Pruth River Campaign

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2014) |

| Pruth River Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Northern War and the Russo-Turkish wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Co-belligerent: | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Total: 260,000–320,000 190,000[3]–250,000 Ottomans[4]70,000 Crimean Tatars[5] | 38,000 Russians[6] 30,000 Cossacks[7]5,000 Moldavians[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | 27,285 including 4,800 in battle[9] | ||||||

The Russo-Ottoman War of 1710–1711,[a] also known as the Pruth River Campaign, was a brief military conflict between the Tsardom of Russia and the Ottoman Empire. The main battle took place during 18–22 July 1711 in the basin of the Pruth river near Stănilești after Tsar Peter I entered the Ottoman vassal Principality of Moldavia, following the Ottoman Empire’s declaration of war on Russia. The ill-prepared 38,000 Russians with 5,000 Moldavians, found themselves surrounded by the Ottoman Army under Grand Vizier Baltacı Mehmet Pasha. After three days of fighting and heavy casualties the Tsar and his army were allowed to withdraw after agreeing to abandon the fortress of Azov and its surrounding territory. The Ottoman victory led to the Treaty of the Pruth which was confirmed by the Treaty of Adrianople.[10]

Background

[edit]The Russo-Ottoman War of 1710–1711 broke out as a result of the Great Northern War, which pitted the Swedish Empire of King Charles XII of Sweden against the Tsardom of Russia of Tsar Peter I. Charles invaded Russian-ruled Ukraine in 1708, but suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Poltava in the summer of 1709. He and his retinue fled to the Ottoman fortress of Bender,[11] in the Ottoman vassal principality of Moldavia. Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III declined incessant Russian demands for Charles's eviction, prompting Tsar Peter I to attack the Ottoman Empire, which in its turn declared war on Russia on 20 November 1710.[11] Concurrently with these events, the ruler (Hospodar) Dimitrie Cantemir of Moldavia and Tsar Peter signed the Treaty of Lutsk (13 April 1711), by which Moldavia pledged to support Russia in its war against the Ottomans with troops and by allowing the Russian army to cross its territory and place garrisons in Moldavian fortresses. In the summer of 1711, Peter led his army into Moldavia and united it with Cantemir's forces near the Moldavian capital Iași; they then advanced southwards along the Pruth river. They aimed to cross the Danube, which marked the border between Moldavia and Ottoman territory proper. Meanwhile, the Ottoman government mobilized their own army, which outnumbered the Russo-Moldavian troops significantly (according to one estimate, by a ratio of six to one). Under the command of Ottoman grand vizier Baltacı Mehmet Pasha, it advanced north to confront the Russians in June 1711.[12]

Military actions

[edit]

Peter assigned Field Marshal Boris Sheremetev to prevent the Ottoman army from crossing the Danube. However, harassment by the forces of the Crimean Khanate, a major Ottoman vassal which supplied the Ottoman army with light cavalry, and his failure to find enough food for his troops prevented him from achieving this objective. Consequently, the Ottoman army succeeded in crossing the Danube without opposition.[13]

Siege of Brăila

[edit]As the Russo-Moldavian army moved along the Prut, a portion of the Russian army under General Carl Ewald von Rönne moved towards Brăila, a major port town located on the left bank of the Danube (in Wallachia) but administered directly by the Ottomans as a kaza. The Russian army met with a portion of the Wallachian army commanded by Spatharios (the second-highest military commander after the ruler) Toma Cantacuzino, who disobeyed the orders of the ruler Constantin Brâncoveanu and joined the Russians. The two armies assaulted and conquered Brăila after a two-day siege (13–14 July 1711).[14]

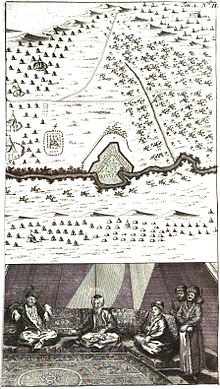

Battle of Stănilești

[edit]Peter and Cantemir concentrated their troops on the right bank of the Prut, across the river from the Ottomans. On 19 July, Ottoman janissaries and Tatar light cavalry crossed the Prut, by swimming or by boat, driving back the Russian advance guard. This allowed the remainder of the Ottoman army to build pontoon bridges and cross the river. Peter tried to bring up the main army to relieve the advance guard, but the Ottomans repulsed his troops. He withdrew the Russo-Moldavian army into a defensive position at Stănilești, where they entrenched. The Ottoman army rapidly surrounded this position, trapping Peter's army. The janissaries repeatedly attacked, but were repulsed, suffering about 8,000 casualties. However, the Ottomans bombarded the Russo-Moldavian camp with artillery, preventing them from reaching the Prut for water.[15] Starving and thirsty, Peter was left with no choice but to sign a peace on Ottoman terms, which he duly did on 22 July. [16][17]

Peace treaty

[edit]The conflict was ended on 21 July 1711 by the Treaty of the Pruth, to the disappointment of Charles XII. The treaty, reconfirmed in 1713 through the Treaty of Adrianople (1713), stipulated the return of Azov to the Ottomans; Taganrog and several Russian fortresses were to be demolished; and the Tsar pledged to stop interfering in the affairs of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The Ottomans also demanded that Charles XII be granted safe passage to Sweden and asked the Tsar to hand over Cantemir. Although Peter acquiesced to all demands, he refused to fulfill the latter, under the pretext that Cantemir had fled his camp.[18]

According to legend the bribe Baltagy Mehmed Pasha received was effective in the fact that the treaty was lighter than the victory (amount of almost 2 wheelbarrows).[19]

Consequences

[edit]

Alexander Mikaberidze argues that Baltacı Mehmet Pasha made an important strategic mistake by signing the treaty with relatively easy terms for the Russians.[20] Since Peter himself was commanding the Russian army, and had Baltacı Mehmet Pasha not accepted Peter's peace proposal and pursued to capture him as a prisoner instead, the course of history could have changed. Without Peter, Russia would have hardly become an imperial power, and the future arch-enemy of the Ottoman State in the Balkans, the Black Sea basin and the Caucasus.

Although the news of the victory was first received well in Constantinople, the dissatisfied pro-war party turned general opinion against Baltacı Mehmet Pasha, who was accused of accepting a bribe from Peter the Great. Baltacı Mehmet Pasha was then relieved from his office.[21]

An immediate consequence of the war was the change in Ottoman policies towards the Christian vassals states of Moldavia and Wallachia. In order to consolidate the control over the two Danubian Principalities, the Ottomans would introduce (in the same year in Moldavia, and in 1716 in Wallachia) direct rule through appointed Christian rulers (the so-called Phanariotes). The ruler Cantemir of Moldavia fled to Russia accompanied by a large retinue, and the Ottomans took charge of the succession to the throne of Moldavia by appointing Nicholas Mavrocordatos as ruler. The ruler Constantin Brâncoveanu of Wallachia was accused by the Sultan of colluding with the enemy. While the Russo-Moldavian army was on the move, Brâncoveanu had gathered Wallachian troops in Urlați, near the Moldavian border, awaiting the entry of the Christian troops to storm into Wallachia and offer his services to Peter, while also readying to join the Ottoman counter-offensive in the event of a change in fortunes. When Toma Cantacuzino switched to the Russian camp, the ruler was forced to decide in favor of the Ottomans or risk becoming an enemy of his Ottoman suzerain, and he swiftly returned the gifts he had received from the Russians. After three years, the Sultan's suspicion and hostility finally prevailed, and Brâncoveanu, his four sons, and his counselor Ianache Văcărescu, were arrested and executed in Constantinople.

Charles XII and his political pro-war ally, the Crimean khan Devlet II Giray, continued their lobbying to have the Sultan declare another war. In the spring of 1712 the pro-war party, which accused the Russians of delaying to meet the terms negotiated in the peace treaty, came close to achieving their goal. War was avoided by diplomatic means, and a second treaty was signed on 17 April 1712. A year after this new settlement, the war party succeeded, this time accusing the Russians of delaying in their retreat from Poland. Ahmed III declared another war on 30 April 1713.[22] However, there were no significant hostilities and another peace treaty was negotiated very soon. Finally the Sultan became annoyed by the pro-war party and decided to help the Swedish king to return to his homeland. Ahmed III also deposed Devlet II Giray from the throne of the Crimean Khanate and sent him into exile to the Ottoman island of Rodos because he didn't show enough respect to Charles XII during the campaigns against Russia (Devlet II Giray considered Charles XII a prisoner and ignored his commands). Charles XII left the Ottoman Empire for Stralsund in Swedish Pomerania, which by then was besieged by troops from Saxony, Denmark, Prussia and Russia.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Formally, the war ended in 1713 after the signing of the Treaty of Adrianople (1713).

References

[edit]- ^ Donald Quataert, The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 41.

- ^ Treaty of Pruth, Alexander Mikaberidze, Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, ed. Alexander Mikaberidze, (ABC-CLIO, 2011), 726.

- ^ A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 712.

- ^ Егоршина 2023, p. 72.

- ^ Егоршина 2023, p. 72-73.

- ^ Stevens C. Russia's Wars of Emergence 1460-1730. Routledge. 2013. p. 267

- ^ Osmanlı-Rus Savaşları A. B. Şirokorad.p;105 (SELENGE YAYINLARI)

- ^ Young 2004, p. 459.

- ^ Егоршина 2023, p. 740.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2011, p. 772.

- ^ a b Walter Moss, A History of Russia: To 1917, (Anthem Press, 2005), 233

- ^ Virginia Aksan, Ottoman Wars, 1700 - 1870: An Empire Besieged, London: Routledge, 2007, 95

- ^ Aksan, Ottoman Wars, 96

- ^ Ionel Cândea, "Asediu Brăilei de la 1711. Două puncte de vedere contemporane Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine", in Analele Universității „Dunărea de Jos" din Galați - Seria Istorie, Seria 19, VII/2008, p. 91-95.

- ^ Aksan, Ottoman Wars, 96 - 97

- ^ Russo-Ottoman War of 1711 (The Pruth Campaign), Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol.1, ed. Alexander Mikaberidze, (ABC-CLIO, 2011), 772.

- ^ Артамонов В. А. Турецко-русская война 1710–1713 гг. — М.: «Кучково поле», 2019. — 448 с.; 8 л. ил.

- ^ Cernovodeanu, Paul (1995), "Notes and comments", in Cantemir, Dimitrie (ed.), Scurtă povestire despre stârpirea familiilor lui Brâncoveanu și a Cantacuzinilor, Bucharest: Minerva Publishing, p. 59

- ^ Я. Е. Водарский Легенды Прутского похода Петра І (1711 г.)

- ^ Russo-Ottoman War of 1711 (The Pruth Campaign), Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol.1, 772.

- ^ Ahmad III, H. Bowen, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. I, ed. H.A.R. Gibb, J.H. Kramers, E. Levi-Provencal and J. Shacht, (E.J.Brill, 1986), 269.

- ^ Stanford J. Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Vol. 1, (Cambridge University Press, 1976), 231.

Sources

[edit]- Mikaberidze, A. (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-336-1.

- Young, W. (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great: A Guide to the Historical Literature. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-32992-2.

- Егоршина, Петрова (2023). История русской армии [The history of the Russian Army] (in Russian). Moscow: Edition of the Russian Imperial Library. ISBN 978-5-699-42397-2.

External links

[edit]- Enciclopedia României - Bătălia de la Stănilești (7/18 – 11/22 iulie 1711) (in Romanian)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch