Ratcliffe Manor

| Ratcliffe Manor | |

|---|---|

Ratcliffe Manor from the river side in 1936 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| Address | 7768 Ratcliffe Manor Road |

| Town or city | Easton, Maryland |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 38°45′44.4″N 76°06′40.0″W / 38.762333°N 76.111111°W |

| Construction started | 1757 |

| Completed | 1762 |

| Client | Henry Hollyday |

| Owner | privately owned |

Ratcliffe Manor, occasionally misspelled as "Radcliffe Manor", is a Georgian colonial home in Maryland completed around 1762 by Henry Hollyday. It gets its name from the "Mannour of Ratcliffe", which is one of the Maryland Eastern Shore's oldest land grants. The dwelling is considered one of the most distinctive plantation houses on the Eastern Shore, with a northeast facade on the land approach side and a nearly identical southwest facade on the river approach side. The entire property is included in the Maryland Historical Trust's Inventory of Historic Properties. A set of photographs of the estate, made in the 1930s and 1940s, is part of the Historic American Buildings Survey administered by the Library of Congress and National Park Service.

The estate is located on the Tred Avon River in Talbot County near Easton, Maryland. During the War of 1812, a fort consisting of a six–gun artillery battery was constructed on Ratcliffe Manor property to protect the town of Easton from a river approach by British soldiers. Although Easton was not attacked, British troops landed further west in the county at least twice, fighting in small battles that became known as the Battle of St. Michaels and Second Battle of St. Michaels.

The Hollyday family occupied the manor house for about 140 years. Former residents of the manor house include Richard C. Hollyday, secretary of State of Maryland; and Charles Hopper Gibson, a United States Senator. During the first half of the 20th century, Ratcliffe Manor was an agricultural and dairy complex. It was sold to diplomat Gerard C. Smith and his wife in 1945, and they restored the house and its grounds. The Smith family members began selling portions of the property in 1995. By the end of the century, plans were made to sell a portion of the manor grounds for development. Today, the privately owned plantation house still stands, separated by a wooded area from a planned community called Easton Village.

Beginning

[edit]Ratcliffe Manor is located in Talbot County's town of Easton, Maryland. The property is on a peninsula formed by the Tred Avon River and Dixon Creek.[1][Note 1] Henry Hollyday began accumulating materials for the construction of the Ratcliffe Manor house in 1755, and expected to start building in 1757.[3] Although the exact construction start and finish dates are not available, Hollyday appears to have occupied Ratcliffe Manor by 1762 based on a letter written to his brother.[4] At the time of the manor's construction, Talbot County was part of the English Province of Maryland, and the United States and state of Maryland did not yet exist.[5][6] The house's architect is unknown, but Hollyday had a plan because he knew the layout of the house—including materials needed and their quantities.[4] Bricks used in construction were made on site, and home furnishings were ordered from London.[7] In 1919, evidence could still be found on the property of the hole caused by removing clay to make bricks.[8][Note 2]

The Hollyday farm of the 1760s has been described as "another of the great bayside plantations".[11] Tobacco was the main cash crop on Maryland's Eastern Shore during the 17th and early 18th centuries.[11] Histories of colonial plantations in southern regions such as Virginia tend to focus on tobacco production.[12] However, grain was a more important crop at Ratcliffe Manor than tobacco. On average, the farm produced 3,700 pounds (1,700 kg) of tobacco, 315 bushels (8.6 metric tons) of wheat, 185 barrels of corn, and 55 bushels (1.5 metric tons) of oats. Hollyday used seven fieldhands and a paid overseer to maintain his crops, and hired additional people during harvest time.[11] Hollyday's farm became more productive, and by the time of the American Revolution he owned 60 to 70 slaves.[13] His family grew to 11 people, plus he employed a nurse, weavers, and spinners. He raised cattle, hogs, and sheep. His crops at that time were cotton, hemp, corn, and wheat. Although tobacco was raised in the early years of the farm, this product fell out of favor as the English markets closed.[13]

Architecture

[edit]

The Maryland Historical Trust file on Ratcliffe Manor uses a spelling of "Radcliffe" when discussing the property's 20th century dairy complex, but it uses the "Ratcliffe" spelling elsewhere.[1][Note 3] Ratcliffe Manor is described as "one of the most elaborate and distinctive mid-eighteenth century plantation dwellings erected on Maryland's Eastern Shore."[1] The trust also notes that the manor house "...has had only minor alterations since its original construction and retains the majority of its historic building fabric."[1] Another source mentions that the side of the house that faces the water is nearly identical to the land approach side, which gives the house two façades. While the land approach is highlighted by a long flower and tree-lined driveway, the water approach used to have a terraced boxwood garden between the Tred Avon River and the house.[14][Note 4]

Exterior

[edit]The two–and–a–half-story home was made from Flemish bond red brick, and is the highlight of a plantation that at one time consisted of over 1,000 acres (400 ha).[1] The house's design is typical of the Maryland manor houses of the time, consisting of a main section with a wing. The middle of the main building has a simple portico and doorway.[16] The jerkin-head roof on the main building has four end chimneys.[1] The land approach side of the home is on the northeast side of the structure. This side, which can be considered the front of the main portion of the house, is a symmetrical five-bay elevation with two twelve–over–twelve sash windows adjacent to each side of the door. The second floor has five evenly–spaced twelve-over-eight sash windows. The roof on the front side has three gable roof dormers with round arch sash windows.[1]

Like the front, the rear (southwest) facade of the main building is a balanced five-bay elevation with center entrance, sash windows, and dormers. The rear facade faces the Tred Avon River approach to the house. From the front facade, the exterior wall on the left side of the building has a corner door that leads to the study, and at the opposite corner is a bulkhead entrance to the cellar.[1] The wing is to the right when facing the front of the house. It was originally a one–and–a–half-story three-bay room that included the kitchen. The kitchen was severely damaged by fire in the first half of the 20th century, and reconstruction work was altered in 1953 when the wing was remodeled. The wing was extended further west with a kitchen addition that was made to have the exterior appearance of a "subsidiary outbuilding".[1] A large glassed-in porch was also added in the 20th century, and its entrance is via the wing's south wall.[1]

The long land approach to the house is lined with flowers and trees.[17] The garden, located between the back of the house and the Tred Avon River, has been sophisticated enough that it has been, on multiple occasions, part of the Maryland House and Garden Pilgrimage tour.[18][Note 5] The garden is thought to have been laid out around the same time as the manor house was constructed. It is probable that family members studied Philip Miller's Gardeners Dictionary. Hollyday's mother–in–law, Henrietta Maria Tilghman Robins, quoted Miller in letters written to English naturalist Peter Collinson, who was a friend of her husband George Robins.[22]

Interior

[edit]

A 1992 Maryland Historical Trust report states that the house has "approximately 75% of its original mid-eighteenth century woodwork."[1] The interior of the main building of the house has three rooms on the front (land) side of the house, and two rooms on the back side that overlook the garden and river.[1] The most extravagant room is the parlor, which is located in the back of the house. The parlor's walls consist of raised panel woodwork, and are among the best in Georgian style craftsmanship still found in Talbot County. The room's windows face the Tred Avon River, and the fireplace and surroundings are a fine example of 18th century ornamentation.[1] During the 1700s, the general interior scheme of five rooms on the main floor with the best room in the back of the house, and similar variations, became so common among upscale homes across the bay in Annapolis that it has been called the "Annapolis Plan".[23]

A 1914 description of the house does not use the term "parlor" for either of the two rooms on the river side of the house. Instead, it mentions dining and living rooms. The living room is described as opening upon the terraced garden.[16] An office (or library) is located in the front of the house, and all downstairs rooms are paneled in hardwood. The wing of the house contained the kitchen, pantry, and servant's rooms.[16] The inside of the one–and–a–half-story wing was redone during the 20th century, and a glassed-in porch was added.[1]

Just inside the front entrance interior is a walnut dog-leg stairway with balusters that leads to the second floor.[1] This floor consists of four rooms that connect to the hallway. All four have fireplaces. Originally these rooms were bedrooms, but the northeast "bedroom" has been converted to a bathroom. Another bathroom has been added between the two bedrooms on the south side. Some of these rooms feature chair rails, baseboard moldings, and window seats. A stairway to the attic, consisting of two flights of steps, is located in the northwest corner.[1] The attic section of the house was finished around 1800. It contains three bedrooms that open to a center hallway. The attic rooms have six-panel doors, but these rooms are otherwise plainly finished.[1]

History

[edit]Ratcliffe estate

[edit]

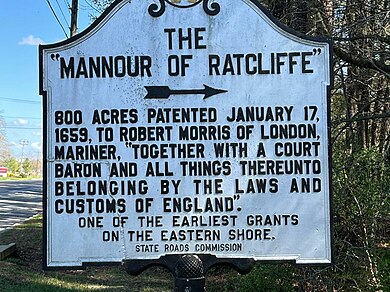

At the time of the land grants in colonial Maryland, an English manor was defined as "a piece of landed property with tenants over whom the landlord exercised rights of jurisdiction in a private court".[24][25] The manor typically had a manor house, and now the term "manor" is also defined as "a residence".[24] Ratcliffe Manor in 1660 refers to a plot of land that became a plantation, while today it refers to a house on a large lot. In colonial Maryland, there were 62 true manors (using the property definition) granted to private citizens between August 1634 and April 1684.[25] Among the 62 manors is Ratcliffe Manor, originally called the Mannour of Ratcliffe on the patent. Ratcliffe Manor was first surveyed for 800 acres (320 ha) on August 5, 1659, and a patent was issued on January 17, 1659/60.[25][Note 6]

The Mannour of Ratcliffe was granted by Lord Baltimore (Cecilius Calvert) to Captain Robert Morris of London.[26] Morris had been sailing to Maryland since at least June 1653. He was from the Ratcliffe area of London, England, which was the home of a shipyard.[27][Note 7] Captain Morris and his wife Martha sold the Ratcliffe property to London physician James Wasse on August 12, 1674.[Note 8] The land was resurveyed in 1675 after an issue with the certificate, and regranted on May 22, 1676—as 920 acres (370 ha).[25] Wasse sold the property to Thomas Bartlett around 1692, and the property later became divided among the Bartlett children.[3][Note 9]

Henry Hollyday

[edit]The builder of Ratcliffe Manor, Henry Hollyday, son of James Hollyday and Sarah Covington Lloyd Hollyday, was born at the Wye Plantation in 1725.[7][Note 10] In the early 1730s, James and Sarah Hollyday built a new home they called Readbourne, which is located in Queen Anne's County on the Chester River.[35] Mrs. Hollyday supervised the construction of this home.[36][Note 11] James Hollyday died in 1747, leaving the property to his eldest son James Hollyday Jr. after the death of Sara—who died later in 1755.[38][39] Readbourne has been part of the National Register of Historic Places since 1973.[39]

In 1748, Henry Hollyday married Anna Maria Robins, who was the daughter of George Robins of Peach Blossom in Talbot County.[Note 12] Anna received land, via the will of her father, that included land called Ratcliffe Manor. Portions of the land had been purchased by George Robins from Thomas Bartlett.[7] Henry and Anna lived in Queen Ann's County until October 1751 when they moved to Talbot County. In 1752, Hollyday purchased from Samuel Bartlett land adjacent to Ratcliffe Manor known as Cool Spring Cove, and this is the location of the Ratcliffe Manor house Hollyday built for his wife.[7] Of the original Ratcliffe Manor estate owned by Captain Robert Morris, Hollyday had pieced together 629 acres (255 ha).[3] Henry and wife Anna had ten children between 1750 and 1774, including three sons that survived to maturity.[40] Henry's childless older brother James died in 1786, leaving his property that included Readbourne to Henry with an agreement that Henry's oldest son James III would inherit the property when Henry died.[41][42]

Henry II

[edit]

Henry lived in the Ratcliffe Manor house for nearly three decades, and died in 1789.[42] Upon his death, eldest son James III officially inherited most of the Readbourne property, including the manor house. Henry's second son, Thomas, received in trust 300 acres (120 ha) at the southern end of the Readbourne property, which was known as Brimmington.[42] Henry's will originally left the Ratcliffe plantation to his wife Anna, with son Thomas inheriting the property after his mother's death. An amendment to the will replaced Thomas with another son, Henry (a.k.a. Henry Hollyday II), because of Thomas' conduct.[43][Note 13]

Henry II, who graduated from Princeton, would live at Ratcliffe Manor for the rest of his life.[45] He married Ann Carmichael on October 11, 1798.[46] His mother Anna died in 1806.[47] Henry Hollyday II and his wife Ann had eleven children. He practiced law and continued the plantation.[Note 14] From 1816 to 1821 he was a representative in the Maryland state senate.[46] His land holdings included property in Queen Anne's County in addition to Talbot County. He died in 1850. The Ratcliffe Manor estate was divided among three surviving sons, while land in Queen Anne's County was divided among his daughters.[46]

Fort Stoakes

[edit]

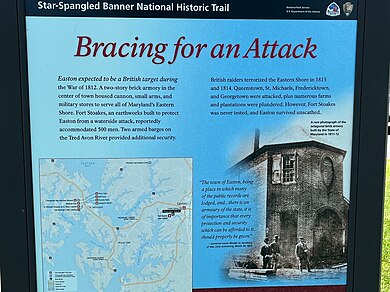

Ratcliffe Manor was the site of a fortress built during the War of 1812.[51][52] Fort Stoakes was located on Ratcliffe Manor property on the Tred Avon River and housed a six-gun (a.k.a. cannons or artillery pieces) battery.[52][53] During the war, residents of Easton worried that the British would invade their town via the Third Haven River (now known as the Tred Avon River).[54][Note 15] Henry Hollyday II, owner of Ratcliffe Manor, was one of the concerned citizens and had been involved with the Eastern Shore Militia as early as 1799.[47] A false alarm involving domestic cargo vessels created more anxiety.[56]

Citizens of the Easton hastily constructed an earthworks named Fort Stoakes. The fort was named after James Stoakes because most of the construction work was conducted by workers from Mr. Stoakes' nearby shipyard.[51] Easton and the fort, occasionally spelled "Stokes" instead of "Stoakes", were never attacked.[53] The British attacked further west in Talbot County near the shipbuilding town of Saint Michaels, and the two small skirmishes became known as the Battle of St. Michaels and the Second Battle of St. Michaels.[57] By the 1940s, all that remained of the fort were "two ditch-like impressions in the earth on the tree-shaded river bank".[58] However, a Fort Stoakes marker provided by the Star-Spangled Banner National Historic Trail is located across the river at a marina on Easton Point.[59]

Last Hollyday

[edit]

Henry II's eldest son Richard Carmichael Hollyday returned to Talbot County when his father died in 1850.[60] Richard selected the portion of his father's land that contained the Ratcliffe Manor house. His brother, Thomas Robins Hollyday, took a portion of land west of the manor house and named it "Lee Haven". The third brother, William Murray Hollyday, took land on the east side of the manor house and named it "Glenwood".[61] Richard Hollyday married Marietta Fauntleroy Powell in 1858 and had three children.[60] Their son Richard Carmichael Hollyday II joined the United States Navy and rose to the rank of rear admiral.[62]

The elder Richard Hollyday was Secretary of State of Maryland under six governors. He resigned from that position in 1884 because of bad health.[60] Upon his death in 1885, his widow Marietta remained living on the property.[1] She married United States Senator Charles Hopper Gibson in 1889, and the couple lived in Ratcliffe Manor.[63][1] Mrs. Gibson published a cookbook in 1894 that included a recipe for "Ratcliffe Manor Sausage" on page 38.[64] The Senator died in 1900, and the family had begun trying to sell the house as early as October 1899.[65][66] By that time, Thomas Robins Hollyday and William Murray Hollyday were dead too.[66] Hollyday ownership of Ratcliffe Manor ended in 1903, when the property was sold to John M. Elliott.[67]

Others

[edit]When John M. Elliott purchased Ratcliffe Manor property in 1903, he promptly resold most of the property to Andrew A. Hathaway of Wisconsin.[67] The property was converted to a dairy farm.[1] Hathaway's two sons, Malcom and Stephen, built two landing strips in a cow pasture near their home in 1928—the county's first airstrip.[68] Their Tred Avon Flying Service was one of Talbot County's early commercial aviation companies.[69] In 1936, the property was sold to John W. McCoy, and consisted of over 300 acres (120 ha) and several miles of waterfront.[70] The dairy operation continued, and the manor house was photographed by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS).[71][Note 16] McCoy was an executive director of the DuPont Corporation.[73]

Diplomat Gerard C. "Gerry" Smith, who was an avid sailor, purchased Ratcliffe Manor in 1945.[74] Smith and his wife restored the interior of the home, and they converted the old kitchen into a dining room.[30] Dairy operations were discontinued after about one year, and Smith purchased an additional home in New York City. Assisting the Smith family in maintaining the Ratcliffe Manor house was the Ayers family, descendants of slaves that lived in another house on the property.[75] The Ayers family managed the Ratcliffe Manor house for multiple generations, making their tenure at Ratcliffe Manor longer than that of the Smith family.[75] Smith died in 1994, while his wife Bernice died in 1987.[76]

Development

[edit]

Smith family members sold the Ratcliffe Manor house and a portion of the property in 1995.[75][1] The house remains a privately owned residence with a private access road named Ratcliffe Manor Road. A small road named Fort Stokes Lane, also private, intersects with Ratcliffe Manor Road and Dixon Creek Lane.[77] The parallel road to the west of Ratcliffe Manor Road is named Leehaven Road—very close to the name used by Thomas Robins Hollyday for his farm that was located in that area.[77] The town of Easton has a Glenwood Avenue located east of the river and the former Glenwood farm.[77]

The town of Easton began public hearings in 1999 concerning the annexation and zoning of more than 386 acres (156 ha) of Ratcliffe Manor land and Glenwood farm. Residents were concerned with the proposed development of the acreage and its impact on the environment.[78] The area was annexed by the town of Easton in 1999 and 2000, and two projects were planned.[2] In 2004, Maryland's Critical Areas Commission approved a plan for a Ratcliffe Manor Farm subdivision.[79] This project had a buffer management plan and a habitat management plan approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The development is along portions of the Ratcliffe Manor estate waterfront, located on the peninsula formed by the Tred Avon River and Dixon Creek. It consists of 15 single-family lots.[79]

The land northeast of Radcliffe Manor Farm became the development project named Easton Village, and it partially overlaps with the Glenwood farm. This project was rejected by town planners in 2002. After changes to the original proposal, the state's Critical Areas Commission approved a plan in 2004 that included a buffer management plan and a habitat management plan. Work began on the 250-home project in 2005, with new homes planned to be available in 2006.[79] Easton Village is separated from Ratcliffe Manor Road, and Ratcliffe Manor Farm, by wooded areas.[80] Most of these wooded areas are 300-foot (91 m) buffer areas designed to preserve forests and provide habitats for wildlife.[79] Sources do not agree on the exact location, but somewhere beneath either Easton Village or Ratcliffe Manor Farm lies the remnants of the old airstrip constructed by the Hathaway brothers in the 1920s.[81][68]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The Ratcliffe Manor property was annexed by the Town of Easton in 1999, and Ratcliffe Manor Lane was annexed in 2000.[2]

- ^ At least two sources, a book published in 1907 and a 1928 newspaper article, claim that Ratcliffe Manor was constructed with bricks from England.[9][10]

- ^ The Maryland Historical Trust file T-42, Ratcliffe Manor (Radcliffe Manor), is currently (March 2023) a 103-page PDF last updated (first page of PDF) on March 21, 2013, and the original portion of the survey form for the manor house was written in 1976 (see second page of PDF).[1] Other portions of the file are dated December 8, 2003 (ninth page of PDF); April 2, 1992 (72nd page of PDF); August 1976 (81st page of PDF); and August 30, 1967 (83rd page of PDF).[1]

- ^ In the 21st century, boxwoods in Maryland have been victims of Boxwood blight.[15]

- ^ Examples of Ratcliffe Manor being part of the Maryland House and Garden Pilgrimage tour are May 1960 and May 1962.[19][20] Other events, such as a fundraiser for the Pickering Creek Audubon Center and the Historical Society of Talbot County, have also taken place (2008) on the grounds of Ratcliffe Manor.[21]

- ^ Multiple sources use "1659/60" as the year of the patent.[25][26][27] The reason for the unusual year of "1659/60" is that England was still using the Julian Calendar instead of the Gregorian Calendar, and its new year did not start until March 25 (instead of January 1). The Ratcliffe Manor patent says "1659" for its date, but if the Gregorian Calendar was being used it would have said 1660. In late 1752, England adopted the Gregorian calendar, which aligned it with the rest of Europe.[28]

- ^ Captain Robert Morris is apparently not related to Robert Morris of Liverpool, who lived in nearby Oxford, Maryland, in the first half of the 18th century—and Robert Morris of Liverpool is the father of the Robert Morris that is considered a founding father of the United States.[29][26][27]

- ^ Sources do not agree on Wasse's first name. At least two newspaper articles (1989 and 1962) identify Wasse as "James Wasse".[26][30] Bordley (1962) says that "James Wass" sold the property...."[31] An older source (1938) says that Morris sold the property to "Henry Wasse".[25]

- ^ Sources do not agree on Bartlett's name or the date of purchase. One source says the property was sold to Bartlett in 1698.[30] Bordley (1962) says Wass sold the property to "Samuel Bartlett, who in 1713 sold 329 acres (133 ha) to Robert Hopkins and later left the remainder to his three sons, Thomas, John and Samuel."[31] An older source (1938) says that the property became owned by "Thomas Bartlett" prior to 1705, and the property was divided in a 1711 will among the Bartlett children: Thomas, John, James, and Mary.[25] Another source says Thomas Bartlett came to Talbot County in 1692, and settled on Ratcliffe Manor. He died in 1711, and his children were Thomas, John, James, Mary and Esther.[32]

- ^ Wye Plantation, home of Frederick Douglass for a short period while he was a slave, initially consisted of 3,500 acres.[33] It was owned by the Lloyd family—including Edward Lloyd II, who was a former governor of the Province of Maryland.[34] Sarah Covington Lloyd was the widow of Edward Lloyd II, and mother of Edward Lloyd III, when she married James Hollyday.[12] Until Lloyd III came of age, James Hollyday ran the plantation. At the end of Edward Lloyd III's life, he owned 252 slaves and over 40,000 acres of land.[12]

- ^ Author Oswald Tilghman claims that Sara Hollyday corresponded with Charles Calvert for insight on Readbourne's architecture.[36] A more recent source, James Bordley, wrote that there is no evidence of any correspondence between Hollyday and Lord Baltimore, and although it is possible that "at some function given Lord Baltimore he may have made some suggestions to Mrs. Hollyday but it seems improbable. There is no record of his visiting the Eastern Shore on his trip to Maryland."[37]

- ^ Maryland Historical Magazine says the marriage happened on December 9, 1748—but has a footnote that says in St. Peters Parish records for Talbot County, the "date of the wedding is Dec. 9, 1749."[7] The church record is incorrect, as a letter and a will, both written in mid-1749, discuss the marriage as already completed.[40]

- ^ Thomas Hollyday had an "evil temper" and a "progressive mental disturbance".[44] He died in 1823.[44]

- ^ William Green, who did not live at Ratcliffe Manor, was a slave from the Oxford area of Maryland's Eastern Shore.[48] He escaped in 1840, and in 1853 wrote a book about his experiences.[49] In his book, he devoted a few pages describing a man named "Harry Holliday" who mistreated slaves.[50]

- ^ Tredhaven Creek, also known as Third Haven River, is now called Tred Avon River.[55]

- ^ The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) documents "achievements in architecture, engineering, and landscape design in the United States and its territories", and is administered through cooperative agreements between the private sector, Library of Congress, and National Park Service.[72] HABS photographs of Ratcliffe Manor are dated 1936 and 1940.[71]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "T-42 Ratcliffe Manor (Radcliffe Manor)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Land Use (see 5th page of PDF)". Easton, Maryland. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c Bordley 1962, p. 118

- ^ a b Bordley 1962, p. 119

- ^ "Maryland's History". Maryland.gov – Kids Pages. Archived from the original on April 30, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, p. 4

- ^ a b c d e Bordley, Jr, James (March 1950). "Ratcliffe Manor" (PDF). Maryland Historical Magazine. XLV (1). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society: 73–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2023.; Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 47

- ^ Coffin & Holden 1919, p. 13

- ^ Shannahan 1907, p. 61

- ^ "Beautiful Ratcliffe is about Two Centuries Old". Easton Star-Democrat. February 18, 1928. p. 10.

Ratcliffe is an exception, for the receipts show that the bricks were brought to this country from England.

- ^ a b c Clemens, Paul G. E. (July 1975). "The Operation of an Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Tobacco Plantation". Agricultural History. 49 (3). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press: 517–531 JSTOR. JSTOR 3741788. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c Speckart, Amy (2011). "The Colonial History of Wye Plantation, the Lloyd Family, and their Slaves on Maryland's Eastern Shore: Family, Property, and Power". Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623580. Williamsburg, Virginia: William and Mary University. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Bordley 1962, p. 120

- ^ "Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey – Ratcliffe Manor, 7768 Ratcliffe Manor Road, Easton, Talbot County, MD". U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ "Boxwood Blight, A newly emerging disease" (PDF). Maryland Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Hammond 1914, pp. 148–149

- ^ Hammond 1914, p. 148

- ^ "Ratcliffe Manor Feature of Forthcoming Garden Tour". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland). April 12, 1957. p. 3 of Section Two.

- ^ Breem, Robert G. (May 3, 1960). "Manorial Living Did Have Its Points". Baltimore Sun.

Such is Ratcliffe Manor, surrounded on three sides by the undulating Tred Avon River, and embraced by the encircling arms of magnificent elms, a massive hawthorne, flowering chesnuts, beech and arborvitae.

- ^ "Manor House Faces Tred Avon". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland). April 6, 1962.

Among the homes on the tour will be Ratcliffe Manor.

- ^ "Tour, Toast & Taste set for June 14 at Ratcliffe Manor". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland). June 6, 2008.

...a joint fundraiser on the grounds at historic Ratcliffe Manor near Easton.

- ^ Weeks, Bourne & Maryland Historical Trust 1984, p. 33

- ^ Carson & Lounsbury 2013, p. 141

- ^ a b "The National Archives – Manorial Definitions". The National Archives (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Owings, Donnell MacClure (December 1938). "Private Manors: An Edited List" (PDF). Maryland Historical Magazine. XXXIII (4). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society: 307–334 (see pages 308 and 326). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Preston, Dickson J. (January 1989). "Talbot Yesterday – The Robert Morris Nobody Knows About". Tidewater Times. pp. 93–98.

"...he was in all probability no relation whatever to the better-known Robert Morris....

- ^ a b c Scisco, Louis Dow (December 1943). "Captain Robert Morris of Ratcliffe Manor". Maryland Historical Magazine. XXXVIII (4). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society: 331–336.

- ^ "The Julian Calendar/The Gregorian Calendar" (PDF). Maryland State Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 19, 2023. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ "The Oxford Museum – Robert Morris". The Oxford Museum. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Manor House Faces Tred Avon". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland). April 6, 1962. p. 2 of Section Three.

In 1667 it was sold to James Wasse....

- ^ a b Bordley 1962, pp. 117–118

- ^ Hall 1912, pp. 599–600

- ^ "History of Early American Landscape Design - Wye House". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Wye House". Maryland Historical Trust. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ Hollyday, George T. (1883). "Biographical Memoir of James Hollyday". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 7 (4). University of Pennsylvania Press: 426–447 JSTOR. JSTOR 20084625. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 47

- ^ Bordley 1962, p. 70

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 47–48

- ^ a b "QA-9 Readbourne" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Bordley 1962, p. 124

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 64

- ^ a b c Bordley 1962, p. 66

- ^ Hammond 1914, p. 150

- ^ a b Bordley 1962, p. 125

- ^ Looney & Woodward 1991, p. 64

- ^ a b c Looney & Woodward 1991, p. 65

- ^ a b Bordley 1962, p. 168

- ^ Green 1853, p. 3

- ^ Green 1853, p. Bibliographical note

- ^ Green 1853, pp. 7–8

- ^ a b Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, p. 152

- ^ a b "Easton Point". Choptank River Heritage. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Griffith, Jean (March 28, 2012). "Fort Stokes and the Defense of Easton". Star Democrat (Easton, Maryland). Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, p. 151

- ^ "Tred Avon River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, pp. 151–152

- ^ Sheads & Turner 2014, pp. 44–49

- ^ "Old Fort Stokes May Be Restored". The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware) (Newspapers.com by Ancestry). November 30, 1946. p. 11.

Easton May Rescue Vestige of War of 1812 From Neglect

- ^ "Star-Spangled Banner National Historic Trail – Maps". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c Bordley 1962, p. 170

- ^ Bordley 1962, p. 169

- ^ Bordley 1962, pp. 170–171

- ^ "The News of the Week (page 4 second column from left)". Saint Mary's Beacon (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 2, 1889. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Gibson 1894, p. 38

- ^ "History, Art & Archives – United States House of Representatives – Gibson, Charles Hopper". United States House of Representatives, Office of Art & Archives, Office of the Clerk. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ a b "Ratcliffe Manor at Auction (page 2 center)". Washington Evening Times (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). October 17, 1899. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ a b "Hollyday v. Southern Farm Agency, 100 Md. 294 (1905)". Harvard Law School Caselaw Access Project. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ a b "Easton Airport Celebrates 75th Anniversary". Maryland Airport Managers Association. May 22, 2018. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ Preston 1983, p. 300

- ^ "The Estate is One of the Finest on the Eastern Shore – Consists of Over Three Hundred Acres". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland). May 22, 1936.

Ratcliffe Manor, one of the oldest and best known estates on the Eastern Shore of Maryland was sold on Wednesday....

- ^ a b "Ratcliffe Manor, 7768 Ratcliffe Manor Road, Easton, Talbot County, MD". United States Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ "Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Swann 1975, p. 168

- ^ Smith, Owen & Smith 1989, pp. 2–3

- ^ a b c Smith 2012, p. 51

- ^ Barnes, Bart (July 6, 1994). "Gerrard Smith, arms Control Negotiator, Dies". Washington Post. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c 38°45'44.4"N 76°06'40.0"W (Map). Mountain View, California: Google Maps. 2023. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Tobias, Tara; Griep, John (January 4, 1999). "Hearings to tackle annexation". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland).

A residential development and a golf course are being considered as elements of a land plan....

- ^ a b c d Fisher, Vicki (August 19, 2005). "Work Begins on Easton Village Project". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland).

Elm Street Development's Easton Village project is in its beginning stages along State Route 33 and Easton Parkway.

- ^ 38°45'44.4"N 76°06'40.0"W (Map). Mountain View, California: Google Maps. 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- ^ Cooper, Dick (October 2015). "Talbot County Historical Society Builds New Museum in Old Space". Tidewater Times (page 30). Tidewater Times Inc. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

References

[edit]- Bordley, James (1962). The Hollyday and Related Families of the Eastern shore of Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society. OCLC 1144650132. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- Carson, Cary; Lounsbury, Carl R. (2013). The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80783-811-2. OCLC 830169767.

- Coffin, Lewis A.; Holden, Arthur C. (1919). Brick Architecture of the Colonial Period in Maryland and Virginia. New York City: Architectural Book Publishing. OCLC 1031627842. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- Gibson, Marietta Fauntleroy Hollyday (1894). Mrs. Charles H. Gibson's Maryland and Virginia Cook Book. Baltimore, Maryland: J. Murphy. OCLC 1049689114. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- Green, William (1853). Narrative of Events in the Life of William Green (Formerly a Slave). Springfield, Massachusetts: L. M. Guernsey. OCLC 367555950. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Hall, Clayton Colman, ed. (1912). Baltimore: Its History and Its People. New York City: Lewis Historical Publishing Co. OCLC 1178422. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- Hammond, John Martin (1914). Colonial Mansions of Maryland and Delaware. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J.B. Lippincott Company. OCLC 478945. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- Looney, J. Jefferson; Woodward, Ruth L. (1991). Princetonians. 1791-1794: A Biographical Dictionary. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-40086-127-9. OCLC 920465909.

- Preston, Dickson J. (1983). Talbot County: A History. Talbot County, Maryland: Tidewater Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87033-305-7. OCLC 1301366619.

- Shannahan, John Henry Kelley (1907). Tales of Old Maryland: History and Romance on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland: Press of Meyer and Thalheimer. OCLC 7580272. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- Sheads, Scott S.; Turner, Graham (2014). The Chesapeake Campaigns 1813–15: Middle Ground of the War of 1812. Oxford, Oxfordshire, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-852-0. OCLC 875624797.

- Smith, Gerard C.; Owen, Henry; Smith, John Thomas (1989). Gerard C. Smith: a Career in Progress. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-81917-444-4. OCLC 28343262.

- Smith, John Thomas (2012). Cars, Energy, Nuclear Diplomacy and the Law : a Reflective Memoir of Three Generations. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-44222-012-6. OCLC 1253438378.

- Swann, Don (1975). Colonial and Historic Homes of Maryland - 100 Etchings by Don Swann. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. OCLC 723887173.

- Tilghman, Oswald; Harrison, Samuel Alexander (1915). History of Talbot County, Maryland, 1661-1861 - Volume I. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins Company. OCLC 1541072. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- Tilghman, Oswald; Harrison, Samuel Alexander (1915a). History of Talbot County, Maryland, 1661–1861 – Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins Company. OCLC 1541072. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- Weeks, Christopher; Bourne, Michael O. Bourne; Maryland Historical Trust (1984). Where Land and Water Intertwine: An Architectural History of Talbot County, Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80183-165-2. OCLC 10696846.

External links

[edit]- Ratcliffe Manor - Society of Architectural Historians

- Garden Plan of Ratcliffe Manor – Smithsonian Gardens

- Anna Maria Robins Hollyday – Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch