Panoramic painting

Panoramic paintings are massive artworks that reveal a wide, all-encompassing view of a particular subject, often a landscape, military battle, or historical event. They became especially popular in the 19th century in Europe and the United States, inciting opposition from some writers of Romantic poetry. A few have survived into the 21st century and are on public display. Typically shown in rotundas for viewing, panoramas were meant to be so lifelike they confused the spectator between what was real and what was image.[1]

In China, panoramic paintings are an important subset of handscroll paintings, with some famous examples being Along the River During the Qingming Festival and Ten Thousand Miles of the Yangtze River.

History

[edit]The word "panorama", a portmanteau of the Greek words ‘pano’ (all) and ‘horama’ (view), was coined by the Irish painter Robert Barker in 1787.[1] While walking on Calton Hill overlooking Edinburgh, the idea struck him and he obtained a patent for it the same year.[1] Barker's patent included the first coining of the word panorama.[2] Barker's vision was to capture the magnificence of a scene from every angle so as to immerse the spectator completely, and in so doing, blur the line where art stopped and reality began.[1] Barker's first panorama was of Edinburgh.[1] He exhibited the Panorama of Edinburgh From Calton Hill[3] in his house in 1788, and later in Archers' Hall near the Meadows to public acclaim.[1] The first panorama disappointed Barker, not because of its lack of success, but because it fell short of his vision.[1] The Edinburgh scene was not a full 360 degrees; it was semi-circular.[1]

In 1792 he used the term to describe his paintings of Edinburgh, Scotland, shown on a cylindrical surface, which he soon was exhibiting in London, as "The Panorama".

After the commercial but limited technical success of his first panorama, Barker and his son Henry Aston Barker completed a panorama of London from the Albion Mills.[1] A reduced version was originally shown in their house with a larger one on display later.[1]

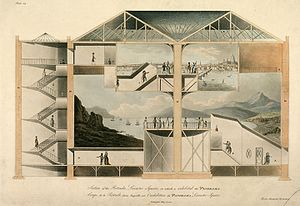

To fulfill his dream of a 360 panorama, Barker and his son purchased a rotunda at Leicester Square.[1] London from the Roof of the Albion Mills christened the new rotunda, all 250 square meters of it.[1] The previously reduced version, in contrast, measured only 137 square meters.[1] The rotunda at Leicester Square was composed of two levels, although they varied in size.[1] Spectators observed the scenes from a platform in the center of the rotunda.[4]

In 1793 Barker moved his panoramas to the first brick panorama rotunda building in the world, in Leicester Square, and made a fortune. Viewers flocked to pay a stiff 3 shillings to stand on a central platform under a skylight, which offered an even lighting, and get an experience that was "panoramic" (an adjective that didn't appear in print until 1813). The extended meaning of a "comprehensive survey" of a subject followed sooner, in 1801. Visitors to Barker's Panorama of London, painted as if viewed from the roof of Albion Mills on the South Bank, could purchase a series of six prints that modestly recalled the experience; end-to-end the prints stretched 3.25 metres. In contrast, the actual panorama spanned 250 square metres.[5]

The main goal of the panorama was to immerse the audience to the point where they could not tell the difference between the canvas and reality, in other words, wholeness.[4] To accomplish this, all borders of the canvas had to be concealed.[4] Props were also strategically positioned in the foreground of the scene to increase realism.[4] Two windows laid into the roof allowed natural light to flood the canvases, also making the illusion more realistic.[1] Two scenes could be exhibited at the rotunda in Leicester Square simultaneously; however, the rotunda at Leicester Square was the only rotunda to house two panoramas. Houses with single scenes proved more popular.[1] While at Leicester Square, the audience was herded down a long, dark corridor to clear their minds.[1] The idea was to have spectators more or less forget what they just saw, leaving their minds blank to view the second scene.[1] Despite the audience's "mind blanking" walk in the dark, panoramas were designed to have a lingering effect upon the viewer.[4] For some, this attribute placed panoramas in the same category as propaganda of the period: no more than an illusion meant to deceive.[4]

Barker's accomplishment involved sophisticated manipulations of perspective not encountered in the panorama's predecessors, the wide-angle "prospect" of a city familiar since the 16th century, or Wenceslas Hollar's Long View of London from Bankside, etched on several contiguous sheets. When Barker first patented his technique in 1787, he had given it a French title: La Nature à Coup d' Oeil ("Nature at a glance"). A sensibility to the "picturesque" was developing among the educated class, and as they toured picturesque districts, like the Lake District, they might have in the carriage with them a large lens set in a picture frame, a "landscape glass" that would contract a wide view into a "picture" when held at arm's length.

Barker made many efforts to increase the realism of his scenes. To fully immerse the audience in the scene, all borders of the canvas were concealed.[6] Props were also strategically positioned on the platform where the audience stood and two windows were laid into the roof to allow natural light to flood the canvases.[7]

Two scenes could be exhibited in the rotunda simultaneously; however, the rotunda at Leicester Square was the only one to do so.[8] Houses with single scenes proved more popular to audiences as the fame of the panorama spread.[8] Because the Leicester Square rotunda housed two panoramas, Barker needed a mechanism to clear the minds of the audience as they moved from one panorama to the other. To accomplish this, patrons walked down a dark corridor and up a long flight of stairs where their minds were supposed to be refreshed for viewing the new scene.[9] Due to the immense size of the panorama, patrons were given orientation plans to help them navigate the scene.[10] These glorified maps pinpointed key buildings, sites, or events exhibited on the canvas.[10]

To create a panorama, artists travelled to the sites and sketched the scenes multiple times.[11] Typically a team of artists worked on one project with each team specializing in a certain aspect of the painting such as landscapes, people or skies.[11] After completing their sketches, the artists typically consulted other paintings, of average size, to add further detail.[11] Martin Meisel described the panorama: "In its impact, the Panorama was a comprehensive form, the representation not of the segment of a world, but of a world entire seen from a focal height."[12] Though the artists painstakingly documented every detail of a scene, by doing so they created a world complete in and of itself.[13]

The first panoramas depicted urban settings, such as cities, while later panoramas depicted nature and famous military battles.[14] The necessity for military scenes increased in part because so many were taking place. French battles commonly found their way to rotundas thanks to the feisty leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte.[8] Henry Aston Barker's travels to France during the Peace of Amiens led him to court, where Bonaparte accepted him.[8] Henry Aston created panoramas of Bonaparte's battles including The Battle of Waterloo, which saw so much success that he retired after finishing it.[15] Henry Aston's relationship with Bonaparte continued following Bonaparte's exile to Elba, where Henry Aston visited the former emperor.[8] Pierre Prévost (painter) (1764–1823) was the first important French panorama painter. Among his 17 panoramas, the most famous describe the cities of Rome, Naples, Amsterdam, Jerusalem, Athens and also the battle of Wagram.

Outside of England and France, the popularity of panoramas depended on the type of scene displayed. Typically, people wanted to see images from their own countries or from England. This principle rang true in Switzerland, where views of the Alps dominated.[16] Likewise in America, New York City panoramas found popularity, as well as imports from Barker's rotunda.[17] As painter John Vanderlyn soon found out, French politics did not interest Americans.[18] In particular, his depiction of Louis XVIII's return to the throne did not live two months in the rotunda before a new panorama took its place.[18]

Barker's Panorama was hugely successful and spawned a series of "immersive" panoramas: the Museum of London's curators found mention of 126 panoramas that were exhibited between 1793 and 1863. In Europe, panoramas were created of historical events and battles, notably by the Russian painter Franz Roubaud. Most major European cities featured more than one purpose-built structure hosting panoramas. These large fixed-circle panoramas declined in popularity in the latter third of the nineteenth century, though in the United States they experienced a partial revival; in this period, they were more commonly referred to as cycloramas.

The panorama competed for audiences most frequently with the diorama, a slightly curved or flat canvas extending 22 by 14 metres.[19] The diorama was invented in 1822 by Louis Daguerre and Charles-Marie Bouton, the latter a former student of the renowned French painter Jacques-Louis David.[19]

Unlike the panorama where spectators had to move to view the scene, the scenes on the diorama moved so the audience could remain seated.[20] Accomplished with four screens on a roundabout, the illusion captivated 350 spectators at a time for a period of 15 minutes.[20] The images rotated in a 73 degree arc, focusing on two of the four scenes while the remaining two were prepared, which allowed the canvases to be refreshed throughout the course of the show.[12][20] While topographical detail was crucial to panoramas, as evidenced by the teams of artists who worked on them, the effect of the illusion took precedence with the diorama.[21] Painters of the diorama also added their own twist to the panorama's props, but instead of props to make the scenes more real, they incorporated sounds.[21] Another similarity to the panorama was the effect the diorama had on its audience. Some patrons experienced a stupor, while others were alienated by the spectacle.[22] The alienation of the diorama was caused by the connection the scene drew to art, nature and death.[23] After Daguerre and Bouton's first exhibition in London, one reviewer noted a stillness like that "of the grave."[23] To remedy this tomblike atmosphere Daguerre painted both sides of the canvas, known as "the double effect."[23] By lighting both painted sides of the canvas, light was transmitted and reflected producing a type of transparency producing the effect of time passing.[12] This effect gave the crew operating the lights and turning the roundabout a new type of control over the audience than the panorama ever had.[12]

In Britain and particularly in the US, the panoramic ideal was intensified by unrolling a canvas-backed scroll past the viewer in a Moving Panorama, an alteration of an idea that was familiar in the hand-held landscape scrolls of Song dynasty. First unveiled in 1809 in Edinburgh, Scotland, the moving panorama required a large canvas and two vertical rollers to be set up on a stage.[24] Peter Marshall added the twist to Barker's original creation, which saw success throughout the 19th and into the 20th century.[24] The scene or variation of scenes passed between the rollers, eliminating the need to showcase and view the panorama in a rotunda.[24] A precursor to "moving" pictures, the moving panorama incorporated music, sound effects and stand-alone cut-outs to create their mobile effect.[12] Such a traveling motion allowed for new types of scenes, such as chase sequences, that could not be produced so well in either the diorama or the panorama.[25] In contrast specifically to the diorama, where the audience seemed to be physically rotated, the moving panorama gave patrons a new perspective, allowing them to "[function] as a moving eye".[12]

The panorama evolved somewhat and in 1809, the moving panorama graced the stage in Edinburgh.[26] Unlike its predecessor, the moving panorama required a large canvas and two vertical rollers.[26] The scene or variation of scenes passed before the audience between the rollers, eliminating the need to showcase and view the panoramas in a rotunda.[26] Peter Marshall added the twist to Barker's original creation, which saw success throughout the 19th and into the 20th century.[26] Despite the success of the moving panorama, Barker's original vision maintained popularity through various artists, including Pierre Prévost, Charles Langlois and Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux among others.[26] The revival in popularity for the panorama peaked in the 1880s, having spread through Europe and North America.[26]

Romantic criticism of panoramas

[edit]The panorama's rise in popularity was a result of its accessibility in that people did not need a certain level of education to enjoy the views it offered.[27] Accordingly, patrons from across the social scale flocked to rotundas throughout Europe.[27]

While easy access was an attraction of the panorama, some people believed it was nothing more than a parlor trick bent on deceiving its public audience. Designed to have a lingering effect upon the viewer, the panorama was placed in the same category as propaganda of the period, which was also seen as deceitful.[28] The locality paradox also attributed to the arguments of panorama critics.[6] A phenomenon resulting from immersion in a panorama, the locality paradox happened when people were unable to distinguish where they were: in the rotunda or at the scene they were seeing.[6]

People could immerse themselves in the scene and take part in what became known as the locality paradox.[6] The locality paradox refers to the phenomenon where spectators are so taken with the panorama they cannot distinguish where they are: Leicester Square or, for example, the Albion Mills.[6] This association with delusion was a common critique of panoramas. Writers also feared the panorama for the simplicity of its illusion. Hester Piozzi was among those who rebelled against the growing popularity of the panorama for precisely this reason.[27] She did not like seeing so many people – elite and otherwise – fooled by something so simple.[27]

Another problem with the panorama was what it came to be associated with, namely, by redefining the sublime to incorporate the material.[29] In their earliest forms, panoramas depicted topographical scenes and in so doing, made the sublime accessible to every person with 3 shillings in his or her pocket.[30] The sublime became an everyday thing and therefore, a material commodity. By associating the sublime with the material, the panorama was seen as a threat to romanticism, which was obsessed with the sublime.[31] According to the romantics, the sublime was never supposed to include materiality and by linking the two, panoramas tainted the sublime.

The poet William Wordsworth has long been characterized as an opponent of the panorama, most notably for his allusion to it in Book Seven of The Prelude.[32] It has been argued that Wordsworth's problem with the panorama was the deceit it used to gain popularity.[33] He felt, critics say, that the panorama not only exhibited an immense scene of some kind, but also the weakness of human intelligence.[32] Wordsworth was offended by the fact that so many people found panoramas irresistible and concluded that people were not smart enough to see through the charade.[32] Because of his argument in The Prelude, it is safe to assume Wordsworth saw a panorama at some point during his life, but it is unknown which one he saw; there is no substantial proof he ever went, other than his description in the poem.[34]

However, Wordsworth's hatred of the panorama was not limited to its deceit. The panorama's association with the sublime was likewise offensive to the poet as were other spectacles of the period that competed with reality.[35][36] As a poet, Wordsworth sought to separate his craft from the phantasmagoria enveloping the population.[37] In this context, phantasmagoria refers to signs and other circulated propaganda, including billboards, illustrated newspapers and panoramas themselves.[38] Wordsworth's biggest problem with panoramas was their pretense: the panorama lulled spectators into stupors, inhibiting their ability to imagine things for themselves.[33] For Wordsworth, panoramas more or less brainwashed their audiences.[39] Perhaps Wordsworth's biggest problem with panoramas was their popularity.[39] Wordsworth wanted people to see the representation depicted in the panorama and appreciate it for what it was – art.[32]

Conversely, J. Jennifer Jones argues Wordsworth was not opposed to the panorama, but rather hesitant about it.[34] In her essay, "Absorbing Hesitation: Wordsworth and the Theory of the Panorama", Jones argues that other episodes of The Prelude have just as much sensory depth as panoramas are supposed to have had.[34] Jones studied how Wordsworth imitated the senses in The Prelude, much in the same way panoramas did.[34] She concluded that panoramas were a balancing act between what the senses absorbed and what they came away with, something also present in Wordsworth's poetry.[34] By her results then, Wordsworth's similar imitation of the senses proves he was not entirely opposed to them.

The subjects of panoramas transformed as time passed, becoming less about the sublime and more about military battles and biblical scenes.[26] This was especially true during the Napoleonic era when panoramas often displayed scenes from the emperor's latest battle whether a victory or a crushing defeat such as depicted in the Battle of Waterloo in 1816.[26][40]

A modern take on the panorama believes the enormous paintings filled a hole in the lives of those who lived during the nineteenth century.[1] Bernard Comment said in his book The Painted Panorama, that the masses needed "absolute dominance" and the illusion offered by the panorama gave them a sense of organization and control.[1] Despite the power it wielded, the panorama detached audiences from the scene they viewed, replacing reality and encouraging them to watch the world rather than experience it.[1]

Surviving panoramas

[edit]Relatively few of these unwieldy ephemera survive. The oldest known surviving panorama (completed in 1814 by Marquard Wocher) is on display at Schadau Castle, depicting an average morning in the Swiss town of Thun. As of today it is owned by the Gottfried Keller Foundation.[41][42] Another rare surviving great-circle panorama is the Panorama Mesdag, completed in 1881 and housed in a purpose-built museum in The Hague, showing the dunes of nearby Scheveningen. Both of these works are considered of interest as they depict domestic scenes of their times. Depictions of warfare were more common as subject matter, an example of which is located at the battlefield of Waterloo, depicting the battle.

An exhibition "Panoramania" was held at the Barbican in the 1980s, with a catalog by Ralph Hyde. The Racławice Panorama, currently located in Wrocław, Poland, is a monumental (15 × 120 metre) panoramic painting depicting the Battle of Racławice, during the Kościuszko Uprising. A panorama of the Battle of Stalingrad is on display at Mamayev Kurgan. Among Franz Roubaud's great panoramas, those depicting the Siege of Sevastopol (1905) and Battle of Borodino (1911) survive, although the former was damaged during the Siege of Sevastopol (1942) and the latter was transferred to Poklonnaya Gora. The Pleven Panorama in Pleven, Bulgaria, depicts the events of the Siege of Plevna in 1877 on a 115×15-metre canvas with a 12-meter foreground.

Five large panoramas survive in North America: the Cyclorama of Jerusalem (a.k.a. the Panorama of Jerusalem at the Moment of Christ's Death) at St. Anne, outside of Quebec City; the Gettysburg Cyclorama depicting Pickett's Charge during the Battle of Gettysburg in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; John Vanderlyn's Panorama of the Garden and Palace of Versailles at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Atlanta Cyclorama, which depicts the Battle of Atlanta, in Atlanta, Georgia. A fifth panorama, also depicting the Battle of Gettysburg, was willed in 1996 to Wake Forest University in North Carolina; it is in poor condition and not on public display. It was purchased in 2007 by a group of North Carolina investors who hope to resell it to someone willing to restore it. Only pieces survive of a massive cyclorama depicting the Battle of Shiloh.

In the area of the moving panorama, there are somewhat more extant, though many are in poor repair and the conservation of such enormous paintings poses very expensive problems. The most notable rediscovered panorama in the United States was the Great Moving Panorama of Pilgrim's Progress, which was found in storage at the York Institute now the Saco Museum in Saco, Maine, by its former curator Tom Hardiman. It was found to incorporate designs by many of the leading painters of its day, including Jasper Francis Cropsey, Frederic Edwin Church, and Henry Courtney Selous (Selous was the in-house painter for the original Barker panorama in London for many years.)

The St. Louis Art Museum owns another moving panorama, which it is conserving in public during the summers of 2011 and 2012. "The Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley"—the only remaining of six known Mississippi River panorama paintings—measures 2.3 metres (90 inches) wide by 106 metres (348 feet) long and was commissioned c. 1850 by an eccentric amateur archaeologist named Montroville W. Dickeson. Judith H. Dobrzynski wrote about the restoration in an article in the Wall Street Journal dated June 27, 2012.

In 1918, the New Bedford Whaling Museum acquired the Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage Round the World, created by artists Benjamin Russell and Caleb Purrington in 1848. At about 395 m (1,295 ft) long and 2.6 m (8+1⁄2 ft) high, it is one of the largest surviving moving panoramas (although far short of the "Three Miles [4800 m] of Canvass" advertised by its creators in their handbills). The museum is currently planning for the conservation Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine of the Grand Panorama. Although in storage, highlights may be seen on the museum's Flickr pages

Another moving panorama was donated to the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University Library in 2005. Painted in Nottingham, England around 1860 by John James Story (d. 1900), it depicts the life and career of the great Italian patriot, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882). The panorama stands about 1.4 m (4+1⁄2 ft) high and 83 m (273 ft) long, painted on both sides in watercolor. Numerous battles and other dramatic events in his life are depicted in 42 scenes, and the original narration written in ink survives.[citation needed]

The Arrival of the Hungarians, a vast cyclorama by Árpád Feszty et al., completed in 1894, is displayed at the Ópusztaszer National Heritage Park in Hungary. It was made to commemorate the 1000th anniversary of the 895 conquest of the Carpathian Basin by the Hungarians.[citation needed]

The Cyclorama of Early Melbourne, by artist John Hennings in 1892, still survives albeit having suffered water damage during a fire.[43] Painted from a panoramic sketch of Early Melbourne in 1842 by Samuel Jackson. It places the viewer on top of the partially constructed Scott's Church on Collins Street in the Melbourne CBD. Commissioned to celebrate 50 years of the city of Melbourne, it was displayed in the Melbourne Exhibition Building for nearly 30 years before being taken into storage. Relatively small for a Cyclorama, it measured 36 m (118 ft) long and 4 m (13 ft) high.[44]

The Biological museum (Stockholm), founded by hunter and taxidermist Gustaf Kolthoff, opened its dioramas to the public in November 1893 and is still an active museum with about 15000 visitors yearly. The museum has panorama paintings by Bruno Liljefors (assisted by Gustaf Fjæstad), Kjell Kolthoff and several hundred preserved animals in their natural habitats.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Cinéorama

- Cyclorama

- Hanging scroll

- International Panorama Council

- Moving panorama

- Mareorama

- Myriorama

- Panorama (perspective)

- Panstereorama

- Trans-Siberian Railway Panorama

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Comment 1999, p. 19

- ^ "Lost Edinburgh: Calton Hill and the invention of the panorama". The Scotsman. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "The panorama of Edinburgh from Calton Hill". Treasures from University Collections 2011. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas, Sophie. "Making Visible: The Diorama, the Double and the (Gothic) subject." Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era. Ed. Robert Miles. 2005. Praxis Series. 31 January 2010. "Thomas -"Making Visible: The Diorama, the Double and the (Gothic) Subject"- Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era - Praxis Series - Romantic Circles". Archived from the original on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2010..

- ^ Comment 1999, p. 23

- ^ a b c d e Ellis 2008, p. 144

- ^ Comment 1999, p. 7-8

- ^ a b c d e Comment 1999, p. 24

- ^ Thomas 2005, p. 10

- ^ a b Comment 1999, p. 161

- ^ a b c Comment 1999, p. 182

- ^ a b c d e f Meisel 1983, p. 62

- ^ Thomas 2005, p. 14

- ^ Comment 1999, pp. 23–25

- ^ Comment 1999, p. 25

- ^ Comment 1999, p. 53

- ^ Comment 1999, p. 55-56

- ^ a b Comment 1999, p. 56

- ^ a b Comment 1999, p. 57

- ^ a b c Comment 1999, p. 58

- ^ a b Thomas 2005, p. 11

- ^ Thomas 2005, p. 12-13

- ^ a b c Thomas 2005, p. 13-14

- ^ a b c Wilcox 2007, p. 2

- ^ Meisel, 1983, p. 62

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilcox, Scott. Panorama Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 9 February 2010.

- ^ a b c d Ellis 2008, p. 142

- ^ Thomas 2005, p. 20

- ^ Jones 2006, p. 360

- ^ Wilcox 2007, p. 1

- ^ Jones 2006, p.360

- ^ a b c d Ellis 2008, p. 145

- ^ a b Haut 2009, p. 314

- ^ a b c d e Jones 2006, p. 364

- ^ Miles 2005, p. 14

- ^ Miles, Robert. "Introduction: Gothic Romance as Visual Technology." Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era. Ed. Robert Miles. 2005. Praxis Series. 31 January 2010. "Thomas -"Making Visible: The Diorama, the Double and the (Gothic) Subject"- Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era - Praxis Series - Romantic Circles". Archived from the original on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2010..

- ^ Miles 2005, p. 18

- ^ Miles 2005, pp. 14–15

- ^ a b Haut, Asia. "Reading the Visual." Oxford Art Journal: 32, 2, 2009.

- ^ Meisel, Martin. Realizations. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1983.

- ^ Claude Lapaire (14 November 2006). "Gottfried Keller-Stiftung" (in German). HDS. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ "Bund greift Gottfried-Keller-Stiftung unter die Arme" (in German). Der Landbote/sda. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ "Only Melbourne Cyclorama of Early Melbourne". Only Melbourne. Ripefruit Media Co. 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ "eMelbourne Cycloramas". eMelbourne - The Encyclopedia of Melbourne Online. School of Historical & Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne. 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

References

[edit]- Richard Altick, The Shows of London. New York: Belnap, 1978.

- Bernard Comment, The Painted Panorama. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999.

- Markman Ellis. Spectacles within doors: Panoramas of London in the 1790s. Romanticism 2008, Vol. 14 Issue 2. Modern Language Association International Bibliography Database.

- Asia Haut. "Reading the Visual." Oxford Art Journal: 32, 2, 2009.

- Ralph Hyde, Panoramania, 1988 (exhibition catalog)

- J. Jennifer Jones. Absorbing Hesitation: Wordsworth and the Theory of the Panorama. Studies in Romanticism. 45:3, 2006. Modern Language Association International Bibliography Database.

- Gabriele Koller, (ed.), Die Welt der Panoramen. Zehn Jahre Internationale Panorama Konferenzen / The World of Panoramas. Ten Years of International Panorama Conferences, Amberg 2003

- Martin Meisel. Realizations. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1983.

- Robert Miles. "Introduction: Gothic Romance as Visual Technology." Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era. Ed. Robert Miles. 2005. Praxis Series. 31 Jan. 2010. https://archive.today/20121215042002/http://romantic.arhu.umd.edu/praxis/gothic/thomas/thomas.html

- Stephan Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium (MIT Press)

- Sophie Thomas. "Making Visible: The Diorama, the Double and the (Gothic) subject." Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era. Ed. Robert Miles. 2005. Praxis Series. 31 Jan. 2010. https://archive.today/20121215042002/http://romantic.arhu.umd.edu/praxis/gothic/thomas/thomas.html

- Scott Wilcox. "Panorama." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, 2007. 9 Feb. 2010. <http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T065087>

- Scott Barnes Wilcox, The Panorama and Related Exhibitions in London. M. Litt. University of Edinburgh, 1976.

External links

[edit]- "The 'Panorama'": Edinburgh's panorama

- Panorama of London from Albion Mills: a semi-circular view in hand watercolored prints

- Museum of London website Panoramania!

- Website of the International Panorama Council IPC listing all existing panoramas and cycloramas worldwide

- Garibaldi & the Risorgimento

- Thomas -"Making Visible: The Diorama, the Double and the (Gothic) Subject"- Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era - Praxis Series - Romantic Circles

- "Unlimiting the Bounds": the Panorama and the Balloon View

- Mobile Cyclorama . Virtual Panoramic 360° View Paintings

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch