Sei pezzi per pianoforte

| Sei pezzi per pianoforte | |

|---|---|

| Piano music by Ottorino Respighi | |

| English | Six pieces for piano |

| Catalogue | P 044 |

| Composed | 1903–05 |

| Published | 1905–07 |

| Movements | 6 |

The Sei pezzi per pianoforte[note 1] ("Six pieces for piano"), P 044, is a set of six solo piano pieces written by the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi between 1903 and 1905. These predominantly salonesque pieces are eclectic, drawing influence from different musical styles and composers. The pieces have various musical forms and were composed separately and later published together between 1905 and 1907 in a set under the same title for editorial reasons; Respighi had not conceived them as a suite, and therefore did not intend to have uniformity among the pieces. The set, under Bongiovanni, became his first published work. Five of the six pieces are derived from earlier works by Respighi, and only one of them, the "Canone", has an extant manuscript.

The "Valse Caressante" displays elements of French salon; lyricism and Baroque are highlighted in the "Canone"; the most popular of the set, the "Notturno", shows signs of Impressionism; the "Minuetto" is reminiscent of the Classical era; the "Studio" is molded after Chopin's Études; The "Intermezzo-Serenata", resembling Fauré's music, demonstrates Respighi's Romanticism.

Overview

[edit]The set consists of six pieces:[3][note 2]

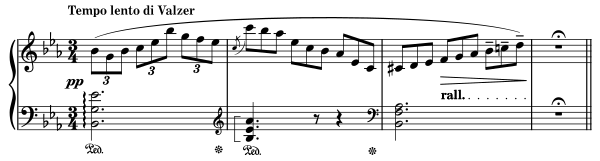

- "Valse Caressante" – E-flat major ("Tempo lento di Valzer.")

- "Canone" – G minor ("Andantino")

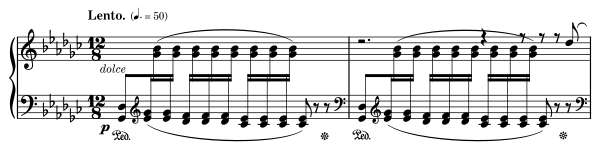

- "Notturno" – G-flat major ("Lento. (

. = 50)")

. = 50)") - "Minuetto" – G major (No tempo marking)

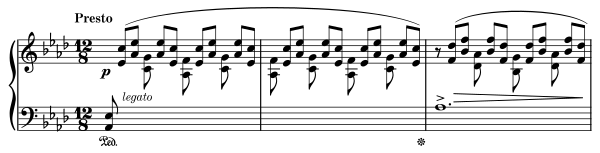

- "Studio" – A-flat major ("Presto")

- "Intermezzo-Serenata" – E major ("Andante calmo")

These predominantly salonesque pieces are eclectic, drawing influence from music of earlier periods, and demonstrate Ottorino Respighi's neoclassical compositional style. A more mature compositional technique brought on from studying abroad with the composers Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Max Bruch is also seen.[5] The set contains various musical forms: waltz, canon, nocturne, minuet, étude and intermezzo.[6] The pieces were composed separately between 1903 and 1905, and then published together between 1905 and 1907 in a set under the same title. Although they were published together, Respighi had not composed them conceiving them as a suite, and therefore did not intend to have uniformity among the pieces; thus, publishing them together was merely an editorial decision. The Sei pezzi per pianoforte, published by Bongiovanni, complete the piano output of his youthful period and was his first published work.[7][8] Five of the six pieces are derived from earlier works by Respighi.[note 3] The manuscripts of the compositions, except for the "Canone", are lost.[10]

Pieces

[edit]"Valse Caressante"

[edit]

The first piece, with the French title "Valse Caressante" ("Caressing waltz"),[12] is a solo piano arrangement of a waltz in E-flat major that Respighi composed for his Six pieces for piano and violin (1901–06). It is dedicated to Cesarina Donini Crema, the wife of the librettist of Respighi's opera Re Enzo.[9][13] The waltz, displaying elements of French salon,[14] is in ABACA rondo form with an introduction and a coda, drawing influence from composers such as Auguste Durand and Frédéric Chopin.[12][15]

The piece begins with an introduction four measures in length,[13] which sets the structure for the rest of the waltz, as every phrase of the waltz is in four measures.[15] In his thesis about Respighi's music, Nathan A. Hess points out the influence Durand's Waltz in E-flat major has on Respighi's waltz: both pieces start with an ornate introduction on the dominant, with Durand employing a ritardando leading to the A section while Respighi uses a fermata following a rallentando, and both pieces mark the first beat of each measure.[16] The A section of the waltz is composed of two motives; the first is an ascending melody in longer note values and the second consists of falling eighth notes. The B section has the melody on the left hand consisting of four measures of ascending and four measures of descending notes; Respighi scholar Potito Pedarra and Respighi researcher Giovanna Gatto hint at its resemblance to a cello. The C section consists of a group of eight notes with accents constantly switching from note to note, which, in a study of Respighi's music, Luca G. Cubisino compares to Chopin's Waltz in F major, Op. 34 No. 3. The A section is repeated a final time and is followed by a coda that ends the work.[9][17][18] Stephen Wright calls the piece "suave and urbane."[19]

"Canone"

[edit]

Originally a part of the unfinished Suite, P 043,[10] the "Canone" ("Canon") in G minor is a canon at the octave, demonstrating a more romantic, serious texture that shows the influence of Johann Sebastian Bach, César Franck and Ferruccio Busoni,[20][21] as well as the Baroque period in general.[14] The entire piece stays at the octave, with the comes (the voice following the leading voice) appearing in the tenor, something Hess compares with Bach's 24th variation of the Goldberg Variations.[22]

The canon is composed of four sections. The first is the Andantino, a canon in two wherein the dux (the leading voice), played at the higher register, is echoed by the comes one octave lower and two beats later. Following a varied repetition of the Andantino, the Agitato appears, switching to the key of E-flat minor. It is characterized by ascending sixteenth notes followed by three descending notes (of longer value), where the comes is on the seventh beat. The section uses two-note grouping reminiscent of the first section, a pattern prevalent in the works of Respighi. The grouped notes eventually transform into technically challenging double sixths that ascend, while the left hand plays a descending scale leading to the grand climax—the Largamente C section. Here, the canon from the opening, now in the major tonic, reappears as triumphant ff octaves with the dux on the left hand. Subsequently, the second half of the A section is repeated and is followed by an expressive coda that ends the piece.[23][24][25][26] The piece was praised for its lyricism,[27] which led Hess to opine that "we sometimes lose track of imitation between the existing voices."[20]

"Notturno"

[edit]

The most popular of the set,[28] the "Notturno" ("Nocturne") in G-flat major, represents one of Respighi's finest piano compositions and is often featured as a stand-alone piece in recitals by distinguished pianists.[29][30][31][note 4] An eclectic work showing signs of Impressionism and Romanticism, this modern piece is signified by tranquil alternating chords (arpeggios) accompanying a "mesmeric melody" with long pedal holds;[33][29] it has been described as "an exercise in musical moonlight and shadow",[34] and as having a "distinctly Rachmaninovian feel".[35] The metronome marking shown on the first page ("Lento. (![]() . = 50)"[36]) was most likely added by the publisher, as Respighi only wrote verbal tempo indications in his early period.[37][30]

. = 50)"[36]) was most likely added by the publisher, as Respighi only wrote verbal tempo indications in his early period.[37][30]

Hess compares the work with Chopin's Nocturne in D-flat major, Op. 27, No. 2, emphasizing the influence of the left hand ostinato which in Respighi's work is an arpeggio split between both hands. The opening unfolds with this pattern in double thirds, similar to the music of Claude Debussy with its chord progression: E-flat minor – G-flat major seventh – C-flat major seventh. At measure seven, an A natural appears in the predominantly pentatonic opening, which resolves to B-flat two measures later, likewise showing resemblance to Chopin.[36][38] The ostinato becomes more note-dense with increased harmonic instability on the second page, passing through the relative minor—E-flat minor. The theme is then played in a gradual crescendo manner, propelling it to the middle section. Dense, accented f chords are played in common time in the middle register, and are immediately answered with the soft ostinato arpeggios in a higher register in compound quadruple meter. Runs of ascending sixty-fourth notes replace the arpeggio ostinatos, preparing for the climax. After a ff half-diminished chord at the climax, an embellished cadenza-like coloratura resembling that of Chopin appears, bringing the piece to the coda that echoes the beginning of the piece.[30][39][40][41] The musicologist Albert Faurot calls the Notturno his "best piece",[33] and the musicologists Maurice Hinson and Wesley Roberts call it Respighi's "finest work for piano."[27] Sergio Martinotti[30] and Elias-Axel Pettersson[42] also spoke fondly of the composition. Jed Distler said that it has "more than a few muffled, overpedalled moments."[43]

The "Notturno" has been arranged for piano and organ,[44] as well as for harp.[45] Stand-alone recordings of the piece by distinguished pianists include those by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli,[46] Sergei Babayan[47] and Imogen Cooper.[48]

"Minuetto"

[edit]

The "Minuetto" ("Minuet") in G major is based on an earlier composition by Respighi, the Minuetto per archi ("Minuet for strings") from 1903. Dedicated to the composer's study companion Adele Righi, it illustrates Respighi's adoration for archaism, showing influence of Baroque and Classical music, but also Maurice Ravel and Debussy. The piece is in rounded binary form with a trio and has no tempo marking. Cubisino associates the work with Ravel's Menuet antique.[11][41][49][50]

The minuet is characterized by thematically contrasting four-measure phrases. The first phrase is a simple doubled melodic line played by both hands an octave apart, as well as a tonic pedal point on G reminiscent of a musette. The third beat of the first and third measures are accented, which Hess suggests creates a "hemiola effect to go along with the minuet's dance steps, which involve a six-beat pattern spanning two measures." The second phrase consists of detached major triads around the dominant. The second section marked Poco più vivace begins with a cascade of sixteenth notes while also using four-measure phrases; Pedarra & Gatto assess that it "looks forward to the Antiche danze per liuto". The trio section marked Un poco più mosso contrasts the minuet with a faster tempo and a shift to C minor. Here, the right hand plays double thirds grouped in two while the left hand plays repeated pedal notes in C, which Pedarra & Gatto compare with the pizzicato of a lute. The last line has an ossia which Cubisino points out is a cadenza modeled after the sixteenth-note runs of the second section, which leads to the piece repeating D.C. al fine.[51][52][53][54]

"Studio"

[edit]

The "Studio" ("Study") in A-flat major is an étude that focuses on interlocking fifths and sixths. Dedicated to the Countess Ida Peracca Cantelli, it is characterized by its "distinctly French character."[52][55] The piece is inspired by Chopin's Études, using the same structure and form as Chopin: changing key signatures, alternating hands, and necessary details to master a technical challenge. Due to its harmonies and pedaling, the study has also been compared to Debussy.[56] Interlocking hands and double-note technique are commonplace throughout the study, which becomes evident as the piece progresses.[57][27] The study is also derived from the unfinished Suite, P 043.[10]

The study opens with fast and p sixths which, according to Pedarra & Gatto, create a "timid melodic line". The melodic line gains texture in bar 21 when a motivic dialogue emerges between treble and bass. After a crescendo that leads to the B-flat major climax, the piece gets darker while the motivic dialogue fizzles out. A coda of continuous hand-crossing begins from the middle register and gradually moves to the higher register, bringing the piece to its Chopinesque ending.[52][56][57][58] Hess states that the "Studio" is the hardest piece of the set to perform.[57] Faurot compares the interlocking chords of the nocturne with the study, opining that the latter is "more brilliantly exploited."[33]

"Intermezzo-Serenata"

[edit]

Respighi's "Fauré-like"[59] last piece, the "Intermezzo-Serenata", is a composition from the unfinished Suite, P 043,[10] which itself is a solo piano transcription of a passage of the third act of his opera Re Enzo. Although he was not entirely satisfied with the opera, Respighi did isolate passages that he liked into stand-alone pieces. The "Intermezzo-Serenata" is one of three transcriptions, all of which omit the first ten bars of the original passage.[60][61][note 5]

The opening marked Andante calmo unfolds with a salon-like accompaniment resembling a lute, consisting of four sixteenth notes followed by an eighth note; this persists throughout the piece. Meanwhile, the right hand plays a simple but intimate melody, showing Respighi "at his most romantic." In the B section, passages of irregular rhythms are introduced, such as octuplets and triplets. Concurrently, radical changes of harmony are highlighted, such as a sudden switch from F-sharp minor to F major when the first passage is repeated. Pedarra & Gatto show the similarities between the B section and the louder f section, highlighting that hints of the B section "are crossed with a chordal motif". A variation of the opening is repeated, leading to a brief coda, ending the work.[62][63][64][65]

Reception and recordings

[edit]The Sei pezzi per pianoforte have attracted some attention, receiving a mixed reception. Alan Becker said that the pieces are "brief, tuneful, and fall in the realm of occasional pieces."[66] Sergio Martinotti opined that the set reveals "the birth of an unmistakable stylistic direction", while Giuseppe Piccioli dismissed the set as "lovely but insignificant compositions".[9] Michael Oliver found the set "mildly attractive morceaux de salon, charming but slight."[67] In a Gramophone review of Bongiovanni (Qualiton) recording 5099, which included the Sei pezzi per pianoforte, Jonathan Bellman concluded:

None of these pieces lies outside a salon aesthetic: pretty, elegant, non-virtuoso music. This is not a crime, but it isn't futurism either. These are sweet and fairly unchallenging listening, sometimes growing frankly trivial, but always attractively played. The transformation of Italian lyricism into a 20th Century aesthetic would wait for Luigi Dallapiccola.[68]

| Recordings of the Sei pezzi per pianoforte | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Pianist | Label | Ref |

| 1997 | Konstantin Scherbakov | Naxos Records | [69] |

| 2000 | Riccardo Sandiford | Bongiovanni | [70] |

| 2016 | Michele D'Ambrosio | Brilliant Classics | [71] |

| 2021 | Giovanna Gatto | Toccata Classics | [72] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Or simply Sei pezzi[1][2]

- ^ Three of the pieces—the "Valse Caressante", "Minuetto", and the "Studio"—have a dedicatee.[4]

- ^ The "Valse Caressante" is derived from his Six pieces for piano and violin (1901–06).[9] The "Canone", "Studio", and the "Intermezzo-Serenata" are all part of the unfinished Suite, P&;043.[10] The "Minuetto" is a transcription of the Minuetto per archi ("Minuet for strings") from 1903.[11]

- ^ Despite its popularity, Alan Becker states that it is a rarely heard nocturne compared to other nocturnes.[32]

- ^ Cubisino surmises that it is not certain whether the "Intermezzo-Serenata" came before or after his opera.[61]

References

[edit]- ^ Barrow 2004, p. 230.

- ^ Webb 2019, p. 219.

- ^ Respighi 2006.

- ^ Pedarra & Gatto 2021, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Hess 2005, pp. 34, 91.

- ^ REPP 2022, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Pedarra & Gatto 2021, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Cubisino 2018, pp. 33, 91.

- ^ a b c d Pedarra & Gatto 2021, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e Cubisino 2018, p. 91.

- ^ a b Pedarra & Gatto 2021, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Hess 2005, p. 35.

- ^ a b Respighi 2006, p. 1.

- ^ a b Hess 2005, p. 91.

- ^ a b Cubisino 2018, p. 92.

- ^ Hess 2005, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Respighi 2006, pp. 1, 2, 4, 5.

- ^ Cubisino 2018, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Wright 2017, p. 170.

- ^ a b Hess 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Cubisino 2018, p. 94.

- ^ Hess 2005, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Respighi 2006, pp. 6–9.

- ^ Hess 2005, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Cubisino 2018, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Pedarra & Gatto 2021, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c Hinson & Roberts 2014, p. 813.

- ^ Pedarra 2016, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Cubisino 2018, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b c d Pedarra & Gatto 2021, p. 11.

- ^ Webb 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Becker 2013, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Faurot 1974, p. 251.

- ^ Jacobi 2012, p. 29.

- ^ March et al. 2007, p. 1077.

- ^ a b Respighi 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Cubisino 2018, p. 96.

- ^ Hess 2005, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Respighi 2006, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Hess 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Cubisino 2018, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Steinberg 2007, p. F3.

- ^ Distler 2011, p. XI.

- ^ The Diapason 1953, p. 29.

- ^ Brodeur 2021, p. E.1.

- ^ Pedarra 2016, p. 6.

- ^ Pro Piano 1998.

- ^ Chandos 2021.

- ^ Respighi 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Hess 2005, p. 41.

- ^ Respighi 2006, pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b c Pedarra & Gatto 2021, p. 12.

- ^ Hess 2005, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Cubisino 2018, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Hess 2005, p. 43.

- ^ a b Cubisino 2018, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Hess 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Respighi 2006, pp. 18–21.

- ^ Young 1998, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Pedarra & Gatto 2021, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Cubisino 2018, p. 101.

- ^ Respighi 2006, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Pedarra & Gatto 2021, p. 13.

- ^ Hess 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Cubisino 2018, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Becker 2017, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Oliver 1998, p. 68.

- ^ Bellman 2000, p. 278.

- ^ Naxos Records 1997.

- ^ Bongiovanni 2000.

- ^ Brilliant Classics 2016.

- ^ Toccata Classics 2021.

Sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Barrow, Lee G. (2004). Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936), an Annotated Bibliography. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5140-5.

- Faurot, Albert (1974). Concert piano repertoire: A Manual of Solo Literature for Artists and Performers. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-0685-6.

- Hinson, Maurice; Roberts, Wesley (2014). Guide to the Pianist's Repertoire (4th ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01022-3.

- March, Ivan; Greenfield, Edward; Layton, Robert; Czajkowski, Paul (2007). March, Ivan; Livesey, Alan (eds.). The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music (2008 ed.). London: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-103336-5.

- Respighi, Ottorino (2006). Ancient Airs and Dances & Other Works for Solo Piano. New York: Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-45292-0.

- Webb, Michael (2019). Ottorino Respighi: His Life and Times. Kibworth Beauchamp: Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78901-895-0.

Articles

[edit]- Becker, Alan (2013). "Nocturnes". American Record Guide. Vol. 76, no. 1. Washington, D.C. p. 197.

- Becker, Alan (2017). "Respighi: Piano Pieces". American Record Guide. Vol. 80, no. 2. Washington, D.C. pp. 143–144.

- Bellman, Jonathan (2000). "20th Century Italian Piano". American Record Guide. Vol. 63, no. 6. Washington, D.C. p. 278.

- Brodeur, Michael Andor (2021). "Beyond Vivaldi, a classical playlist to bring on the spring". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. E. 1.

- Distler, Jed (2011). "Gramophone – Sounds of America". Gramophone. London. p. XI.

- Jacobi, Peter (2012). "Variety is spice of life in local music scene". McClatchy-Tribune Business News. Washington, D.C. p. 29.

- Oliver, Michael E. (1998). "Gramophone – August 1998". Gramophone. London. p. 68.

- REPP (2022). "Respighi: Piano Pieces 2". American Record Guide. Vol. 85, no. 1. Washington, D.C. pp. 82–83.

- Steinberg, David (2007). "Pianist rocks Beethoven at El Rey Theater". Albuquerque Journal. Albuquerque. p. F3.

- "New Music for the Organ". The Diapason. Vol. 44, no. 8. Chicago: Scranton Gillette Communications, Inc. 1953. p. 29.

- Wright, Stephen (2017). "Respighi: Piano Concerto; Sonata; Valse Caressante". American Record Guide. Vol. 80, no. 7. Washington, D.C. p. 170.

- Young, John Bell (1998). "Respighi: Piano Pieces including Ancient Airs and Dances; Sonata in F minor; Preludes on Gregorian Melodies". American Record Guide. Vol. 61, no. 6. Washington, D.C. pp. 202–203.

Online

[edit]- Cubisino, Luca G. (2018). Ottorino Respighi: Published and Unpublished Works for Piano Solo. ProQuest (PhD thesis). University of Miami.

- Hess, Nathan A. (2005). Eclecticism in the piano works of Ottorino Respighi. ProQuest (PhD thesis). University of Cincinnati.

- Pedarra, Potito (2016). Booklet to Brilliant Classics recording 94442 (CD booklet). Translated by Rollins, Helen. Brilliant Classics.

- Pedarra, Potito; Gatto, Giovanna (2021). Booklet to Toccata Classics recording TOCC0605 (PDF) (CD booklet). Translated by Napoli, Alberto. London: Toccata Classics.

Recordings

[edit]- Full set

- D'Ambrosio, Michele (2016). Respighi: Complete Solo Piano Music (Recording). Brilliant Classics – via AllMusic.

- Gatto, Giovanna (2021). Ottorino Respighi: Complete Piano Music, Vol. 2 – Original Piano Works II (Recording). Toccata Classics – via AllMusic.

- Sandiford, Riccardo (2000). 20th Century Italian Piano Music (Recording). Bongiovanni – via AllMusic.

- Scherbakov, Konstantin (1997). Respighi: Piano Music (Recording). Naxos Records – via AllMusic.

- The Notturno

- Babayan, Sergei (1998). Messiaen: From Vignt Regards sur l'Enfant Jésus; Vine: Sonata; Respighi: Notturno & Prelude; Ligeti (Recording). Pro Piano – via AllMusic.

- Cooper, Imogen (2021). Le Temps Perdu…: Fauré, Liszt, Ravel, Respighi (Recording). Chandos – via AllMusic.

External links

[edit]

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch