Sabit Damolla

Sabit Damolla | |

|---|---|

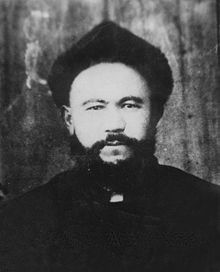

Sabit Damolla in his 20s-30s | |

| Prime Minister of the Turkic Islamic Republic of East Turkestan | |

| In office 12 November 1933 – 6 April 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 1883 Atush, Qing dynasty |

| Died | July, 1934 [1] Aksu, Republic of China[2] |

| Political party | |

Sabit Damolla (Uyghur: سابىت داموللا; Chinese: 沙比提大毛拉·阿不都爾巴克; June 1883 – 1934)[4] was an East Turkestan independence movement leader who led the Hotan rebellion against the Xinjiang Province government of Jin Shuren and later the Uyghur leader Khoja Niyaz. He is widely known as the first and only prime minister of the short-lived Turkic Islamic Republic of East Turkestan from November 12, 1933, until the republic's defeat in May 1934.

Life

[edit]Sabit Damolla Abdulbaqi was born in 1883, in county of Atush (Artux) in the Kashgar vilayet, where he received religious education. In the 1920s, he graduated from Xinjiang Academy of Politics and Laws in Ürümqi (later becoming Xinjiang University), that was founded by Governor Yang Zengxin in 1924 and originally performed courses in Russian, Chinese and Uyghur. After completing university, he visited the Middle East, touring Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Egypt; he also visited the Soviet Union, where he continued his studies. In 1932 he returned to Xinjiang through India, where he joined Emir Muhammad Amin Bughra in preparing a rebellion in Khotan district. Sabit Damulla was convinced that the Islamic world was not interested in supporting Uyghur independence, and so he turned to the Great Powers instead. Yang Zengxin had closed the publishing venture in Artush owned by Sabit Damulla.[5] Sabit was a Jadidist.[6]

Kumul Rebellion

[edit]Between November 12, 1933, and April 6, 1934, he was selected the prime minister of the short-lived Turkic Islamic Republic of East Turkestan (TIRET) in Kashgar. Sabit Damulla was also behind a creation of Independent Government in Khotan on March 16, 1933, which he proclaimed together with Emir Muhammad Amin Bughra. Later this Government expanded its authority to Kashgar and Aksu through the "Eastern Turkestan Independence Association" and contributed to the proclamation of a republic in the Old City of Kashgar on November 12, 1933. Khoja Niyaz, the leader of Kumul Rebellion in 1931, was invited by Sabit Damulla to Kashgar to assume presidency of the self- proclaimed Republic.

Death

[edit]Contemporary sources say that Abdulbaki was captured by Khoja Niyaz near Aksu in late April 1934, then delivered to Governor Sheng Shicai. He was executed reportedly by hanging in July 1934 in Aksu. Previously, in early April 1934, being in his native village of Artush Sabit Damulla rejected several urgent offers from Ma Zhongying to return to Kashgar and form a military alliance against advancing common enemies: Soviet backed Governor Sheng Shicai and Khoja Niyaz. Later sources allege that he was imprisoned by Sheng in Urumchi, where he traded his translation skills for better conditions in his cell. Fellow Chinese Muslims such as Kuomintang officer Liu Bin-Di provided him with the Quran and other Arabic and Chinese Islamic texts to be translated into Uyghur (The establishment of Islam in China in 650 stemmed from the delivery of a Quran by Caliph Usman to Tang Emperor Gaozong in 650 through Envoy Sa'ad ibn Abi Waqqas, one of Muhammad's first companions). Liu had been dispatched from Urumchi to pacify the Hi (Ili) region in 1944, but he was too late.[7] It is unknown if this job was finished, Liu Bin-Di himself was shot dead by rebels in Ghulja in November 1944 during revolt, that led to the establishment of Second East Turkestan Republic on November 12, 1944.

References

[edit]- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 123. ISBN 0-521-25514-7.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 123. ISBN 0-521-25514-7.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 84. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6.

- ^ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Tursun, Nabijan (December 2014). "The influence of intellectuals of the first half of the 20th century on Uyghur politics". Uyghur Initiative Papers (11). Central Asia Program: 2. Archived from the original on 2016-10-12.

- ^ Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs (1982). Journal of the Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs, Volumes 4-5. King Abdulaziz University. p. 299. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Mark Dickens "The Soviets in Sinkiang (1911-1949)". USA 1990.

- Michael Zrazhevsky "Russian Cossacks in Sinkiang". Almanach "Third Rome", Russia, Moscow, 2001

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch