Prehistory

| Part of a series on |

| Human history and prehistory |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future (Holocene epoch) |

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history,[1] is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins c. 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of symbols, marks, and images appears very early among humans, but the earliest known writing systems appeared c. 5,200 years ago. It took thousands of years for writing systems to be widely adopted, with writing having spread to almost all cultures by the 19th century. The end of prehistory therefore came at different times in different places, and the term is less often used in discussing societies where prehistory ended relatively recently.

In the early Bronze Age, Sumer in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley Civilisation, and ancient Egypt were the first civilizations to develop their own scripts and keep historical records, with their neighbours following. Most other civilizations reached their end of prehistory during the following Iron Age. The three-age division of prehistory into Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age remains in use for much of Eurasia and North Africa, but is not generally used in those parts of the world where the working of hard metals arrived abruptly from contact with Eurasian cultures, such as Oceania, Australasia, much of Sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of the Americas. With some exceptions in pre-Columbian civilizations in the Americas, these areas did not develop complex writing systems before the arrival of Eurasians, so their prehistory reaches into relatively recent periods; for example, 1788 is usually taken as the end of the prehistory of Australia.

The period when a culture is written about by others, but has not developed its own writing system, is often known as the protohistory of the culture. By definition,[2] there are no written records from human prehistory, which can only be known from material archaeological and anthropological evidence: prehistoric materials and human remains. These were at first understood by the collection of folklore and by analogy with pre-literate societies observed in modern times. The key step to understanding prehistoric evidence is dating, and reliable dating techniques have developed steadily since the nineteenth century.[3] The most common of these dating techniques is radiocarbon dating.[4] Further evidence has come from the reconstruction of ancient spoken languages. More recent techniques include forensic chemical analysis to reveal the use and provenance of materials, and genetic analysis of bones to determine kinship and physical characteristics of prehistoric peoples.

Definition

Beginning and end

The beginning of prehistory is normally taken to be marked by human-like beings appearing on Earth.[5][6] The date marking its end is typically defined as the advent of the contemporary written historical record.[7][8]

Both dates consequently vary widely from region to region. For example, in European regions, prehistory cannot begin before c. 1.3 million years ago, which is when the first signs of human presence have been found; however, Africa and Asia contain sites dated as early as c. 2.5 and 1.8 million years ago, respectively.[9] Depending on the date when relevant records become a useful academic resource,[10] its end date also varies. For example, in Egypt it is generally accepted that prehistory ended around 3100 BCE, whereas in New Guinea the end of the prehistoric era is set much more recently, in the 1870s, when the Russian anthropologist Nicholai Miklukho-Maklai spent several years living among native peoples, and described their way of life in a comprehensive treatise. In Europe the relatively well-documented classical cultures of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome had neighbouring cultures, including the Celts[11] and the Etruscans, with little writing.[12] Historians debate how much weight to give to the sometimes biased accounts in Greek and Roman literature, of these protohistoric cultures.[11]

Time periods

In dividing up human prehistory in Eurasia, historians typically use the three-age system, whereas scholars of pre-human time periods typically use the well-defined geologic record and its internationally defined stratum base within the geologic time scale. The three-age system is the periodization of human prehistory into three consecutive time periods, named for their predominant tool-making technologies: Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age.[13] In some areas, there is also a transition period between Stone Age and Bronze Age, the Chalcolithic or Copper Age.[14]

For the prehistory of the Americas see Pre-Columbian era.

History of the term

The notion of "prehistory" emerged during the Enlightenment in the work of antiquarians who used the word "primitive" to describe societies that existed before written records.[15] The word "prehistory" first appeared in English in 1836 in the Foreign Quarterly Review.[16]

The geologic time scale for pre-human time periods, and the three-age system for human prehistory, were systematised during the nineteenth century in the work of British, French, German, and Scandinavian anthropologists, archaeologists, and antiquarians.[17][13]

Means of research

The main source of information for prehistory is archaeology (a branch of anthropology), but some scholars are beginning to make more use of evidence from the natural and social sciences.[18][19][20]

The primary researchers into human prehistory are archaeologists and physical anthropologists who use excavation, geologic and geographic surveys, and other scientific analysis to reveal and interpret the nature and behavior of pre-literate and non-literate peoples.[6] Human population geneticists and historical linguists are also providing valuable insight.[5] Cultural anthropologists help provide context for societal interactions, by which objects of human origin pass among people, allowing an analysis of any article that arises in a human prehistoric context.[5] Therefore, data about prehistory is provided by a wide variety of natural and social sciences, such as anthropology, archaeology, archaeoastronomy, comparative linguistics, biology, geology, molecular genetics, paleontology, palynology, physical anthropology, and many others.

Human prehistory differs from history not only in terms of its chronology, but in the way it deals with the activities of archaeological cultures rather than named nations or individuals. Restricted to material processes, remains, and artefacts rather than written records, prehistory is anonymous. Because of this, reference terms that prehistorians use, such as "Neanderthal" or "Iron Age", are modern labels with definitions sometimes subject to debate.

Stone Age

The concept of a "Stone Age" is found useful in the archaeology of most of the world, although in the archaeology of the Americas it is called by different names and begins with a Lithic stage, or sometimes Paleo-Indian. The sub-divisions described below are used for Eurasia, and not consistently across the whole area.

Palaeolithic

"Palaeolithic" means "Old Stone Age", and begins with the first use of stone tools. The Paleolithic is the earliest period of the Stone Age. It extends from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominins c. 3.3 million years ago, to the end of the Pleistocene c. 11,650 BP (before the present period).[21]

The early part of the Palaeolithic is called the Lower Paleolithic (as in excavations it appears underneath the Upper Paleolithic), beginning with the earliest stone tools dated to around 3.3 million years ago at the Lomekwi site in Kenya.[22] These tools predate the genus Homo and were probably used by Kenyanthropus.[23] Evidence of control of fire by early hominins during the Lower Palaeolithic Era is uncertain and has at best limited scholarly support. The most widely accepted claim is that H. erectus or H. ergaster made fires between 790,000 and 690,000 BP in a site at Bnot Ya'akov Bridge, Israel. The use of fire enabled early humans to cook food, provide warmth, have a light source, deter animals at night and meditate.[24][25]

Early Homo sapiens originated some 300,000 years ago,[26] ushering in the Middle Palaeolithic. Anatomic changes indicating modern language capacity also arise during the Middle Palaeolithic.[27] During the Middle Palaeolithic Era, there is the first definitive evidence of human use of fire. Sites in Zambia have charred logs, charcoal and carbonized plants, that have been dated to 180,000 BP.[28] The systematic burial of the dead, music, prehistoric art, and the use of increasingly sophisticated multi-part tools are highlights of the Middle Paleolithic.

The Upper Paleolithic extends from 50,000 and 12,000 years ago, with the first organized settlements and blossoming of artistic work.

Throughout the Palaeolithic, humans generally lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Hunter-gatherer societies tended to be very small and egalitarian,[29] although hunter-gatherer societies with abundant resources or advanced food-storage techniques sometimes developed sedentary lifestyles with complex social structures such as chiefdoms,[30] and social stratification. Long-distance contacts may have been established, as in the case of Indigenous Australian "highways" known as songlines.[31]

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age (from the Greek mesos, 'middle', and lithos, 'stone'), was a period in the development of human technology between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic.

The Mesolithic period began with the retreat of glaciers at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, some 10,000 BP, and ended with the introduction of agriculture, the date of which varied by geographic region. In some areas, such as the Near East, agriculture was already underway by the end of the Pleistocene, and there the Mesolithic is short and poorly defined. In areas with limited glacial impact, the term "Epipalaeolithic" is preferred.[32]

Regions that experienced greater environmental effects as the last ice age ended have a much more evident Mesolithic era, lasting millennia. In Northern Europe, societies were able to live well on rich food supplies from the marshlands fostered by the warmer climate. Such conditions produced distinctive human behaviours that are preserved in the material record, such as the Maglemosian and Azilian cultures. These conditions also delayed the coming of the Neolithic until as late as 4000 BCE (6,000 BP) in northern Europe.

Remains from this period are few and far between, often limited to middens. In forested areas, the first signs of deforestation have been found, although this would only begin in earnest during the Neolithic, when more space was needed for agriculture.

The Mesolithic is characterized in most areas by small composite flint tools: microliths and microburins. Fishing tackle, stone adzes, and wooden objects such as canoes and bows have been found at some sites. These technologies first occur in Africa, associated with the Azilian cultures, before spreading to Europe through the Iberomaurusian culture of Northern Africa and the Kebaran culture of the Levant. However, independent discovery is not ruled out.

Neolithic

"Neolithic" means "New Stone Age", from about 10,200 BCE in some parts of the Middle East, but later in other parts of the world,[34] and ended between 4,500 and 2,000 BCE. Although there were several species of humans during the Paleolithic, by the Neolithic only Homo sapiens sapiens remained.[35] This was a period of technological and social developments which established most of the basic elements of historical cultures, such as the domestication of crops and animals, and the establishment of permanent settlements and early chiefdoms. The era commenced with the beginning of farming, which produced the "Neolithic Revolution". It ended when metal tools became widespread (in the Copper Age or Bronze Age; or, in some geographical regions, in the Iron Age). The term Neolithic is commonly used in the Old World; its application to cultures in the Americas and Oceania is complicated by the fact standard progression from stone to metal tools, as seen in the Old World, does not neatly apply.[36]

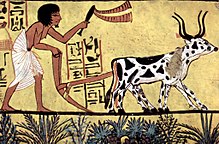

Early Neolithic farming was limited to a narrow range of plants, both wild and domesticated, which included einkorn wheat, millet and spelt, and the keeping of dogs, sheep, and goats. By about 6,900–6,400 BCE, it included domesticated cattle and pigs, the establishment of permanently or seasonally inhabited settlements, and the use of pottery. The Neolithic period saw the development of early villages, agriculture, animal domestication, tools, and the onset of the earliest recorded incidents of warfare.[37]

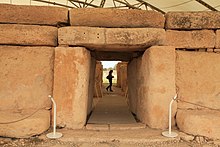

Settlements became more permanent, some with circular houses made of mudbrick with a single room. Settlements might have a surrounding stone wall to keep domesticated animals in and hostile tribes out. Later settlements have rectangular mud-brick houses where the family lived in single or multiple rooms. Burial findings suggest an ancestor cult with preserved skulls of the dead. The Vinča culture may have created the earliest system of writing.[38] The megalithic temple complexes of Ġgantija are notable for their gigantic structures. Although some late Eurasian Neolithic societies formed complex stratified chiefdoms or even states, states evolved in Eurasia only with the rise of metallurgy, and most Neolithic societies on the whole were relatively simple and egalitarian.[39] Most clothing appears to have been made of animal skins, as indicated by finds of large numbers of bone and antler pins which are ideal for fastening leather. Wool cloth and linen might have become available during the later Neolithic,[40][41] as suggested by finds of perforated stones that (depending on size) may have served as spindle whorls or loom weights.[42][43][44]

Chalcolithic

In Old World archaeology, the "Chalcolithic", "Eneolithic", or "Copper Age" refers to a transitional period where early copper metallurgy appeared alongside the widespread use of stone tools. During this period, some weapons and tools were made of copper. This period was still largely Neolithic in character. It is a phase of the Bronze Age before it was discovered that adding tin to copper formed the harder bronze. The Copper Age is seen as a transition period between the Stone Age and Bronze Age.[45]

An archaeological site in Serbia contains the oldest securely dated evidence of copper making at high temperature, from 7,500 years ago. The find in 2010 extends the known record of copper smelting by about 800 years, and suggests that copper smelting may have been invented independently in separate parts of Asia and Europe at that time, rather than spreading from a single source.[46] The emergence of metallurgy may have occurred first in the Fertile Crescent, where it gave rise to the Bronze Age in the 4th millennium BCE (the traditional view), although finds from the Vinča culture in Europe have now been securely dated to slightly earlier than those of the Fertile Crescent. Timna Valley contains evidence of copper mining 7,000 years ago.[47] The process of transition from Neolithic to Chalcolithic in the Middle East is characterized in archaeological stone tool assemblages by a decline in high quality raw material procurement and use. North Africa and the Nile Valley imported its iron technology from the Near East and followed the Near Eastern course of Bronze Age and Iron Age development.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is the earliest period in which some civilizations reached the end of prehistory, by introducing written records. The Bronze Age, or parts thereof, are thus considered to be part of prehistory only for the regions and civilizations who developed a system of keeping written records during later periods. The invention of writing coincides in some areas with the beginnings of the Bronze Age. After the appearance of writing, people started creating texts including written records of administrative matters.[48]

The Bronze Age refers to a period in human cultural development when the most advanced metalworking (at least in systematic and widespread use) included techniques for smelting copper and tin from naturally occurring outcroppings of ores, and then combining them to cast bronze. These naturally occurring ores typically included arsenic as a common impurity. Tin ores are rare, as reflected in the fact there were no tin bronzes in Western Asia before 3000 BCE. The Bronze Age forms part of the three-age system for prehistoric societies.[49] In this system, it follows the Neolithic in some areas of the world.

While copper is a common ore, deposits of tin are rare in the Old World, and often had to be traded or carried considerable distances from the few mines, stimulating the creation of extensive trading routes. In many areas as far apart as China and England, the valuable new material was used for weapons, but for a long time apparently not available for agricultural tools. Much of it seems to have been hoarded by social elites, and sometimes deposited in extravagant quantities, from Chinese ritual bronzes and Indian copper hoards, to European hoards of unused axe-heads.

By the end of the Bronze Age large states, whose armies imposed themselves on people with a different culture, and are often called empires, had arisen in Egypt, China, Anatolia (the Hittites), and Mesopotamia, all of them literate.

Iron Age

The Iron Age is not part of prehistory for all civilizations who had introduced written records during the Bronze Age. Most remaining civilizations did so during the Iron Age, often through conquest by empires, which continued to expand during this period. For example, in most of Europe conquest by the Roman Empire means the term Iron Age is replaced by "Roman", "Gallo-Roman", and similar terms after the conquest. Even before conquest, many areas began to have a protohistory, as they were written about by literate cultures; the protohistory of Ireland is an example.

In archaeology, the Iron Age refers to the advent of ferrous metallurgy. The adoption of iron coincided with other changes, often including more sophisticated agricultural practices, religious beliefs and artistic styles, which makes the archaeological Iron Age coincide with the "Axial Age" in the history of philosophy. Although iron ore is common, the metalworking techniques necessary to use iron are different from those needed for the metal used earlier, more heat is required.[50] Once the technical challenge had been solved, iron replaced bronze as its higher abundance meant armies could be armed much more easily with iron weapons.[51]

Timeline

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All dates are approximate and conjectural, obtained through research in the fields of anthropology, archaeology, genetics, geology, or linguistics. They are all subject to revision due to new discoveries or improved calculations. BP stands for "Before Present (1950)." BCE stands for "Before Common Era".

Paleolithic

- c. 3.3 million BP – Earliest stone tools[22]

- c. 2.8 million BP – Genus Homo appears

- c. 600,000 BP – Hunting-gathering

- c. 400,000 BP – Control of fire by early humans

- c. 300,000 BP – Anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) appear in Africa,[26] one of whose characteristics is a lack of significant body hair compared to other primates. See Jebel Irhoud.

- c. 300,000–30,000 BP – Mousterian (Neanderthal) culture in Europe.[52]

- c. 170,000–83,000 BP – Invention of clothing[53]

- c. 75,000 BP – Toba Volcano supereruption.[54]

- c. 80,000–50,000 BP – Homo sapiens exit Africa as a single population.[55][56] In the next millennia, descendants from this population migrate to southern India, the Malay islands, Australia, Japan, China, Siberia, Alaska, and the northwestern coast of North America.[56]

- c. 80,000–50,000? BP – Behavioral modernity, by this point including language and sophisticated cognition

- c. 45,000 BP / 43,000 BCE – Beginnings of Châtelperronian culture in France.

- c. 40,000 BP / 38,000 BCE – First human settlement in the southern half of the Australian mainland, by indigenous Australians (including the future sites of Sydney,[57][58] Perth,[59] and Melbourne.[60])

- c. 32,000 BP / 30,000 BCE – Beginnings of Aurignacian culture, exemplified by the cave paintings ("parietal art") of Chauvet Cave in France.

- c. 30,500 BP / 28,500 BCE – New Guinea is populated by colonists from Asia or Australia.[61]

- c. 30,000 BP / 28,000 BCE – A herd of reindeer is slaughtered and butchered by humans in the Vezere Valley in what is today France.[62]

- c. 28,000–20,000 BP – Gravettian period in Europe. Harpoons, needles, and saws invented.

- c. 26,500 BP – Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Subsequently, the ice melts and the glaciers retreat again (Late Glacial Maximum). During this latter period human beings return to Western Europe (see Magdalenian culture) and enter North America from Eastern Siberia for the first time (see Paleo-Indians, pre-Clovis culture and Settlement of the Americas).

- c. 26,000 BP / 24,000 BCE – People around the world use fibres to make baby-carriers, clothes, bags, baskets, and nets.[63]

- c. 25,000 BP / 23,000 BCE – A settlement consisting of huts built of rocks and mammoth bones is founded near what is now Dolní Věstonice in Moravia in the Czech Republic. This is the oldest human permanent settlement that has been found by archaeologists.[64]

- c. 23,000 BP / 21,000 BCE – Small-scale trial cultivation of plants in Ohalo II, a hunter-gatherers' sedentary camp on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel.[65]

- c. 16,000 BP / 14,000 BCE – Wisent (bison) sculpted in clay deep inside the cave now known as Le Tuc d'Audoubert in the French Pyrenees near what is now the border of Spain.[66]

- c. 14,800 BP / 12,800 BCE – The Humid Period begins in North Africa. The region that would later become the Sahara is wet and fertile, and the aquifers are full.[67]

Mesolithic/Epipaleolithic

- c. 12,500 to 9,500 BCE – Natufian culture: a culture of sedentary hunter-gatherers who may have cultivated rye in the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean)

Neolithic

- c. 9,400–9,200 BCE – Figs of a parthenocarpic (and therefore sterile) type are cultivated in the early Neolithic village Gilgal I (in the Jordan Valley, 13 km north of Jericho). The find predates the domestication of wheat, barley, and legumes, and may thus be the first known instance of agriculture.[68][69][70]

- c. 9,000 BCE – Circles of T-shaped stone pillars erected at Göbekli Tepe in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey during pre-pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) period. As yet unexcavated structures at the site are thought to date back to the epipaleolithic.

- c. 8,000 BCE / 7000 BCE – In northern Mesopotamia, now northern Iraq, cultivation of barley and wheat begins. At first they are used for beer, gruel, and soup, eventually for bread.[71] In early agriculture at this time the planting stick is used, but it is replaced by a primitive plough in subsequent centuries.[72] Around this time, a round stone tower, now preserved at about 8.5 meters high and 8.5 meters in diameter is built in Jericho.[73]

Chalcolithic

- c. 3,700 BCE – Pictographic proto-writing, known as proto-cuneiform, appears in Sumer, and records begin to be kept. According to the majority of specialists, the first Mesopotamian writing (actually still pictographic proto-writing at this stage) was a tool for record-keeping that had little connection to the spoken language.[74]

- c. 3,300 BCE – Approximate date of death of "Ötzi the Iceman", found preserved in ice in the Ötztal Alps in 1991. A copper-bladed axe, which is a characteristic technology of this era, was found with the corpse.

- c. 3,100 BCE – Skara Brae is constructed. This stone-built village consisted of ten clustered houses with stone hearths, beds, cupboards, and an ancient sewer system. This village occupied for 600 years before being abandoned in c. 2,500 BCE.

- c. 3,000 BCE – Stonehenge construction begins. In its first version, it consisted of a circular ditch and bank, with 56 wooden posts.[75]

- c. 3,000 BCE – The Yamnaya expansions from the Pontic–Caspian steppe into Europe and Asia. These migrations are thought to have spread Yamnaya Steppe pastoralist ancestry and Indo-European languages across large parts of Eurasia.[76]

By region

- Old World

- Prehistoric Africa

- Prehistoric Asia

- East Asia:

- South Asia

- Prehistory of Central Asia

- Prehistoric Siberia

- Southeast Asia:

- Southwest Asia (Near East)

- Prehistoric Europe

- New World

- Pre-Columbian Americas

- Oceania

See also

References

- ^ McCall, Daniel F.; Struever, Stuart; Van Der Merwe, Nicolaas J.; Roe, Derek (1973). "Prehistory as a Kind of History". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 3 (4): 733–739. doi:10.2307/202691. JSTOR 202691.

- ^ "Dictionary Entry". Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Graslund, Bo. 1987. The birth of prehistoric chronology. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "What is Carbon Dating? | University of Chicago News". news.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Renfrew, Colin. 2008. Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind. New York: Modern Library

- ^ a b Fagan, Brian. (2007). World Prehistory: A brief introduction New York: Prentice-Hall, (Seventh ed.), Chapter One

- ^ Fagan, Brian (2017). World Prehistory: A brief introduction (Ninth ed.). London: Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-317-27910-5. OCLC 958480847.

- ^ Forsythe, Gary (2005). A critical history of early Rome : from prehistory to the first Punic War. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-520-94029-1. OCLC 70728478.

- ^ Menéndez, Mario (2019). Prehistoria de la Península Ibérica: el progreso de la cognición, el mestizaje y las desigualdades durante más de un millón de años (in European Spanish). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. p. 25. ISBN 978-84-9181-602-7. OCLC 1120111673.

- ^ Connah, Graham (11 May 2007). "Historical Archaeology in Africa: An Appropriate Concept?". African Archaeological Review. 24 (1–2): 35–40. doi:10.1007/s10437-007-9014-9. ISSN 0263-0338. S2CID 161120240.

- ^ a b "Viewing the Ancient Celts through the Lens of Greece and Rome". GHD. 9 February 2021.

- ^ Huntsman, Authors: Theresa. "Etruscan Language and Inscriptions | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

- ^ a b Eddy, Matthew Daniel, ed. (2011). Prehistoric Minds: Human Origins as a Cultural Artefact. Royal Society of London. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "Chalcolithic | British Museum". Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2011). "The Line of Reason: Hugh Blair, Spatiality and the Progressive Structure of Language". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 65: 9–24. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2010.0098. S2CID 190700715. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2011). "The Prehistoric Mind as a Historical Artefact". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 65: 1–8. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2010.0097. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Geroulanos, Stefanos (2024). "Chapter 4: Humanity, Divided by Three". The Invention of Prehistory: Empire, Violence, and Our Obsession with Human Origins. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. 63–72. ISBN 978-1-324-09145-5. OCLC 1379265149.

- ^ The Prehistory of Iberia: Debating Early Social Stratification and the State edited by María Cruz Berrocal, Leonardo García Sanjuán, Antonio Gilman. Pg 36.

- ^ Historical Archaeology: Back from the Edge. Edited by Pedro Paulo A. Funari, Martin Hall, Sian Jones. p. 8.ISBN 9780415518888

- ^ Through the Ages in Palestinian Archaeology: An Introductory Handbook. By Walter E. Ras. p. 49.ISBN 9781563380556

- ^ Toth, Nicholas; Schick, Kathy (2007). "Overview of Paleolithic Anthropology". In Henke, H. C. Winfried; Hardt, Thorolf; Tatersall, Ian (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Vol. 3. Berlin; Heidelberg; New York: Springer. pp. 1943–1963. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_64. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4.

- ^ a b Harmand, Sonia; et al. (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–315. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..310H. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961. S2CID 1207285. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Harmand et al., 2015, p. 315.

- ^ "How Early Humans Shaped the World With Fire". SAPIENS. 28 May 2021.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian. "Fire Good. Make Human Inspiration Happen". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ a b Hublin JJ, Ben-Ncer A, Bailey SE, Freidline SE, Neubauer S, Skinner MM, et al. (June 2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953. S2CID 256771372. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Race and Human Evolution. By Milford H. Wolpoff. p. 348.

- ^ James, Steven R. (February 1989). "Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 30 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1086/203705. S2CID 146473957. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Vanishing Voices : The Extinction of the World's Languages. By Daniel Nettle, Suzanne Romaine Merton Professor of English Language University of Oxford. pp. 102–103.

- ^ Earle, Timothy (1989). "Chiefdoms". Current Anthropology. 30 (1): 84–88. doi:10.1086/203717. JSTOR 2743311. S2CID 145014800.

- ^ "Songlines: the Indigenous memory code". Radio National. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ "Epipalaeolithic". glosbe.com.

- ^ "Hagarqim « Heritage Malta". Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies by Peter Bellwood, 2004

- ^ "World Museum of Man: Neolithic / Chalcolithic Period". World Museum of Man. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ "Stone Age - Prehistoric Americas, Tools, Artifacts | Britannica".

- ^ Price, TD; Wahl, J; Bentley, RA (2006). "Isotopic evidence for mobility and group organization among Neolithic farmers at Talheim, Germany, 5000 BC". European Journal of Archaeology. 9 (2–3): 259–284. doi:10.1177/1461957107086126. S2CID 162580508.

- ^ Winn, Shan (1981). Pre-writing in Southeastern Europe: The Sign System of the Vinča Culture ca. 4000 BC. Calgary: Western Publishers.

- ^ Leonard D. Katz Rigby; S. Stephen Henry Rigby (2000). Evolutionary Origins of Morality: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives. United kingdom: Imprint Academic. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7190-5612-3. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Harris, Susanna (2009). "Smooth and Cool, or Warm and Soft: Investigatingthe Properties of Cloth in Prehistory". North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles X. Academia.edu. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "Aspects of Life During the Neolithic Period" (PDF). Teachers' Curriculum Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Gibbs, Kevin T. (2006). "Pierced clay disks and Late Neolithic textile production". Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Academia.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Green, Jean M (1993). "Unraveling the Enigma of the Bi: The Spindle Whorl as the Model of the Ritual Disk". Asian Perspectives. 32 (1): 105–124. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015.

- ^ Cook, M (2007). "The clay loom weight, in: Early Neolithic ritual activity, Bronze Age occupation and medieval activity at Pitlethie Road, Leuchars, Fife". Tayside and Fife Archaeological Journal. 13: 1–23.

- ^ Sasha Blakeley; Christopher Muscato (2023). "Copper Age / Chalcolithic Age". Study.com.

- ^ "Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers". ScienceNews. 17 July 2010. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Timna". Biblical Archaeology – Maps and Findings.

- ^ "The University of Chicago Magazine: Features". magazine.uchicago.edu.

- ^ "Three-age system | archaeology | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- ^ "Bronze and Iron: A Comparison · Extended Artefact Features · Museum of Classical Antiquities, University of Ottawa". omeka.uottawa.ca.

- ^ "Why Did it Take So Long Between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age? | MATSE 81: Materials In Today's World". www.e-education.psu.edu.

- ^ Shea, J.J. (2003). "Neanderthals, competition and the origin of modern human behaviour in the Levant". Evolutionary Anthropology. 12 (4): 173–187. doi:10.1002/evan.10101. S2CID 86608040.

- ^ Toups, M.A.; Kitchen, A.; Light, J.E.; Reed, D. L. (September 2010). "Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq234. PMC 3002236. PMID 20823373. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017.

- ^ Jones, Tim (6 July 2007). "Mount Toba Eruption – Ancient Humans Unscathed, Study Claims". Anthropology.net. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (21 September 2016). "How We Got Here: DNA Points to a Single Migration From Africa". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ a b This is indicated by the M130 marker in the Y chromosome. "Traces of a Distant Past", by Gary Stix, Scientific American, July 2008, pp. 56–63.

- ^ Macey, Richard (2007). "Settlers' history rewritten: go back 30,000 years". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Aboriginal people and place". Sydney Barani. 2013. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Sandra Bowdler. "The Pleistocene Pacific". Published in 'Human settlement', in D. Denoon (ed) The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders. pp. 41–50. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. University of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Gary Presland, The First Residents of Melbourne's Western Region, (revised edition), Harriland Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-646-33150-8. Presland says on p. 1: "There is some evidence to show that people were living in the Maribyrnong River valley, near present day Keilor, about 40,000 years ago."

- ^ James Trager, The People's Chronology, 1994, ISBN 978-0-8050-3134-8

- ^ Gene S. Stuart, "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages." In Mysteries of the Ancient World, a publication of the National Geographic Society, 1979. pp. 11–18.

- ^ "Venus of Willendorf". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Stuart, Gene S. (1979). "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages". Mysteries of the Ancient World. National Geographic Society. p. 19.

- ^ Snir, Ainit (2015). "The Origin of Cultivation and Proto-Weeds, Long Before Neolithic Farming". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0131422. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1031422S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131422. PMC 4511808. PMID 26200895.

- ^ Stuart, Gene S. (1979). "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages". Mysteries of the Ancient World. National Geographic Society. pp. 8–10.

- ^ "Shift from Savannah to Sahara was Gradual", by Kenneth Chang, New York Times, 9 May 2008.

- ^ Kislev, M. E.; Hartmann, A.; Bar-Yosef, O. (2006a). "Early Domesticated Fig in the Jordan Valley". Science. 312 (5778). Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1372–1374. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1372K. doi:10.1126/science.1125910. PMID 16741119. S2CID 42150441.

- ^ Kislev, M. E.; Hartmann, A.; Bar-Yosef, O. (2006b). "Response to Comment on "Early Domesticated Fig in the Jordan Valley"". Science. 314 (5806). Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1683b. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1683K. doi:10.1126/science.1133748. PMID 17170278.

- ^ Lev-Yadun, S.; Ne'Eman, G.; Abbo, S.; Flaishman, M. A. (2006). "Comment on "Early Domesticated Fig in the Jordan Valley"". Science. 314 (5806). Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1683a. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1683L. doi:10.1126/science.1132636. PMID 17170278.

- ^ Kiple, Kenneth F. and Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè, eds., The Cambridge World History of Food, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 83

- ^ "No-Till: The Quiet Revolution", by David Huggins and John Reganold, Scientific American, July 2008, pp. 70–77.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M, ed. The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1996 ISBN 978-0-521-40216-3, p. 363.

- ^ Glassner, Jean-Jacques. The Invention of Cuneiform: Writing In Sumer. Trans. Zainab Bahrani. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Ebook.

- ^ Caroline Alexander, "Stonehenge", National Geographic, June 2008.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (August 2019). "The first Europeans weren't who you might think". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

External links

- Submerged Landscapes Archaeological Network

- North Pacific Prehistory is an academic journal specialising in Northeast Asian and North American archaeology.

- Prehistory in Algeria and in Morocco

- Early Humans a collection of resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch