Master of Animals

The Master of Animals, Lord of Animals, or Mistress of the Animals is a motif in ancient art showing a human between and grasping two confronted animals.[1] The motif is very widespread in the art of the Ancient Near East and Egypt. The figure may be female or male, it may be a column or a symbol, the animals may be realistic or fantastical, and the human figure may have animal elements such as horns, an animal upper body, an animal lower body, legs, or cloven feet. Although what the motif represented to the cultures that created the works probably varies greatly, unless shown with specific divine attributes, when male the figure is typically described as a hero by interpreters.[2]

The motif is so widespread and visually effective that many depictions probably were conceived as decoration with only a vague meaning attached to them.[3] The Master of Animals is the "favorite motif of Achaemenian official seals", but the figures in these cases should be understood as the king.[4]

The human figure may be standing, as found from the fourth millennium BC, or as kneeling on one knee found from the third millennium BC. They are usually shown looking frontally, but in Assyrian pieces typically they are shown from the side. Sometimes the animals are clearly alive, whether fairly passive and tamed, or still struggling, rampant, or attacking. In other pieces they may represent dead hunter's prey.[5]

Other associated representations show a figure controlling or "taming" a single animal, usually to the right of the figure. But the many representations of heroes or kings killing an animal are distinguished from these.[6]

Art

[edit]

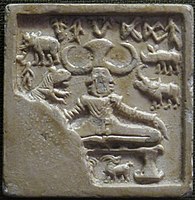

The earliest known depiction of such a motif appears on stamp seals of the Ubaid period in Mesopotamia.[8] The motif appears on a terracotta stamp seal from Tell Telloh, ancient Girsu, at the end of the prehistoric Ubaid period of Mesopotamia, c. 4000 BC.[9][10][11]

The motif also was given the topmost location of the famous Gebel el-Arak Knife in the Louvre, an ivory and flint knife dating from the Naqada II d period of Egyptian prehistory, which began c. 3450 BC. Here a figure in Mesopotamian dress, often interpreted to be a god, grapples with two lions. It has been connected to the famous Pashupati seal from the Indus Valley civilization (2500-1500 BC), showing a figure seated in a yoga-like posture, with a horned headress (or horns), and surrounded by animals.[12]

This in turn is related to a figure on the Gundestrup cauldron, who sits with legs part-crossed, has antlers, is surrounded by animals, and grasps a snake in one hand and a torc in the other. This famous and puzzling object probably dates to 200 BC, or possibly as late as 300 AD, and although found in Denmark, it may have been made in Thrace.

A form of the motif appears on a belt buckle of the Early Middle Ages from Kanton Wallis, Switzerland, which depicts the biblical figure of Daniel between two lions.[13]

The purse-lid from the Sutton Hoo burial of about 620 AD has two plaques with a human between two wolves, and the motif is common in Anglo-Saxon art and related Early Medieval styles, where the animals generally remain aggressive. Other notable examples of the motif in Germanic art include one of the Torslunda plates, and helmets from Vendel and Valsgärde.[14]

In the art of Mesopotamia the motif appears very early, usually with a "naked hero", for example at Uruk in the Uruk period (c. 4000 to 3100 BC), but was "outmoded in Mesopotamia by the seventh century BC".[15] In Luristan bronzes the motif is extremely common, and often highly stylized.[16] In terms of its composition this motif compares with another very common motif in the art of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean, that of two confronted animals flanking and grazing on a Tree of Life, interpreted as representing an earth deity.

- Master of animals, Susa I (4200-3800 BC), Louvre Museum

- Terracotta stamp seal with Master of Animals motif, Tell Telloh, ancient Girsu, End of Ubaid period, c. 4000 BC [17][18]

- Gebel el-Arak Knife ivory handle (front), after c. 3450 BC

- Soapstone stamp with, depicting an ibex-headed character taming snakes. Lorestan, 4th millennium BC. Louvre Museum

- Protective Master from the harp found at Ur, dated circa 2600 BCE

- Chlorite, Jiroft culture Iran, ca. 2500 BC, Bronze Age I a cloven-footed human flanked by scorpions and lionesses

- Luristan bronze finial in the form of the 'Master of Animals'

- Achaemenid seal impression with the Persian king subduing two Mesopotamian lamassu

- Iranian Master of Animals with two snakes

- Impression from the Pashupati seal, Indus Valley civilization

- One of the Minoan snake goddess figurines, about 1600 BC

- Detail of the Gundestrup Cauldron antlered figure

- Confronted animals, here ibexes flank a Tree of Life, from Sasanian Iran (fifth or sixth-century AD) (Cincinnati Art Museum)

- Luristan bronze horse bit cheekpiece with "Master of Animals" motif, about 700 BC

Deity figures

[edit]

Although such figures are not all, or even usually, deities, the term may be a generic name for a number of deities from a variety of cultures with close relationships to the animal kingdom or in part animal form (in cultures where that is not the norm). These figures control animals, usually wild ones, and are responsible for their continued reproduction and availability for hunters.[21] They sometimes also have female equivalents, the so-called Mistress of the Animals.[22]

Many Mesopotamian examples may represent Enkidu, a central figure in the Ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh. They all may have a Stone Age precursor who was probably a hunter's deity. Many relate to the horned deity of the hunt, another common type, typified by Cernunnos, and a variety of stag, bull, ram, and goat deities. Horned deities are not universal however, and in some cultures bear deities, such as Arktos, might take the role, or even the more anthropomorphic deities who lead the Wild Hunt. Such figures are also often referred to as 'Lord of the forest' or 'Lord of the mountain'.

The Greek god shown as "Master of Animals" is usually Apollo as a hunting deity.[23] Shiva has the epithet Pashupati meaning the "Lord of animals", and these figures may derive from an archetype.[24] Chapter 39 of the Book of Job has been interpreted as an assertion of the deity of the Hebrew Bible as Master of Animals.[25]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Arruz, 303-304

- ^ Ross, Micah (ed), From the Banks of the Euphrates: Studies in Honor of Alice Louise Slotsky, pp. 174-177, 2008, Eisenbrauns, ISBN 1575061449, 9781575061443, Google books

- ^ Frankfort, 75

- ^ Teissier, Beatrice, Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals from the Marcopolic Collection, p. 46, 1984, University of California Press, ISBN 0520049276, 9780520049277, google books

- ^ "Horse Cheekpiece" by "OWM", in Notable Acquisitions, 1980-1981, pp. 7-8, 1981, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0870992848, 9780870992841, google books

- ^ Arruz, 308

- ^ "Stamp-seal British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Charvát, Petr (2003). Mesopotamia Before History. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 9781134530779.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 304. ISBN 9781614510352.

- ^ Charvát, Petr (2003). Mesopotamia Before History. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 9781134530779.

- ^ Werness, 270

- ^ Gaimster, Marit. 1998. Vendel period bracteates on Gotland.

- ^ Gaimster, Marit. 1998. Vendel period bracteates on Gotland

- ^ Frankfort, 30-31 (Uruk), 75, 78-79, 347 (2nd quote)

- ^ Frankfort, 343-347

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 304. ISBN 9781614510352.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 146. ISBN 9780759116429.

- ^ Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand (1975). An Introduction to the Study of Indian History. Popular Prakashan. p. 64. ISBN 9788171540389.

- ^ Garfinkel

- ^ Arruz, 303-304

- ^ Arruz, 303-304, 308

- ^ Werness, 270

- ^ Doak, Brian R., Consider Leviathan: Narratives of Nature and the Self in Job, 2014, Fortress Press, ISBN 145148951X, 9781451489514, google books; Job:39, NIV

References

[edit]- Aruz, Joan, et al., Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age, 2014, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0300208081, 9780300208085, google books

- Frankfort, Henri, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, Pelican History of Art, 4th ed 1970, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561072

- Garfinkel, Alan P., Donald R. Austin, David Earle, and Harold Williams, 2009, "Myth, Ritual and Rock Art: Coso Decorated Animal-Humans and the Animal Master". Rock Art Research 26(2):179-197. Section "The Animal Master", The Journal of the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA) and of the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO)]

- Werness, Hope B., Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in World Art, 2006, A&C Black, ISBN 0826419135, 9780826419132, google books

Further reading

[edit]- Hinks, Roger (1938). The Master of Animals, Journal of the Warburg Institute, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Apr., 1938), pp. 263–265

- Chittenden, Jacqueline (1947). The Master of Animals, Hesperia, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1947), pp. 89–114

- Slotten, Ralph L. (1965). The Master of Animals: A study in the symbolism of ultimacy in primitive religion, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 1965, XXXIII(4): 293-302

- Bernhard Lang (2002). The Hebrew God: Portrait of an Ancient Deity, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 75–108

- Yamada, Hitoshi (2013). "The "Master of Animals" Concept of the Ainu", Cosmos: The Journal of the Traditional Cosmology Society, 29: 127–140

- Garfinkel, Alan P. and Steve Waller, 2012, Sounds and Symbolism from the Netherworld: Acoustic Archaeology at the Animal Master’s Portal. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 46(4):37-60

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch

![Terracotta stamp seal with Master of Animals motif, Tell Telloh, ancient Girsu, End of Ubaid period, c. 4000 BC [17][18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Stamp_seal_with_Master_of_Animals_motif%2C_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_End_of_Ubaid_period%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO14165_%28detail%29.jpg/193px-Stamp_seal_with_Master_of_Animals_motif%2C_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_End_of_Ubaid_period%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO14165_%28detail%29.jpg)

![Indus valley civilization seal, with human flanked by two lions (2500–1500 BC).[19][20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1e/Indus_valley_civilization_%22Gilgamesh%22_seal_%282500-1500_BC%29.jpg/200px-Indus_valley_civilization_%22Gilgamesh%22_seal_%282500-1500_BC%29.jpg)