigh Valley tracks between Manville, New Jersey, and Newark are operated separately by Conrail Shared Assets Operations as their own Lehigh Line.

In 1976, the railroad ended operations and merged into Conrail along with several northeastern railroads that same year.

History

[edit]

19th century

[edit]The Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill and Susquehanna Railroad (DLS&S) was authorized by the Pennsylvania General Assembly on April 21, 1846, to construct a railroad from Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, now Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, to Easton, Pennsylvania. The railroad would run parallel to the Lehigh River and break the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company's monopoly on coal traffic from Wyoming Valley. The railroad was chartered on August 2, 1847, and elected James Madison Porter its president on October 21.[3]

Little occurred between 1847 and 1851, save some limited grading near Allentown, Pennsylvania.[4] All this changed in October 1851, when Asa Packer took majority control of the DLS&S. Packer brought additional financing to the railroad, installed Robert H. Sayre as chief engineer, and renamed the company the "Lehigh Valley Railroad." Construction began in earnest in 1853, and the line opened between Easton and Allentown on June 11, 1855. The section between Allentown and Mauch Chunk opened on September 12.[5]

At Easton, the LVRR interchanged coal at the Delaware River where coal could be shipped to Philadelphia on the Delaware Division Canal or transported across the river to Phillipsburg, New Jersey, where the Morris Canal and the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ) could carry it to the New York City market. At Easton, the LVRR constructed a double-decked bridge across the Delaware River for connections to the CNJ and the Belvidere Delaware Railroad in Phillipsburg.[6]

Through a connection with the Central Railroad of New Jersey, LVRR passengers had a route to Newark, New Jersey, Jersey City, New Jersey, and other points in New Jersey.[1]

The LVRR's rolling stock was hired from the Central Railroad of New Jersey and a contract was made with the CNJ to run two passenger trains from Easton to Mauch Chunk connecting with the Philadelphia trains on the Belvidere Delaware Railroad. A daily freight train was put into operation leaving Easton in the morning and returning in the evening. In the early part of October 1855, a contract was made with Howard & Co. of Philadelphia to do the freighting business of the railroad (except coal, iron, and iron ore).[1]

The length of the line from Mauch Chunk to Easton was 46 miles of single track. The line was laid with a rail weighing 56 pounds per yard supported upon cross ties 6 x 7 inches and 7-1/2 feet long placed 2 feet apart and about a quarter of it was ballasted with stone or gravel. The line had a descending or level grade from Mauch Chunk to Easton and with the exception of the curve at Mauch Chunk had no curve of less than 700 feet radius.[1] The 46-mile-long (74 km) LVRR connected at Mauch Chunk with the Beaver Meadow Railroad. The Beaver Meadow Railroad had been built in 1836, and it transported anthracite coal from Jeansville in Pennsylvania's Middle Coal Field to the Lehigh Canal at Mauch Chunk. For 25 years the Lehigh Canal had enjoyed a monopoly on downstream transportation and was charging independent producers high fees. When the LVRR opened, those producers eagerly sent their product by the railroad instead of canal, and within two years of its construction the LVRR was carrying over 400,000 tons of coal annually. By 1859 it had 600 coal cars and 19 engines.[6]

The LVRR immediately became the trunk line down the Lehigh Valley, with numerous feeder railroads connecting and contributing to its traffic. The production of the entire Middle Coal Field came to the LVRR over feeders to the Beaver Meadow: the Quakake Railroad, the Catawissa, Williamsport and Erie Railroad, the Hazleton Railroad, the Lehigh Luzerne Railroad and other smaller lines. At Catasauqua, the Catasauqua and Fogelsville Railroad transported coal, ore, limestone and iron for furnaces of the Thomas Iron Company, the Lehigh Crane Iron Company, the Lehigh Valley Iron Works, the Carbon Iron Company, and others. At Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, the North Pennsylvania Railroad which was completed during the Summer of 1856, provided a rail connection to Philadelphia and thus brought the LVRR a direct line to Philadelphia. At Phillipsburg, New Jersey, the Belvidere Delaware Railroad connected to Trenton, New Jersey.[6] To accommodate the 4 ft 10 in (1,473 mm) gauge of the Belvidere, the cars were furnished with wheels having wide treads that operated on both roads.[7]

The 1860s saw an expansion of the LVRR northward to the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, area and up the Susquehanna River to the New York state line.

Asa Packer was elected President of the Lehigh Valley Railroad on January 13, 1862.

In 1864, the LVRR began acquiring feeder railroads and merging them with its system. The first acquisitions were the Beaver Meadow Railroad and Coal Company, which included a few hundred acres of coal land, and the Penn Haven and White Haven Railroad. The purchase of the Penn Haven and White Haven was the first step in expanding to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. To reach Wilkes-Barre, the LVRR began constructing an extension from White Haven, Pennsylvania, to Wilkes-Barre. The Penn Haven and White Haven Railroad allowed the LV to reach White Haven.

In 1866, the LVRR purchased acquired the Lehigh and Mahanoy Railroad (originally the Quakake Railroad) and the North Branch Canal along the Susquehanna River, renaming it the Pennsylvania and New York Canal & Railroad Company (P&NY).[8] The purchasing of the North Branch Canal saw an opportunity for a near monopoly in the region north of the Wyoming Valley. In 1866, two years after the purchase of the Penn Haven and White Haven, the extension from White Haven to Wilkes-Barre opened.[1]

Construction of a rail line to the New York state line started immediately and, in 1867, the line was complete from Wilkes-Barre to Waverly, New York, where coal was transferred to the broad gauge Erie Railroad and shipped to western markets through Buffalo, New York.[1][9] To reach Wilkes-Barre, the LVRR purchased the Penn Haven & White Haven Railroad in 1864, and began constructing an extension from White Haven to Wilkes-Barre that was opened in 1867. By 1869, the LVRR owned a continuous track through Pennsylvania from Easton to Waverly.

In the following year, the LVRR—a standard gauge railroad—completed arrangements with the Erie Railroad, at that time having a six-foot gauge, for a third rail within the Erie mainline tracks to enable the LV equipment to run through to Elmira and later to Buffalo.[1]

Further rounds of acquisitions took place in 1868. The acquisitions in 1868 were notable because they marked the beginning of the LVRR's strategy of acquiring coal lands to ensure production and traffic for its own lines. Although the 1864 acquisition of the Beaver Meadow had included a few hundred acres of coal land, by 1868 the LVRR was feeling pressure from the Delaware and Hudson and the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad in the northern Wyoming Valley coal field, where the railroads mined and transported their own coal at a much reduced cost.[10] The LVRR recognized that its own continued prosperity depended on obtaining what coal lands remained. In pursuit of that strategy, the 1868 purchases of the Hazleton Railroad and the Lehigh Luzerne Railroad brought 1,800 acres (7.3 km2) of coal land to the LVRR, and additional lands were acquired along branches of the LVRR.[11] Over the next dozen years the railroad acquired other large tracts of land: 13,000 acres (53 km2) in 1870,[9] 5,800 acres (23 km2) in 1872,[12] and acquisition of the Philadelphia Coal Company in 1873 with its large leases in the Mahanoy basin. In 1875, the holdings were consolidated into the Lehigh Valley Coal Company, which was wholly owned by the LVRR.[2][13] By 1893, the LVRR owned or controlled 53,000 acres (210 km2) of coal lands.[13] With these acquisitions, the LVRR obtained the right to mine coal as well as transport it.[14]

The 1870s witnessed commencement of extension of the LVRR in a new direction.[1] In the 1870s the LVRR acquired other large tracts of land starting at 13,000 acres (53 km2) in 1870,[9] with an additional of 5,800 acres (23 km2) in 1872,[12] and turned its eye toward expansion across New Jersey all the way to the New York City area. In 1870, the Lehigh Valley Railroad acquired trackage rights to Auburn, New York, on the Southern Central Railroad.[1]

The most important market in the east was New York City, but the LVRR was dependent on the CNJ and the Morris Canal for transport to the New York tidewater. In 1871, the LVRR leased the Morris Canal, which had a valuable outlet in Jersey City on the Hudson River opposite Manhattan.[15] Asa Packer purchased additional land at the canal basin in support of the New Jersey West Line Railroad, which he hoped to use as the LVRR's terminal. That project failed, but the lands were later used for the LVRR's own terminal in 1889.

The CNJ, anticipating that the LVRR intended to create its own line across New Jersey, protected itself by leasing the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad (L&S) to ensure a continuing supply of coal traffic. The L&S had been chartered in 1837 by the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company (the Lehigh Canal company) to connect the upper end of the canal at Mauch Chunk to Wilkes-Barre.[16] After the LVRR opened its line, the Lehigh & Susquehanna extended to Phillipsburg, New Jersey, and connected with the CNJ and the Morris and Essex Railroad in 1868.[17] In 1871, the entire line from Phillipsburg to Wilkes-Barre was leased to the CNJ.[18] For most of its length, it ran parallel to the LVRR.

The LVRR found that the route of the Morris Canal was impractical for use as a railroad line, so in 1872 the LVRR purchased the dormant charter of the Perth Amboy and Bound Brook Railroad which had access to the Perth Amboy, New Jersey, harbor, and added to it a new charter, the Bound Brook and Easton Railroad. The State of New Jersey passed legislation that allowed the LVRR to consolidate its New Jersey railroads into one company; the Perth Amboy and Bound Brook and the Bound Brook and Easton were merged to form a new railroad company called the Easton and Amboy Railroad (or Easton & Amboy Railroad Company).[1][19][better source needed][20]

The Easton and Amboy Railroad was a railroad built across central New Jersey by the Lehigh Valley Railroad to run from Phillipsburg, New Jersey, to Bound Brook, New Jersey, and it was built to connect the Lehigh Valley Railroad coal-hauling operations in Pennsylvania and the Port of New York and New Jersey to serve consumer markets in the New York metropolitan area, eliminating the Phillipsburg connection with the CNJ that had previously been the only outlet to the New York tidewater; until it was built, the terminus of the LVRR had been at Phillipsburg on the Delaware River opposite Easton, Pennsylvania. The Easton and Amboy was used as a connection to the New York metropolitan area, with a terminus in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Construction commenced in 1872 as soon the Easton and Amboy was formed; coal docks at Perth Amboy were soon constructed, and most of the line from Easton to Perth Amboy was graded and rails laid. However, the route required a 4,893-foot (1,491 m) tunnel through/under Musconetcong Mountain near Pattenburg, New Jersey (about twelve miles east of Phillipsburg),[21] and that proved troublesome, delaying the opening of the line until May 1875,[22] when a coal train first passed over the line. To support the expected increase in traffic, the wooden bridge over the Delaware River at Easton was also replaced by a double-tracked, 1,191-foot (363 m) iron bridge.[23]

At Perth Amboy, a tidewater terminal was built on the Arthur Kill comprising a large coal dock used to transport coal into New York City. These tracks were laid and the Easton and Amboy Railroad was opened for business on June 28, 1875, with hauling coal. The Easton and Amboy's operations were labeled the "New Jersey Division" of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. The Easton and Amboy had already completed large docks and facilities for shipping coal at Perth Amboy upon an extensive tract of land fronting the Arthur Kill. Approximately 350,000 tons of anthracite moved to Perth Amboy during that year for transshipment by water.[1] Operations continued until the LVRR's bankruptcy in 1976.[24] The marshalling yard is now the residential area known as Harbortown.

Passenger traffic on the LVRR's Easton and Amboy connected with the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) at Metuchen, New Jersey, and continued to the PRR'S Exchange Place terminus in Jersey City; that connection was discontinued in 1891 after the LVRR established its own route to Jersey City from South Plainfield. The Easton and Amboy Railroad was absorbed into the parent Lehigh Valley Railroad.

In 1875, the LVRR financed the addition of a third rail to the Erie Railroad main line so that cars could roll directly from colliery to the port at Buffalo.[25] While the third rail on the Erie Railroad main line between Waverly and Buffalo gave the LVRR an unbroken connection to Buffalo, the road's management desired its own line into Buffalo. The Geneva, Ithaca & Athens Railroad passed into the hands of the LVRR in September 1876, which extended from the New York state line near Sayre, Pennsylvania, to Geneva, New York, a distance of 75 miles.[1]

On May 17, 1879, Asa Packer, the company's founder and leader, died at the age of 73. At the time of his death, the railroad was shipping 4.4 million tons of coal annually over 657 miles (1,057 km) of track, using 235 engines, 24,461 coal cars, and over 2,000 freight cars of various kinds. The company controlled 30,000 acres (120 km2) of coal-producing lands and was expanding rapidly into New York and New Jersey.[26] The railroad had survived the economic depression of 1873 and was seeing its business recover. Leadership of the company transferred smoothly to Charles Hartshorne, who had been vice president under Packer. In 1883, Hartshorne retired to allow Harry E. Packer, Asa's 32-year-old youngest son, to assume the Presidency.[14] A year later, Harry Packer died of illness, and Asa's 51-year-old nephew Elisha Packer Wilbur was elected president, a position he held for 13 years.[27]

The 1880s continued to be a period of growth, and the LVRR made important acquisitions in New York, expanded its reach into the southern coal field of Pennsylvania which had hitherto been the monopoly of the Reading, and successfully battled the CNJ over terminal facilities in Jersey City.

In 1880, the LVRR established the Lehigh Valley Transportation Line to operate a fleet of ships on the Great Lakes with terminals in Chicago, Milwaukee, and Duluth. This company became an important factor in the movement of anthracite, grain and package freight between Buffalo, Chicago, Milwaukee, Duluth, Superior and other midwestern cities. Following Federal legislation which stopped the operation of such service, the lake line was sold to private interests in 1920.[1]

The port on Lake Erie at Buffalo was critical to the LVRR's shipments of coal to western markets and for receipt of grain sent by the West to eastern markets. Although in 1870 the LVRR had invested in the 2-mile (3.2 km) Buffalo Creek Railroad, which connected the Erie to the lakefront, and had constructed the Lehigh Docks on Buffalo Creek, it depended on the Erie Railroad for the connection from Waverly to Buffalo, New York.[9]

In 1882, the LVRR began an extensive expansion into New York from Sayre, Pennsylvania (just southeast of Waverly) to Buffalo. Construction from Sayre to Buffalo was split into two projects, Sayre to Geneva, New York, and Geneva, which is located at the northern end of Seneca Lake), to Buffalo. First, it purchased a large parcel of land in Buffalo, the Tifft farm, for use as terminal facilities, and obtained a New York charter for the Lehigh Valley Railway, a similar name to the LVRR, but with "railway" instead.[28] LVRR subsidiary, Lehigh Valley Railway began constructing the main line's northern part from Buffalo to Lancaster, New York, in 1883, a total distance of ten miles. This was the second step toward establishment of a direct route from Sayre to Buffalo (thus avoiding the connecting spur to Waverly and on to Buffalo on the Erie), the first being the acquisition of the Geneva, Ithaca & Athens Railroad.

In 1887, the Lehigh Valley Railroad obtained a lease on the Southern Central Railroad (the LVRR previously had trackage rights on the railroad starting in 1870), which had a route from Sayre northward into the Finger Lakes region.[29] At the same time, the LVRR organized the Buffalo and Geneva Railroad to build the rest of the 97-mile Geneva to Buffalo trackage, from Geneva to Lancaster. Finally, in 1889, the LVRR gained control of the Geneva, Ithaca, and Sayre Railroad and completed its line of rail through New York.[30] As a result of its leases and acquisitions, the Lehigh Valley gained a near-monopoly on traffic in the Finger Lakes region.

It also continued to grow and develop its routes in Pennsylvania. In 1883 the railroad acquired land in northeast Pennsylvania and formed a subsidiary called The Glen Summit Hotel and Land Company. It opened a hotel in Glen Summit, Pennsylvania, called the Glen Summit Hotel to serve lunch to passengers traveling on the line. The hotel remained with the company until 1909, when it was bought by residents of the surrounding cottages.[31]

In New York State, s branch line, the Hayts Corners, Ovid & Willard Railroad opened May 14, 1883 from the Geneva, Ithaca & Sayre to the Willard asylum, and continued in service until 1936.[32]

In Pennsylvania, the Lehigh scored a coup by obtaining the charter formerly held by the Schuykill Haven and Lehigh River Railroad in 1886. That charter had been held by the Reading Railroad since 1860, when it had blocked construction in order to maintain its monopoly in the Southern Coal Field. That southern field held the largest reserves of anthracite in Pennsylvania and accounted for a large percentage of the total production. Through neglect, the Reading allowed the charter to lapse, and it was acquired by the Lehigh Valley, which immediately constructed the Schuylkill and Lehigh Valley Railroad. The line gave the LVRR a route into Pottsville, Pennsylvania, and the Schuylkill Valley coal fields.[33]

The Vosburg Tunnel was completed and opened for service on July 25, 1886. The 16-mile mountain cut-off, a rail segment of the line that extended from Fairview, Pennsylvania, to the outskirts of Pittston, Pennsylvania, was completed in November 1888. This allowed the line's eastbound grade to be reduced and a shorter route for handling through traffic established.

The LVRR had built coal docks in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, when it built the Easton and Amboy in the 1870s, but desired a terminal on the Hudson River close to New York City. In New Jersey, the LVRR embarked on a decade-long legal battle with the CNJ over terminal facilities in Jersey City. The land that Asa Packer had obtained in 1872 was situated on the southern side of the Morris Canal's South Basin, but the CNJ already had its own facilities adjacent to that property and disputed the LVRR's title, which partly overlapped land the CNJ had filled for its own terminal.[34]

Finally in 1887 the two railroads reached a settlement, and construction of the LVRR's Jersey City freight yard began.[35] The LVRR obtained a 5-year agreement to use the CNJ line to access the terminal, which opened in 1889. It fronted the Morris Canal Basin with a series of 600-foot (180 m) piers angling out from the shoreline but was too narrow for a yard, so the LVRR built a separate yard at Oak Island in Newark to sort and prepare trains. The South Basin terminal was used solely for freight, having docks and car float facilities. Passengers were routed to the Pennsylvania Railroad's terminal and ferry.

The LVRR strove throughout the 1880s to acquire its own route to Jersey City and to the Jersey City waterfront. The LVRR decided to expand more to the Northeastern New Jersey in order to reach its freight yards without using the CNJ main line.

The LVRR began construction of a series of railroads to connect the Easton and Amboy line (Easton and Amboy Railroad) to Jersey City. The first leg of the construction to Jersey City was the Roselle and South Plainfield Railway in 1888 which connected with the CNJ at Roselle for access over the CNJ to the Hudson River waterfront in Jersey City. The LVRR, which had built coal docks in Perth Amboy when it built the Easton and Amboy in the 1870s, desired a terminal on the Hudson River close to New York City. In 1891, the LVRR consolidated the Roselle and South Plainfield Railway into the Lehigh Valley Terminal Railway, along with the other companies which formed the route from South Plainfield to the Jersey City terminal.

Initially, the LVRR contracted with the CNJ for rights from Roselle to Jersey City, but the LVRR eventually finished construction to its terminal in Jersey City over the Newark and Roselle Railway, the Newark and Passaic Railway, the Jersey City, Newark, and Western Railway, and the Jersey City Terminal Railway. The LVRR's Newark and Roselle Railway in 1891 brought the line from Roselle into Newark, where passengers connected to the Pennsylvania Railroad. Bridging Newark Bay proved difficult. The LVRR first attempted to obtain a right of way at Greenville, but the Pennsylvania Railroad checkmated them by purchasing most of the properties needed. Then the CNJ opposed the LVRR's attempt to cross its line at Caven Point. Finally after settling the legal issues, the Newark Bay was bridged in 1892 by the Jersey City, Newark and Western Railway and connected to the National Docks Railway, which was partly owned by the LVRR and which reached the LVRR's terminal.

In 1895, the LVRR constructed the Greenville and Hudson Railway parallel with the national docks in order to relieve congestion and have a wholly-owned route into Jersey City. Finally in 1900, the LVRR purchased the National Docks Railway outright.

The 1890s began with the completion of its terminals in Buffalo and Jersey City, and the establishment of a trunk line across New York state, the company soon became entangled in costly business dealings which ultimately led to the Packer family's loss of control.

The coal trade was always the backbone of the business but was subject to boom and bust as competition and production increased and the economy cycled. The coal railroads had begun in 1873 to form pools to regulate production and set quotas for each railroad. By controlling supply, the coal combination attempted to keep prices and profits high. Several combinations occurred, but each fell apart as one road or another abrogated its agreement. The first such combination occurred in 1873, followed by others in 1878, 1884, and 1886. Customers naturally resented the actions of the cartel, and since coal was critical to commerce, Congress intervened in 1887 with the Interstate Commerce Act that forbade the roads from joining into such pools. Although the roads effectively ignored the Act and their sales agents continued to meet and set prices, the agreements were never effective for long.

In 1892, the Reading Railroad thought it had a solution. Instead of attempting to maintain agreements among the coal railroads, it would purchase or lease the major lines and bring them into a monopoly. It leased the CNJ and the LVRR, purchased the railroads' coal companies and arranged for the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad to cooperate with the combination, thereby controlling 70% of the trade.[13][36] Unfortunately, it overreached and in 1893 was unable to meet its obligations. Its bankruptcy resulted in economic chaos, bringing on the financial panic of 1893 and forcing the LVRR to break the lease and resume its own operations, leaving it unable to pay dividends on its stock until 1904. The economic depression following 1893 was harsh, and by 1897 the LVRR was in dire need of support. The banking giant J. P. Morgan stepped in to refinance the LVRR debt and obtained control of the railroad in the process. Ousting President Elisha P. Wilbur and several directors in 1897, the Morgan company installed W. Alfred Walter as president and seated its own directors. In 1901, Morgan arranged to have the Packer Estate's holdings purchased jointly by the Erie, the Pennsylvania, the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, the DL&W and the CNJ, all companies in which Morgan had interests. Newly elected president Eben B. Thomas, formerly of the Erie, and his board of directors represented the combined interests of those railroads.[37]

A final attempt to establish a coal cartel took place in 1904 with the formation of the Temple Iron Company. Prior to that time, the Temple Iron Company was a small concern that happened to have a broad charter allowing it to act as a holding company. The Reading, now out of receivership, purchased the company and brought the other coal railroads into the partnership, with the Reading owning 30%, the LVRR 23%, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western 20%, CNJ 17%, Erie 6%, and New York, Susquehanna and Western 4 percent. The purpose of the Temple Iron Company was to lock-up independent coal production and control the supply. Congress reacted with the 1906 Hepburn Act, which among other things forbade railroads from owning the commodities that they transported. A long series of antitrust investigations and lawsuits resulted, culminating in a 1911 Supreme Court decision that forced the LVRR to divest itself of the coal companies it had held since 1868. The LVRR shareholders received shares of the now independent Lehigh Valley Coal Company, but the railroad no longer had management control of the production, contracts, and sales of its largest customer.

In 1896, the very early film Black Diamond Express was produced by Thomas A. Edison's company Kinetoscope. The train arrives from far away and passes the camera, while workers are waving their handkerchiefs.[38]

20th century

[edit]

Grain tonnage was increasing and the company transported large quantities from Buffalo to Philadelphia and other Eastern markets. Also, in 1914 the Panama Canal was completed, and the LVRR gained an important new market with ores shipped from South America to the Bethlehem Steel company. In order to handle the additional new ocean traffic, the LVRR created a large new pier at Constable Hook, which opened in 1915, and a new terminal at Claremont which opened in 1923.

It also built a passenger terminal in Buffalo in 1915. Since 1896 the LVRR had run an important and prestigious express train named the "Black Diamond" which carried passengers to the Finger Lakes and Buffalo. Additional passenger trains ran from Philadelphia to Scranton and westward. From the beginning, the LVRR's New York City passengers had used the Pennsylvania Railroad's terminal and ferry at Jersey City, but in 1913 the PRR terminated that agreement, so the LVRR contracted with the CNJ for use of its terminal and ferry, which was expanded to handle the increased number of passengers. The railroad also published a monthly magazine promoting travel on the train called the "Black Diamond Express Monthly".

In the war years 1914 to 1918, the Lehigh handled war materials and explosives at its Black Tom island facility, which had been obtained along with the National Docks Railroad in 1900. In 1916, a horrendous explosion occurred at the facility, destroying ships and buildings, and breaking windows in Manhattan. At first the incident was considered an accident; a long investigation eventually concluded that the explosion was an act of German sabotage, for which reparations were finally paid in 1979.

After the U.S. entered World War I, the railroads were nationalized in order to prevent strikes and interruptions. The United States Railroad Administration controlled the railroad from 1918 to 1920, at which time control was transferred back to the private companies. Although the heavy wartime traffic had left the railroad's plant and equipment in need of repair, the damage was partly offset by new equipment that had been purchased by the government.

In 1920, the LVRR sold its lake line company, the Lehigh Valley Transportation Line, to private interests due to new federal legislation which stopped the practice of railroads owning lake lines.[1]

Throughout the 1920s the railroad remained in the hands of the Morgan / Drexel banking firm, but in 1928 an attempt was made to wrest control from it. In 1927, Leonor Fresnel Loree, president of the Delaware and Hudson Railroad, had a vision for a new fifth trunk line between the East and West, consisting of the Wabash Railroad, the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railway, and the LVRR.[39] Through bonds issued by the D&H, he obtained 30% of the LVRR stock, and won the support of nearly half the stockholders. In 1928, he attempted to seat a new president and board. A massive proxy fight ensued, with existing President Edward Eugene Loomis narrowly retaining his position with the support of Edward T. Stotesbury of J. P. Morgan.[40]

Following the defeat of its plan, the D&H sold its stock to the Pennsylvania Railroad. In the following years, the Pennsylvania quietly obtained more stock, both directly and through railroads it controlled, primarily the Wabash. By 1931, the PRR controlled 51% of the LVRR stock. Following Loomis' death in 1937, the presidency went to Loomis' assistant Duncan J. Kerr,[41] but in 1940 he was replaced by Albert N. Williams,[42] and the road came under the influence of the PRR. In 1941, the Pennsylvania placed its shares in a voting trust after reaching an agreement with the New York Central regarding the PRR's purchase of the Wabash.[43]

Following the Great Depression, the railroad had a few periods of prosperity, but was clearly in a slow decline. Passengers preferred the convenience of automobiles to trains, and airlines much later provided faster long-distance travel than trains. Oil and gas were supplanting coal as the fuel of choice. The Depression had been difficult for all the railroads, and Congress recognized that bankruptcy laws needed revision. The Chandler Acts of 1938-9 provided a new form of relief for railroads, allowing them to restructure their debt while continuing to operate. The LVRR was approved for such a restructuring in 1940 when several large mortgage loans were due. The restructuring allowed the LVRR to extend the maturity of its mortgages, but it needed to repeat the process in 1950.[44] The terms of the restructurings precluded dividend payments until 1953, when LVRR common stock paid the first dividend since 1931.[45] In 1957, the LVRR again stopped dividends.[46]

In 1944, the LVRR's gross revenues came close to $100,000,000 which was a milestone for the railroad.[1]

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 273 |

| 1933 | 111 |

| 1944 | 453 |

| 1960 | 31 |

| 1970 | 0 |

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 5418 |

| 1933 | 2965 |

| 1944 | 9388 |

| 1960 | 2981 |

| 1970 | 2915 |

In the 1950s, the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1956, better known as the Interstate Highway Act, and the opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959, proved harmful to Lehigh Valley Railroad and the rest of the nation's rail industry. Interstate highways helped the trucking industry offer door-to-door service, and the St. Lawrence Seaway allowed grain shipments to bypass the railways and go directly to overseas markets. By the 1960s, railroads in the East were struggling to survive. The Pennsylvania Railroad in 1962 requested ICC authorization to acquire complete control of the LVRR through a swap of PRR stock for LVRR and elimination of the voting trust that had been in place since 1941.[47] It managed to acquire more than 85% of all outstanding shares, and from that time the LVRR was little more than a division of the PRR. The Pennsylvania merged with the New York Central in 1968, but the Penn Central failed in 1970, causing a cascade of railroad failures throughout the East.

On June 21, 1970, Penn Central declared bankruptcy and sought bankruptcy protection. As a result, the PC was relieved of its obligation to pay fees to various Northeastern railroads—the Lehigh Valley included—for the use of their railcars and other operations. Conversely, the other railroads' obligations to pay those fees to the Penn Central were not waived. This imbalance in payments would prove fatal to the financially-frail Lehigh Valley, and it declared bankruptcy just over one month after the Penn Central, on July 24, 1970.[48][note 1]

The Lehigh Valley Railroad remained in operation during the 1970 bankruptcy, as was the common practice of the time. In 1972, the Lehigh Valley Railroad assumed the remaining Pennsylvania trackage of the Central Railroad of New Jersey, a competing anthracite railroad which had entered bankruptcy as well. The two roads had entered a shared trackage agreement in this area in 1965 to reduce costs, as both had parallel routes from Wilkes-Barre virtually all the way to metropolitan New York, often on adjoining grades through Pennsylvania.

In the years leading to 1973, the freight railroad system in the northeast of the U.S. was collapsing. Although government-funded Amtrak took over intercity passenger service on May 1, 1971, railroad companies continued to lose money due to extensive government regulations, expensive and excessive labor cost, competition from other transportation modes, declining industrial business and other factors;[50] the Lehigh Valley Railroad was one of them.

Hurricane Agnes in 1972 damaged the rundown Northeast railway network, which put the solvency of other railroads including the LVRR in danger; the somewhat more solvent Erie Lackawanna Railway (EL) was also damaged by Hurricane Agnes.

In 1973, the United States Congress acted to create a bill to nationalize all bankrupt railroads which included the LV. The Association of American Railroads, which opposed nationalization, submitted an alternate proposal for a government-funded private company. President Richard Nixon signed the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973 into law.[51] The "3R Act," as it was called, provided interim funding to the bankrupt railroads and defined a new "Consolidated Rail Corporation" under the AAR's plan.[citation needed]

On April 1, 1976, the LVRR, including its main line, was merged into the U.S. government's Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) ending 130 years of existence and 121 years of operation of the LVRR.

Surviving segments

[edit]Background

[edit]Conrail Ownership

[edit]On April 1, 1976, major portions of the assets of the bankrupt Lehigh Valley Railroad were acquired by Conrail.

This primarily consisted of the main line and related branches from Van Etten Junction (north of Sayre, Pennsylvania) to Oak Island Yard, the Ithaca branch from Van Etten Junction to Ithaca, New York, connecting to the Cayuga Lake line and on to the Milliken power station in Lake Ridge, New York (closed on August 29, 2019) and the Cargill salt mine just south of Auburn, and small segments in Geneva, New York(from Geneva to the Seneca Army Depot in Kendaia), Batavia, New York, Auburn, New York, and Cortland, New York. A long segment west from Van Etten Junction to Buffalo was included in the Conrail takeover, but was mostly torn-up not long afterward. A segment from Geneva to Victor, New York, later cut back to Shortsville, New York, to Victor, remained with the Lehigh Valley Estate under subsidized Conrail operation. The Shortsville to Victor segment became the Ontario Central Railroad in 1979 (the Ontario Central became part of the Finger Lakes Railway in October 2007[52]).

Most of the rail equipment went to Conrail as well, but 24 locomotives (units GP38-2 314-325 and C420 404–415) went to the Delaware & Hudson instead. The remainder of the assets were disposed of by the estate until it was folded into the non-railroad Penn Central Corporation in the early 1980s.

The route across Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Oak Island Yard remains important to the Norfolk Southern Railway and CSX Transportation today, the only two Class 1 railroads that are based in the Eastern United States. This route became important to Conrail as an alternate route to avoid Amtrak's former PRR/PC Northeast Corridor electrified route. Today, this route continues as two lines, one that is considered the original line that served as the main line for the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the other that is considered a new line that was once part of the original line that served as the main line for the Lehigh Valley Railroad. The original line retains its original route when it was first constructed and is served by Norfolk Southern Railway. The new line is also served by Norfolk Southern Railway, but it is served together with CSX Transportation in a joint ownership company called Conrail Shared Assets Operations. Most of the other remaining Lehigh Valley track serves as branch lines, or has been sold to short line and regional operators.

These operators include:

- Finger Lakes Railway/Ontario Central Railroad

- Genesee Valley Transportation Company (Depew, Lancaster & Western)

- Livonia, Avon and Lakeville Railroad

- New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway

- Reading Blue Mountain and Northern Railroad

The Lehigh Line

[edit]

The Lehigh Line was the Lehigh Valley Railroad's first rail line and served as the main line. It was opened on June 11, 1855, between Easton, Pennsylvania, and Allentown, Pennsylvania, passing through Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Three months later the line branched out to the northwest past Allentown to Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania (then known as Mauch Chunk), on September 12, 1855. The line was later extended out to the northwest past Jim Thorpe to the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, area and later it reached the Buffalo, New York, area and past Easton all the way to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and then switched direction to the northeast to Jersey City, New Jersey, later cut back to Newark, New Jersey.

During the early years, the line served as the body of the Lehigh Valley Railroad until the railroad either built, acquired, or merged other railroads into its system. During the majority of its ownership under the Lehigh Valley Railroad, the line was known as the Lehigh Valley Mainline, starting in the 1930s. The line and the rest of the Lehigh Valley Railroad was absorbed into Conrail in 1976 and was maintained as a main line into the New York City area.

The line became known as the Lehigh Line during Conrail ownership. Conrail integrated former CNJ main line leased trackage into the line and kept the line in continuous operation (since 1855); however, it downsized the line in the northwest from the Buffalo area of New York State: first to Sayre Yard in Sayre, Pennsylvania; then to Mehoopany, Pennsylvania; and finally to Penn Haven Junction in Lehigh Township, Carbon County, Pennsylvania. The line's being downsized three times created two new rail lines: the Lehigh Secondary and the Lehigh Division, which was later sold to the Reading Blue Mountain and Northern Railroad (RBMN) in 1996; the RBMN would later cut back the Lehigh Division from Mehoopany to Dupont, Pennsylvania. The tracks from Dupont to Mehoopany became a new rail line called the Susquehanna Branch.

In 1999, the Norfolk Southern Railway which is owned by the Norfolk Southern Corporation acquired the Lehigh Line in the Conrail split with CSX Transportation but the tracks from Manville, New Jersey, to Newark, New Jersey, were kept with Conrail in order for both Norfolk Southern and CSX to have equal competition in the Northeast. The existing tracks from Manville to Newark became a new rail line and Norfolk Southern along with CSX own it under a joint venture. However, for historical purposes, the part from Manville to Newark is considered a new rail line and the Norfolk Southern part is considered the original line. Now under ownership of the Norfolk Southern Railway, the Lehigh Line's route is now from Port Reading Junction in Manville, New Jersey, to Penn Haven Junction in Lehigh Township, Pennsylvania. This is currently the last time the line has been downsized.

Current operations

[edit]

The Lehigh Line still exists and still serves as a major freight railroad line that operates in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The line is still owned and operated by the Norfolk Southern Railway and the line still runs from Port Reading Junction in Manville, New Jersey, to Penn Haven Junction in Lehigh Township, Pennsylvania.[53]

The line connects with Conrail Shared Assets Operations's Lehigh Line, the new rail line, and CSX Transportation's Trenton Subdivision at Port Reading Junction in Manville, New Jersey, and connects with the Reading Blue Mountain and Northern Railroad's Reading Division at Packerton, Pennsylvania, and Reading Blue Mountain and Northern Railroad's Lehigh Division, originally M&H Junction, in Lehighton.

The line makes notable connections with other Norfolk Southern lines such as the Reading Line and independent shortline railroads.

At Three Bridges, New Jersey, in Readington Township, the line interchanges with Black River and Western Railroad. At Phillipsburg, New Jersey, the line interchanges with its New Jersey side branch line, the Washington Secondary and the Belvidere and Delaware River Railway which also passes over the Belvidere and Delaware River after that. Across the river in Easton, Pennsylvania, the line interchanges with its Pennsylvania side branch line, the Portland Secondary, which extends from Easton to Portland, Pennsylvania, connecting to the Stroudsburg Secondary, which was originally part of the Lackawanna Old Road (or simply Old Road); the Stroudsburg Secondary goes under the Lackawanna Cut-Off and connects with the Delaware-Lackawanna Railroad.

The line hosts approximately twenty-five trains per day, with traffic peaking at the end of the week. East of the junction with the Reading Line in Allentown and in Bethlehem, the line serves as Norfolk Southern's main corridor in and out of the Port of New York and New Jersey, and the New York Metro Area at large, as Norfolk Southern doesn't currently use the eastern half of its Southern Tier Line, which follows the Delaware River from Port Jervis north to Binghamton, New York, and which is now (2022) operated by the Central New York Railroad. The line is part of Norfolk Southern's Harrisburg Division and it is part of Norfolk Southern's Crescent Corridor, a railroad corridor. It passes through the approximately 5,000-foot Pattenburg Tunnel in West Portal, New Jersey, along its route. Most of the traffic along the line consists of intermodal and general merchandise trains going to yards such as Oak Island Yard in Newark, New Jersey, and Croxton Yard in Jersey City.

The first locomotive purchased by the LVRR was the "Delaware", a wood-burning 4-4-0 built by Richard Norris & Sons of Philadelphia in 1855. It was followed by the "Catasauqua" 4-4-0 and "Lehigh" 4-6-0, which were also Norris & Sons engines. In 1856, the "E. A. Packer" 4-4-0 was purchased from William Mason of Taunton, Massachusetts. Subsequently, the LVRR favored engines from Baldwin Locomotive Works and William Mason, but tried many other designs as it experimented with motive power that could handle the line's heavy grades.[7]

- In 1866, Master Mechanic Alexander Mitchell designed the "Consolidation" 2-8-0 locomotive, built by Baldwin, which was to become a standard freight locomotive throughout the world. 2-8-0 pattern provided the traction needed for hauling heavy freight, but had a short enough wheelbase to manage curves.

- 1945: The first Lehigh Valley Railroad mainline diesels arrive in the form of EMD FT locomotives.

- 1948: ALCO PA passenger diesels replace steam on all passenger runs.

- 1951: September 14: Last day of steam on the Lehigh Valley Railroad as Mikado 432 drops her fire in Delano, Pennsylvania.

Passenger operations

[edit]The LVRR operated several named trains in the post-World War II era. Among them:

- No. 11 The Star

- No. 4 The Major

- No. 7/8 The Maple Leaf

- No. 9/10 The Black Diamond

- No. 23/24 The Lehighton Express

- No. 25/26 The Asa Packer, named for the LVRR's best-known president

- No. 28/29 The John Wilkes

The primary passenger motive power for the LVRR in the diesel era was the ALCO PA-1 car body diesel-electric locomotive, of which the LVRR had fourteen. These locomotives were also used in freight service during and after the era of LVRR passenger service. A pair of ALCO FA-2 FB-2 car body diesel-electric locomotives were also purchased to augment the PAs when necessary. These were FAs with steam generators, but they were not designated as FPA-2 units.

Due to declining passenger patronage, the Lehigh Valley successfully petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to terminate all passenger service. This took effect on February 4, 1961. The Maple Leaf and the John Wilkes were the last operating long-distance trains, terminated that day.[54] The only daylight New York-Buffalo train, the "Black Diamond", was discontinued in 1959. Budd Rail Diesel Car service would continue on a branch line (Lehighton-Hazleton) for an additional four days. The majority of passenger equipment is believed to have been scrapped some time after February 1961. Most serviceable equipment not retained for company service was sold to other roads.

Presidents

[edit]| Mayor | Term | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| James Madison Porter | 1847–1856 | James Madison Porter was the first President of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. |

| William Wilson Longstreth | 1856 | |

| John Gillingham Fell | 1856–1862 | |

| Asa Packer | 1862–1864 | This was his first term. |

| William Wilson Longstreth | 1864–1868 | |

| Asa Packer | 1868–1879 | This was his second term. |

| Charles Hartshorne | 1879–1882 | |

| Harry E. Packer | 1882–1884 | |

| Elisha Packer Wilbur | 1884–1897 | |

| W. Alfred Walter | 1897–1902 | |

| Eben B. Thomas | 1902–1917 | |

| Edward Eugene Loomis | 1917–1937 | [55] |

| Duncan J. Kerr | 1937–1939 | |

| R. W. Barrett | 1939 | |

| Albert N. Williams | 1939–1941 | |

| Revelle W. Brown | 1941–1944 | |

| Felix R. Gerard | 1944–1947 | |

| Cedric A. Major | 1947–1960 | |

| C. W. Baker | 1960 | |

| Colby M. Chester | 1960–1962 | He served as chairman of the board while the presidency was vacant until PRR takeover. |

| Allen J. Greenough | 1962–1965 | |

| John Francis Nash | 1965–1974 | Bankruptcy trustee July 1970–August 1974.[56] |

| Robert Haldeman | 1970–1976 | Bankruptcy trustee from August 1974 to April 1976. |

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gerard 1946

- ^ a b Transcript of Record No. 570. Records and briefs of the United States Supreme Court. October 10, 1908.

- ^ Archer 1977, p. 27

- ^ Archer 1977, p. 28

- ^ Archer 1977, pp. 31–32

- ^ a b c Henry 1860, pp. 395–400

- ^ a b Bulletin Issue 42. Railway & Locomotive Historical Society. 1937. Archived from the original on May 26, 2009.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 14, 1867.

- ^ a b c d Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 9, 1871.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 13, 1868.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 11, 1869.

- ^ a b Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 21, 1873.

- ^ a b c Testimony taken before the Special Senate Committee Relative to the Coal Monopoly. Documents of the Senate of the State of New York, 1893, Volume 1. 1893. pp. 529, 572.

- ^ a b "Harry E. Packer" (PDF). New York Times. February 2, 1884.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 8, 1872.

- ^ Jones 1914, p. 23

- ^ Jones 1914, p. 35

- ^ Jones 1914, p. 118

- ^ "The Lehigh Valley Railroad". njrails.tripod.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015.

- ^ Drinker 1883, p. 303

- ^ "NS - Musconetcong Tunnel". Bridgehunter.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015.

- ^ Treese 2014, p. 55

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 18, 1876.

- ^ Deas, Wayne L. "PERTH AMBOY'S REBIRTH TIED TO PROJECT" Archived 2017-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, August 16, 1987. May 4, 2015. "The first, already begun along the right of way of the Conrail and Lehigh Valley Railroads from Route 440, will consist of 168 condominium units. It will serve as a scenic entrance to Harbortown."

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 16, 1877.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 18, 1881.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 20, 1885.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 15, 1884.

- ^ People ex re. Lehigh & N. Y. R. Co. v. Sohmer, State Comptroller. The New York Supplement, Vol. 154 (New York State Reporter, Vol. 188). September 15, 1915. p. 1054.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 21, 1890.

- ^ Mountaintop Historical Society (2008). The History of Glen Summit Springs as of the year 2008.

- ^ "Chronological Listing of Important Events in Century of Lehigh Valley's History". The Valley News. April 25, 1946. p. 7. Retrieved September 16, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Into New Coal Fields" (PDF). New York Times. October 5, 1890.

- ^ "A Great Railroads Lands" (PDF). New York Times. February 15, 1880.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company. January 17, 1888.

- ^ Jones 1914, p. 52

- ^ Jones 1914, pp. 68–70

- ^ Joachim Biemann (ed.): Black Diamond Express eisenbahn-im-film.de, Eisenbahn im Film – Rail Movies, KE 110 (author pseudonym), 23 April 2000, version 11 December 2017, retrieved 23 April 2020. (German)

- ^ "Loree Plan Loses to 4-system Merger" (PDF). New York Times. April 6, 1928.

- ^ "Fight for Control of Lehigh on Today" (PDF). New York Times. January 17, 1928.

- ^ "E. E. Loomis is Dead" (PDF). New York Times. July 12, 1937.

- ^ "A. N. Williams Head of Lehigh Valley" (PDF). New York Times. January 17, 1940.

- ^ "Rival Roads Agree on Wabash Issue" (PDF). New York Times. June 13, 1941.

- ^ "Lehigh Revamping Authorized by ICC" (PDF). New York Times. February 9, 1949.

- ^ "Lehigh Valley Railroad to Retires $2,489,000 in 66-Year-Old Bonds" (PDF). New York Times. October 20, 1954.

- ^ "Dividend Omitted by Lehigh Valley" (PDF). New York Times. October 24, 1957.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Railroad Seeking all the Stock of Lehigh Valley" (PDF). New York Times. December 17, 1960.

- ^ "Lehigh Line Asks Reorganization" (PDF). New York Times. July 25, 1970.

- ^ Archer 1977, p. 297

- ^ Stover 1997, p. 226ff

- ^ Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973, Pub.L. 93-236, 87 Stat. 985, 45 U.S.C. § 741. Approved 1974-01-02. Note: The approved bill was also called the "Northeast Region Rail Services Act." Section 1 of Pub.L. 93–236 provided that the law may be cited as "Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973." See 45 U.S.C. 701 note.

- ^ STB Decision 10/05/2007 – FD_35062_0 Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Norfolk Southern Lehigh Line - Timetable" (PDF). parailfan.com. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ "Last of the Railroad - Era Passes Tonight as Lehigh Ends Service". Geneva Times. 1961. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ "E. E. Loomis is Dead. Railroad Leader. President of the Lehigh Valley System Through War, He Recently Retired". New York Times. July 12, 1937. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018.

- ^ "People and Business". The New York Times. August 7, 1974. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018.

References

[edit]- Archer, Robert F. (1977). The History of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Berkeley: Howell-North Books. ISBN 978-0-8310-7113-4.

- Drinker, Henry S. (1883). A Treatise on Explosive Compounds, Machine Rock Drills and Blasting. New York: John Wiley & Sons. OCLC 4817726.

- Gerard, Felix R. (1946). The Lehigh Valley Railroad 1846-1946: A Centenary Address. Newcomen address. New York: Newcomen Society of the United States. OCLC 4337049.

- Henry, Mathew Schropp (1860). History of the Lehigh Valley. Easton, Pennsylvania: Bixler & Corwin. OCLC 866132359.

- Jones, Eliot (1914). The Anthracite Coal Combination in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 875740753.

- Stover, John F. (1997) [1961]. American Railroads (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77658-3.

- Starr, Timothy (2022). The Back Shop Illustrated, Volume 1: Northeast and New England Regions. Privately printed.

- Treese, Lorett (2014). Railroads of New Jersey: Fragments of the Past in the Garden State Landscape. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4356-3.

- Lamb, Tammy. (1998). Lehigh Valley Railroad. Retrieved July 26, 2004.

- Mancuso, James. Lehigh Valley Railroad. Retrieved December 21, 2005.

- Schaller, Ed. Lehigh Valley Railroad Modeler. Retrieved December 22, 2005.

- Lawrence, Scot. Lehigh Valley Railroad Survivors. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- Campbell, John W. Lehigh Valley Railroad. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- Annual Report of the State Board of Assessors of the State of New Jersey, News Printing Co., 1889, p. 85. Google books

- News about Railroads, New York Times, Aug 27, 1891

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch