Chilean Central Valley

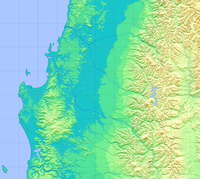

The Central Valley (Spanish: Valle Central), Intermediate Depression, or Longitudinal Valley is the depression between the Chilean Coastal Range and the Andes Mountains. The Chilean Central Valley extends from the border with Peru[A] to Puerto Montt in southern Chile, with a notable interruption at Norte Chico (27°20'–33°00' S). South of Puerto Montt the valley has a continuation as a series of marine basins up to the isthmus of Ofqui. Some of Chile's most populous cities lie within the valley including Santiago, Temuco, Rancagua, Talca and Chillán.

Northern section (18°30'–27°20' S)

[edit]

In northernmost Chile the central valley is made up of the Pampitas,[B] a series of small flats dissected by deep valleys.[2] Immediately south of the Pampitas, in Tarapacá Region and northern of Antofagasta Region, the Central Valley is known as Pampa del Tamarugal.[3][4] Contrary to the Pampitas valleys descending from the Andes do not incise the plains but merge into the surface of Pampa del Tamarugal at a height of c. 1500 m.[3] The westernmost portion of Pampa del Tamarugal has a height of 600 m. This western part contain a series of raised areas called pampas and basins containing salt flats.[3] Interconnecting basins are important corridors for communication and transport in northern Chile.[5]

South of Loa River the valley continues, flanked by Cordillera Domeyko to east, until it is ends at the latitude of Taltal (25°17' S). It re-appears around Chañaral (26°20' S) as an isolated basin surrounded by mountains and hills.[4][6] This 250 km long and up to 70 km wide basin is called Pampa Ondulada or Pampa Austral.[7] As the Pampa Ondulada is extinguished at Copiapó River (27°20' S)[7] in the Norte Chico region running south of this river there is no proper Central Valley, only a few narrow north–south depressions that align with geological faults.[8]

In the northern section of the central valley vegetation is extremely scarce as result of conditions of extreme aridity in Atacama Desert. Only to the south in Atacama Region does a Chilean Matorral vegetation exist. The northern portion of the matorral is made up by the Nolana leptophylla–Cistanthe salsoloides association while the southern half by the Skytanthus acutus–Atriplex deserticola association.[9][10]

Central section (33°00'–41°30' S)

[edit]

The main portion the Central Valley extends from Tiltil (33°05' S) near Santiago to Temuco (38°45' S).[11][12] The Coast Range and the Andes almost merge in two locations: one between Santiago and Rancagua and another between San Fernando and Rengo.[11] The result is the enclosure of the Central Valley into two smaller basins in the north: Santiago Basin and Rancagua Basin.[13][14]

The valley runs an un-interrupted length of 360 km from Angostura de Pelequén in the north to Bío Bío River (37°40' S) in the south.[14] It broadens from 12 km at Molina (35°05' S) in the north to 74 km in the south at Laja (37°15' S) the relief being gently undulating.[14] Conglomerate of Andean provenance cover large swathes of the Central Valley being less common to the west near the Coast Range. Occasionally the valley contains isolated hills and mountains made up of basement rocks.[11] At the latitudes of Temuco the Coast Range is subdued to such degree the Central Valley coalesces with the coastal plains.[15]

In the 110 km between Gorbea and Paillaco (c. 39–40° S) the Central Valley is inexistent as the region is instead crossed by a series of east–west mountainous ridges and broad fluvial valleys.[15][12] South of this region the Central Valley re-appears in the south to extend into Osorno and Puerto Montt (41°30' S).[12] This southern section is 190 km long from north to south.[15] The Central Valley south of Bío Bío River has been influenced by volcanism and past glaciations giving origin to the ñadis and moraines that cover parts of the valley.[16]

The natural vegetation of the central section vary from north to south. To a lesser degree vegetation also vary towards the foothills of the Andes and the Chilean Coastal Range. From Santiago to Linares thorny woodlands of Acacia caven are dominant.[17] In Ñuble Region two sclerophyll vegetation types cover the territory. These are the associations of Lithrea caustica–Peumus boldus and Quillaja saponiana–Fabiana imbricata.[18] From Bío Bío River to the south Nothofagus obliqua becomes the dominant tree species.[19][20] Only Llanquihue Lake and the Puerto Montt area are exceptions to this being respectively dominated by Nothofagus dombeyi–Eucryphia cordifolia and Nothofagus nitida–Podocarpus nubigena.[21][22]

Southern marine basins (41°30'–46°50' S)

[edit]

South of Puerto Montt the continuation of the Central Valley is made up of a series of marine basins including Reloncaví Sound, Gulf of Ancud, and the Gulf of Corcovado that separates Chiloé Island from the mainland.[23][12] Further south the valley runs as the narrow Moraleda Channel. Emerged portions include numerous small islands plus the eastern coast of Chiloé Island and Taitao Peninsula east of Presidente Ríos Lake, including the Isthmus of Ofqui. (46°50' S).[23]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In fact the valley extends into southern Peru where it receives the name of Llanuras Costeras.[1]

- ^ Geographer Humberto Fuenzalida introduced the concept of the Pampitas in 1950.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Evenstar, L.A.; Mather, A.E.; Hartley, A.J.; Stuart, F.M.; Sparks, R.S.J.; Cooper, F.J. (2018). "Geomorphology on geologic timescales: Evolution of the late Cenozoic Pacific paleosurface in Northern Chile and Southern Peru" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 171: 1–27. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.04.004. hdl:2164/10306. S2CID 53974870.

- ^ a b Börger, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Börger, p. 41.

- ^ a b Brüggen, p. 6.

- ^ Börger, p. 42.

- ^ Börger, p. 43.

- ^ a b Börger, p. 47.

- ^ Brüggen, p. 5.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b c Brüggen, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Brüggen, p. 2.

- ^ Börger, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Börger, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Börger, p. 122.

- ^ Börger, p. 123.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 130–133.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 144–147.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 183–186.

- ^ Luebert & Pliscoff, pp. 198–200.

- ^ a b Börger, p. 137.

External links

[edit]- An aerial Google view of the Chilean Central Valley. Argentina lies to the east of the Andes range

- Chilean National Tourism Service (in Spanish)

- Chilean Meteorological Service (in Spanish)

- Bibliography

- Börger Olivares, Reinaldo (1983). Geografía de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. Tomo II: Geomorfología. Instituto Geográfico Militar.

- Brüggen, Juan (1950). Fundamentos de la geología de Chile (in Spanish). Instituto Geográfico Militar.

- Luebert, Federico; Pliscoff, Patricio (2017) [2006]. Sinopsis bioclimática y vegetacional de Chile (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria. p. 381. ISBN 978-956-11-2575-9.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch