Starman (song)

| "Starman" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

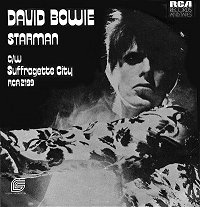

Cover of the 1972 UK single | ||||

| Single by David Bowie | ||||

| from the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars | ||||

| B-side | "Suffragette City" | |||

| Released | 28 April 1972 | |||

| Recorded | 4 February 1972 | |||

| Studio | Trident (London) | |||

| Genre | Glam rock[1] | |||

| Length | 4:16 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Songwriter(s) | David Bowie | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| David Bowie singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Starman" on YouTube | ||||

"Starman" is a song by the English musician David Bowie. It was released on 28 April 1972 by RCA Records as the lead single of his fifth studio album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. Co-produced by Ken Scott, Bowie recorded the song on 4 February 1972 at Trident Studios in London with his backing band known as the Spiders from Mars – comprising guitarist Mick Ronson, bassist Trevor Bolder and drummer Mick Woodmansey. The song was a late addition to the album, written as a direct response to RCA's request for a single; it replaced the Chuck Berry cover "Round and Round" on the album. The lyrics describe Ziggy Stardust bringing a message of hope to Earth's youth through the radio, salvation by an alien "Starman". The chorus is inspired by "Over the Rainbow", sung by Judy Garland, while other influences include T. Rex and the Supremes.

Upon release, "Starman" sold favorably and earned positive reviews. Following Bowie's performance of the song on the BBC television programme Top of the Pops, the song reached number 10 on the UK Singles Chart and helped propel the album to number five. It was his first major hit since "Space Oddity" three years earlier. The performance made Bowie a star and was watched by a large audience, including many future musicians, who were all affected by it; these included Siouxsie Sioux, Bono, Robert Smith, Boy George and Morrissey. Retrospectively, the song is considered by music critics as one of Bowie's finest.

Composition and recording

[edit]"Starman" was written as a direct response to the head of RCA Dennis Katz's request for a single. Author Kevin Cann writes that the title may allude to Robert A. Heinlein's 1953 novel Starman Jones,[2] while Chris O'Leary attributes David Rome's 1965 short story "There's a Starman in Ward 7".[3] The song was recorded on 4 February 1972 at Trident Studios in London,[4] towards the end of the Ziggy Stardust sessions.[5] Also recorded during this session was "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" and "Suffragette City".[4] Co-produced by Ken Scott, Bowie recorded it with his backing band the Spiders from Mars, comprising Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick Woodmansey.[6] Doggett finds it similar to his earlier hit "Space Oddity" in that it is a "space-age novelty hit".[7] The song begins on twelve-string acoustic guitar—a "subdominant" chord followed by "the major 7th of the root" according to author Peter Doggett—that is played across both channels. There are strums of a six-string electric guitar at certain points until the verse begins, then both guitars merge into one channel.[7] The song features a string arrangement from Ronson, which biographer Nicholas Pegg describes as being more similar to the style of Bowie's previous album Hunky Dory (1971) than the rest of Ziggy Stardust.[2]

The chorus is loosely based on "Over the Rainbow" from the film The Wizard of Oz, alluding to the "Starman"'s extraterrestrial origins (over the rainbow) (the octave leap on ("Star-man") is identical to that of Judy Garland's ("some-where") in "Over the Rainbow").[7] Doggett states that whereas "Over the Rainbow" "used its cathartic rise to introduce a refrain that was emotionally, and melodically, expansive", the leap in "Starman" "was followed by a more uncertain melody, reflecting his character's innate lack of confidence."[7] Pegg notes that Bowie would change the chorus to "There's a Starman, over the rainbow" during his performances at the Rainbow Theatre in August 1972, effectively establishing the connection between the two songs.[8] Other influences cited for the track are the T. Rex songs "Hot Love" and "Telegram Sam", showcased on the line "Let all the children boogie" and "la la la" chorus, and the Supremes' "You Keep Me Hangin' On", which contained the same morse code-esque guitar and piano breaks as "Starman".[7][8] The English rock band Suede later "borrowed" the same octave leap for their debut single "The Drowners" and the "la la la" chorus for "The Power" and "Beautiful Ones".[8]

Lyrics

[edit]The lyrics describe Ziggy Stardust bringing a message of hope to Earth's youth through the radio, salvation by an alien 'Starman'. The story is told from the point of view of one of the youths who hears Ziggy. The song has inspired interpretations ranging from an allusion to the Second Coming of Christ,[9] to an accurate prediction of the plot for the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).[10] Similar to fellow album track "Moonage Daydream", Bowie uses American slang, including "boogie", "Hey, that's far out", "Don't tell your papa", and "Some cat was layin' down some rock 'n' roll", which, according to Pegg, "vie with an intensely British sensibility to create a bizarre and beautiful hybrid."[2] Speaking about the lyrics to William S. Burroughs for Rolling Stone magazine in 1973, Bowie said:[11]

"Ziggy is advised in a dream by the infinites to write the coming of a starman, so he writes "Starman", which is the first news of hope that the people have heard. So they latch onto it immediately. The starmen that he is talking about are called the infinites, and they are black-hole jumpers. Ziggy has been talking about this amazing spaceman who will be coming down to save the earth. They arrive somewhere in Greenwich Village. They don’t have a care in the world and are of no possible use to us. They just happened to stumble into our universe by black-hole jumping. Their whole life is traveling from universe to universe. In the stage show, one of them resembles Brando, another one is a black New Yorker. I even have one called Queenie the Infinite Fox."

According to Pegg, this "black-hole jumping" is identical to the BBC television programme Doctor Who serial The Three Doctors, which featured a reunion of the show's lead actors to celebrate its tenth anniversary. The serial was broadcast in early 1973 when Bowie was recording his follow up album Aladdin Sane.[8]

Release

[edit]"Starman" was released as the lead single of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars on 28 April 1972 by RCA Records (as RCA 2199) with "Suffragette City" as the B-side.[12] According to Cann, the single was released in the US on 20 May with a slight variant from the UK single: Bowie's spoken intro was edited out and "to comply with the preferred duration among American radio stations," the song was shortened by ten seconds.[13] The US single was released in both mono and stereo formats.[a][14] The single originally featured a "loud mix" of the "morse-code" piano-and-guitar section between the verse and the chorus. This single mix appeared on the original UK album, but not on other vinyl editions of the album internationally, in which the "morse-code" section was lower in the mix. The single mix appeared on the 1980 compilation album The Best of Bowie, but ChangesTwoBowie (1981) and subsequent compilations featured the more subdued mix, until the "loud mix" finally reappeared on Nothing Has Changed (2014) and on Re:Call 1 as part of the 2015 box set Five Years (1969–1973).[14][15]

"Starman" was sequenced as the fourth track on the album, between "Moonage Daydream" and "It Ain't Easy",[16] released on 16 June 1972.[17] It was a late addition to the album, replacing a cover of American singer-songwriter Chuck Berry's "Round and Round".[4] According to Rob Sheffield, "Round and Round" would have fit the concept of the album but it was excessive, as side two featured multiple Berry-style tracks.[18] Pegg also commented: "It's extraordinary to consider that one of Bowie's definitive songs replaced a Chuck Berry cover almost as an afterthought."[8]

From a commercial point of view, "Starman" was a milestone in Bowie's career: it was his first hit since "Space Oddity" three years before. NME critics Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray reported that "many thought it was his first record since 'Space Oddity'", and assumed that it was a sequel to the earlier single.[19] Pegg states that due to this assumption, the title and acoustic intro might have given the suggestion that Bowie had "only one song in his playbook", but the first lyric changes that. While "Space Oddity" was a pure "science-fiction story", "Starman" is less that and more of a "self-aggrandizing announcement that there's a new star in town."[8]

The single initially sold steadily rather than spectacularly but earned many positive reviews. BBC broadcaster John Peel, in his Disc & Music Echo column wrote: "Now this is magnificent – quite superb. David Bowie is, with Kevin Ayers, the most important, under-acknowledged innovator in contemporary popular music in Britain and if this record is overlooked it will be nothing less than stark tragedy."[20] Chris Welch of Melody Maker predicted: "[Bowie] is taking longer than most to become a superstar, but he should catch up with Rod and Marc soon."[21] On 15 June, Bowie and the Spiders from Mars performed "Starman" on the Granada children's music programme Lift Off with Ayshea, which was presented by Ayshea Brough, whom Bowie had met as a performer in 1969. Joined by Nicky Graham on keyboards, according to Pegg, they performed against a "backdrop of coloured stars"; Woodmansey had at this point not "peroxided" his hair.[2] The performance was broadcast on 21 June in a "post-school" time slot, where it was witnessed by thousands of British children.[22] On 24 June, "Starman" rose to number 49 on the UK Singles Chart and by 1 July, number 41, earning Bowie an invitation to perform on the BBC television programme Top of the Pops.[23][24]

Top of the Pops performance

[edit]

On 5 July 1972, Bowie, the Spiders and Graham recorded a performance of "Starman" for Top of the Pops, which was broadcast on BBC One the next night.[26][27] The group mimed to a pre-recorded backing track, four takes of which were recorded on 29 June, and sang live as per Musicians Union rules.[28] Bowie appeared in a brightly-coloured rainbow jumpsuit, "shocking" red hair and astronaut boots while the Spiders wore blue, pink, scarlet and gold velvet attire.[18][23][26] During the performance, Bowie was relaxed and confident and wrapped his arm around Ronson's shoulder, revealing his white-coloured fingernails and, in Cann's words, "driving home the ambiguous glamour of the Ziggy persona".[23][24] He altered the line "Some cat was laying down some rock 'n' roll" to "Some cat was laying down some get-it-on rock 'n' roll" as a tribute to Bolan.[29][24] Upon singing the line "I had to phone someone so I picked on you ooh ooh", Bowie pointed at the camera, engaging the audience directly, which one fan recalled, "It was as if Bowie actually singled me out...a chosen one...it was almost a religious experience."[30][25] Transmitted the following day,[31] the three minute performance launched Bowie to stardom.[26] According to author David Buckley, "Many fans date their conversion to all things Bowie to this Top of the Pops appearance".[9] It embedded Ziggy Stardust in the nation's consciousness, helping push "Starman" to number 10 and the album, released the previous month, to number five.[32] The "Starman" single remained in the UK charts for 11 weeks. In the United States, the single peaked at number 65 on the Billboard Hot 100 in August 1972.[33]

There's no doubt that Bowie's appearance on Top of the Pops was a pivotal moment in British musical history. Like the Sex Pistols at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester in '76, his performance lit the touchpaper for thousands of kids who up till then had struggled to find a catalyst in their lives.[34]

– BBC radio broadcaster Marc Riley, reflecting on the performance's impact

The performance was watched by a large audience, including many English musicians before they became famous, including Boy George, Adam Ant, Mick Jones of the Clash, Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet,[23] Morrissey and Johnny Marr of the Smiths, Siouxsie Sioux of Siouxsie and the Banshees,[35] John Taylor and Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran,[36] Dave Gahan of Depeche Mode, and Noel Gallagher of Oasis.[18] Many musicians and groups have recalled seeing the performance and reflected on how it affected their lives. The English gothic rock band Bauhaus recalled that seeing Bowie's performance on Top of the Pops was "a significant and profound turning point in their lives". The band thereafter idolised Bowie and subsequently covered "Ziggy Stardust" in 1982.[37] Reflecting on Bowie's impact on music in 2003, Robert Smith of the Cure said: "He was blatantly different, and everyone of my age remembers the time he played 'Starman' on Top of the Pops."[38] Bono of the Irish rock band U2 told Rolling Stone in 2010: "The first time I saw [Bowie] was singing 'Starman' on television. It was like a creature falling from the sky. Americans put a man on the moon. We had our own British guy from space – with an Irish mother."[18] English singer-songwriter Gary Numan, who saw the performance when he was 15 years old, said: "I think it stands as one of the pivotal moments of modern music, or, if not music, certainly a pivotal moment in show business. It must have taken extraordinary courage and/or a monumental amount of self-belief. To say it stood out is an epic understatement. Even as a hardcore T. Rex fan I knew it was special."[29] Ian McCulloch of the English rock band Echo & the Bunnymen said in 2007: "As soon as I heard 'Starman' and saw him on Top of the Pops, I was hooked. I seem to remember me being the first to say it, and then there was a host of other people saying how the Top of the Pops performance changed their lives."[23] Elton John said: "It was so different, it was like Wow. No one had ever seen anything like that before."[39]

The Top of the Pops performance was included on the DVD version of Best of Bowie in 2002. In addition to the TV performances, Bowie played the song for radio listeners on the BBC's Johnny Walker Lunchtime Show on 22 May 1972. This performance was broadcast in early June 1972 and eventually released on Bowie at the Beeb in 2000.[40]

Critical reception

[edit]Ian Fortnam of Classic Rock, when ranking every track on the album, placed "Starman" at number two, behind "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide", writing that there are several things an octave leap can do: one can "guarantee" a hit, one can elicit an emotional response in listeners, but most importantly, when used the right way, can launch a career. While he calls Judy Garland's leap in "Over the Rainbow" the greatest octave leap of all time, Bowie's use of one on both "Starman" and "Life on Mars?" both launched his career.[41] Mojo magazine listed it as Bowie's third best track in 2015, behind "'Heroes'" and "Life on Mars?".[42] In 2018, the writers of NME listed "Starman" as Bowie's 15th greatest song.[43] In a list of Bowie's 50 greatest songs, Alexis Petridis of The Guardian ranked the song 11th, calling it "a series of compelling musical steals" – mentioning the likes of T. Rex, "Over the Rainbow" and "Melting Pot" by Blue Mink – and "a brash announcement of Bowie’s commercial rebirth."[44] In a 2016 list ranking every Bowie single from worst to best, Ultimate Classic Rock placed "Starman" at number 17.[45]

In February 1999, Q magazine listed the single as one of the 100 greatest singles of all time, as voted by readers.[46]

Charts and certifications

[edit] Weekly charts[edit]

| Certifications[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Personnel

[edit]According to biographers Kevin Cann and Chris O'Leary:[66][12]

- David Bowie – lead vocals, acoustic guitar, producer

- Mick Ronson – electric guitar, Mellotron, string arrangement, backing vocals

- Trevor Bolder – bass guitar

- Mick Woodmansey – drums

- Ken Scott – producer

Other releases

[edit]- "Starman" has appeared on numerous Bowie compilations:

- The Best of Bowie (1980) – original UK single mix

- ChangesTwoBowie (1981)

- Fame and Fashion (1984)

- Changesbowie (EMI LP and cassette versions) (1990)

- The Singles Collection (1993)

- The Best of David Bowie 1969/1974 (1997)

- Best of Bowie (2002)

- The Platinum Collection (2006)

- Nothing Has Changed (2014) – original UK single mix

- Bowie Legacy (2016) – original UK single mix

- Bowie's 25 June 2000 live performance of the song at the Glastonbury Festival was released in 2018 on Glastonbury 2000.

In popular culture

[edit]This section contains a list of miscellaneous information. (September 2018) |

Social Media

[edit]The song was a viral trend on TikTok and YouTube Shorts. Cited to be a tribute to Superman, the trend originated in late 2023 to early 2024. It is often linked to Hopemaxxing;[67] a term that refers to the process of maximizing ones hope and outlook on life. Various clips of heroic actions have been overlayed to the song.[68]

TV and film

[edit]- The song appears in the ninth episode of the third season of the series The Crown and plays over the ending credits.[69]

- The song was featured in the 2015 film The Martian and appears on its soundtrack album.[70]

- The song is featured in the first teaser trailer for the 2022 Disney/Pixar animated feature film Lightyear.[71]

- The song appears in the first episode of the miniseries Pistol and is sung by two main characters.[72]

- The song was featured in the 2022 murder mystery film Glass Onion, along with fellow album track "Star".[73]

Commercials

[edit]- In 2016, the song was featured in an Audi Super Bowl commercial.[74]

- The song appears in a 2018 TV commercial for Bleu de Chanel.[75]

Other

[edit]- Writer James Robinson's 1994 comic book series Starman featured a story about an alien named Mikaal Tomas, who went by the alias of Starman while living on Earth. In the opening scene of the tale, Mikaal claims that the people of Earth gave him the name due to the similarities between his own life and Bowie's song.[76]

- 2016 U.S. Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders used the song prominently throughout his campaign.[77]

- The mannequin in Elon Musk's Tesla Roadster which was launched into orbit around the Sun during the maiden test flight of the Falcon Heavy rocket is named "Starman" after the song.[78]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Molon, Dominic; Diederichsen, Diederich; Elms, Antony; Hell, Richard; Graham, Dan; Higgs, Matthew; Koether, Jutta; Nickas, Bob; Kelley, Mike; Tumlir, Jan (2007). Sympathy for the Devil: Art and Rock and Roll since 1967 (Illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-30013-426-1.

- ^ a b c d Pegg 2016, p. 461.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Cann 2010, p. 242.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 477.

- ^ Blum, Jordan (12 July 2012). "David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Doggett 2012, p. 169.

- ^ a b c d e f Pegg 2016, p. 462.

- ^ a b Buckley 1999, pp. 148–151.

- ^ Carr & Murray 1981, p. 44.

- ^ Copetas, Craig (28 February 1974). "Beat Godfather Meets Glitter Mainman: William Burroughs Interviews David Bowie". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 296.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 249.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 463.

- ^ Five Years (1969–1973) (Box set liner notes). David Bowie. UK, Europe & US: Parlophone. 2015. DBXL 1.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ O'Leary 2015, Partial Discography.

- ^ "Happy 43rd Birthday to Ziggy Stardust". David Bowie Official Website. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d Sheffield, Rob (6 July 2016). "How David Bowie Became the 'Starman'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Carr & Murray 1981, p. 8.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 460–461.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 247.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 256.

- ^ a b c d e Cann 2010, p. 258.

- ^ a b c Trynka 2011, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b Hepworth, David (15 January 2016). "How performing Starman on Top of the Pops sent Bowie into the stratosphere". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 460.

- ^ Jones, Dylan (2012). Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie and Four Minutes That Shook the World. Cornerstone. ISBN 978-1848093850.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 257.

- ^ a b Spitz 2009, p. 192.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 126.

- ^ "Bowie performs 'Starman' on 'Top of the Pops'". Seven Ages of Rock. BBC. 5 July 1972. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013.

- ^ Trynka 2011, pp. 197–198.

- ^ "David Bowie – Chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 127.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (3 July 2023), Why David Bowie Killed Ziggy Stardust, 50 Years Ago Today, Variety.com, retrieved 3 July 2023

- ^ Davis, Stephen (2021). Please Please Tell Me Now: The Duran Duran Story. New York City: Hachette Books. pp. 7–9, 12. ISBN 978-0-306-84606-9.

- ^ Pettigrew, Jason (23 January 2018). "Goth Inventors Bauhaus Recall the Night They Met David Bowie". AltPress. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 9.

- ^ Swanson, Dave (6 June 2017). "How David Bowie Created a Masterpiece with 'Ziggy Stardust'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Bowie at the Beeb: The Best of the BBC Radio Sessions 68–72 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Fortnam, Ian (11 November 2016). "Every song on David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust ranked from worst to best". Louder. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "David Bowie – The 100 Greatest Songs". Mojo. No. 255. February 2015. p. 81.

- ^ Barker, Emily (8 January 2018). "David Bowie's 40 greatest songs – as decided by NME and friends". NME. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (19 March 2020). "David Bowie's 50 greatest songs – ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Every David Bowie Single Ranked". Ultimate Classic Rock. 14 January 2016. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Q Magazine Lists". www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "4BC Official Top 40 - 15 December, 1972".

- ^ "Bangkok Single Chart, 19 August, 1972" (PDF).

- ^ "David Bowie – Starman" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 7665." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Euro Digital Song Sales)". Billboard. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin – levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava.

- ^ "David Bowie – Starman" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Starman". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ "Media Forest weekly chart (year 2016 week 02)". Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "David Bowie – Starman". Top Digital Download. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Japan Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Veckolista Heatseeker, vecka 2, 2016" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – David Bowie – Starman" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 30 December 2021. Select "2021" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "Starman" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Singoli" under "Sezione".

- ^ "Spanish single certifications – David Bowie – Starman". El portal de Música. Productores de Música de España. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "British single certifications – David Bowie – Starman". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 252.

- ^ "PREFACE:", Superman in Myth and Folklore, University Press of Mississippi, pp. XI–2, retrieved 3 November 2024

- ^ "Celebrating Superman", Superman in Myth and Folklore, University Press of Mississippi, 5 October 2017, ISBN 978-1-4968-1458-6, retrieved 3 November 2024

- ^ "'The Crown': Josh O'Connor, Erin Doherty on Charles and Anne 'Breaking the Mold'". 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ Newman, Melinda (2 October 2015). "Will the '70s Disco Soundtrack of 'The Martian' Be the Next 'Guardians of the Galaxy'?". Billboard. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Tyler, Adrienne (27 October 2021). "What Song Is In The Lightyear Trailer". Screen Rant. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Loftus, Johnny (1 June 2022). "Stream It Or Skip It: 'Pistol' on Hulu, A Riotously Visual, Danny Boyle-Directed Sex Pistols Biopic". Decider. NYP Holdings, Inc. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Cremona, Patrick (23 December 2022). "Glass Onion soundtrack: All the songs in the Knives Out sequel". Radio Times. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "David Bowie's 'Starman' Appears in Audi's Super Bowl 50 Ad". Billboard. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "Bleu de Chanel TV Commercial, 'Starman' Song by David Bowie". ispot.tv. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Starman (Vol. 2), #28

- ^ Robinson, Will (4 February 2016). "See Audi's Super Bowl commercial featuring David Bowie's 'Starman'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Emre Kelly, James Dean (7 February 2018). "Floating through space, SpaceX's 'Starman' mesmerizes the world". floridatoday.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Buckley, David (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-85227-784-0.

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croydon, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-38077-966-6.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York City: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (7th ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31603-225-4.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch