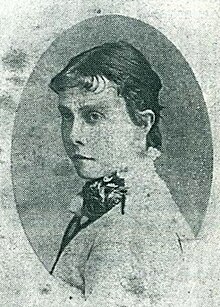

Lily Poulett-Harris

Lily Poulett-Harris (2 September 1873 – 15 August 1897) was an Australian sportswoman and educationalist, notable for being the founder and captain of the first women's cricket team in Australia.[1] Poulett-Harris continued to play until forced to retire due to ill health from tuberculosis that would eventually claim her life.

Early life

[edit]Born Harriet Lily Poulett-Harris (but referred to in all subsequent sources as Lily) on 2 September 1873, she was the youngest daughter of Richard Deodatus Poulett-Harris and his second wife, Elizabeth Eleanor (née Milward).[2] Her father was renowned for being the head of the Hobart Boys' High School and a founding father of the University of Tasmania, so it is no surprise that she and several of his other children followed him into careers in education.

As a young child Lily grew up in Hobart, where her father taught. Her mother was 31 and her father was 57 when Lily and her twin Violet were born. Lily's father was also a part-time rector at Holy Trinity Church of England, Hobart.[3] Lily grew up in this devout, resolutely high church environment.

Life must have been difficult at times for Lily growing up. Her father, who had arrived in Tasmania in 1856, was "melancholy in outlook and prone to depression, he had much sadness in his family life. He mourned the separation from the three daughters left in England [from his first marriage] and the early death of his son Richard from severe burns. His second daughter Charlotte Maria became of unsound mind, was committed to an institution in February 1872 and died a few years later."[4] (Note that this conflicts with the electoral roll and a Supreme Court record that establishes she died in the Lachlan Hospital at New Norfolk, in June 1941.)

Furthermore, "he was charged with assaulting boys with a cane in March 1860 and June 1868, the first case being dismissed and the second settled out of court, but he maintained the school's pre-eminent position in the colony until 1878 when he lost his midlands boarders to Horton College and Launceston Church Grammar School. Thereafter his health declined and in 1885, suffering acute physical pain and mental depression, he surrendered to Christ College, with the shareholders' agreement, all leasehold rights in return for an annuity of £300. The school was closed on 15 August 1885."[4]

A "a bright, inquisitive, adventurous and active child",[5] Lily was schooled by her father and received a Level II mark prize in December 1882.[6] Lily was allowed to sit the major exams as a "trial of strength" in 1884 even though she was not eligible for a scholarship. She came second.[7]

She also played the violin at school.[8] She would go on playing this instrument, and also the piano, all of her life, giving occasional public performances at Peppermint Bay[9] and Hobart. For instance, she gave a recital at a church choir fundraising event at her home parish of All Saints in South Hobart less than a year before she died.[10]

When her father retired in 1885, he purchased a hotel at Peppermint Bay (Woodbridge) and converted it into a house which he named "The Cliffs". Lily was to spend her adolescence and young adulthood here.

Saving her mother from fire

[edit]

However, the first indication of Lily's strength of character comes from November 1885, when she was twelve years old. One day, "Miss May Harris, with her two little sisters, Violet and Lily, and Miss Gaynor, a guest, went down to the beach to bathe, and a little while afterwards Mrs. Harris followed them down to look after them. On her way to the beach, and when, a little way only from it, her attention was caught by some brushwood and dry grass which she thought might harbour snakes. She accordingly set fire to it with the hope of removing it, and was still engaged in the operation, when she suddenly – the fire having spread without her noticing it – found that her dress had caught ablaze, and that the sleeves were burning. This was the first intimation she had of her danger, and she at once screamed out, and rolling herself on the ground, tried to put out the fire in that way. Lily, the younger of the twins, was the only one near enough to assist her mother, and rushing up, the little child had the presence of mind to pull off her wet bathing dress and wrap it round her mother's body, thus saving her from much worse injuries than those she received. Mrs Harris was taken home, and was found to be suffering from severe burns on the arms and back."[11]

Cricketing career

[edit]Lily's older brother, Henry Vere Poulett-Harris (1865–1933) was a gifted footballer, runner and cricketer,[12] and he eventually represented both Tasmania and Western Australia in first-class cricket in a career spanning the 1883–84 to 1898–1899 seasons.[13] (He later owned a Western Australian gold mine.) One early news report described him as a "sterling cricketer and footballer"[14] whilst another described him as a "sterling batsman and good field."[15]

Indeed, his obituary states that he was "one of the outstanding athletes in the State, winning great success as a runner, cricketer and footballer. He played cricket for the Wellington Club and was regarded as one of the most graceful batsmen in the State. He was a member of the State team when a youth, and toured New Zealand with the Tasmanian team under the captaincy of the late Sir George Davies. Later he met with success as a batsman on the mainland. He was also a champion footballer and a member of the Cricketers' Football Club, some of his contemporaries being Messrs. W. H. Cundy, L. H. Macleod, K. E. Burn, A. Stuart and G. Watt. As a runner he defeated many of the recognised champions of his day."[16] It was his interest in sport that appears to have spurred Lily on.

Another influence would have been her father who, in 1882, was elected a trustee of the Southern Tasmanian Cricket Association.[17] Furthermore, he encouraged the boys at the high school to compete at sports.[4]

As her own obituary notice states, Lily "was a great admirer of athletic exercises, firmly believing that it was very necessary to develop the physical as well as the mental part of our nature. Cricket had her warm sympathy and support... she was a good horsewoman and cyclist. Fear, it is said, was a thing unknown to her."[1]

Lily's cricket aspirations led her to found a cricket team for local women, the Oyster Cove Ladies' Cricket Club, in 1894. This was, according to a contemporary news report, the first female cricket club in the Australian colonies. She was unanimously elected captain and "she was remarkably successful in piloting her team to many a victory."[1] The other teams that were then established in the league included Atalanta (Hobart Quakers), Heather (Hobart) and North Bruny. The following year, Green Ponds,[18] Ranelagh and Huonville would join the competition.[19] As well as playing each other, the Ladies' team supported male cricketers by providing luncheons for them and playing music at concerts. These were most often held at Kettering's Selby Hall.[20] By the December of the following year, the ladies' competition had become well-established, a Hobart sports journalist noting that "[interest in cricket] seems to be growing, and extending to the weaker sex, who often have a quiet match upon a romantic little plateau on the Domain immediately beyond the upper cricket ground."[21]

Her sporting career is well-documented in the newspapers of the time. She was generally either the opening or third-order batswoman. The early sports journalism of the era consistently praised her performances, with such comments as a "prettily played innings"[22] on one occasion and, on another, "The feature of the match was undoubtedly the fine not out innings of Miss L. Poulett-Harris, captain of the winning team, who, going in first, carried her bat right through the innings for 64 runs."[23][24][25]

In May 1894, a Tasmanian correspondent for a Melbourne newspaper reported that "The ladies' cricketing season was concluded at Oyster Cove on 6 May, with a match between the Oyster Cove and North Bruni [sic] clubs, resulting in a win for the local team by an innings and 41 runs. The past season has been very successful, consequently, the outcome has been good cricket and high scoring. The captain of the Oyster Cove C. C., Miss L. Poulett-Harris, heads the batting list with the remarkably good average of 32.6; her batting throughout the season has been very good. She has also the honour of having put up the record for Tasmania, making 64 (not out) in an innings (which included five fours), and 78 in a match. Miss K. Denne, North Bruni C. C., comes next with an average of 18 runs."[26]

In 1895, Lily was described in one match as having "batted in good style, her contribution being well earned for the winners."[27]

She also bowled.[28] On one occasion her bowling was described by the Hobart Mercury's sports journalist as "very good indeed" when she got two opponents out for a total of one run between them.[24]

The teams did not adopt the "rational dress" that had become popular in some women's sports overseas by that time. Rather, "they all appear[ed] in prim summer dresses, and present[ed] a pretty picture."[21]

Teaching career

[edit]Lily's older sister, Eleanor (known as Nellie) had taught at the Hobart Ladies' College before teaching at her father's home[29][30] and then founding the Ladies' Grammar School and Kindergarten at 26 Davey Street in 1894 (opposite Franklin Square).[31][32][33][34] Lily and Violet were both to teach there.

Lily left Peppermint Bay to teach there in December 1894. At the time that she and her sister Nellie left, a newspaper correspondent reported they were presented with a dinner and tea service by local inhabitants, including members of the cricket club. The reporter went on to state "There is a general feeling of regret throughout the district at the Misses Poulett-Harris leaving, as they have always taken a deep interest in the Bay and its institutions and inhabitants, and they carry with them the sincerest wishes of all that they will prosper in the new school life on which they are entering in Hobart."[35]

A violinist,[10] Lily took the music classes at the school. She lived at the school itself, having permanently relocated to the city from Peppermint Bay. However, "when scholastic duties permitted her to visit her home at the Cliffs she was always welcomed by young and old alike" and she continued to play for Oyster Cove. The school initially had ten pupils but, within a few years, grew to have seventy.[34] It was very well regarded throughout its existence.[32][36][37][38]

When she visited her home town, Lily was still actively involved in social[39] and church activities.[40]

She evidently also became a congregant at All Saints in Macquarie Street in South Hobart at this time as well, this church being a relatively short distance from the school.

Personality

[edit]

A fire in October 1896 destroyed most of the Poulett-Harris homestead at Peppermint Bay, including the library.[41] As a result, most of Richard Deodatus Poulett-Harris' papers were lost, including any references to his youngest daughter's life. However, from her obituary and a few other sources, some insights can be gained into her personality.

The obituary states that "Miss Lily was of a mirthful and happy disposition, ever endeavoring to make those with whom she came in contact – and those not a few – cheerful and happy also."[1]

The obituary also contains the following anecdote: "One old man tells how she stopped and obliged by cutting up some tobacco for him, and by many of such little acts and kindnesses, Miss Lily endeared herself to the whole community."[1]

It goes on to quote a member of her cricket team who said that "Fear... was a thing unknown to her."[1]

A memorial plaque dedicated to Lily can be found on the rear wall of All Saints' Anglican Church in South Hobart. Donated by the teachers and students of the Ladies' Grammar School and Kindergarten, it describes Lily as "bright and lovable".

There is also a plaque dedicated to her memory at Saint Simon and Saint Jude Anglican Church in Woodbridge.[42]

Death

[edit]

Lily Poulett-Harris died on the evening of 15 August 1897 at the school's 26 Davey Street address after what her obituary described as "a painful illness".[1] Her death certificate indicates it was tubercular peritonitis.

She was 23 years and eleven months of age. She was buried at 3:00 pm on 17 August 1897 in an Anglican service. Her grave is located at Plot J80, Cornelian Bay Cemetery, Hobart. (Her father and her sister Nellie were later buried in the same plot.)

Legacy

[edit]Although the Oyster Cove Ladies' Cricket Club no longer exists, today Australia has a thriving women's cricket culture, including a national team. Inspired by the success of the Oyster Cove Ladies' Cricket Club and the southern Tasmanian competition, clubs were quickly formed in other parts of Tasmania, such as those at Swansea and Cranbrook on the east coast[43] and Oatlands and York Plains in the midlands.[44]

At the same time as these newer clubs were being created in Tasmania, a Rockhampton Ladies' Club was formed in Queensland. By the end of the 1890s, cricket and rowing two of the most popular competitive sports for women in Australia.[45] Following this, the Victoria Women's Cricket Association was founded in 1905 and the Australian Women's Cricket Association in 1931. The current competition is run by the Women's National Cricket League.

The Ladies' Grammar School and Kindergarten moved to Albuera Street, Battery Point, in 1898 and was run by Nellie Poulett-Harris until her retirement in December 1919,[46] whilst older sister, Anna May,[47] went on to become a relatively well-known actress on the Australian theatre circuit, under the stage name Mary Milward.[48][49] She moved to Melbourne for a time and was trained in Shakespearian performance but eventually settled on light comedies as her area of interest.[50][51][52] She spent her remaining days teaching music and elocution.[53][54] "Vi[olet] always helped Nell in her schools though one pupil's memory was of her often tippling on the sly and her... nephew... thought her distinctly dotty as she grew older!"[42] By 1931, she was working as a governess for four young children.[55] She died on 26 December 1941, at the Albuera Street address[56] whilst Nellie died in the New Norfolk Asylum in July 1935 from arteriosclerosis.[57]

Lily's father, Richard, died on 23 December 1899. A plaque in his honour can be found in Holy Trinity Anglican Church, North Hobart. There is also a memorial fountain in the grounds of the old campus of the University of Tasmania that is dedicated to him.[58] Both Nellie and Richard were buried in the same plot as Lily, whilst Violet was cremated. Lily's other sister, May, also held an editorial position on a Sydney newspaper.[59]

In March 2016, a new article on Lily appeared in Sydney's Daily Telegraph newspaper. Entitled "The Southern Stars owe a huge debt to the Tasmanian schoolteacher who became Australia’s first female cricket star", the article recounts her life and examines her enduring legacy in terms of her ongoing impact on women's cricket in Australia, noting that she has been "responsible for inspiring many other women to take up the sport."[5]

See also

[edit]- Richard Deodatus Poulett-Harris

- Henry Vere Poulett-Harris

- Woodbridge, Tasmania

- Women's cricket

- List of women cricketers

- History of women's cricket

- Women's cricket in Australia

- Cricket in Australia

- Cricket Tasmania

- Women's National Cricket League

- List of Tasmanians

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Woodbridge". The Mercury. Hobart. 27 August 1897. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Family Notices". The Mercury. Hobart. 5 September 1873. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Trinity Church Centenary Celebrations A Heritage". The Mercury. 1 June 1933. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c French, E.L. (1972). "Harris, Richard Deodatus Poulett (1817–1899)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 4. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ a b Lennon, Troy (31 March 2016). "The Southern Stars owe a huge debt to the Tasmanian schoolteacher who became Australia's first female cricket star". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Christmas Examinations. Hutchins School". The Mercury. Hobart. 22 December 1882. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "07 Jun 1884 – The Mercury. Saturday Morning, June 7, 1884". Mercury. 7 June 1884. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Saturday Morning, Dec. 20, 1884". The Mercury. Hobart. 20 December 1884. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "25 Mar 1891 – Oyster Cove". Mercury. 25 March 1891. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Epitome of News". The Mercury. 9 December 1896. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The accident to Mrs. Poulett-Harris". The Mercury. 5 November 1885. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Personal". Zeehan and Dundas Herald. 8 April 1908. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Henry Harris | Australia Cricket | Cricket Players and Officials". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ "Tasmanian Footballers Abroad". The Mercury. 23 May 1888. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Cricket. To-day and Next Saturday". The Mercury. Hobart. 3 December 1910. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "12 Apr 1933 – Obituary Mr. John Murrell. A Former Tasmanian". Mercury. 12 April 1933. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "06 Sep 1882 – Southern Tasmanian Cricket Association". Mercury. 6 September 1882. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "25 Mar 1895 – Ladies' Cricket Match. Heather (Hobart) v. Green". Mercury. 25 March 1895. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ladies' Cricket Match". Mercury. 1 February 1895. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Oyster Cove". Mercury. 14 September 1895. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "The Epitome of News". The Mercury. Hobart. 2 December 1895. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ladies' Cricket Match. Oyster Cove v. North Bruny". The Mercury. Hobart. 8 May 1894. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "09 Jan 1894 – CRICKET. LADIES' CRICKET MATCH. OYSTER COVE V. N". Mercury. 9 January 1894. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Ladies' Cricket Match. Oyster Cove v. Heather". The Mercury. Hobart. 2 January 1895. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ladies' Cricket Match. Oyster Cove v. Atalanta". Mercury. 10 December 1894. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "26 May 1894 – Social Notes (". Australasian. 26 May 1894. Retrieved 9 May 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ladies' Cricket Match. Atalanta v. North Bruny". The Mercury. Hobart. 11 March 1895. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ladies' Cricket Match. Oyster Cove v. Atalanta (". Mercury. 10 December 1894. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "17 Jul 1893 – Advertising". 17 July 1893. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "21 Jul 1890 – Advertising". Mercury. 21 July 1890. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "05 Feb 1894 – The Mercury. Hobart, Monday, Feb. 5, 1894. Epito". Mercury. 5 February 1894. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "School Celebrations. Ladies' Grammar School". The Mercury. Hobart. 19 December 1895. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "School Festivals". Mercury. 19 December 1898. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Ladies' Grammar School and Kindergarten". The Cyclopedia of Tasmania. 1900.

- ^ "18 Dec 1894 – The Mercury. Hobart: Tuesday, DEC. 18, 1894. EPI". Mercury. 18 December 1894. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "School Celebrations. Ladies' Grammar School". Mercury. 24 December 1896. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "16 Dec 1915 – Speech Day. Ladies' Grammar School". Mercury. 16 December 1915. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "19 Dec 1910 – Speech Day. Ladies' Grammar School". Mercury. 19 December 1910. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "10 Apr 1896 – Country News. [From Our Own [?] Woodbridge". Mercury. 10 April 1896. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "10 Apr 1896 – Country News. [From Our Own [?] Woodbridge". Mercury. 10 April 1896. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "31 Oct 1896 – Tasmanian Telegrams. [From Our Own Correspondent". Mercury. 31 October 1896. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Hull 1989, p. 108

- ^ "18 Mar 1896 – Ladies' Cricket Match". Mercury. 18 March 1896. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "12 Apr 1897 – Ladies' Match at Oatlands. Oatlands v. York Plains". Mercury. 12 April 1897. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Howell, Howell & Brown 1989, p. 84

- ^ "22 Dec 1919 – Ladies' Grammar School. Retirement of the Princi". Mercury. 22 December 1919. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ladies' Corner – Social Items". Trove. 20 May 1905. p. 3. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "02 Oct 1906 – Music and Drama". Mercury. 2 October 1906. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "23 Oct 1906 – Amusements Theatre Royal. "Quality-Street."". Mercury. 23 October 1906. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "15 Apr 1919 – Music and Drama". Mercury. 15 April 1919. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "10 Oct 1918 – Amusements. Strand Movies". Mercury. 10 October 1918. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Marchant Concert". The Mercury. Hobart. 13 January 1909. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Music and Drama". The Mercury. Hobart. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "26 Feb 1926 – Letters to the Editor. Irrigation in Tasmania. t". Mercury. 26 February 1926. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "31 Aug 1931 – Historical Exhibition "Old Time" Pageant Quaint". Mercury. 31 August 1931. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "29 Dec 1941 – Family Notices". Mercury. 29 December 1941. Retrieved 11 June 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "23 Jul 1935 – Obituary The Rev. E. H. Sugden Prominent Literar". Mercury. 23 July 1935. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Late Rev. Poulett-Harris". The Examiner. Launceston. 1 August 1900. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Anstice (13 May 1936). "The Social Round Welcomes and Farewells Hobart Party Gatherings". The Mercury. Hobart. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

Bibliography

[edit]- Howell, Max; Howell, Reet; Brown, David W. (1989). The Sporting Image, A pictorial history of Queenslanders at play. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0-7022-2206-2.

- Hull, Peggy (1989). The Ark That Binds: Being the Ancestry of the Children of Henry Vere Seymour Gaynor and Florence Lilian Gaynor Back Four Generations. Epping: P. Hull. ISBN 073165515X.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch