Stegotherium

| Stegotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

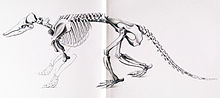

| Skeleton of Stegotherium tauberi (without carapace) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Cingulata |

| Family: | Dasypodidae |

| Subfamily: | Dasypodinae |

| Genus: | †Stegotherium Ameghino, 1887 |

| Type species | |

| †Stegotherium tessellatum Ameghino, 1887 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Stegotherium is an extinct genus of long-nosed armadillo, belonging to the Dasypodidae family alongside the nine-banded armadillo. It is currently the only genus recognized as a member of the tribe Stegotheriini. It lived during the Early Miocene of Patagonia and was found in Colhuehuapian rocks from the Sarmiento Formation, Santacrucian rocks from the Santa Cruz Formation,[2] and potentially also in Colloncuran rocks from the Middle Miocene Collón Curá Formation.[3] Its strange, almost toothless and elongated skull indicates a specialization for myrmecophagy, the eating of ants, unique among the order Cingulata, which includes pampatheres, glyptodonts and all the extant species of armadillos.[4]

History

[edit]Stegotherium tessellatum was described originally in 1887 by Florentino Ameghino based on the remains of a carapace collected by his brother Carlos in the Santa Cruz Province of Argentina. The same paper also described another genus and species of armadillo, Scaetops simplex, known from a fragmentary mandible.[5] In 1894, Stegotherium, at that time only known from osteoderms, was temporarily considered by Lydekker as a synonym of Peltephilus. This status was contested and proven wrong a year later by Ameghino.[citation needed]

In 1902, after a skull of Scaetops simplex was found in association with Stegotherium tessellatum osteoderms, Ameghino considered the two species synonymous, and proposed a new species Stegotherium variegatum based on osteoderms found in Chubut Province.[6] In 1904, after the discovery of additional remains of S. variegatum, William Berryman Scott re-evaluated Scaetops simplex as a species of Stegotherium different from S. tessellatum.[7]

In 2008, two important studies on the genus were published. The first, led by Fernicola and Vizcaíno, reviewed the material and species assigned to the genus. They proposed two new species, S. caroloameghinoi, with MACN-A 10443a, an osteoderm from the dorsal carapace, as holotype, and S. pascuali using MACN A-12680d, an osteoderm from the dorsal carapace, as holotype. This review also kept, not without some doubt, S. simplex as a valid taxon.[8] The second study from 2008, led by González Ruiz and Scillato-Yané, proposed ‘’Stegotherium tauberi’’ as a species, based on YPM PU 15565, a fairly complete specimen including a fragmentary dorsal carapace, a complete skull, several vertebra and a right foot, previously assigned to S. tessellatum.[1]

In 2009, another species was named by González Ruiz and Scillato-Yané, S. notohippidensis, with the holotype being MLP 84-III-5-10, a collection of 130 osteoderms from Argentina.[4]

Description

[edit]

Stegotherium was an unusual armadillo, whose most striking feature was the elongated skull, often compared to the skull of an anteater. The posterior area of the jaws, the only one to bear teeth, was compressed compared to Dasypus, while the nasal area and the anterior parts of both jaws, completely toothless, were long and slender. The teeth were cylindricals and greatly reduced, both in number and in size, and were all contained in the posterior area of the lower and upper jaws.[7] While S. tauberi had six teeth in its lower mandible, the dubious S. simplex only had two.[8]

The body of Stegotherium was roughly the size of the modern species of Dasypus,[5][8] and its carapace was composed of at least 23 mobile bands of osteoderms.[1] The osteoderms of Stegotherium, 3 to 7.5 mm thick[8] and 20 mm long,[6] were characterized by the presence of a number of piliferous foramina around their posterior and lateral margins, a granular appearance, and a compact bone structure.[9]

Species

[edit]The genus Stegotherium is unambiguously known from six species, S. tessellatum, S. variegatum, S. caroloameghinoi, S. pascuali, S. tauberi and S. notohippidensis. A seventh species, S. simplex, is generally considered too fragmentary, but has generally been considered valid with reservations by most recent scholars. As osteoderms are the most abundant fossils of Stegotherium known, they are commonly used as the main determinate of which species a given fossil belongs too.[citation needed]

Stegotherium tessellatum

[edit]S. tessellatum is the type species of Stegotherium.[5] Fossils of it have been recovered in the Santacrucian of the Santa Cruz Formation. It had quadrangular osteoderms, with a single large foramen in the exterior margin, devoid of longitudinal ridge of any kind in the central region. While non-osteoderm remains have been historically referred to this species in literature, they are now assigned to S. tauberi.[8]

Stegotherium simplex

[edit]S. simplex[5] is only known from its holotype, a fragmentary mandible with two alveoli, found in the Santa Cruz Formation and dated from the Santacrucian period. It is the only species in the genus whose osteoderms, usually considered diagnostic for armadillo fossils, are unknown. Its only diagnosis characteristic could be the presence of two molariform teeth on the mandible, while S. tessellatum had six;[10] the validity of the species has been debated since 1902,[8][1][4] and the holotype is probably lost.[10]

Stegotherium variegatum

[edit]S. variegatum is known from the Colhuehuapian Sarmiento Formation. The species is mainly known from fossilized quadrangular osteoderms, whose exposed surface showed several piliferous pits around a single granulated central figure, and a longitudinal ridge surrounded, in all of its length, by depressions.[8]

Stegotherium caroloameghinoi

[edit]S. caroloameghinoi is known from the Sarmiento Formation of Argentina, in rocks dating from the Colhuehuapian period. It is only known from osteoderms. Those were rectangular, with a granular textured dorsal surface. Piliferous pits are placed around a central figure, crossed by a median longitudinal ridge, and one to three smaller anterior figures.[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

The specific name, caroloameghinoi, is meant to honour Carlos Ameghino, who discovered the holotype of Stegotherium and was a prominent figure in the history of paleontology in Patagonia.[8]

Stegotherium pascuali

[edit]S. pascuali is known from the Colhuehuapian period in the Sarmiento Formation. It is known by fossilized osteoderms, whose various shapes all shared the same grainy-textured central figure surrounded by piliferous pits, without anterior figures. Two foramina, absent in S. variegatum and S. caroloameghinoi, and a ridge absent in S. tessellatum, were present on the osteoderms, completing the diagnostic characteristics.[8]

It was named to honour the Argentinian paleontologist Rosendo Pascual.[8]

Stegotherium tauberi

[edit]

S. tauberi is known from the Santa Cruz Formation, in rocks dated from the Santacrucian period. It is distinguished from other species of Stegotherium by osteoderms more rugged and with a sharper ridge than S. variegatum. Those osteoderms had a large foramen in the anterior-central region, along with several smaller foramina assembled in a transversal row in the anterior region. The presence of a longitudinal ridge on the osteoderms also distinguishes them. Some of the non-osteoderm material used by González Ruiz and Scillato-Yané to describe S. tauberi was assigned by Fernicola and Vizcaíno to S. tessellatum; both species are, however, considered valid by the current consensus.[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

Its species name, tauberi, honours Adán Alejo Tauber, an Argentinian paleontologist who worked on the Santa Cruz Formation.[1]

Stegotherium notohippidensis

[edit]S. notohippidensis is found in sediments from the "Notohippidian" period (traditionally considered as the lower part of the Santacrucian period) of the Santa Cruz Formation. Its osteoderms had several foramina in their anterior region, larger than S. variegatum and S. tauberi. In addition, the longitudinal ridge present in the osteoderms of other species of Stegotherium was absent in S. notohippidensis.[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

The species name, "notohippidensis" means, in Neo-Latin, "from the Notohippidian", which was itself named after the large herbivore Notohippus, considered to be characteristic of this period.[4]

Paleoecology

[edit]

The morphology of the jaws of Stegotherium shows that most of the mastication muscles were specialized for a horizontal and propalinal movement; the teeth were reduced but could still be used for masticating relatively soft food. Those important specializations pushed most scholars to consider Stegotherium as a specialized myrmecophage, similar ecologically to anteaters and to the less specialized giant armadillo.[7]

The area where Stegotherium lived was, during the Early Miocene, a forested savannah with a mild climate.[7] It lived alongside a diversity of related cingulates, such as the Euphractine Prozaedyus, the basal Chlamyphorid Proeutatus, the Dasypodid Stenotatus, the horned armadillo Peltephilus and several genera of glyptodonts, such as Asterostemma, Propalaehoplophorus, Cochlops and Eucinepeltus.[11]

The specialisation of Stegotherium may have caused the extinction of the genus during the Santacrucian, as it may have suffered from the large-scale environmental and climatic changes occurring in Patagonia during this period, the result of the rise of the Andes, causing an aridization that may have caused the rarefaction of ant and termite colonies it fed upon, and cooling making it harder for the animal to regulate its own body temperature.[7] After the Santacrucian, the genus is only known by one Colloncuran fossilized osteoderm, MLP 91-IV-1-66 from the Collón Curá Formation, tentatively assigned to Stegotherium sp. and different from all currently known species of Stegotherium, although other Colloncuran osteoderms of indeterminate Stegotheriini have also been recovered in the Chubut Province.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e González Laureano Raúl, Scillato-Yané Gustavo Juan. Una nueva especie de Stegotherium Ameghino (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae, Stegotheriini) del Mioceno de la provincia de Santa Cruz (Argentina). Ameghiniana, 2008 Dic; 45(4): 641-648.

- ^ Stegotherium at Fossilworks.org

- ^ a b Gonzalez-Ruiz, Laureano (October 2010). 1. Los Cingulata (Mammalia, Xenarthra) del Mioceno temprano y medio de Patagonia (edades Santacrucense y "Friasense"). Revisión sistemática y consideraciones bioestratigráficas (Doctor). Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

- ^ a b c d González Ruiz, L. R. L.; Scillato-Yané, G. J. (2009). "A new Stegotheriini (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) from the "Notohippidian" (early Miocene) of Patagonia, Argentina". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 252: 81–90. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2009/0252-0081. hdl:11336/95016.

- ^ a b c d Ameghino, F. (1887). "Enumeracion sistematica de las especies de mamiferos fosiles coleccionados por Carlos Ameghino en los terrenos eocenos de la Patagonia austral y depositados en el Museo La Plata". Boletin del Museo la Plata. 1: 1–26.

- ^ a b Ameghino, F. (1902). "Première contribution a la connaissance de la faune mammalogique des couches a Colpodon". Boletin de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias en Córdoba, República Argentina. 17: 71–141.

- ^ a b c d e Vizcaíno, S.F. (1994). "Mecánica masticatoria de Stegotherium tessellatum Ameghino (Mammalia, Xenarthra) del Mioceno temprano de Santa Cruz (Argentina). Algunos aspectos paleoecológicos relacionados". Ameghiniana. 231 (3): 283–290.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fernicola, J.C.; Vizcaíno, S.F. (2008). "Revisión del género Stegotherium Ameghino, 1887 (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Dasypodidae)". Ameghiniana. 245 (2): 321–332.

- ^ Ciancio, M.R.; Krmpotic, C.M.; Scarano, A.C.; Epele, M.B. (2019). "Internal Morphology of Osteoderms of Extinct Armadillos and Its Relationship with Environmental Conditions". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 26 (1): 71–93. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9404-y. S2CID 39630502.

- ^ a b Fernicola, J.C.; Vizcaíno, S.F. (2019). "Cingulates (Mammalia, Xenarthra) of the Santa Cruz Formation (Early-Middle Miocene) from the Rio Santa Cruz, Argentine Patagonia". Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina. 19 (2): 85–101.

- ^ Vizcaíno, S. F.; Kay, R.F.; Bargo, M. S. (2012). "Paleobiology of Santacrucian glyptodonts and armadillos (Xenarthra, Cingulata)". In Vizcaíno, S. F.; Kay, R. F.; Bargo, M. S. (eds.). Early Miocene Paleobiology in Patagonia: high-latitude paleocommunities of the Santa Cruz Formation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–215. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511667381. ISBN 9780511667381.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch