Kern River

| Kern River Río de San Felipe, La Porciúncula, Po-sun-co-la, Porsiuncula River[1] | |

|---|---|

Panorama of the upper Kern River | |

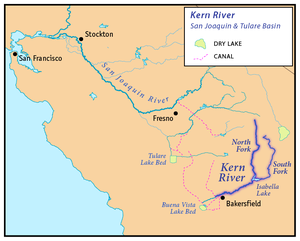

Map of the San Joaquin and Tulare Basin region with the Kern River highlighted. Some rivers shown are intermittent or normally dry. A few selected canals are shown. Below: Map of the San Joaquin and Tulare Basin region showing the old lakes and river courses. | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Sierra Nevada, San Joaquin Valley |

| District | Tulare County, Kern County |

| City | Bakersfield |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Kings-Kern Divide |

| • location | Sequoia National Park |

| • coordinates | 36°41′48″N 118°23′53″W / 36.69667°N 118.39806°W[2] |

| • elevation | 13,608 ft (4,148 m)[3] |

| Mouth | Buena Vista Lake Bed |

• location | San Joaquin Valley |

• coordinates | 35°16′4″N 119°18′25″W / 35.26778°N 119.30694°W[2] |

• elevation | 299 ft (91 m)[2] |

| Length | 164 mi (264 km)[2] |

| Basin size | 3,612 sq mi (9,360 km2)[4] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Near Democrat Springs, CA[5] |

| • average | 946 cu ft/s (26.8 m3/s)[5] |

| • minimum | 10 cu ft/s (0.28 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 47,000 cu ft/s (1,300 m3/s) |

| Type | Wild, Scenic, Recreational |

| Designated | November 24, 1987 |

The Kern River is an Endangered, Wild and Scenic river in the U.S. state of California, approximately 165 miles (270 km) long. It drains an area of the southern Sierra Nevada mountains northeast of Bakersfield. Fed by snowmelt near Mount Whitney, the river passes through scenic canyons in the mountains and is a popular destination for whitewater rafting and kayaking. It is the southernmost major river system in the Sierra Nevada, and is the only major river in the Sierra that drains in a southerly direction.

The Kern River formerly emptied into the now dry Buena Vista Lake and Kern Lake via the Kern River Slough, and Kern Lake in turn emptied into Buena Vista Lake via the Connecting Slough at the southern end of the Central Valley. Buena Vista Lake, when overflowing, first backed up into Kern Lake and then upon rising higher drained into Tulare Lake via Buena Vista Slough and a changing series of sloughs of the Kern River. The lakes were part of a partially endorheic basin that sometimes overflowed into the San Joaquin River.[6] This basin also included the Kaweah and Tule Rivers, as well as southern distributaries of the Kings River that all flowed into Tulare Lake.

Since the late 19th century the Kern has been almost entirely diverted for irrigation, recharging aquifers, and the California Aqueduct, although some water empties into Lake Webb and Lake Evans, two small lakes in a portion of the former Buena Vista lakebed. The lakes were created in 1973 for recreational use. The lakes hold 6,800 acre⋅ft (8,400 dam3) combined.[7] Crops are grown in the rest of the former lakebed. In extremely wet years the river will reach the Tulare Lake basin through a series of sloughs and flood channels.

Despite its remote source, nearly all of the river is publicly accessible. The Kern River is particularly popular for wilderness hiking and whitewater rafting. The Upper Kern River is paralleled by trails to within a half-mile of its source (which lies at 13,600 feet (4,100 m)). Even with the presence of Lake Isabella, the river is perennial down to the lower Tulare Basin. Its swift flow at low elevation makes the river below the reservoir a popular location for rafting.

Course

[edit]The Kern begins in the Sierra Nevada in Sequoia National Park in northeastern Tulare County, near the border with Inyo County.[8] The main branch of the river (sometimes called the North Fork Kern River) rises from several small lakes in a basin northwest of Mount Whitney. The headwaters are surrounded by the Great Western Divide to the west, the Kings-Kern Divide to the north and the main Sierra Crest to the east, all of which have multiple peaks above 13,000 feet (4,000 m).[8] The Kern River flows due south through a deep glacier-carved valley, passing through Inyo and Sequoia National Forests and the Golden Trout Wilderness, and receiving numerous tributaries including Rock Creek, Big Arroyo, Golden Trout Creek and Rattlesnake Creek.[9][10][11] After deviating briefly from its due south course as it flows east around Hockett Peak, it is joined by the Little Kern River from the northwest at a site called Forks of the Kern.[12] Below there, the Kern River continues south, and is joined by more tributaries including Peppermint Creek, South Creek, Brush Creek, and Salmon Creek, which all form large waterfalls as they tumble into the Kern River canyon.[13][14][15]

At Kernville the river emerges from its narrow canyon into a wide valley where it is impounded in Lake Isabella, formed by Isabella Dam.[16] The area was once known as Whiskey Flat, the former location of the town of Kernville. In Lake Isabella, it is joined by its largest tributary, the South Fork Kern River, which drains a high plateau area to the east of the North Fork drainage.[17] The 95-mile (153 km)-long South Fork rises in Tulare County and flows south through Inyo National Forest, turning west after entering Kern County.[18][19]

Below Isabella Dam the Kern River flows southwest in a rugged canyon along the south edge of the Greenhorn Mountains, parallel to SR 178. A number of hot springs (Scovern, Miracle, Remington, Delonegha, Democrat) are located along this section of the river.[20] With a descent of 2,000 feet (610 m) between Isabella Dam and Bakersfield, this section of the Kern River feeds several hydroelectric plants and is also a popular whitewater run. Due to upstream dam releases for irrigation and power generation, this part of the river has a swift flow even in the driest summers.[21] The river then flows through a winding valley in the Sierra foothills[22] before entering the San Joaquin Valley at Bakersfield, the largest city on the river.[23] In Bakersfield proper, most of the river's flow is diverted into various canals for agricultural use in the southern San Joaquin Valley, and provide municipal water supplies to the City of Bakersfield and surrounding areas. Diverting the river's flow has left 30 miles (48 km) of the riverbed that runs through Bakersfield dry.[24] This fertile region is a large alluvial plain, or inland delta, formed by the Kern River, which once spread out into vast wetlands and seasonal lakes.

The Friant-Kern Canal, constructed as part of the Central Valley Project, joins the Kern about 4 mi (6.4 km) west of downtown Bakersfield, restoring some flow to the river. The river channel continues about 20 miles (32 km) southwest to a point near the California Aqueduct on the western side of the San Joaquin Valley. A weir allows excess floodwaters from the Kern to drain into the California Aqueduct, while any remaining water continues south into the seasonal Buena Vista Lake, which once reached sizes of about 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) in wet periods. Historically, a 20 mi (32 km) distributary of the Kern split off above Bakersfield and flowed south to what is now Arvin, where it formed the seasonal Kern Lake, which would grow to cover about 8,300 acres (3,400 ha) during wet periods. Water from Kern Lake would then flow west through Buena Vista Slough into Buena Vista Lake.

In periods of extremely high runoff, Buena Vista Lake overflowed and joined other wetlands and seasonal lakes in a series of sloughs that drained north into the former Tulare Lake, which would sometimes overflow into the San Joaquin River via Fresno Slough.[25]

The Kern River is one of the very few rivers in the Central Valley which does not contribute water to the Central Valley Project (CVP). However, water from the CVP, mainly the Friant-Kern Canal, will be deposited for water storage in the aquifers.

History

[edit]

The river was named by John C. Frémont in honor of Edward M. Kern in 1845 who, as the story goes, nearly drowned in the turbulent waters.[26] Kern was the topographer of Fremont's third expedition through the American West. Before this, the Kern River was known as the Río de San Felipe as named by Spanish missionary explorer Francisco Garcés when he explored the Bakersfield area on May 1, 1776. On August 2, 1806, Padre Zavidea renamed the river La Porciúncula for the day of the Porciuncula Indulgence. It was locally known as Po-sun-co-la until its renaming by Fremont.[1]

Gold was discovered along the upper river in 1853. The snowmelt that fed the river resulted in periodic torrential flooding in Bakersfield until the construction of the Isabella Dam in the 1950s. These floods would periodically change the channel of the river. Since the establishment of Kern County in 1866 the main channel has flowed through what is the main part of downtown Bakersfield along Truxtun Avenue and again made a south turn along what is Old River Road. Many of the irrigation canals that flow in a southerly direction from the river follow the old channels of the Kern River, especially the canal that flows along Old River Road. The irrigated region of the Central Valley near the river supports the cultivation of alfalfa, carrots, fruit, and cotton, cattle grazing, and many other year-round crops. In 1987 the United States Congress designated 151 miles (243 km) of the Kern's North (Main) Fork and South Fork as a National Wild and Scenic River.

The Great 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake on January 9, 1857, with an estimated magnitude of 7.9 on the San Andreas Fault was strong enough to temporarily switch the direction of the flow of the Kern River. Fish in the now dry Tulare Lake were left stranded on the shores.[27]

The Buena Vista Lake basin is an arid area and the Kern River is the only significant water supply. Ongoing conflicts between urban and agricultural interests complicate management decisions, in recent years owing to the expiration of some long-term contractual agreements.[28]

Lux v. Haggin - 1886 California Supreme Court case on water rights

[edit]The Kern River was at the center of Lux v. Haggin, 69 Cal. 255; 10 P. 674; (1886), a historic case in the development of water rights in California, and also one of the most consequential water lawsuits in American history.

The overarching issue in Lux v. Haggin was whether the court would uphold English common law riparian rights (even though they were poorly suited to California's Mediterranean climate), institute the primacy of appropriative water rights, or create an entirely new system of water rights. The decision was important because it gave the court a chance to either continue to uphold English common law and riparian rights or give appropriative rights supremacy.

In the end, the court recognized both water rights systems but decided that appropriative rights were secondary to riparian rights. The ruling "created chaos by shackling the state with two fundamentally incompatible water allocation systems".

Additionally, the original definition of "reasonable" water use under English common law was changed. The court decided that water could be used for commercial and agricultural purposes as long as the use did not negatively affect other riparian landowners. This broadening of the "reasonable" use definition meant that riparian landowners could now use more water than previously allowed.

The subsequent 1888 Miller-Haggin Agreement that divides the water between First Point and Second Point users, still governs the use of Kern River water today.

National Wild And Scenic Rivers System designation

[edit]On November 24, 1987, portions of the Kern River were designated as Wild & Scenic under the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act. The Wild & Scenic designation covers 151.0 miles (243.0 km) broken down as Wild — 123.1 miles (198.1 km); Scenic — 7.0 miles (11.3 km); Recreational — 20.9 miles (33.6 km).[29]

Ecology

[edit]The Kern River watershed is the native range of California's State Freshwater Fish, California golden trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita), which are native to the Kern River tributaries South Fork Kern River and Golden Trout Creek,[30] and the latter's tributary, Volcano Creek.[31] Two currently recognized and closely related sibling subspecies. The Little Kern golden trout (O. m. whitei), found in the Little Kern River basin, and the Kern River rainbow trout (O. m. gilberti), are also found in the Kern River system. Together, these three trout form what is sometimes referred to as the "Golden Trout Complex".[32]

The rare and endangered Kern Canyon slender salamander lives alongside the river.[33]

In 2008, after public outcry, the City of Bakersfield and the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) decided to relocate a family of California Golden beaver (Castor canadensis subauratus) instead of killing them.[34] California Golden beaver were native to the Central Valley and throughout the Sierra Nevada. Specifically to the Kern watershed, an oral history was taken from Roy De Voe, who claimed to have seen "very old beaver sign" on the east side of the Kern River at Funston Meadow (elevation 6,476 feet (1,974 m))[35] in 1946. Also, Mr. De Voe reported that his friend Kenny Keelor trapped the Kern River for beaver around 1900, making his camp at the mouth of Rattlesnake Creek (elevation 6,585 feet (2,007 m))[36] until they were trapped out completely by 1910 – 1914.[37] The presence of Beaver Canyon Creek, tributary to the lower Kern River just east of Delonegha Hot Springs, is also consistent with the Kern River watershed having historically supported native beaver.[38] This oral history is consistent with another oral history taken one watershed to the north by CDFG's Donald T. Tappe from a retired game warden in 1940, who stated that beaver were "apparently not uncommon on the upper part of the Kings River" until 1882–1883.[39] Currently, there are large numbers of beaver in the Ramshaw Meadows on the South Fork Kern River where their dams are trapping sediment, forming extensive pools, accelerating meadow restoration, and increasing riparian willow habitat.[31][40]

The Panorama Vista Preserve

[edit]Panorama Vista Preserve[41] is a 930-acre wildlife refuge and outdoor recreational area located in the northeast part of Bakersfield, California. The preserve includes hiking trails, biking paths, and areas for horseback riding, and is known for being dog-friendly. It serves as a sanctuary for endangered species such as the San Joaquin Kit Fox and the Bakersfield Cactus. Panorama Vista Preserve is located near Panorama Park and "The Bluffs" and comprises two distinct floodplain elevations that support different vegetation communities. The lower terrace features typical riparian forests and shrub lands, while the upper terrace supports a salt-brush scrub community and relict stands of the endangered Bakersfield Cactus. Visitors to the preserve can see the Gordon's Ferry historic landmark and learn about the natural and cultural history of the region.

Kern River Hatchery

[edit]Just north of Lake Isabella is the Kern River Hatchery. The Kern River Hatchery is also home to the Fishing and Natural History Museum, features picnic grounds and outdoor activities in the area.[42]

Hatchery closure

[edit]On December 1, 2020, after 3 years of extensive renovations, the hatchery was closed down by California Department of Fish and Wildlife, just 20 months after being reopened.[43] According to CDFW, the hatchery is closed for repairs with the primary focus on "replacement of a pipeline that is more than 50 years old and no longer adequately provides a reliable water supply for fish production".[44] There is currently no date set for reopening the hatchery. Despite the closure of the hatchery, the hatchery still diverts 35 cfs year-round[45] from the North Fork Kern River at the expense of North Fork Kern fishery and its biome.[46]

Geology

[edit]

The upper Kern River Canyon was created primarily as a result of tectonic forces, and not just by the erosional force of the river. The geologically active Kern Canyon Fault runs the length of the canyon, from the river's headwaters down to the Walker Basin about 10 miles (16 km) south of Lake Isabella. The river's course has been modified several times throughout ancient geological history. Prior to 10 million years ago, the Kern River flowed into the San Joaquin Valley at a point further south, along what is now Walker Basin Creek, which outlets north of Arvin. Uplift west of the Kern Canyon Fault blocked the river and forced it to cut a new course further north, forming the steep gorge below Lake Isabella and Bakersfield.[47] The upper part of the Kern River canyon, at least above Golden Trout Creek, was widened and deepened by glaciers during the Ice Ages.[48] The Kern Canyon fault passes very close to Isabella Dam, and is considered a threat to the dam's structural stability.[49]

The Kern River Oil Field is adjacent to the river on the north, just before the river flows into Bakersfield. The large oil field, on low hills which rise gradually into the Sierra foothills, formerly allowed much of its wastewater to drain directly south into the river. However, modern environmental regulation ended this practice, and the contaminated water is now cleaned at water treatment plants and used to irrigate farms in the valley to the west.[50]

Discharge

[edit]

Due to water diversion and Isabella Dam the Kern River's discharge changes considerably over its length. The highest mean annual flows occur just downriver of Isabella Dam, but because the dam serves to regulate the flow of water the highest daily discharges occur above the dam on the North Fork section of the Kern River. The USGS stream gauge on the North Fork Kern River has recorded an average annual mean discharge of 806 cubic feet per second (23 m3/s) and a maximum daily discharge of 33,600 cu ft/s (950 m3/s), and the gauge on the South Fork Kern River shows an average annual mean discharge of 123 cu ft/s (3.5 m3/s) and a maximum daily discharge of 14,000 cu ft/s (400 m3/s). In contrast the first stream gauge below Isabella Dam has recorded an average annual mean of 946 cu ft/s (27 m3/s) but a maximum daily discharge of only 7,030 cu ft/s (200 m3/s). Due to water withdrawals the three stream gauge stations below Isabella Dam show a dramatically decreasing discharge. At the last gauge, near Bakersfield, the river's average flow is only 312 cu ft/s (8.8 m3/s).[5]

Recreation and Tourism

[edit]

Activities

[edit]Kern Canyon, the deep canyon of the river northeast of Bakersfield, is a popular location for fishing and boating, particularly fly fishing and whitewater rafting, whitewater kayaking, and riverboarding. Of particular interest to fishermen are the Kern River rainbow trout, the Little Kern golden trout, and the California golden trout. The Kern Canyon is popular for camping,[51] hiking, and picnicking. There are developed campgrounds maintained by the US Forest Service along the North Fork of the Kern River. Campgrounds include Camp 3, Fairview, Goldledge, Headquarters, Hospital Flat, and Limestone. All of the campgrounds are open in the summer months while only a few remain open year-round.

Safety Concerns

[edit]The Kern is well known for its danger, and is sometimes referred to as the "killer Kern". A sign at the mouth of Kern Canyon warns visitors: "Danger. Stay Out. Stay Alive" and tallies the deaths since 1968; as of May 23, 2024, the number of deaths listed is 335.[52] Merle Haggard's song "Kern River" fictionally recounts such a tragedy.

Below the canyon the Kern River has a gradient of 0.3% until it reaches the Kern River Oil Field and begins to meander along flat land into and through the city of Bakersfield. Tubing is popular along this stretch.

Kernville Whitewater

[edit]The Class II whitewater located in Kernville is used for the slalom event of the annual Kern River Festival.

The Kern River Parkway Trail

[edit]The Kern River Parkway Trail is a system of hiking and biking trails that extends along the Kern River from the mouth of the canyon to Hart Park in Bakersfield, California. The trail system is part of the larger Kern River Parkway, which includes several parks, picnic areas, and green spaces along the river.

History

[edit]The Kern River Parkway Trail was first proposed in the 1970s as part of a plan to create a system of parks and trails along the Kern River. The first section of the trail, between the mouth of the canyon and Buena Vista Lake, was completed in the 1980s. Since then, the trail has been extended to its current length, with several amenities added along the way.

Route

[edit]The Kern River Parkway Trail is a multi-use trail that can be used for hiking, biking, and equestrian activities. The trail extends for approximately 30 miles, from the mouth of the canyon to Hart Park in Bakersfield.

The trail follows the Kern River through several parks and green spaces, including the Kern River County Park, Yokuts Park, and the Kern River Preserve. The trail is mostly flat, with a few gentle slopes and curves, and several rest stops and picnic areas are available along the way.

Amenities

[edit]The Kern River Parkway Trail offers several amenities for hikers, bikers, and equestrians, including parking areas, restrooms, and drinking fountains. The trail system includes several hiking and biking trails that branch off from the main trail. These trails offer a variety of terrain and difficulty levels, from easy walks along the river to challenging mountain bike rides through the surrounding hills. The trail is maintained by the City of Bakersfield and the Kern County Parks and Recreation Department, with funding provided by grants and community donations.

In popular culture

[edit]Songs

[edit]Kern River - 1985 song written by American country music singer Merle Haggard.

Kern River - 2022 song written by American Comedian and Songwriter Tim Heidecker in his album High School (2022).

Kern River Blues - Also written by Merle Haggard, this was his last recording.[53]

Art Projects

[edit]

Flow

[edit]Flow was a temporary art installation created by environmental artist Andres Amador on the Kern River in Bakersfield, California. The installation was meant to highlight the irony of the dry riverbed and raise awareness about the need to restore water flow to the Kern River. It was commissioned by "Bring Back the Kern",[54] a community group advocating for the restoration of the river, and supported by the Virginia and Alfred Harrell Foundation.

The installation featured a 2,500-square-foot image on the riverbed floor south of the 24th street overcrossing, created with an invasive bamboo-like reed called Arundo, which the group would like to eradicate from the Kern River. The design evoked the smooth lines of flowing water and the eddies created by a river's currents. The lines in the design were over 2500 feet in length, making it a large-scale installation.

Flow involved extensive community involvement, including volunteer participation in the collection of plant material, the creation of the installation, and the removal of the artwork. The plant material used in the installation was collected by volunteers who had removed invasive plants from elsewhere along the parkway. The seeds from this plant were sterile, but the plant material was removed and disposed of within two weeks of the installation to ensure that the invasive weeds did not spread elsewhere along the river.

Bring Back the Kern hoped to draw attention to the lack of water in the Kern River and advocate for solutions, including calling upon the State Water Resources Control Board to award unappropriated water to the city of Bakersfield. The group believed that restoring water flow to the river would revive the local ecosystem, provide recreation opportunities, and enhance property values in the city.

Flow was a visual representation of the group's message, highlighting the need for action to restore the Kern River. The installation was open to the public from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Thursday, February 11, and was available for viewing until its removal two weeks later. Visitors were encouraged to enjoy the artwork and engage with it.

A River Remembered

[edit]

Miguel Rodriguez, a team member with Bring Back the Kern collecting photos, videos and stories of the once flowing river for an art exhibit.[55]

The Mighty Kern River

[edit]"The Mighty Kern River" is a children's book in the "Indy, Oh Indy" series created by author Teresa Adamo and illustrator Jennifer Williams-Cordova. The book takes readers on a tour of the Kern River, from its mountain origins to the Buena Vista Lake Aquatic Recreation Area west of Bakersfield. The book was inspired by Bring Back the Kern, a grassroots group raising awareness about Bakersfield's mostly dry river and efforts to revive a more regular flow of water through town.

The book features cute animal characters and easy-to-follow prose to introduce children to the importance of a running river and its benefits to the community and environment. The creators of the "Indy" book series used Kickstarter to fund "The Mighty Kern River," with a goal of $6,500. The book costs $15 and includes a fold-out map of the river. As an added incentive, the creators are offering "extras" for donors, including having a person illustrated into the book or having someone's name painted on the side of a ski boat. The book is set to be released to buyers by August 1.

Bring Back the Kern wrote a foreword for the book to capture some of the river's history and legal issues. The group is promoting the book as a way for readers, young and old, to envision a flowing river "year-round." The state Water Resources Control Board recently announced it would begin the hearing process on the Kern River to determine the allocation of unappropriated water. Bring Back the Kern has been advocating for a hearing and for any available water to be given to the city for use in the riverbed.[56][57]

Legal Action for Restoration and Public Trust Issues

[edit]In December 2022, six environmental groups initiated a lawsuit against the city of Bakersfield, aiming to restore the flow of the Kern River, which had been heavily diverted to supply water to farms. The lawsuit argued that the city's continued allowance of water diversions upstream was harmful to both the environment and the community, violating California's public trust doctrine.

In January 2022, critics, including Attorney Adam Keats, argued that the State Water Resources Control Board was not adequately addressing public interests in its handling of the Kern River water case. The state hearings were not set to consider the impact of water diversion on the environment, recreation, drinking water, or quality of life, collectively known as the "public trust."[58]

Keats argued that the first consideration should be the requirements of the public trust, including the amount of water needed to maintain the river's flow. The Bakersfield group Bring Back the Kern sent a letter to the state requesting that the Water Board direct its Administrative Hearing Officer to include several public trust questions. The group also referenced California Fish and Wildlife Code 5937, which mandates that dam owners must allow enough water into rivers to sustain a fishery. The letter pointed out that the current situation on the Kern River precluded the existence of any fisheries.[59]

Endangered river status

[edit]

The Lower Kern River was listed by American Rivers as one of America's Most Endangered Rivers of 2022.[60] According to American Rivers, "decades of excessive water diversions for agriculture operations have dried up the last 25 miles (40 km) of the Lower Kern River.[61]". Water right holders, use a series of canals, many that run right next to the dry riverbed, to divert water from the natural riverbed and in the process have allowed the Lower Kern River to run dry. Doing so has denied the 500,000 residents of the surrounding communities access to flowing river in direct violation of the public trust doctrine. "Under the Public Trust Doctrine, California is obligated to protect flowing waterways for the benefit of current and future generations."[62]

There are several local groups such as Bring Back the Kern, Kern River Fly Fishers, and The Kern River Parkway Foundation that are working to restore the Lower Kern River.[63]

See also

[edit]- Indigenous peoples of California

- Tübatulabal (the Pahkanapil) of the Central Valley Yokuts

- Palagewan, who lived along the North Fork Kern River into Hot Springs Valley[64]

- Bankalachi (the Toloim), who lived in the Greenhorn Mountains south to Poso Creek around Linns Valley and north to the Tule River[64]

- Kawaiisu (the Nuwa), who lived in the Weldon Valley, the Kelso Valley, and Piute Mountains[64]

- Yawelmani (the Yowlumne), who lived along the Kern River on the east side, north of Kern Lake

- Tübatulabal (the Pahkanapil) of the Central Valley Yokuts

References

[edit]- ^ a b Erwin G. Gudde; William Bright (2004). California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names. University of California Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-520-24217-3. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c d U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Kern River, GNIS

- ^ Google Earth elevation for GNIS coordinates.

- ^ "Boundary Descriptions and Names of Regions, Subregions, Accounting Units and Cataloging Units". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c Water Resources Data California, Water Year 2004, Volume 3, USGS

- ^ ECORP Consulting, Inc. (2007), Tulare Lake basin hydrology and hydrography: a summary of the movement of water and aquatic species (PDF), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, retrieved May 4, 2011

- ^ Buena Vista Aquatic Recreational Area

- ^ a b United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Mount Brewer, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Mount Kaweah, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Chagoopa Falls, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Casa Vieja Meadows, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Hockett Peak, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Durrwood Creek, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Fairview, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Kernville, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Lake Isabella North, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Weldon, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Cirque Peak, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Onyx, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Higgins, Chris T.; Therberge, Albert E. Jr.; Ikelman, Joy A. (1980). Geothermal Resources of California (PDF) (Map). NOAA National Geophysical Center. Sacramento: California Department of Mines and Geology.

- ^ "Lower Kern River". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Rio Bravo Ranch, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Oildale, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ James, Ian (December 18, 2022). "In Bakersfield, a lawsuit aims to turn a dry riverbed into a flowing river". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Haslam, Gerald (1994). The Other California: The Great Central Valley in Life and Letters. University of Nevada Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 0-88496-321-7.

- ^ "Kern". CA State Parks. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

- ^ "150th Anniversary of Fort Tejon Earthquake". January 3, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ "Bakersfield, Ag District Battle Over Use of Kern River Water". The Bakersfield Californian. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Kern River, California". National Wild And Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Golden Trout Creek

- ^ a b Stanley J. Stephens; Christy McGuire; Lisa Sims (September 17, 2004). Conservation Assessment and Strategy for the California Golden Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita) Tulare County, California (PDF) (Report). CDFG, USDA Forest Service, USFWS. p. 91. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Inland Fishes of California, By Peter B. Moyle. Page 20.

- ^ AT THE CROSSROADS: A Report on CALIFORNIA'S ENDANGERED AND RARE FISH AND WILDLIFE. Sacramento, California: California Fish and Game Commission. January 1972 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Stacey Shepard (January 9, 2008). "Kern River beaver may have new home in Tehachapi". Bakersfield.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ "Funston Meadows". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Rattlesnake Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Wendy R. Townsend (1979). Beaver in the upper Kern Canyon, Sequoia National Park. Master's thesis (Thesis). University of California, Fresno. p. 72.

- ^ "Beaver Canyon". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Tappe, Donald T. (1942). "The Status of Beavers in California" (PDF). Game Bulletin No. 3. California Department of Fish & Game: 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Wendy R. Townsend (1979). Beaver in the upper Kern Canyon, Sequoia National Park, Master's thesis (Thesis). University of California, Fresno. p. 72.

- ^ "Panorama Vista Preserve, Bakersfield CA". Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ "The History of Kern River Hatchery". wildlife.ca.gov. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Cox, John. "Hatchery closes down again following three years of renovations". The Bakersfield Californian. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ CDFW (November 23, 2020). "Kern County Fish Hatchery to Close Temporarily for Repairs". CDFW News. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Kern River No. 3 Project FERC No. 2290" (PDF).

- ^ "Kern River advocates accuse utility of "lawless" water diversions on behalf of a long closed fish hatchery". MSN. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Bursztyn, Natalie. "The Kern River, California: A Story of Uplift, Incision, and Flood Control". Science Education Research Center at Carleton College. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "Glaciation of the Upper Kern Basin: Kern Glacier System". Geological Survey Professional Paper 504—A Glacial Reconnaissance of Sequoia National Park California. U.S. National Park Service. August 3, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "Geology of the Kern River Valley". Audubon Society. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Kern River Field at 100 Archived 2001-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. Article on the Kern River Oil Field in the Bakersfield Californian, April 27, 1999.

- ^ "Forest Service: Campgrounds in Sequoia National Forest (Kern River is at the South End)". Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Price, Robert (May 27, 2023). "Kern River drownings hit 325 since 1968, but warning out-of-town visitors remains primary challenge". KGET 17. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (May 12, 2016). "Merle Haggard's Final Recording 'Kern River Blues' Has Arrived". Billboard. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ "Home". Bring Back the Kern. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ "A River Remembered". Bring Back the Kern. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ ""The Mighty Kern River"". IndyOhIndy. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ "SJVWater". April 15, 2021.

- ^ "State is asking the wrong questions on Kern River water case, critics argue". KVPR | Valley Public Radio. January 14, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2023.

- ^ "In Bakersfield, a lawsuit aims to turn a dry riverbed into a flowing river". Los Angeles Times. December 18, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2023.

- ^ "Lower Kern River". Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ "America's Most Endangered Rivers® of 2022" (PDF). American Rivers. 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Americas Most Endangered Rivers (PDF) (Report). April 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "In Bakersfield, many push for bringing back the flow of the long-dry Kern River". Los Angeles Times. December 9, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c kern.aubudon.org

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch