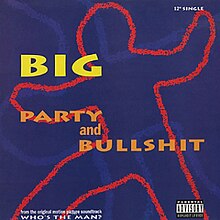

Party and Bullshit

| "Party and Bullshit" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by The Notorious B.I.G. | ||||

| from the album Who's the Man?: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | ||||

| Released | June 29, 1993 | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 3:43 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Songwriter(s) | Christopher Wallace | |||

| Producer(s) | Easy Mo Bee | |||

| The Notorious B.I.G. singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Party and Bullshit" is a song by the American hip hop artist The Notorious B.I.G., credited as BIG. Released on June 29, 1993, as the fourth single from the soundtrack to the film Who's the Man? (1993), "Party and Bullshit" was the rapper's debut single.

Background

[edit]Christopher Wallace, born and raised in Brooklyn, New York City, during the emergence of the hip-hop scene, developed a passion for music at a young age.[1] There, he met the saxophonist Donald Harrison, who introduced him to jazz. Wallace recorded one of his first songs in Harrison’s home studio.[2] However, growing up during the crack epidemic,[3] Wallace decided to focus on selling drugs, while still rapping as a hobby.[4] According to The New York Times, "as a boy he preferred hanging around gamblers and drug dealers to sitting in a classroom". He dropped out of school in the tenth grade.[5] To increase his drug-sale profits,[6][7] he moved to North Carolina, where, at the age of 17, he was arrested and spent nine months in jail.[8]

Upon release from jail, Wallace, known at the time as Biggie Smalls,[a] decided to focus more on music.[10] Back in Brooklyn, his friend DJ 50 Grand introduced him to Big Daddy Kane's DJ, Mister Cee.[11] Enthusiastic about Biggie's rapping, Mister Cee convinced him to record a demo and send it to The Source magazine's column "Unsigned Hype", which showcased up-and-coming rap talents. Biggie remained skeptical but agreed.[12] Impressed with the demo, the column's editor Matteo "Matty C" Capoluongo recommended him to Sean "Puffy" Combs,[13] a young intern who by now was the vice president of A&R at Uptown Records.[13][14] Combs helped Biggie get signed to Uptown.[15] "Party and Bullshit" was Biggie's commercial debut,[16] released after he was featured on several songs from other artists of the label.[17]

Recording

[edit]In 1992, Uptown Records and MCA Records signed a $50 million deal, which led to Uptown producing the soundtrack for the movie Who's the Man? (1993).[18] Puffy, who was responsible for the soundtrack, decided to include his new artist, Biggie.[16]

"Party and Bullshit" was recorded at Soundtrack Studios in New York.[19] According to the song's producer Easy Mo Bee, it was recorded in one take. Biggie brought his friends from the group Junior M.A.F.I.A. for the recording session, they ordered food and were resting in the studio. Anxious about wasting expensive studio time, Easy Mo Bee kept asking him when they would start recording. "And he kept telling me, 'Yo, I got you, man.' Ordering food, eating burgers. And then he just jumped up and went right into the booth and just spat three verses. I was like, 'Yo, who is this dude?' I thought he was playing the whole time", said the producer.[20]

In an interview with Vibe magazine, Biggie revealed that the original version of the song differed from the released version. The rapper explained that Andre Harrell, CEO of Uptown Records, asked him to record a party song.[21]

Composition

[edit]"Party and Bullshit" is an East Coast hip hop song.[22] The main melody of the song is a loop, made by blending two samples: the siren from the song "UFO" by the band ESG and the organ from Johnny "Hammond" Smith's cover of "I'll Be There" by the Jackson 5. Nate Patrin of Stereogum wrote that the samples "melt into each other to sound richer", resulting in a track that "sounds amped and mellow at the same time".[23]

The song begins with Biggie describing his early teenage years: calling himself a "terror since the public school era", talking about skipping classes and smoking marijuana daily. He then describes a modern day party, where he and all his friends brought firearms.[24] Throughout the song, he references numerous alcoholic beverages.[25] Towards the end of the third verse music stops and a small skit is played, portraying a fight at the party. After the fight ends, Biggie continues rapping with the phrase "Can't we just all get along?", alluding to the quote from the victim of police brutality Rodney King.[26][27]

The song's chorus is built around the "party and bullshit" chant,[24] which is an interpolation of the phrase from the 1968 song "When the Revolution Comes" by the spoken word group the Last Poets.[28] However, Biggie altered its meaning: the original song sarcastically criticized young black people who ignored the fight for equality in favor of leisure and meaningless activities, while his song emphasized these activities,[26][27] turning into what Sia Michel of Spin magazine called a "good-time anthem".[29] Discussing the use of the phrase, Abiodun Oyewole of the Last Poets said: "When we rapped, it was all about raising consciousness and using language to challenge people. When I wrote [about] 'party and bullshit' it was to make people get off their ass. But now 'party and bullshit' was used by Biggie, used by Busta Rhymes, but in a non-conscious way."[30] In his book Unbelievable, Cheo Hodari Coker argued that "Party and Bullshit" had a deeper meaning. The journalist wrote that the lyrics provided a social commentary, highlighting the problems of young men who grew up during the crack epidemic and desired to get rich.[27]

Release

[edit]"Party and Bullshit" was released on June 29, 1993,[31] through Uptown Records.[17] It was the fourth single from the soundtrack to the film Who's the Man? (1993) and Biggie's debut single.[32][33] Apart from the song itself, the single also included two remixes, by Puff Daddy and Lord Finesse, which used different, jazzy instrumentals.[34] "Party and Bullshit" did not chart and has not received a RIAA certification;[35][36] however, it has sold 500,000 copies.[37][24] S. H. Fernando Jr. of Rolling Stone magazine described it as an "underground smash",[38] while the journalist Ronin Ro wrote that the song was a hit on radio stations and in nightclubs. According to him, following the release, other famous rappers would approach Biggie in nightclubs to shake his hand and praise him.[24]

Critical reception

[edit]In a contemporary review, Reginald C. Dennis of The Source magazine called the song a "hardcore debut" that "livens things up" on the soundtrack. The journalist praised Biggie's performance, referring to him as "the star of the album".[39] Cheo Hodari Coker, in his book Unbelievable, commended the song, calling it a "fine vehicle for his storytelling skills and playful yet commanding cadence", that creates a colorful depiction of the Brooklyn night life.[34] IGN described it as "considerably rawer" than the rapper's later songs, "showcas[ing] his strong willed cadence and propensity for catchy rhyming verses".[40] Discussing the song, Ekow Eshun of The Independent said he was "mesmerised" after the first listen. "His lyrics turn the vernacular into the spectacular, delivering narrative with breathless ease", stated the journalist.[41]

Legacy

[edit]Remixes

[edit]In the late 1990s, Puff Daddy had plans to record a remix of "Party and Bullshit" for Biggie's posthumous compilation album Born Again (1999). The remix was supposed to feature Will Smith and a chorus from Faith Evans.[42] The song has not been released officially.[43]

In the following years, several artists remixed "Party and Bullshit". In 2007, the electronic duo Ratatat remixed it for their album Ratatat Remixes Vol. 2.[44] The G-Unit rapper Lloyd Banks released "Party N Bullshit" on his mixtape Halloween Havoc (2008).[45] Andrew Hathaway released a mashup of "Party and Bullshit" and Miley Cyrus song "Party in the U.S.A.".[46][47] In 2015, Richie Branson and Solar Slim remixed the song for their Star Wars-themed mashup Life After Death Star.[48][49]

Samples and copyright lawsuit

[edit]Numerous artists sampled "Party and Bullshit", including Rah Digga,[50] Busta Rhymes, Young M.A., Cypress Hill, MF Doom, Jean Grae, and Joell Ortiz.[35] Rita Ora's 2012 song "How We Do (Party)" interpolates the lyrics of "Party and Bullshit".[31]

In 2016, Abiodun Oyewole, a founding member of the Last Poets, sued the Notorious B.I.G. estate for US$24 million in damages.[51] Oyewole claimed that the use of the phrase "party and bullshit", taken from the spoken word group's 1968 song "When the Revolution Comes", constituted copyright infringement.[28] The list of defendants also included executive producer Puff Daddy, producer Easy Moe Bee, and Rita Ora, along with several producers and songwriters of her song "How We Do (Party)". Initially, the lawsuit listed Busta Rhymes and Eminem, whose track "Calm Down" also sampled "Party and Bullshit", but Oyewole later dropped these claims voluntarily.[52] After several years of legal battles, in 2019, the New York federal judge Robert Katzmann ruled that the use of the phrase in "Party and Bullshit" is within fair use.[53]

Track listing

[edit]- Commercial 12-inch vinyl single[54]

-

- Side A

- "Party and Bullshit" (Album Version) – 3:42

- "Party and Bullshit" (Puffy's Dirty) – 4:07

- Side B

- "Party and Bullshit" (Lord's Dirty) – 4:15

- Promotional 12-inch vinyl single[55]

-

- Side A

- "Party and Bullshit" (Radio) – 3:42

- "Party and Bullshit" (Album) – 3:42

- "Party and Bullshit" (Instrumental) – 3:42

- Side B

- "Party and Bullshit" (Club Dirty) – 3:42

- "Party and Bullshit" (Dirty Instrumental) – 3:42

Personnel

[edit]Credits are adapted from the single's liner notes.[55]

- Buttnaked Tim Dawg – co-producer

- James Earl Jones, Jr. – co-producer

- Sean "Puffy" Combs – executive producer

- Andre Harrell – executive producer

- Mark Siegal – executive producer

- Toby Emmerich – music supervisor

- Kathy Nelson – music supervisor

- Easy Mo Bee – producer

- Jonnie “Most” Davis - recording/mix engineer

Notes

[edit]- ^ Prior to the release of his debut album Ready to Die (1994), he was forced to change his stage name to the Notorious B.I.G. This change was prompted by a lawsuit from Calvin Lockhart, who played the character Biggie Smalls in the movie Let's Do It Again (1975).[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Coker 2003, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Coker 2003, p. 49.

- ^ Williams, Todd "Stereo" (October 16, 2019). "Notorious B.I.G.'s 'Ready to Die' Forever Changed the Course of Hip-Hop 25 Years Ago". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 19, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Coker 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Marriott, Michel (March 17, 1997). "The Short Life of a Rap Star, Shadowed by Many Troubles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Coker 2003, p. 78.

- ^ Rodriguez, Jayson (January 13, 2009). "'Notorious' Exclusive Clip: Biggie Is Born". MTV. Archived from the original on March 19, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ "Rap Artist Arrested In Assault With Bat". The New York Times. March 24, 1996. Archived from the original on March 19, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Penrose, Nerisha (June 20, 2017). "JAY-Z & More Rappers Who Have Changed Their Names Over the Years". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 19, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (May 4, 2022). "The Number Ones: The Notorious B.I.G.'s "Hypnotize"". Stereogum. Archived from the original on November 28, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Coker 2003, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Coker 2003, p. 54.

- ^ a b Coker 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Swash, Rosie (June 12, 2011). "Sean Combs founds Bad Boy and releases Biggie's debut". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Coker 2003, p. 76, 78–79.

- ^ a b Coker 2003, p. 80.

- ^ a b Coker 2003, p. 304.

- ^ Brown, Preezy (June 15, 2023). "Hip-Hop's Most Impactful Black Founders And Moguls". Vibe. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Ro 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Abrams 2022, p. 428.

- ^ Valdez, Mimi (August 1994). "Next: The Notorious B.I.G.". Vibe. Vol. 2, no. 6. New York. p. 42.

- ^ "100 Greatest Hip-Hop Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. June 2, 2017. Archived from the original on March 21, 2024. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ Patrin, Nate (April 23, 2019). "ESG's "UFO": The Song's Legacy In Samples". Stereogum. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Ro 2001, p. 38.

- ^ Ashworth, Louis (February 27, 2024). "Does alcohol + rap music = an investment case?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Aaron, Charles (March 9, 2022). "The 50 Best Notorious B.I.G. Songs". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 25, 2024. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c Coker 2003, p. 81.

- ^ a b Eustice, Kyle (September 6, 2019). "The Notorious B.I.G. Wins "Party & Bullshit" Lawsuit". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Michel, Sia (May 1997). "Last Exit from Brooklyn". Spin. Vol. 13, no. 2. New York. p. 69. Archived from the original on March 23, 2024. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Cunningham, Jonathan (December 15, 2004). "Rap pioneer". Detroit Metro Times. Archived from the original on March 23, 2024. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b Diep, Eric (June 29, 2013). "Today In Hip-Hop: The Notorious B.I.G.'s "Party And Bullshit" Released 20 Years Ago". XXL. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Barber, Andrew (May 20, 2022). "The 50 Best Notorious B.I.G. Songs". Complex. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Michel 2005, p. 219.

- ^ a b Coker 2003, p. 305.

- ^ a b Westlake, Wyatt (July 3, 2023). "The Notorious B.I.G.'s Debut Single "Party & Bullsh*t" Turns 30". HotNewHipHop. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Draper 2012, p. 226.

- ^ Breihan 2022.

- ^ Fernando, S. H. Jr. (June 1, 1995). "The B.I.G. Payback". Rolling Stone. No. 709. p. 24. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Dennis, Reginald C. (May 1993). "Record Report: Who's the Man? Soundtrack". The Source. No. 44. New York. pp. 69–70.

- ^ D., Spence (January 17, 2009). "Notorious – Music Inspired By The Motion Picture". IGN. Archived from the original on March 16, 2024. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Eshun, Ekow (June 25, 2005). "Heroes & Villains: Ekow Eshun on Notorious B.I.G." The Independent. London. p. 70. Archived from the original on March 24, 2024. Retrieved March 24, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ro 2001, p. 167.

- ^ Greene, Jayson (March 9, 2017). "The Notorious B.I.G.: Born Again". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Herzog, Kenneth. "Remixes, Vol. 2 – Ratatat". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Lilah, Rose (October 31, 2013). "Party N Bullshit". HotNewHipHop. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "The 25 Best Mash-Ups". Complex. September 27, 2012. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Gonik, Michael (November 15, 2013). "Notorious B.I.G. - "Hypnotize" [Led Zeppelin Remix] + Rare UK TV Diary Ca. 1995". Okayplayer. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Vincent, James (December 7, 2015). "Star Wars mashed with Biggie Smalls has a force all its own". The Verge. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Katz, Jessie (December 7, 2015). "'Star Wars' and Notorious B.I.G. Join Forces in Epic Mash-Up". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "Playlist". Spin. Vol. 19, no. 11. November 2003. p. 115. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ani, Ivie (March 12, 2018). "The Last Poets Copyright Lawsuit Against The Notorious B.I.G. Estate Has Been Dismissed". Okayplayer. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Rys, Dan (March 9, 2018). "Copyright Lawsuit Against Rita Ora, Notorious B.I.G. Estate Dismissed". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Claudia (September 5, 2019). "'Party and Bulls–t': NY Judge Rules Phrase Is Fair Use in Notorious B.I.G., Rita Ora Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ BIG (1993). Party and Bullshit (liner notes). Uptown Records. UPT12 54686.

- ^ a b BIG (1993). Party and Bullshit (liner notes). Uptown Records. UPT8P 2605.

Works cited

[edit]- Abrams, Jonathan (2022). "Chapter 19: That Stuck with Me". The Come Up: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip-Hop. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-9848-2514-8.

- Breihan, Tom (2022). "Chapter 15: Puff Daddy – "Can't Nobody Hold Me Down" (Featuring Mase)". The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal the History of Pop Music. New York: Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-306-82655-9.

- Coker, Cheo Hodari (2003). Unbelievable: The Life, Death, and Afterlife of the Notorious B.I.G.. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80835-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Draper, Jason (2012). "The Notorious B.I.G.". Only the Good Die Young: Robert Johnson, Brian Jones & Amy Winehouse: The Rollercoaster Ride of Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide. London: Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85775-394-6 – via Internet Archive.

- Michel, Sia (2005). "The Notorious B.I.G. – The life and death of Big Poppa". In Hermes, Will (ed.). Spin: 20 Years of Alternative Music: Original Writing on Rock, Hip-Hop, Techno, and Beyond. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-307-23662-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Ro, Ronin (2001). Bad Boy: The Influence of Sean "Puffy" Combs on the Music Industry. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-7434-2823-4 – via Internet Archive.

External links

[edit]- "Party and Bullshit" at Discogs (list of releases)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch