Robert James Harlan

Robert James Harlan | |

|---|---|

Sketch from The Cincinnati Enquirer, September 22, 1897 | |

| Member of the Ohio House of Representatives from Hamilton County | |

| In office March 26, 1886 – 1887 | |

| Preceded by | Multi-member district |

| Succeeded by | Multi-member district |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 12, 1816 Mecklenburg County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | September 21, 1897 (aged 80) Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Josephine Floyd |

| Occupation | horse racer, gambler, entrepreneur, civil rights activist, civil servant, and politician |

| Signature | |

Robert James Harlan (December 12, 1816 – September 21, 1897) was a civil rights activist and politician in Cincinnati, Ohio in the 1870s-1890s. He was born a slave but was allowed free movement and employment on the plantation of Kentucky politician James Harlan, who raised him and may have been his father or half-brother. He became interested in horse racing as a young man and moved to California during the 1849 Gold Rush where he was very successful. In 1859 he moved to England to import racehorses from America and race them in England. He returned to the United States in 1869 during reconstruction. He became friends with Ulysses S. Grant and became involved in Republican politics. For the rest of his life, he was involved in city, state, and national African-American civil rights and political movements. In 1870 he became colonel of the Second Ohio Militia Battalion, a black state militia battalion in Cincinnati. In 1886, he became a member of the Ohio House of Representatives.

Early life

[edit]Birth and move to Kentucky

[edit]Robert James Harlan was born on December 12, 1816, probably in Mecklenburg County, Virginia. His father was the slave owner of his mother,[1] Mary Harlan,[2] and himself. His mother was also of mixed-race, and Robert was not easily identifiable as black. Early in his life, perhaps at the age of eight,[1] or three[3] Robert and his mother were sent to Cincinnati. The trip was made on foot, before the advent of railroad connections, and when they reached Danville, Kentucky, they received word that Robert's father had died and they were seized as parts of his property to be sold. Robert was purchased by James Harlan of Danville and his mother was sold South.[4] James Harlan worked in dry goods, and became a lawyer and politician, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky from 1835 to 1839. His son, John Marshall Harlan, born in 1833, served as a US Supreme Court Justice from 1877 to 1911 and was known as the "Great Dissenter" for his support of civil rights against the segregationist majority court. The role of Robert Harlan in John Marshall's ideas is discussed in detail in Gordon (2000).[5] It was then that Robert took the name Harlan.[3]

Birthplace and paternity

[edit]

It is suggested that Robert's father was his Kentucky master, James Harlan, contradicting the story that his father died during Robert's trip with his mother to Cincinnati. Gordon (2000)[5] traces this theory to a short biography of Robert in Dictionary of American Negro Biography by Paul McStallworth published in 1983,[6] which is based on a biography of Robert in the Cincinnati Union on December 13, 1934, 37 years after Robert's death and places Robert's birth in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, then home of James Harlan. Newspaper articles during[4] and immediately after[3] Harlan's life as well as biography written about him during his life[1] state that Robert was born in Virginia and James Harlan did not become Robert's master until later. However, Loren Beth proposes in a biography of John Marshall Harlan that if Robert was born in Virginia, it may have been John Marshall Harlan's grandfather, also named James, who fathered Robert.[2]

Education and training

[edit]When Robert reached schooling age, James sent him to the village school at Harrodsburg along with his own sons.[3] Robert was special in this regard; while his master was ambivalent about slavery, he did not routinely educate his slaves.[5] A black janitor notified the school that Robert was black,[4] and Robert was discharged from the school, an occurrence which led Robert to joke later in life that he had only "a half a day's schooling." Robert was close to James' older sons, Richard and James, and when the children came home from school, Robert would study the same lessons as the other children, and thus became educated.[3] Robert made money hunting and selling coonskins, and moved to Louisville where he learned to be a barber.[4] At 16, Robert opened a store at Harrodsburg, where the Harlans had moved in the early 1820s. At 19 he had saved enough money to buy a race horse. From this point, Harlan began racing and gambling on horses throughout the South and Southwest with good success.[3]

Although not formally freed, by 1840, Robert moved to Lexington, Kentucky where he appears in records as a "free man of color". That year James Harlan moved to Frankfort, Kentucky to become Kentucky's Secretary of State.[5]

Later, he married a woman from Lexington and he sold his shop in Harrodsburg and opened a grocery in Lexington. About the time Reverend John Tibbs was tarred and feathered and run out of Kentucky for his work educating black children, and Harlan decided Lexington was not a safe place to live and he moved to Louisville.[4] In the 1840s, Harlan and his wife had five daughters.[5]

California Gold Rush and move to Cincinnati

[edit]Robert's de facto emancipation was illegal and may have become a political liability for his master by the late 1840s. On September 18, 1848, James Harlan went to the Franklin County, Kentucky, Courthouse to formally free Robert. James continued to hold slaves after that date, with fourteen slaves appearing in his household in the 1850 census. James would die in 1863, but Robert continued to be in contact with James' sons; James Harlan Jr. looked to Robert for financial assistance in the 1880s.[5]

In 1848[4] or 1849, Harlan moved to California to seek his fortune. He opened a trading store with $2,000 he had made selling his horses. He was very successful in California, amassing about $50,000.[3] He then moved to Cincinnati, achieving the goal he and his mother had for themselves many years before. At some point before moving to England, he paid a visit to James Harlan's family in Harrodsburg. James' wife showed Robert a letter James had from Robert's mother which had been written fourteen years earlier at Point Confee, Louisiana. Robert traveled to that place and learned that his mother had been sold back on the Attakapas. He met his mother there and purchased her freedom. However, she was married to the plantation foreman and preferred to stay with her husband rather than return North.[4]

Harlan began working as a benefactor for black people in Cincinnati, becoming a trustee of the colored schools there and negotiating with Nicholas Longworth, Esq. for the building of the Eastern District School.[4] He speculated in Cincinnati real estate and earned enough[3] to purchase Bull's First Class Photographic and Daguerreotype Gallery[1] where he employed a number of well known photographers including Charles Waldeck, James Landy, and Leon Van Loo.[3] In 1851, he visited the World's Fair in London. About this time,[1] he was or considered himself technically owned by James Harlan, although he was wealthier than the slave owner and had been freed a few years earlier. Robert returned to Kentucky and paid James $500 for his freedom.[4] In Cincinnati, his fortune continued to grow, but in 1859 Harlan desired to escape the discrimination he felt in America and move to England to race horses.[3]

Horse racing in England

[edit]Harlan moved to England with jockies Charley Kyte and Johnnie Ford, who later became a prominent horse trainer. Harlan's trainer was John Minor, whose son had a prominent career in the Lorillard stables. Harlan's thoroughbred race horses in England included the Cincinnati, Ochiltree, Deschiles, Powhattan,[3] and Lincoln.[7] He also brought a Kentucky trotting horse named Jack Rossiter. He stayed in England for ten years, adding more horses to his stable during that time. He was close friends with and adviser to another famous American turfman in England, Richard Ten Broeck.[8] Ten Broeck was the first American to ship a stable of horses to England, and Harlan was the second. Harlan made a number of famous, successful, large wagers in England. Harlan won a $5,000 wager that Jack Rossitter could trot 18, 19, and then 20 miles in an hour, a great feat for a trotting horse in England at that time. Harlan won $40,000 betting on Ten Broeck's horse, Prioress, when she won the Czarowitz stakes at 200 and 100 to 1.[3] When he left America, Harlan invested his money into American securities which at the time would earn him an income of $7,000 per year. However, his investment lost most of their value during the American Civil War which spanned 1861–1865. In 1869, Harlan returned to Cincinnati,[3]

Ohio politics

[edit]Second Ohio Militia Battalion

[edit]Harlan quickly became an important figure in Cincinnati. In 1870, for the first time, blacks were elected as delegates to the Cincinnati City Republican Convention, and Harlan was among them.[9] Also in 1870, black residents of Cincinnati raised an Ohio militia battalion led by William Travis, Wilson Scott, and Harlan.[10] Harlan feuded with Travis over colonelcy of the battalion, which became known as the Second Battalion Ohio Militia, and gained control of the regiment and the title Colonel in October.[11] The split was not total, as Harlan frequently worked with Travis; for instance Harlan was on the Finance Committee of the Grant Club in 1872, a branch Travis organized to support Grant's presidential campaign.[12]

During the 1872 presidential campaign, pro-Grant demonstrators took part in street fights in October against pro-Horace Greeley demonstrators. Weapons from the battalion armory were brought out, but Harlan and other leaders of the battalion were among those who quelled the violence.[13] The Ohio Adjutant-General found that no officers or men from the battalion took part in breaking into the armory or using the guns unlawfully, and the battalion was not punished.[14] Harlan served as colonel for four or five years, and he continued to be referred to with the title Colonel for the rest of his life. Later in life this caused some difficulty, as his military service was not during the Civil War or another war, and it was implied that he had purposely traveled to England to avoid the war and he did not deserve the title.[15] The battalion was disbanded in December 1874 and Harlan was held responsible for guns missing from the armory since the 1872 violence.[16]

Republican Party

[edit]

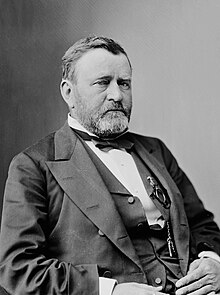

Sharing a love for horses and a common friend in Ohio congressman John Sherman, he became friends with General and later President Ulysses S. Grant.[3] In 1872, Harlan gave a speech in Saratoga Springs, New York, in support of Grant against former Republican-turned-Democrat Horace Greeley, who he felt betrayed blacks in switching allegiances. The speech included a joke about a parrot which became a regular part of Harlan's speeches.[17] At the State Colored Convention on August 22, 1872, Harlan and another black leader, Peter Clark, were strongly divided over whether black Ohioans should support Republican efforts for civil rights, or if Republican leadership was taking advantage of black support, and Harlan spoke strongly in favor of Republicans.[18] Harlan's support was rewarded, and he was elected a delegate to the 1872 Republican National Convention.[19] In December, Harlan was a prominent delegate at the National Colored Convention in Washington, D.C. led by P. B. S. Pinchback, William Nesbit, and Robert B. Elliott. Harlan led a delegation from the convention to call on President Grant, and met with Grant privately for about 15 minutes.[20] In 1873, Grant appointed Harlan mail agent at large,[21] and Harlan made great efforts to support Grant and the Republican Party. In 1874, Harlan was briefly removed as special agent of the Postal Service on the behest of senator John Quincy Smith, but soon was reinstated and given an apology by Smith.[22] Harlan supported Republican efforts for civil rights, and in 1875 asked Benjamin Butler to clarify the scope of the Civil Rights Act, which Butler had authored and which John Marshall Harlan would, in 1883, be the lone Supreme Court Justice to support in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883). Butler's clarification, in the form of an open letter to Harlan, became a national story.[23]

Harlan frequently was a prominent member of other Colored National Conventions, including in April 1876 led by M. W. Gibbs and held in Nashville, Tennessee,[24] in May 1879 led by John R. Lynch again in Nashville.[25] in 1890 (called the Colored Congress and a founding meeting of the National Afro-American League) in Chicago led by T. Thomas Fortune,[26] and in 1892 led by D. A. Rudd in Cincinnati.[27] In 1884 and 1888, Harlan was elected an alternate delegate to the Republican National Convention for the Ohio delegation[19] led by his friend and the future president, William McKinley.[3] He was denied a spot in the 1880 convention, although recommended for the position by a group of black Ohio Republicans.[28]

Ohio House of Representatives

[edit]In 1881, Harlan ran for a seat in the Ohio State House of Representatives and was the only Republican to lose in Hamilton County, out of ten who ran. He was defeated by General Arthur F. Devereux by about 400 votes, and stated that while blacks in Cincinnati voted for the white Republicans in the race, giving them the victory, white Republicans did not vote for him, leading to the loss.[29] In 1885, he ran for the same body and again was the only Republican in the county to lose, with nine others gaining a seat. Democrat A. P. Butterfield was the highest vote getting Democrat. In the House, however, a committee ousted Butterfield and gave Harlan the seat on March 26, 1886.[30]

As a legislator, Harlan was noted for opposing segregated schooling.[31] William Copeland defeated Harlan in the Republican primaries in 1887.[32] Out of elected office in September 1889, Harlan spoke out against the lynchings that were affecting blacks in the South.[33] Later that year, Harlan was appointed an inspector of Customs,[34] and was special inspector of the US Treasury Department until June 1893 when he was retired by President Grover Cleveland.[35]

Death and legacy

[edit]Harlan married multiple times and had at least six children, five daughters and a son. His son, Robert James Jr, was born to Josephine Floyd, reputed to be the daughter of Virginia governor John B. Floyd, in 1853, a year after Robert and Josephine had married. Josephine died when their son was six months old.[36] His daughters were from an earlier wife. A third wife, daughter of Philadelphia caterer Thomas J. Dorsey,[37] died in 1885.[38] He frequently contributed articles to newspapers and occasionally wrote poetry.[39] Robert James Harlan died at age 81 on September 21, 1897. He was a member of the Episcopal Church. His son also reached prominence and held the title Colonel.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e William J. Simmons, Henry McNeal Turner, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising, G. M. Rewell & Company, 1887, p 613-616

- ^ a b Beth, Loren P. John Marshall Harlan: The Last Whig Justice, University Press of Kentucky, February 5, 2015 page 12

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Eventful Life of Robert Harlan", The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), September 22, 1897, page 6. accessed August 5, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/6123842/eventful_life_of_robert_harlan_the/

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Col. Robt. Harlan's Birthday", The Indianapolis Leader (Indianapolis, Indiana) Dec, 18, 1880, page 1 accessed August 5, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/6123701/col_robt_harlans_birthday_the/

- ^ a b c d e f Gordon, James W. "Did the First Justice Harlan Have a Black Brother?" in Critical Race Theory: The Cutting Edge, eds. Richard Delgado, Jean Stefancic Temple University Press, 2000 p 118-125

- ^ McStallworth, Paul, "Robert James Harlan" in Dictionary of American Negro Biography, eds Rayford W. Logan & Michael R. Winston, 1983, p 287-288

- ^ "Turf Matters". Nashville Union and American (Nashville, Tennessee), February 20, 1859, page 2

- ^ "The Turf in England". The Louisville Daily Courier (Louisville, Kentucky), October 7, 1858, page 1

- ^ "The Republican Primary Meetings. Complete Returns from the City--Partial Returns from the Country". Cincinnati Daily Gazette (Cincinnati, Ohio). Thursday, September 1, 1870. page 2

- ^ "The Colored Militia". Cincinnati Daily Gazette (Cincinnati, Ohio),Friday, May 6, 1870, page 2

- ^ [No Headline] Cincinnati Commercial Tribune (Cincinnati, Ohio). Thursday, October 20, 1870. Volume: XXXI Issue: 48 Page: 8

- ^ "The Campaign Commencing. Maj. Travis Organizes a Grant Club and Defines His Position." Cincinnati Daily Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio). Wednesday, June 12, 1872. Volume: XXX Issue: 157 Page: 8

- ^ "Riot". Cincinnati Daily Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio) Tuesday, October 8, 1872. Volume: XXX Issue: 272 Page: 1

- ^ "The Colored Battalion Redivivus", The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), November 26, 1872, page 4 accessed August 8, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/6160811/the_colored_battalion_redivivus_the/

- ^ "Colonel Robert Harlan Answers Our Correspondent and States How He Secured the 'Colonel.'" Cleveland Gazette (Cleveland, Ohio). Saturday, May 28, 1887 Page: 2

- ^ "The Colored Battalion". The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), February 19, 1875, page 8

- ^ "Colonel Harlan at Saratoga". The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio) August 6, 1872. page 3 accessed August 8, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/6161360/colonel_harlan_at_saratoga_the/. Parrot story is in 1872 article, referenced again in "Items on the Wing", The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), October 25, 1890, page 16

- ^ "The Colored Men. State Convention at Chillicothe. Complaints of Political Injustice--Equal Civil Rights Demanded". Cincinnati Daily Gazette (Cincinnati, Ohio). Saturday, August 23, 1873. Page: 1

- ^ a b "His Bodyguard". Cleveland Leader (Cleveland, Ohio). Tuesday, June 2, 1896 Page: 4

- ^ "Washington". Cincinnati Daily Gazette (Cincinnati, Ohio) Saturday, December 13, 1873. Page: 1

- ^ From Our Travelling Correspondent Cincinnati, Elevator (San Francisco, California). Saturday, February 1, 1873. Volume: 8 Issue: 43 Page: 2

- ^ [No Headline], Cincinnati Daily Gazette (Cincinnati, Ohio). Tuesday, March 3, 1874 Page: 4

- ^ "Ben Butler Explains the Civil Rights Bill". Watertown Daily Times (Watertown, New York). Saturday, March 20, 1875. Page: 2

- ^ "The Colored Men's Convention. Thursday, April 6, 1876". Cincinnati Daily Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio). "The Colored Men's Convention Date: Thursday, April 6, 1876" Paper: Cincinnati Daily Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio) Volume: XXXIV Issue: 87 Page: 8. Volume: XXXIV Issue: 87 Page: 8

- ^ [Full Page] People's Advocate (Washington (DC), District of Columbia). Saturday, May 17, 1879. Page: 1

- ^ "Black Men Meet". Duluth News-Tribune (Duluth, Minnesota), Thursday, January 16, 1890 Volume: XX Issue: 234 Page: 1

- ^ "A Protest". Cincinnati Post (Cincinnati, Ohio) Tuesday, July 5, 1892, Page 3

- ^ "Ohio At Chicago, Robert Harlan Recommended for a Delegate to the National Convention". Cincinnati Daily Gazette (Cincinnati, Ohio). Tuesday, April 27, 1880 Page: 6

- ^ "Col. Harlan Explains". Cincinnati Daily Gazette (Cincinnati, Ohio). Wednesday, October 26, 1881 Page: 1

- ^ "Harlan Seated In The Legislature". New York Tribune (New York, New York) Saturday, March 27, 1886. Page: 1

- ^ "Some Race Doings. Baltimore Colored Citizens Having Trouble With Their Separate Schools and White Teachers". Cleveland Gazette (Cleveland, Ohio). Saturday, February 5, 1887 Page: 1

- ^ "Col. Harlan Defeated". Cleveland Gazette (Cleveland, Ohio) Saturday, October 1, 1887 Page: 1

- ^ "Denounced". Cincinnati Post (Cincinnati, Ohio). Tuesday, September 17, 1889. Page: 1

- ^ "Race Gleanings". Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana). Saturday, October 19, 1889. Page: 4

- ^ "Doings Of The Race". Cleveland Gazette (Cleveland, Ohio). Saturday, June 10, 1893. Page: 2

- ^ McNally, Deborah, Harlan, Robert James (1816–1897), blackpast.org, accessed August 8, 2016 at http://www.blackpast.org/aah/harlan-col-robert-james-1816-1897

- ^ Gatewood, Willard B. Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880–1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990

- ^ "City News". Cincinnati Post (Cincinnati, Ohio)Thursday, April 9, 1885. Page: 4

- ^ "In Queer Company". The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee) January 23, 1874, page 4, accessed August 8, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/6160853/in_queer_company_the_tennessean/

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch