Withdrawal (military)

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

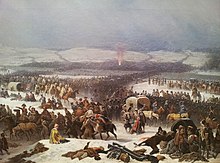

A tactical withdrawal or retreating defensive action is a type of military operation, generally meaning that retreating forces draw back while maintaining contact with the enemy. A withdrawal may be undertaken as part of a general retreat, to consolidate forces, to occupy ground that is more easily defended, force the enemy to overextend to secure a decisive victory, or to lead the enemy into an ambush. It is considered a relatively risky operation, requiring discipline to keep from turning into a disorganized rout or at the very least doing severe damage to the military's morale.

Tactical withdrawal

[edit]A withdrawal may be anticipated, as when a defending force is outmatched or on disadvantageous ground, but it must cause as much damage to an enemy as possible. In such a case, the retreating force may use a number of tactics and strategies to further impede the enemy's progress. That could include setting mines or booby traps during or before the withdrawal, leading the enemy into prepared artillery barrages, or using of scorched-earth tactics.

Rout

[edit]In warfare, the long-term objective is the defeat of the enemy. An effective tactical method is the demoralisation of the enemy by defeating its army and routing it from the battlefield. Once a force has become disorganized and has lost its ability to fight, the victors can chase down the enemy's remnants and attempt to cause as many casualties or to take as many prisoners as possible.

However, a commander must weigh the advantages of pursuit of a disorganised enemy against the possibility that the enemy may rally and leave the pursuing force vulnerable, with longer lines of communications that are vulnerable to a counterattack. That causes the value of a feigned retreat.

Feigned retreat

[edit]The act of feigning a withdrawal or rout to lure an enemy away from a defended position or into a prepared ambush is an ancient tactic, which has been used throughout the history of warfare.

Three famous examples are:

- William the Conqueror used a feigned retreat at the Battle of Hastings to lure much of Harold's infantry from their advantageous defenses on higher ground, leading to its annihilation by a charge of William's Norman cavalry.[1]

- Medieval Mongols were famed for, among other things, their extensive use of feigned retreats during their conquests, as their fast light cavalry made successful pursuit by an enemy almost impossible. In the heat and muddle of a battle, the Mongol Army would pretend to be defeated, exhausted and confused, and would suddenly retreat from the battlefield. The opposing force, thinking that it had routed the Mongols, would give chase. The Mongol cavalry would, while retreating, fire upon its pursuers and dishearten them (see Parthian shot).[2] When the pursuing forces stopped chasing the (significantly faster) Mongol cavalry, the Mongols would then turn and charge the pursuers and generally succeed. That was used partly as a defeat in detail tactic to allow the Mongols to defeat larger armies by breaking them into smaller groups.

- Early on during the Battle of Kasserine Pass in 1943, tanks of the US 1st Armored Division followed what appeared to be a headlong retreat by elements of the 21st Panzer Division. The advancing US forces then met a screen of German anti-tank guns, who opened fire and destroyed nearly all the American tanks. A US forward artillery observer, whose radio and landlines had been cut by shellfire, recalled:

It was murder. They rolled right into the muzzles of the concealed eighty-eights and all I could do was stand by and watch tank after tank blown to bits or burst into flames or just stop, wrecked. Those in the rear tried to turn back but the eighty-eights seemed to be everywhere.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Marren, Peter (2004). 1066: The Battles of York, Stamford Bridge & Hastings. Grub Street Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 9781783460021. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ An Heroical Epistle of Hudibras to His Lady, e-text, at exclassics.com

- ^ Westrate, Edwin V. (1944). Forward Observer. Philadelphia: Blakiston. pp. 109–117.

External links

[edit]- Barton, James. "Tactical Reasons for Retreat". Retrieved 2021-05-06.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch