Joseph Merrick

Joseph Merrick | |

|---|---|

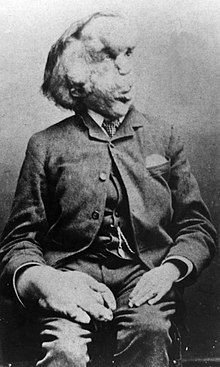

Merrick, c. 1889 | |

| Born | Joseph Carey Merrick 5 August 1862 Leicester, England |

| Died | 11 April 1890 (aged 27) London Hospital, Whitechapel, London, England |

| Resting place | Skeleton on display in Royal London Hospital. Soft tissue buried at the City of London Cemetery and Crematorium |

| Other names | The Elephant Man John Merrick |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Years active | 1884–1885 |

| Known for | Physical deformities due to suspected Proteus syndrome |

| Height | 5 ft 2 in (157 cm) |

Joseph Carey Merrick (5 August 1862 – 11 April 1890) was an English man known for his severe physical deformities. He was first exhibited at a freak show under the stage name "The Elephant Man", and then went to live at the London Hospital, in Whitechapel, after meeting Sir Frederick Treves, subsequently becoming well known in London society.

Merrick was born in Leicester and began to develop abnormally before the age of five. His mother died when he was eleven,[1] and his father soon remarried. Rejected by his father and stepmother, he left home and went to live with his uncle, Charles Merrick.[2] In 1879, 17-year-old Merrick entered the Leicester Union Workhouse.[3] In 1884, he contacted a showman named Sam Torr and proposed that he might be exhibited. Torr arranged for a group of men to manage Merrick, whom they named "the Elephant Man". After touring the East Midlands, Merrick travelled to London to be exhibited in a penny gaff shop rented by showman Tom Norman. The shop was visited by surgeon Frederick Treves, who invited Merrick to be physically examined. Merrick was displayed by Treves at a meeting of the Pathological Society of London in 1884,[4] after which Norman's shop was closed by the police.[5] Merrick then joined Sam Roper's circus and then toured in Europe by an unknown manager.[6]

In Belgium, Merrick was robbed by his road manager and abandoned in Brussels. He eventually made his way back to the London Hospital,[7] where he was allowed to stay for the rest of his life. Treves visited him daily, and the pair developed a close friendship. Merrick also received visits from some of the wealthy ladies and gentlemen of London society, including Alexandra, Princess of Wales. Although the official cause of his death was asphyxia, Treves, who performed the postmortem, concluded that Merrick had died of a dislocated neck.

The exact cause of Merrick's deformities is unclear, but in 1986 it was conjectured that he had Proteus syndrome. In a 2003 study, DNA tests on his hair and bones were inconclusive because his skeleton had been bleached numerous times before going on display at the Royal London Hospital. Merrick's life was depicted in a 1977 play by Bernard Pomerance and in a 1980 film by David Lynch, both titled The Elephant Man.

Early life and family

[edit]

Joseph Carey Merrick was born on 5 August 1862, at 50 Lee Street in Leicester, to Joseph Rockley Merrick and his wife Mary Jane (née Potterton).[8] Joseph Rockley Merrick (c. 1838–1897) was the son of London-born weaver Barnabas Merrick (1791–1856) who moved to Leicester during the 1820s or 1830s, and his third wife Sarah Rockley.[9] Mary Jane Potterton (c. 1837–1873), born at Evington in Leicestershire, was the daughter of William Potterton, who was described as an agricultural labourer in the 1851 census of Thurmaston, Leicestershire.[10] As a young woman, she worked as a domestic servant in Leicester before marrying Joseph Rockley Merrick, who at the time was a warehouseman,[11] in 1861.

Merrick was apparently healthy at birth, and he had no outward anatomical signs or symptoms of any disorder for the first few years of his life. Named after his father, he was given the middle name Carey by his mother, a Baptist, after the preacher William Carey.[12] The Merricks had two other children: William Arthur, born January 1866, who died of scarlet fever on 21 December 1870 aged four and was buried on Christmas Day 1870; and Marion Eliza,[13] born 28 September 1867, who had physical disabilities and died of myelitis and "seizures" on 19 March 1891, aged 23. William is buried with his mother, aunts and uncles in Welford Road Cemetery in Leicester;[14] Marion is buried with her father in Belgrave Cemetery in Leicester.[15]

Mary Jane's gravestone wrongly indicates that she had four children. It was originally understood that John Thomas Merrick (born 21 April 1864)—who died of smallpox on 24 July of the same year—was the fourth child of Joseph and Mary Jane Merrick, but the GRO birth records indicate that he was in fact not related to them.[16]

A pamphlet titled "The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick", produced c. 1884 to accompany his exhibition, states that he began to display anatomical signs at approximately five years of age, with "thick lumpy skin ... like that of an elephant, and almost the same colour".[17] According to a 1930 article in the Illustrated Leicester Chronicle, he began to develop swellings on his lips at the age of 21 months, followed by a bony lump on his forehead and a loosening and roughening of the skin.[18][nb 1] As he grew, a noticeable difference between the size of his left and right arms appeared, and both his feet became significantly enlarged.[18] The Merrick family explained his symptoms as the result of Mary Jane being knocked over and frightened by a fairground elephant while she was pregnant with him.[18] The concept of maternal impression—that the emotional experiences of pregnant women could have lasting physical effects on their unborn children—was still common in 19th-century Britain.[20] Merrick held this belief about the cause of his disability throughout his life.[21]

In addition to his deformities, Merrick fell and damaged his left hip at some point during his childhood. The injury site became infected and left him permanently disabled.[22] Although limited by his physical deformities, Merrick attended school and enjoyed a close relationship with his mother.[22] She was a Sunday school teacher, and his father worked as an engine driver at a cotton factory, as well as running a haberdashery business.[22] Mary Jane Merrick died from bronchopneumonia on 29 May 1873, two and a half years after the death of her youngest son William.[1] Joseph Rockley Merrick moved with his two surviving children to live with Mrs. Emma Wood Antill, a widow with children of her own. They married on 3 December 1874.[23]

Employment and the workhouse

[edit]I was taunted and sneered at so that I would not go home to my meals, and used to stay in the streets with a hungry belly rather than return for anything to eat, what few half-meals I did have, I was taunted with the remark—"That's more than you have earned."

Merrick left school aged 13, which was usual for the time.[24] His home life was now "a perfect misery",[17] and neither his father nor his stepmother demonstrated affection toward him.[23] He ran away "two or three" times, but was taken back by his father each time.[17] At 13, he found work rolling cigars in a factory, but after three years, the deformity of his right hand had worsened to the extent that he no longer had the dexterity required for the job.[24] Now unemployed, he spent his days wandering the streets, looking for work and avoiding his stepmother's taunts.[8]

As Merrick was becoming a greater financial burden on his family, his father eventually secured him a hawker's licence enabling him to earn money selling items from the haberdashery shop, door to door.[25] This endeavour was unsuccessful because Merrick's facial deformities rendered his speech increasingly unintelligible, and prospective customers reacted with horror to his physical appearance. People refused to open the door to him, and they not only stared at him, but followed him out of curiosity.[25] Merrick failed to make enough money as a hawker to support himself. On returning home one day in 1877, he was severely beaten by his father and he left home for good.[26]

Merrick was now homeless on the streets of Leicester. His uncle, a barber named Charles Merrick, on hearing of his nephew's situation, sought him out and offered him accommodation in his home.[27] Merrick continued to hawk around Leicester for the next two years but his efforts to earn a living met with little more success than before. Eventually, his disfigurement drew such negative attention from members of the public that the Commissioners for Hackney Carriages withdrew his licence when it came up for renewal.[27] With young children to provide for, Charles could no longer afford to support his nephew. In late December 1879, now 17 years old, Merrick entered the Leicester Union Workhouse.[28]

One of 1,180 residents in the workhouse,[29] Merrick was given a classification to determine his place of accommodation. The class system specified the department or ward in which a resident would reside, as well as the amounts of food received. Merrick was classified as Class One for able-bodied people.[29] On 22 March 1880, only 12 weeks after entering the workhouse, Merrick signed himself out and spent two days looking for work. With no more success than before, he found himself with no option but to return to the workhouse. This time, he stayed for four years.[30]

Around 1882, Merrick underwent surgery on his face. The protrusion from his mouth had grown to 20–22 centimetres, severely inhibiting his speech and making it difficult to eat.[31] The operation was performed in the Workhouse Infirmary under the direction of Dr Clement Frederick Bryan, during which a large part of the mass was removed.[32]

Life as a curiosity

[edit]Merrick concluded that his only escape from the workhouse might be through the world of human novelty exhibitions.[33][34] He wrote a speculative letter to Sam Torr, a Leicester music hall comedian and proprietor that he knew. Torr came to visit Merrick at the workhouse and decided he could make money exhibiting him; although, to retain Merrick's novelty value, he would need to be put on display as a travelling exhibit.[33] To this end, Torr organised a group of managers for his new charge: music hall proprietor J. Ellis, travelling showman George Hitchcock, and fair owner Sam Roper. On 3 August 1884, Merrick departed the workhouse to start his new career.[35]

The showmen named Merrick the Elephant Man and advertised him as "Half-a-Man and Half-an-Elephant".[35] They showed him around the East Midlands, including in Leicester and Nottingham, before moving him on to London for the winter season. Hitchcock contacted an acquaintance, showman Tom Norman, who ran penny gaff shops in the East End of London exhibiting human curiosities. Without the need for a meeting, Norman agreed to take over Merrick's management, and Merrick travelled with Hitchcock to London in November 1884.[36]

When Norman first encountered Merrick, he was dismayed by the extent of his deformities, fearing his appearance might be too horrific to be a successful novelty.[37] Nevertheless, he exhibited Merrick in the back of an empty shop on Whitechapel Road. Merrick slept on an iron bed with a curtain drawn around to afford him some privacy. Observing Merrick asleep one morning, Norman learnt that he always slept sitting up, with his legs drawn up and his head resting on his knees. His enlarged head was too heavy to allow him to sleep lying down and, as Merrick put it, he would risk "waking with a broken neck".[38] Norman decorated the shop with posters that Hitchcock had produced, depicting a monstrous half-man, half-elephant.[39] A pamphlet was created, titled "The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick", giving an outline of Merrick's life to date. This brief biography, whether written by Merrick or not, provided a generally accurate account of his life. It did contain an incorrect date of birth, but Merrick was always vague about when exactly he was born.[40]

Ladies and gentlemen ... I would like to introduce Mr Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man. Before doing so I ask you please to prepare yourselves—Brace yourselves up to witness one who is probably the most remarkable human being ever to draw the breath of life.

Norman gathered an audience by standing outside the shop and attracting passers-by with his showman's patter. He would then lead the assembled crowd into the shop, explaining that the Elephant Man was "not here to frighten you but to enlighten you".[39] Pulling the curtain to one side, he allowed the onlookers—often visibly horrified—to observe Merrick up close, while describing the circumstances that had led to his present condition, including his mother's alleged incident with a fairground elephant.

The Elephant Man exhibit was moderately successful, and made money primarily from the sales of the autobiographical pamphlet.[38] Merrick was able to put his share of the profits aside, in the hope of earning enough money to one day buy a home of his own.[42] The shop on Whitechapel Road was directly opposite the London Hospital, ideally situated for medical students and doctors to visit, curious to see Merrick.[38] One such visitor was a young house surgeon named Reginald Tuckett, who, like his colleagues, was intrigued by the Elephant Man's deformities. Tuckett suggested that his senior colleague Frederick Treves should pay Merrick a visit.[43]

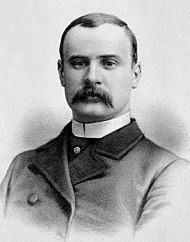

Treves first met Merrick that November, at a private viewing that took place before Norman opened the shop for the day.[38] Treves later recalled in his 1923 Reminiscences that Merrick was "the most disgusting specimen of humanity that I had ever seen [...] at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed."[44] The viewing lasted no more than 15 minutes, after which Treves returned to work. Later the same day, he sent Tuckett back to the shop to ask if Merrick might be willing to go to the hospital for an examination. Norman and Merrick both agreed to the request.[45] To allow him to travel the short distance without drawing undue attention, Merrick wore a disguise consisting of an oversized black cloak and a brown cap with a hessian sack covering his face, and he rode in a cab hired by Treves.[46] Although Treves stated that Merrick's outfit on this occasion included the black cloak and brown cap, there is evidence to suggest that Merrick acquired that particular costume a year later, while travelling with Sam Roper's Fair. If that were the case, Treves was remembering the clothing from a later meeting with Merrick.[47]

On examining Merrick at the hospital, Treves observed that he was "shy, confused, not a little frightened, and evidently much cowed".[44] At this point, Treves assumed him to be an "imbecile".[44] He measured Merrick's head circumference at the enlarged size of 36 inches (91 cm), his right wrist at 12 inches (30 cm) and one of his fingers at 5 inches (13 cm) in circumference. He noted that Merrick's skin was covered in papillomata (warty growths), the largest of which exuded an unpleasant smell.[48] The subcutaneous tissue appeared to be weakened, causing a loosening of the skin which, in some areas, hung away from the body. There were bone deformities in the right arm, both legs, and, most conspicuously, in the large skull.[49] Despite having had corrective surgery to his mouth in 1882, Merrick's speech remained barely intelligible. His left arm and hand were neither enlarged nor deformed. His penis and scrotum were normal. Apart from his deformities and the lameness in his hip, Treves concluded that Merrick appeared to be in good general health.[50]

Norman later recalled that Merrick had visited the hospital "two or three" times,[45] and that Treves had given Merrick his calling card during one of those visits.[8] Treves had some photographs taken on one occasion, and provided Merrick with a set of copies which were later added to his autobiographical pamphlet.[51] On 2 December 1884, Treves presented Merrick at a meeting of the Pathological Society of London in Bloomsbury.[52] Merrick eventually told Norman that he no longer wanted to be examined at the hospital. According to Norman, he said he was "stripped naked and felt like an animal in a cattle market".[53]

During this period in Victorian Britain, tastes were changing in regard to freak show exhibitions like Norman's, which were becoming a cause for public concern on the grounds of decency and because of the disruption caused by crowds gathering outside them.[54] Shortly after Merrick's last examination with Treves, the police closed down Norman's shop on Whitechapel Road, and Merrick's Leicester managers withdrew him from Norman's charge.[53] In 1885, Merrick went on the road with Sam Roper's travelling fair.[55] He befriended two other performers, known as "Roper's Midgets"—Bertram Dooley and Harry Bramley—who occasionally defended Merrick from public harassment.[47]

Europe

[edit]As the dampening of public enthusiasm for freak shows and human oddities continued, the police and magistrates became increasingly vigilant in closing down shows. Merrick remained a horrifying spectacle for his viewers, but Roper grew nervous about the negative attention he was drawing from local authorities.[47] Merrick's group of managers decided he should go on tour in continental Europe, with the hope that the authorities there would be more lenient. His management was assumed by an unknown man (possibly named Ferrari) and they left for the continent.[56]

Merrick was no more successful in continental Europe than he had been in Britain, and similar action was taken by the authorities to move him out of their jurisdictions. In Brussels, Merrick was deserted by his new manager, who stole his £50 (equivalent to about £6,900 in 2023) savings.[57] Abandoned and penniless, Merrick made his way by train to Ostend, where he attempted to board a ferry for Dover, but was refused passage.[58] He travelled to Antwerp, and was able to board a ship bound for Harwich in Essex. From there, he travelled by train to London and arrived at Liverpool Street station.[59]

Merrick reached London on 24 June 1886, safely back in his own country but with nowhere to go. He was not eligible to enter a workhouse in London for more than one night, and the only place that would accept him was the Leicester Union Workhouse (where he was to become a permanent resident), but Leicester was 98 miles (158 km) away.[60]

He approached strangers for help, but his speech was unintelligible and his appearance repugnant. After drawing a crowd of curious onlookers, Merrick was helped by a policeman into an empty waiting room, where he huddled in a corner, exhausted. Unable to make himself understood, his only identifying possession was Treves's card.[61]

The police contacted Treves, who went to the train station and, on recognising Merrick, took him in a hansom cab to the London Hospital. Merrick was admitted for bronchitis, washed, fed and then put to bed in a small isolation room in the hospital's attic.[62]

London Hospital

[edit]

With Merrick admitted into the hospital, Treves now had time to conduct a more thorough examination. He discovered that Merrick's physical condition had deteriorated over the previous two years and that he had become impaired by his deformities. Treves also suspected that Merrick had a heart condition and had only a few years left to live.[63] Merrick's general health improved over the next five months under the care of the hospital staff. Although some nurses were initially upset by his appearance, they were able to overcome this and take care of him.[64]

The problem of Merrick's unpleasant odour was mitigated through frequent bathing, and Treves gradually developed an understanding of his speech. A new set of photographs was taken. Francis Carr Gomm, the chairman of the hospital committee, had supported Treves in his decision to admit Merrick, but it was clear by November that long-term care plans were needed. The London Hospital was not equipped or staffed to provide care for the incurable, which Merrick clearly was.[64]

Carr Gomm contacted other institutions and hospitals more suited to caring for chronic cases, but none would accept Merrick. Gomm wrote a letter to The Times, printed on 4 December 1886, outlining Merrick's case and asking readers for suggestions.[65] The public response—in letters and donations—was significant, and the situation was even covered by the British Medical Journal.[66] With the financial backing of the many donors, Gomm was able to make a convincing case to the committee for keeping Merrick in the hospital. It was decided that he would be allowed to stay there for the remainder of his life.[67] He was moved from the attic to the basement, where he could occupy two rooms adjacent to a small courtyard. The rooms were adapted and furnished to suit Merrick, with a specially constructed bed and—at Treves's instruction—no mirrors.[68]

Merrick settled into his new life at the London Hospital. Treves visited him daily and spent a couple of hours with him every Sunday.[69] Now that Merrick had found someone who understood his speech, he was delighted to carry on long conversations with the doctor.[69] Treves and Merrick built a friendly relationship, although Merrick never completely confided in him. He told Treves that he was an only child, and Treves had the impression that his mother, whose picture Merrick always carried with him, had abandoned him as a baby.[69] Merrick was also reluctant to talk about his exhibition days, although he expressed gratitude towards his former managers.[70] It did not take Treves long to realise that, contrary to his initial impressions, Merrick was not intellectually impaired.[69]

Treves observed that Merrick was very sensitive and showed his emotions easily.[71] At times, Merrick was bored and lonely, and demonstrated signs of depression.[72] He had spent his entire adult life segregated from women, first in the workhouse and then as an exhibit. The women he met were either disgusted or frightened by his appearance.[73] His opinions about women were derived from his memories of his mother and what he read in books. Treves decided that Merrick would like to be introduced to a woman and it would help him feel normal.[74] The doctor arranged for a friend of his named Mrs. Leila Maturin, "a young and pretty widow", to visit Merrick.[44] She agreed and with fair warning about his appearance, she went to his rooms for an introduction. The meeting was short, as Merrick quickly became overcome with emotion.[74] He later told Treves that Maturin had been the first woman ever to smile at him, and the first to shake his hand.[44] She kept in contact with him and a letter written by Merrick to her, thanking her for the gift of a book and a brace of grouse, is the only surviving letter written by Merrick.[75] This first experience of meeting a woman, though brief, instilled in Merrick a new sense of self-confidence.[76] He met other women during his life at the hospital, and appeared taken with them all. Treves believed that Merrick's hope was to one day live at an institution for the blind, where he might meet a woman who could not see his deformities.[76]

Merrick wanted to know about the "real world", and questioned Treves on a number of topics. On one occasion, he expressed a desire to see inside what he considered a "real" house and Treves obliged, taking him to visit his Wimpole Street townhouse and meet his wife.[77] At the hospital, Merrick spent his days reading and constructing models of buildings out of card. He entertained visits from Treves and his house surgeons. He rose each day in the afternoon and would leave his rooms to walk in the small adjacent courtyard, after dark.

As a result of Carr Gomm's letters to The Times, Merrick's case attracted the notice of London's high society. One person who took a keen interest was actress Madge Kendal.[78] Although she probably never met him in person, she was responsible for raising funds and public sympathy for Merrick.[79] She sent him photographs of herself and employed a basket weaver to go to his rooms and teach him the craft.[80] Other people of high society did visit him, however, bringing gifts of photographs and books. He reciprocated with letters and handmade gifts of card models and baskets. Merrick enjoyed these visits and became confident enough to converse with people who passed his windows.[81] A young man, Charles Taylor, the son of the engineer responsible for modifying Merrick's rooms, spent time with him, sometimes playing the violin.[79] Occasionally, Merrick grew bold enough to leave his small living quarters and explore the hospital. When discovered, he was always hurried back to his quarters by the nurses, who feared he might frighten the patients.[81]

On 21 May 1887, two new buildings were completed at the hospital and the Prince and Princess of Wales came to open them officially.[82] The princess wished to meet the Elephant Man, so after a tour of the hospital, the royal party went to his rooms for an introduction. Princess Alexandra shook Merrick's hand and sat with him, an experience that left him overjoyed.[83] She gave him a signed photograph of herself, which became a prized possession, and she sent him a Christmas card each year.[44]

On at least one occasion, Merrick was able to fulfill a long-held desire to visit the theatre.[84] Treves, with the help of Madge Kendal, arranged for him to attend the Christmas pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Merrick sat with some nurses, concealed in Lady Burdett-Coutts' private box.[85] According to Treves, Merrick was "awed" and "enthralled", and "[the] spectacle left him speechless, so that if he were spoken to he took no heed."[44] Merrick talked about the pantomime for weeks afterwards, reliving the story as if it had been real.[86]

Last years

[edit]On three occasions, Merrick left the hospital to go on holiday, spending a few weeks at a time in the countryside.[87] By means of elaborate arrangements that allowed him to board a train unseen and have an entire carriage to himself, Merrick travelled to Northamptonshire to stay at Fawsley Hall, the estate of Lady Knightley.[87] He stayed at the gamekeeper's cottage and spent the days walking in the estate's woods, collecting wild flowers.[88] He befriended a young farm labourer who later recalled Merrick as an interesting and well-educated man.[75] Treves called this "the one supreme holiday of [Merrick's] life", although in fact there were three such trips.[44][89]

Merrick's condition gradually deteriorated during his four years at the London Hospital. He required a great deal of care from the nursing staff and spent much of his time in bed, or sitting in his quarters, with diminishing energy.[75] His facial deformities continued to grow and his head became more enlarged. He died on 11 April 1890, while sleeping, at the age of 27.[90] At around 3:00 p.m. Treves's house surgeon visited Merrick and found him lying dead across the bed. His body was formally identified by his uncle, Charles Merrick.[91] An inquest was held on 27 April by Wynne Edwin Baxter, who had gained notoriety conducting inquests for the Whitechapel murders of 1888.[90]

He often said to me that he wished he could lie down to sleep 'like other people' ... he must, with some determination, have made the experiment ... Thus it came about that his death was due to the desire that had dominated his life—the pathetic but hopeless desire to be 'like other people'.

Merrick's death was ruled accidental and the certified cause of death was asphyxia, resulting from the weight of his head as he lay down.[92][93] After performing an autopsy, Treves determined that Merrick had died of a dislocated neck, which likely severed his vertebral arteries.[93] Knowing that Merrick had always slept sitting upright out of necessity, Treves concluded that Merrick must have "made the experiment", attempting to sleep lying down "like other people".[44][93]

Merrick did not receive a burial; instead, almost all sections of his body were preserved for study, both skeleton and soft tissue. Treves dissected the body and took plaster casts of Merrick's head and limbs. He took skin samples and mounted the skeleton; the skin samples were later lost during the Second World War, but the skeleton is included in the pathology collection of the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel,[94] which merged with the Medical College of St Bartholomew's Hospital in 1995 to form the School of Medicine and Dentistry at London's Queen Mary University.[95] Merrick's mounted skeleton is not on public display.[96][97]

His remains are kept in a glass case in a private room at the university, and can be viewed by medical students and professionals by appointment "[to] allow medical students to view and understand the physical deformities resulting from Joseph Merrick's condition." Although the university intends to keep his skeleton at its medical school, some contend that, as Merrick was a devout Christian, he should be given a Christian burial in his home city of Leicester.[98][99][100]

On 5 May 2019, author Jo Vigor-Mungovin discovered that Merrick's soft tissue was buried in the City of London Cemetery.[101]

Medical condition

[edit]

Ever since Merrick's days as a novelty exhibit on Whitechapel Road, his condition has remained a source of curiosity for medical professionals.[102] His appearance at the meeting of the Pathological Society of London in 1884 drew interest from the doctors present, but gained neither the answers nor the wider attention that Treves had hoped for. The case received only a brief mention in the British Medical Journal, while the Lancet declined to mention it at all.[103]

Four months later, in 1885, Treves brought the case before the meeting for a second time. By then, Tom Norman's shop on Whitechapel Road had been closed down and Merrick had moved on, so in Merrick's absence, Treves made do with the photographs he had taken during his examinations. One of the doctors present at the meeting was Henry Radcliffe Crocker, a dermatologist who was an authority on skin diseases.[104] After hearing Treves's description of Merrick, and viewing the photographs, Crocker proposed that Merrick's condition might be a combination of pachydermatocele and an unnamed bone deformity, all caused by changes in the nervous system.[54] Crocker wrote about Merrick's case in his 1888 book Diseases of the Skin: their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment.[105]

In 1909, dermatologist Frederick Parkes Weber wrote an article in the British Journal of Dermatology,[106] incorrectly citing Merrick as an example of von Recklinghausen Disease (neurofibromatosis), which German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen had described in 1882.[107] This conjecture has since been proved wrong; in fact, symptoms that are always present in this genetic disorder include tumours of the nervous tissue and bones, small warty growths on the skin,[108] and the presence of light brown pigmentation on the skin called café au lait spots, which are of particular importance in diagnosing von Recklinghausen Disease,[109] but which were never observed on Merrick's body.[110] For this reason, although the diagnosis was quite popular through most of the 20th century, other conjectural diagnoses were advanced, such as Maffucci syndrome and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (Albright's disease).[110]

In a 1986 article in the British Medical Journal, Michael Cohen and J. A. R. Tibbles put forward the hypothesis that Merrick had had Proteus syndrome, a very rare congenital disorder identified by Cohen in 1979, citing Merrick's lack of reported café au lait spots and the absence of any histological proof of his having had the previously conjectured syndrome.[111] In fact, Proteus syndrome affects tissue other than nerves, and is a sporadic disorder rather than a genetically transmitted disease.[112] Cohen and Tibbles said Merrick showed the following signs of Proteus syndrome: "macrocephaly; hyperostosis of the large skull; hypertrophy of long bones; and thickened skin and subcutaneous tissues, particularly of the hands and feet, including plantar hyperplasia, lipomas, and other unspecified subcutaneous masses".[111]

In a letter to The Biologist in June 2001, British teacher and Chartered Biologist Paul Spiring[113] speculated that Merrick might have had a combination of Proteus syndrome and neurofibromatosis. This hypothesis was reported by Robert Matthews, a correspondent for The Sunday Telegraph.[114] The possibility that Merrick may have had both conditions formed the basis for a 2003 documentary film entitled The Curse of The Elephant Man, which was produced for the Discovery Health Channel by Natural History New Zealand.[115][116]

During 2002, genealogical research for the film led to a BBC appeal to trace Merrick's maternal family line. In response to the appeal, a Leicester resident named Pat Selby was discovered to be the granddaughter of Merrick's uncle, George Potterton. A research team took DNA samples from Selby in an unsuccessful attempt to diagnose Merrick's condition.[117] During 2003, the filmmakers commissioned further diagnostic tests using DNA from Merrick's hair and bone, but the results of these tests proved inconclusive; therefore, the precise cause of Merrick's medical condition remains uncertain.[115][116][118]

Legacy

[edit]In 1923, Treves published a volume, The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, in which he detailed what he knew of Merrick's life and his personal interactions with him. This account is the source of much of what is known about Merrick, but the book contained several inaccuracies. Merrick had never completely confided in Treves about his early life, so these details were consequently sketchy in Treves's Reminiscences. A more mysterious error is that concerning Merrick's first name; Treves, in his earlier journal articles as well as his book, persisted in calling him John Merrick. The reason for this is unknown, as Merrick clearly signed his name as "Joseph" in the examples of his handwriting that remain.[119] In the handwritten manuscript for The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, Treves began his account by writing "Joseph" and then crossed it out and replaced it with "John".[120] Whatever the reason for the discrepancy, it continued throughout much of the 20th century; later biographers have perpetuated the error, having based their work on Treves's book.

Treves depicted Tom Norman, the showman who had exhibited Merrick on Whitechapel Road, as a cruel drunk who ruthlessly exploited his charge.[121][122] In a letter to the World's Fair newspaper, and later in his own memoirs, Norman denied this characterisation and said he provided his show attractions with a means to earn a living, adding that Merrick was still on display while residing at the London Hospital, but with no way of controlling how or when he was viewed. According to Nadja Durbach, author of The Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture (2010), Norman's view gives an insight into the Victorian freak show's function as a survival mechanism for poor people with deformities, as well as the attitude of medical professionals of the time.[123] Durbach cautions that the memoirs of both Treves and Norman must be understood as "narrative reconstructions ... that reflect personal and professional prejudices and cater to the demands and expectations of their very different audiences".[124]

In November 2016, Joanne Vigor-Mungovin published a book called Joseph: The Life, Times and Places of the Elephant Man, which included a foreword written by a member of Merrick's family. The book looks into the early life of Merrick and his family in Vigor-Mungovin's hometown of Leicester, with detailed information about Merrick's family and his ambition to be self-sufficient rather than survive on the charity of others.[125]

Anthropologist Ashley Montagu's book, The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity (1971), drew on Treves's book and explored Merrick's character.[126] Montagu reprinted Treves's account alongside various others, such as Carr Gomm's letter to The Times in December 1886 and the report on Merrick's inquest. He pointed out inconsistencies between the accounts and disputed some of Treves's version of events; he noted, for example, that while Treves claimed Merrick knew nothing of his mother's appearance, Carr Gomm mentions that Merrick carried a painting of his mother with him,[127] and he criticised Treves's assumption that Merrick's mother was "worthless and inhuman".[127] However, Montagu also perpetuated some of the errors in Treves's work,[128] including his use of the name "John" rather than "Joseph".[127]

In 1980, Michael Howell and Peter Ford presented the findings of their detailed archival research in The True History of the Elephant Man, which revealed a large amount of new information about Merrick. Howell and Ford were able to provide a more detailed description of Merrick's life story, also proving that his name was actually Joseph, not John. They refuted some of the inaccuracies in Treves's account, showing that Merrick had not been abandoned by his mother, and that he had voluntarily chosen to exhibit himself to make a living.

'Tis true my form is something odd,

But blaming me is blaming God;

Could I create myself anew

I would not fail in pleasing you.

If I could reach from pole to pole

Or grasp the ocean with a span,

I would be measured by the soul;

The mind's the standard of the man.

Some persons remarked on Merrick's strong Christian faith (Treves is also said to have been a Christian), and that his strong character and courage in the face of disabilities earned him admiration.[129] Merrick's life story has become the subject of several works of dramatic art, based on the accounts of Treves and Montagu. The Elephant Man, a Tony Award-winning play by American playwright Bernard Pomerance, was staged in 1979.[130] The character based on Merrick was initially played by David Schofield,[131][132] and in subsequent productions by various actors including Philip Anglim, David Bowie, Bruce Davison, Mark Hamill and Bradley Cooper.[133] A biographical film, also titled The Elephant Man, was released in 1980; directed by David Lynch, it received eight Academy Award nominations. Merrick was played by John Hurt and Frederick Treves by Anthony Hopkins. In 1982, US television network ABC broadcast an adaptation of Pomerance's play, starring Anglim.[134]

In the 2001 film From Hell, Merrick, played by Anthony Parker, appears briefly.

American metal band Mastodon has three songs dedicated to Joseph Merrick - all of them are instrumental album closers: "Elephant Man" (from "Remission", 2002), "Joseph Merrick" (from "Leviathan", 2004), and "Pendulous Skin" (from "Blood Mountain", 2006).

Merrick is portrayed by actor Joseph Drake in two episodes of the second series of the BBC historical crime drama Ripper Street, first broadcast in 2013. In 2017, the Malthouse Theatre, Melbourne, commissioned playwright Tom Wright to produce a play about Merrick's life. The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man premiered on 4 August 2017, starring Daniel Monks in the title role. The cast also featured Paula Arundell, Julie Forsyth, Emma J. Hawkins, and Sophie Ross.[135] The play toured the UK in 2023, directed by Stephen Bailey and starring Zak Ford-Williams as Merrick.[136][137] This cast of this production included Annabelle Davies and Nadia Nadarajah, and off the back of this production, the play was published as a book.[138]

It was announced in August 2018 that Charlie Heaton would be playing Merrick in a new two-part BBC drama,[139] a decision that drew criticism from some quarters;[140] instead of re-casting a disabled actor, the production was subsequently cancelled. In the 2019 sitcom Year of the Rabbit, Merrick was played by David Dawson as a pretentious theatrical type.[141]

Merrick's life is the subject of Joseph Merrick, The Elephant Man, an opera by composer Laurent Petitgirard, set to a French libretto by Eric Nonn. Starring contralto Jana Sykorova in the title role, it premiered on 7 February 2002 at the State Opera House, Prague.[142]

References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ An article was published anonymously in the Illustrated Leicester Chronicle on 27 December 1930 which was, according to Howell & Ford (1992), "clearly based on a knowledge of the Merrick family circumstances". It included information about Merrick's mother's background, his early development and his attempts to gain employment.[19]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 61

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 77

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 83

- ^ Treves, Frederick (1923). The Elephant Man and other Reminiscences (2016 ed.). London: Thomas Anker. p. 2. ISBN 978-1493725380.

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 120

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 123

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 141

- ^ a b c Osborne, Peter; Harrison, B. (September 2004). "Merrick, Joseph Carey [Elephant Man] (1862–1890)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37759. Retrieved 24 May 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 33

- ^ The National Archives: HO107/2087, f.666, p.12

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 38

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 42

- ^ "New research on Elephant man". BBC News. 28 February 2003. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 58

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 79

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 59

- ^ a b c d e "The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick"

- ^ a b c Howell & Ford (1992), p. 43

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), pp. 32, 42, 50

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 129

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 128

- ^ a b c Howell & Ford (1992), p. 44

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 47

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 48

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 49

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 50

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 51

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 52

- ^ a b Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 88

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 57

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 58

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin (2016), p. 96

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 62

- ^ "Elephant Man – The Complete Story of Joseph Merrick". thehumanmarvels.com. 21 April 2008. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 63

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 64

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 72

- ^ a b c d Howell & Ford (1992), p. 75

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 73

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 53

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 74

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 78

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Treves (1923)

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 76

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 13

- ^ a b c Howell & Ford (1992), p. 81

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 23

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 24

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 25

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 79

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 26

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 77

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 29

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 80

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 84

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 85

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 86

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 87

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 88

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 89

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 90

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 94

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 95

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 93

- ^ "The "Elephant-Man"", British Medical Journal, 2 (1354): 1188–1189, 11 December 1886, doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1354.1171, S2CID 220141789

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 99

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 100

- ^ a b c d Howell & Ford (1992), p. 102

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 103

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 104

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 106

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 105

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 107

- ^ a b c Howell & Ford (1992), p. 145

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 108

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 114

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 109

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 111

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 112

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 113

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 115

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 116

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 119

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 120

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 126

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 142

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 143

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 144

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 146

- ^ "Death Of 'The Elephant Man'", The Times, p. 6, 16 April 1890

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 147

- ^ a b c Howell & Ford (1992), p. 151

- ^ Graham & Oehschlaeger (1992), p. 23

- ^ "University of London: Queen Mary University of London". lon.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Cahal Milmo (21 November 2002). "Scientists hope relative can help explain Elephant Man". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ "Joseph's Autobiography". Joseph Carey Merrick Tribute Website. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ Farley, Harry (10 June 2016). "'Elephant man' was a devout believer and should have Christian burial, say campaigners". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "'Elephant Man' Joseph Merrick 'should be buried in Leicester'". BBC News. 9 June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "'Elephant Man' skeleton deserves Christian burial, say campaigners". The Guardian. 9 June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "Elephant Man: Joseph Merrick's grave 'found by author'". BBC News. 5 May 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Deconstructing The Elephant Man: Mysteries Of Joseph Merrick's Deformities May Soon Be Unlocked". Medical Daily. 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 27

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 28

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 127

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 133

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 132

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 134

- ^ Korf & Rubenstein (2005), p. 61

- ^ a b Howell & Ford (1992), p. 137

- ^ a b Tibbles, J.A.R.; Cohen, M.M. (1986), "The Proteus syndrome: the Elephant Man diagnosed", British Medical Journal, 293 (6548): 683–685, doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6548.683, PMC 1341524, PMID 3092979.

- ^ Barry, Megan E. (13 June 2018), Rohena, Luis O. (ed.), "Proteus Syndrome", eMedicine.medscape.com, Medscape, archived from the original on 16 November 2018, retrieved 17 April 2023

- ^ "List of Current Fellows". Society of Biology. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Matthews, Robert (14 June 2001), "Two wrongs don't make a right — until someone joins them up", The Sunday Telegraph, archived from the original on 15 April 2010, retrieved 23 May 2010

- ^ a b "Elephant man mystery unravelled", BBC News, 21 July 2003, archived from the original on 9 July 2020, retrieved 23 May 2010

- ^ a b Highfield, Roger (22 July 2003), "Science uncovers handsome side of the Elephant Man", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 21 March 2021, retrieved 23 May 2010

- ^ "Elephant man's descendant found", BBC News, 20 November 2002, retrieved 2 June 2010

- ^ Bomford, Andrew (29 August 2013). "Unlocking the secrets of the Elephant Man". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 7

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 164

- ^ Toulmin, Vanessa; Harrison, B. (January 2008). "Norman, Tom (1860–1930)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73081. Retrieved 19 June 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Toulmin, Vanessa (2007), "'It was not the show it was the tale that you told': The Life and Legend of Tom Norman, the Silver King", National Fairground Archive, University of Sheffield, archived from the original on 10 October 2010, retrieved 19 May 2010

- ^ Durbach (2009), p. 34

- ^ Durbach (2009), pp. 37–38

- ^ Vigor-Mungovin, Joanne (2016). Joseph: The Life, Times and Places of the Elephant Man. Ernakulam, Kerala, India: Mango Books. ASIN B01M7YFPSK.

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 171

- ^ a b c Montagu (1971), pp. 41–42

- ^ Howell & Ford (1992), p. 178

- ^ Sitton, Jeanette; Stroshane, Mae Siu Wai (2012). Measured by the soul: the life of Joseph Carey Merrick, also known as the Elephant Man. Friends of Joseph Carey Merrick. pp. 8, 9, 192. ISBN 978-1-300-45725-1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Associated Press (1 June 1979), "'Sweeney Todd' is named best", New York Daily News, Mortimer Zuckerman, archived from the original on 21 March 2021, retrieved 2 June 2010

- ^ "David Schofield". Filmbug. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ "The Elephant Man". unfinishedhistories.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Bowie in 'Elephant Man' role", The Gazette, Canwest, 11 June 1980, archived from the original on 21 March 2021, retrieved 2 June 2010

- ^ "'Elephant Man' on ABC Theater", The Telegraph, Telegraph Publishing Company, 28 March 1981, archived from the original on 21 March 2021, retrieved 2 June 2010

- ^ Herbert, Kate (20 August 2017). "Moving performances but uneven impact". The Herald-Sun. Durham, NC: McClatchy. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Interview - Zak Ford-Williams - Taking on the Elephant Man - Able Magazine". ablemagazine.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

I think there's a slight advantage, because I'm so used to being very aware and having to control my body and my mouth. When I have to change my physicality or my voice I have, I feel, a great awareness to begin with.

- ^ Zak, Ford-Williams (2023). "How The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man connects with the disabled experience". www.dailymotion.com. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ Wright, Tom. "The Real & Imagined History of the Elephant Man". Nick Hern Books. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "Charlie Heaton is The Elephant Man". BBC. 22 August 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Anger over casting of Stranger Things star Charlie Heaton as Elephant Mann". Sky News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ O'Grady, Sean (10 June 2019). "Year of the Rabbit review: Matt Berry in superb form as drunken and incompetent copper". The Independent. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ Petitgirard, Laurent. "Laurent Petitgiraud, french composer and conductor: Elephant Man". petitgirard.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Vigor-Mungovin, Joanne (2016), Joseph: The Life, Times and Places of the Elephant Man, London: Mango Books, ISBN 978-1-911273-05-9

- Durbach, Nadja (2009), "Monstrosity, Masculinity, and Medicine: Reexamining 'the Elephant Man'", Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-25768-9

- Graham, Peter W.; Oehlschlaeger, Fritz H. (1992), Articulating the Elephant Man: Joseph Merrick and His Interpreters, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-4357-0

- Howell, Michael; Ford, Peter (1992) [1980], The True History of the Elephant Man (3rd ed.), London: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-016515-9

- Korf, Bruce R. (14 April 2000), Human genetics: a problem-based approach (2nd ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 11–12, ISBN 978-0-632-04425-2

- "The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick" – freak shop pamphlet printed c. 1884 to accompany the exhibition of the Elephant Man; printed in The True History of the Elephant Man, pp. 173–175

- Montagu, Ashley (1971), The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity, New York: E. P. Dutton, ISBN 978-0-87690-037-6

- Sitton, Jeanette; Stroshane, Mae Siu-Wai (2012), Measured By The Soul: The Life of Joseph Carey Merrick, London: The Friends of Joseph Carey Merrick, ISBN 978-1-300-45725-1

- Treves, Frederick (1923), The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, London: Cassell and Co., OCLC 1546705

Further reading

[edit]- Vigor-Mungovin, Joanne (2016), Joseph: The Life, Times and Places of the Elephant Man, London: Mango Books, ISBN 978-1911273059

- Drimmer, Frederick (1985). The Elephant Man. New York: Putnam. ISBN 0-399-21262-0.

- Sherman, Kenneth (1983). Words for Elephant Man. Oakville, Ont., Canada: Mosaic Press. ISBN 0-88962-199-3. OCLC 559821779.

- Sitton, Jeanette; Stroshane, Mae Siu-Wai (2012). Measured by the Soul: The Life of Joseph Carey Merrick. England: Friends of Joseph Carey Merrick Publishing. ISBN 978-1-300-45725-1. OCLC 904080411.

External links

[edit]- Transcripts of the letters written to The Times newspaper by Francis Carr-Gomm, regarding Joseph Merrick.

- Contemporary visual art reference in the work of Australian art Cameron Hayes.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch