User talk:Stephen2000

United States Senate | |

|---|---|

| 113th United States Congress | |

| |

Flag of the U.S. Senate | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

Term limits | None |

| History | |

New session started | January 3, 2013 |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| |

Political groups |

|

Length of term | 6 years |

| Elections | |

| First-past-the-post | |

Last election | November 6, 2012 |

Next election | November 4, 2014 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Senate Chamber United States Capitol Washington, D.C. United States | |

| Website | |

| www | |

The United States Senate is a legislative chamber in the bicameral legislature of the United States of America, and together with the U.S. House of Representatives makes up the U.S. Congress. First convened in 1789, the composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution.[1] Each U.S. state is represented by two senators, regardless of population, who serve staggered six-year terms. The chamber of the United States Senate is located in the north wing of the Capitol, in Washington, D.C., the national capital. The House of Representatives convenes in the south wing of the same building.

The Senate has several exclusive powers not granted to the House, including consenting to treaties as a precondition to their ratification and consenting to or confirming appointments of Cabinet secretaries, federal judges, other federal executive officials, military officers, regulatory officials, ambassadors, and other federal uniformed officers,[2][3] as well as trial of federal officials impeached by the House. The Senate is both a more deliberative[4] and more prestigious[5][6][7] body than the House of Representatives, due to its longer terms, smaller size, and statewide constituencies, which historically led to a more collegial and less partisan atmosphere.[8]

History

[edit]The framers of the Constitution created a bicameral Congress primarily as a compromise between those who felt that each state, since it was sovereign, should be equally represented, and those who felt the legislature must directly represent the people, as the House of Commons did in Britain. There was also a desire to have two Houses that could act as an internal check on each other. One was intended to be a "People's House" directly elected by the people, and with short terms obliging the representatives to remain close to their constituents. The other was intended to represent the states to such extent as they retained their sovereignty except for the powers expressly delegated to the national government. The Senate was thus not intended to represent the people of the United States equally. The Constitution provides that the approval of both chambers is necessary for the passage of legislation.[9]

The Senate of the United States was formed on the example of the ancient Roman Senate. The name is derived from the senatus, Latin for council of elders (from senex meaning old man in Latin).[10]

James Madison made the following comment about the Senate:

- In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of landed proprietors would be insecure. An agrarian law would soon take place. If these observations be just, our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation. Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests, and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority. The senate, therefore, ought to be this body; and to answer these purposes, they ought to have permanency and stability.[11]

The Constitution stipulates that no constitutional amendment may be created to deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without that state's consent. The District of Columbia and all other territories are not entitled to representation in either House of the Congress. The District of Columbia elects two shadow senators, but they are officials of the D.C. city government and not members of the U.S. Senate.[12] The United States has had 50 states since 1959,[13] thus the Senate has had 100 senators since 1959.[14]

The disparity between the most and least populous states has grown since the Connecticut Compromise, which granted each state two members of the Senate and at least one member of the House of Representatives, for a total minimum of three presidential Electors, regardless of population. In 1787, Virginia had roughly 10 times the population of Rhode Island, whereas today California has roughly 70 times the population of Wyoming, based on the 1790 and 2000 censuses. This means some citizens are effectively two orders of magnitude better represented in the Senate than those in other states. Seats in the House of Representatives are approximately proportionate to the population of each state, reducing the disparity of representation.

Before the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913, senators were elected by the individual state legislatures.[16] However, problems with repeated vacant seats due to the inability of a legislature to elect senators, intrastate political struggles, and even bribery and intimidation gradually led to a growing movement to amend the Constitution to allow for the direct election of senators.[17]

Membership

[edit]Qualifications

[edit]| This article is part of a series on the |

| United States Senate |

|---|

|

| History of the United States Senate |

| Members |

| |

| Politics and procedure |

| Places |

Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution sets three qualifications for senators: 1) they must be at least 30 years old, 2) they must have been citizens of the United States for at least the past nine years, and 3) they must be inhabitants of the states they seek to represent at the time of their election. The age and citizenship qualifications for senators are more stringent than those for representatives. In Federalist No. 62, James Madison justified this arrangement by arguing that the "senatorial trust" called for a "greater extent of information and stability of character."

The Senate (not the judiciary) is the sole judge of a senator's qualifications. During its early years, however, the Senate did not closely scrutinize the qualifications of its members. As a result, three senators who failed to meet the age qualification were nevertheless admitted to the Senate: Henry Clay (aged 29 in 1806), Armistead Thomson Mason (aged 28 in 1816), and John Eaton (aged 28 in 1818). Such an occurrence, however, has not been repeated since.[18] In 1934, Rush D. Holt, Sr. was elected to the Senate at the age of 29; he waited until he turned 30 (on the following June 19) to take the oath of office. In November 1972, Joe Biden was elected to the Senate at the age of 29, but he reached his 30th birthday before the swearing-in ceremony for incoming senators in January 1973.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution disqualifies from the Senate any federal or state officers who had taken the requisite oath to support the Constitution, but later engaged in rebellion or aided the enemies of the United States. This provision, which came into force soon after the end of the Civil War, was intended to prevent those who had sided with the Confederacy from serving. That Amendment, however, also provides a method to remove that disqualification: a two-thirds vote of both chambers of Congress.

Elections and term

[edit]Originally, senators were selected by the state legislatures, not by popular elections. By the early years of the 20th century, the legislatures of as many as 29 states had provided for popular election of senators by referendums.[19] Popular election to the Senate was standardized nationally in 1913 by the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment.

Term

[edit]Senators serve terms of six years each; the terms are staggered so that approximately one-third of the seats are up for election every two years. This was achieved by dividing the senators of the 1st Congress into thirds (called classes), where the terms of one-third expired after two years, the terms of another third expired after four, and the terms of the last third expired after six years. This arrangement was also followed after the admission of new states into the union. The staggering of terms has been arranged such that both seats from a given state are not contested in the same general election, except when a mid-term vacancy is being filled. Current senators whose six-year terms expire on January 3, 2015, belong to Class II.

The Constitution set the date for Congress to convene—Article 1, Section 4, Clause 2 originally set that date for the third day of December. The Twentieth Amendment, however, changed the opening date for sessions to noon on the third day of January, unless they shall by law appoint a different day. The Twentieth Amendment also states that Congress shall assemble at least once in every year and allows Congress to determine its convening and adjournment dates and other dates and schedules as it desires. Article 1, Section 3 provides that the President has the power to convene Congress on extraordinary occasions at his discretion.

A member who has been elected, but not yet seated, is called a "senator-elect"; a member who has been appointed to a seat, but not yet seated, is called a "senator-designate".

Elections

[edit]Elections to the Senate are held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November in even-numbered years, Election Day, and coincide with elections for the House of Representatives.[20] Senators are elected by their state as a whole. In most states (since 1970), a primary election is held first for the Republican and Democratic parties, with the general election following a few months later. Ballot access rules for independent and minor party candidates vary from state to state. The winner is the candidate who receives a plurality of the popular vote. In some states, runoffs are held if no candidate wins a majority.

Mid-term vacancies

[edit]The Seventeenth Amendment requires mid-term vacancies in the Senate to be filled by special election. If a special election for one seat happens to coincide with a general election for the state's other seat, each seat is contested separately. A senator elected in a special election takes office as soon as possible after the election and serves until the original six-year term expires (i.e. not for a full term).

The Seventeenth Amendment also allows state legislatures to give their governors the power to appoint temporary senators until the special election takes place. The official wording provides that "the legislature of any State may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct."

As of 2009, forty-six states permit their governors to make such appointments. In thirty-seven of these states, the special election to permanently fill the U.S. Senate seat is customarily held at the next biennial congressional election. The other nine states require that special elections be held outside of the normal two-year election cycle in some or all circumstances. In four states (Arizona, Hawaii, Utah, and Wyoming), the governor must appoint someone of the same political party as the previous incumbent.

Oregon and Wisconsin require special elections for vacancies with no interim appointment, and Oklahoma permits the governor to appoint only the winner of a special election.[21] In September 2009, Massachusetts changed its law to enable the governor to appoint a temporary replacement for the late Senator Kennedy until the special election in January 2010.[22][23] In 2004, Alaska enacted legislation and a separate ballot referendum that took effect on the same day, but that conflicted with each other. The effect of the ballot-approved law is to withhold from the governor authority to appoint a senator.[24] Because the 17th Amendment vests the power to grant that authority to the legislature – not the people or the state generally – it is unclear whether the ballot measure supplants the legislature's statute granting that authority.[24] As a result, it is uncertain whether an Alaska governor may appoint an interim senator to serve until a special election is held to fill the vacancy.

The temporary appointee may run in the special election in his or her own right.

Oath

[edit]| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

The Constitution requires that senators take an oath or affirmation to support the Constitution.[25] Congress has prescribed the following oath for new senators:

I, ___ ___, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.[26]

Salary and benefits

[edit]The annual salary of each senator, as of 2013, is $174,000;[27] the president pro tempore and party leaders receive $193,400.[27][28] In June 2003, at least 40 of the then-senators were millionaires.[29]

Along with earning salaries, senators receive retirement and health benefits that are identical to other federal employees, and are fully vested after five years of service.[28] Senators are covered by the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) or Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS). As it is for federal employees, congressional retirement is funded through taxes and the participants' contributions. Under FERS, senators contribute 1.3% of their salary into the FERS retirement plan and pay 6.2% of their salary in Social Security taxes. The amount of a senator's pension depends on the years of service and the average of the highest 3 years of their salary. The starting amount of a senator's retirement annuity may not exceed 80% of their final salary. In 2006, the average annual pension for retired senators and representatives under CSRS was $60,972, while those who retired under FERS, or in combination with CSRS, was $35,952.[28]

Political prominence

[edit]Senators are regarded as more prominent political figures than members of the House of Representatives because there are fewer of them, and because they serve for longer terms, usually represent larger constituencies (the exception being House at-large districts, which similarly comprise entire states), sit on more committees, and have more staffers. Far more senators have been nominees for the presidency than representatives. Furthermore, three senators (Warren Harding, John F. Kennedy, and Barack Obama) have been elected president while serving in the Senate, while only one Representative (James Garfield) has been elected president while serving in the House, though Garfield was also a Senator-elect at the time of his election to the Presidency, having been chosen by the Ohio Legislature to fill a Senate vacancy.

Seniority

[edit]According to the convention of Senate seniority, the senator with the longer tenure in each state is known as the "senior senator"; the other is the "junior senator". This convention does not have official significance, though it is a factor in the selection of physical offices.[30] In the 113th Congress, the most-senior "junior senator" is Tom Harkin of Iowa, who was sworn in on January 3, 1985 and is currently 7th in seniority, behind Chuck Grassley who was sworn in on January 3, 1981 and is currently 6th in seniority. With the resignation of John Kerry, the most-junior "senior senator" is Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who was sworn in January 3, 2013, and is currently 95th in seniority, ahead of senator Ed Markey who was sworn in July 16, 2013 and is currently 98th in seniority.

Expulsion and other disciplinary actions

[edit]The Senate may expel a senator by a two-thirds vote. Fifteen senators have been expelled in the history of the Senate: William Blount, for treason, in 1797, and fourteen in 1861 and 1862 for supporting the Confederate secession. Although no senator has been expelled since 1862, many senators have chosen to resign when faced with expulsion proceedings – for example, Bob Packwood in 1995. The Senate has also censured and condemned senators; censure requires only a simple majority and does not remove a senator from office. Some senators have opted to withdraw from their re-election races rather than face certain censure or expulsion, such as Robert Torricelli in 2002.

Majority and minority parties

[edit]The "Majority party" is the political party that either has a majority of seats or can form a coalition or caucus with a majority of seats; if two or more parties are tied, the vice president's affiliation determines which party is the majority party. The next-largest party is known as the minority party. The president pro tempore, committee chairs, and some other officials are generally from the majority party; they have counterparts (for instance, the "ranking members" of committees) in the minority party. Independents and members of third parties (so long as they do not caucus with or support either of the larger parties) are not considered in determining which is the majority party.

Seating

[edit]The Democratic Party traditionally sits to the presiding officer's right, and the Republican Party traditionally sits to the presiding officer's left, regardless which party has a majority of seats.[31] In this respect, the Senate differs from the House of Commons of the United Kingdom and other parliamentary bodies in the Commonwealth of Nations and elsewhere.

Officers

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

The Vice President of the United States presides over the Senate,[1] but the party leaders have the real power and they control procedure. Many non-member officers are also hired to run the day-to-day functions of the Senate.

Presiding over the Senate

[edit]The Vice President of the United States is the ex officio President of the Senate, with authority to preside over the Senate's sessions, although he can vote only to break a tie.[1] For decades the task of presiding over Senate sessions was one of the vice president's principal duties. Since the 1950s, vice presidents have presided over few Senate debates. Instead, they have usually presided only on ceremonial occasions, such as joint sessions, or at times when a tie vote on an important issue is anticipated. The Constitution authorizes the Senate to elect a president pro tempore (Latin for "president for a time") to preside in the vice president's absence; the most senior senator of the majority party is customarily chosen to serve in this position.[1] Like the vice president, the president pro tempore does not normally preside over the Senate, but typically delegates the responsibility of presiding to junior senators of the majority party, usually in blocks of one hour on a rotating basis. Frequently, freshmen senators (newly elected members) are asked to preside so that they may become accustomed to the rules and procedures of the body.

The presiding officer sits in a chair in the front of the Senate chamber. The powers of the presiding officer of the Senate are far less extensive than those of the Speaker of the House. The presiding officer calls on senators to speak (by the rules of the Senate, the first senator who rises is recognized); ruling on points of order (objections by senators that a rule has been breached, subject to appeal to the whole chamber); and announcing the results of votes.

Party leaders

[edit]Each party elects Senate party leaders. Floor leaders act as the party chief spokespeople. The Senate Majority Leader is responsible for controlling the agenda of the chamber by scheduling debates and votes. Each party elects an assistant leader (whip) who works to ensure that their party's senators vote as the party leadership desires.

Non-member officers

[edit]The Senate is served by several officials who are not members. The Senate's chief administrative officer is the Secretary of the Senate, who maintains public records, disburses salaries, monitors the acquisition of stationery and supplies, and oversees clerks. The Assistant Secretary of the Senate aids the secretary in his or her work. Another official is the Sergeant at Arms who, as the Senate's chief law enforcement officer, maintains order and security on the Senate premises. The Capitol Police handle routine police work, with the sergeant at arms primarily responsible for general oversight. Other employees include the Chaplain, who is elected by the Senate, and Pages, who are appointed.

Procedure

[edit]Daily sessions

[edit]

The Senate uses Standing Rules of the Senate for operation. Like the House of Representatives, the Senate meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. At one end of the chamber of the Senate is a dais from which the presiding officer presides. The lower tier of the dais is used by clerks and other officials. One hundred desks are arranged in the chamber in a semicircular pattern and are divided by a wide central aisle. By tradition, Republicans sit to the right of the center aisle and Democrats to the left, facing the presiding officer.[32] Each senator chooses a desk based on seniority within the party. By custom, the leader of each party sits in the front row along the center aisle. Sessions of the Senate are opened with a special prayer or invocation and typically convene on weekdays. Sessions of the Senate are generally open to the public and are broadcast live on television, usually by C-SPAN 2.

Senate procedure depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs and traditions. The Senate commonly waives some of its stricter rules by unanimous consent. Unanimous consent agreements are typically negotiated beforehand by party leaders. A senator may block such an agreement, but in practice, objections are rare. The presiding officer enforces the rules of the Senate, and may warn members who deviate from them. The presiding officer sometimes uses the gavel of the Senate to maintain order.

A "hold" is placed when the leader's office is notified that a senator intends to object to a request for unanimous consent from the Senate to consider or pass a measure. A hold may be placed for any reason and can be lifted by a senator at any time. A senator may place a hold simply to review a bill, to negotiate changes to the bill, or to kill the bill. A bill can be held for as long as the senator who objects to the bill wishes to block its consideration.

Holds can be overcome, but require time-consuming procedures such as filing cloture. Holds are considered private communications between a senator and the Leader, and are sometimes referred to as "secret holds". A senator may disclose that he or she has placed a hold.

The Constitution provides that a majority of the Senate constitutes a quorum to do business. Under the rules and customs of the Senate, a quorum is always assumed present unless a quorum call explicitly demonstrates otherwise. A senator may request a quorum call by "suggesting the absence of a quorum"; a clerk then calls the roll of the Senate and notes which members are present. In practice, senators rarely request quorum calls to establish the presence of a quorum. Instead, quorum calls are generally used to temporarily delay proceedings; usually such delays are used while waiting for a senator to reach the floor to speak or to give leaders time to negotiate. Once the need for a delay has ended, a senator may request unanimous consent to rescind the quorum call.

Debate

[edit]Debate, like most other matters governing the internal functioning of the Senate, is governed by internal rules adopted by the Senate. During debate, senators may only speak if called upon by the presiding officer, but the presiding officer is required to recognize the first senator who rises to speak. Thus, the presiding officer has little control over the course of debate. Customarily, the Majority Leader and Minority Leader are accorded priority during debates even if another senator rises first. All speeches must be addressed to the presiding officer, who is addressed as "Mr. President" or "Madam President", and not to another member; other Members must be referred to in the third person. In most cases, senators do not refer to each other by name, but by state or position, using forms such as "the senior senator from Virginia", "the gentlewoman from California", or "my distinguished friend the Chairman of the Judiciary Committee". Senators address the Senate standing next to their desk.[33]

Apart from rules governing civility, there are few restrictions on the content of speeches; there is no requirement that speeches be germane to the matter before the Senate.

The rules of the Senate provide that no senator may make more than two speeches on a motion or bill on the same legislative day. A legislative day begins when the Senate convenes and ends with adjournment; hence, it does not necessarily coincide with the calendar day. The length of these speeches is not limited by the rules; thus, in most cases, senators may speak for as long as they please. Often, the Senate adopts unanimous consent agreements imposing time limits. In other cases (for example, for the budget process), limits are imposed by statute. However, the right to unlimited debate is generally preserved.

Filibuster and cloture

[edit]The filibuster is a tactic used to defeat bills and motions by prolonging debate indefinitely. A filibuster may entail long speeches, dilatory motions, and an extensive series of proposed amendments. The Senate may end a filibuster by invoking cloture. In most cases, cloture requires the support of three-fifths of the Senate; however, if the matter before the Senate involves changing the rules of the body – this includes amending provisions regarding the filibuster – a two-thirds majority is required. In current practice, the threat of filibuster is more important than its use; almost any motion that does not have the support of three-fifths of the Senate effectively fails. This means that 41 senators, which could represent as little as 12.3% of the U.S. population, can make a filibuster happen. Historically, cloture has rarely been invoked because bipartisan support is usually necessary to obtain the required supermajority, so a bill that already has bipartisan support is rarely subject to threats of filibuster. However, motions for cloture have increased significantly in recent years.

If the Senate invokes cloture, debate does not end immediately; instead, it is limited to 2 additional hours unless increased by another three-fifths vote. The longest filibuster speech in the history of the Senate was delivered by Strom Thurmond, who spoke for over 24 hours in an unsuccessful attempt to block the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957.[34]

Under certain circumstances, the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 provides for a process called "reconciliation" by which Congress can pass bills related to the budget without those bills being subject to a filibuster. This is accomplished by limiting all Senate floor debate to 20 hours.[35]

Voting

[edit]When debate concludes, the motion in question is put to a vote. The Senate often votes by voice vote. The presiding officer puts the question, and Members respond either "Yea" (in favor of the motion) or "Nay" (against the motion). The presiding officer then announces the result of the voice vote. A senator, however, may challenge the presiding officer's assessment and request a recorded vote. The request may be granted only if it is seconded by one-fifth of the senators present. In practice, however, senators second requests for recorded votes as a matter of courtesy. When a recorded vote is held, the clerk calls the roll of the Senate in alphabetical order; senators respond when their name is called. Senators who were not in the chamber when their name was called may still cast a vote so long as the voting remains open. The vote is closed at the discretion of the presiding officer, but must remain open for a minimum of 15 minutes. If the vote is tied, the vice president, if present, is entitled to cast a tie-breaking vote. If the vice president is not present, the motion fails.[36]

Bills which are filibustered require a three fifth majority to overcome the cloture vote (which usually means 60 votes) and get to the normal vote where a simple majority (usually 51 votes) will approve the bill. This has caused some news media to confuse the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster with the 51 votes needed to approve a bill, with for example USA Today erroneously stating "The vote was 58-39 in favor of the provision establishing concealed carry permit reciprocity in the 48 states that have concealed weapons laws. That fell two votes short of the 60 needed to approve the measure".[37]

Closed session

[edit]On occasion, the Senate may go into what is called a secret or closed session. During a closed session, the chamber doors are closed, cameras are turned off, and the galleries are completely cleared of anyone not sworn to secrecy, not instructed in the rules of the closed session, or not essential to the session. Closed sessions are rare and usually held only when the Senate is discussing sensitive subject matter such as information critical to national security, private communications from the president, or deliberations during impeachment trials. A senator may call for and force a closed session if the motion is seconded by at least one other member, but an agreement usually occurs beforehand.[38] If the Senate does not approve release of a secret transcript, the transcript is stored in the Office of Senate Security and ultimately sent to the national archives. The proceedings remain sealed indefinitely until the Senate votes to remove the injunction of secrecy.[39]

Calendars

[edit]The Senate maintains a Senate Calendar and an Executive Calendar.[40] The former identifies bills and resolutions awaiting Senate floor actions. The latter identifies executive resolutions, treaties, and nominations reported out by Senate committee(s) and awaiting Senate floor action. Both are updated each day the Senate is in session.

Committees

[edit]

The Senate uses committees (and their subcommittees) for a variety of purposes, including the review of bills and the oversight of the executive branch. Formally, the whole Senate appoints committee members. In practice, however, the choice of members is made by the political parties. Generally, each party honors the preferences of individual senators, giving priority based on seniority. Each party is allocated seats on committees in proportion to its overall strength.

Most committee work is performed by 16 standing committees, each of which has jurisdiction over a field such as finance or foreign relations. Each standing committee may consider, amend, and report bills that fall under its jurisdiction. Furthermore, each standing committee considers presidential nominations to offices related to its jurisdiction. (For instance, the Judiciary Committee considers nominees for judgeships, and the Foreign Relations Committee considers nominees for positions in the Department of State.) Committees may block nominees and impede bills from reaching the floor of the Senate. Standing committees also oversee the departments and agencies of the executive branch. In discharging their duties, standing committees have the power to hold hearings and to subpoena witnesses and evidence.

The Senate also has several committees that are not considered standing committees. Such bodies are generally known as select or special committees; examples include the Select Committee on Ethics and the Special Committee on Aging. Legislation is referred to some of these committees, although the bulk of legislative work is performed by the standing committees. Committees may be established on an ad hoc basis for specific purposes; for instance, the Senate Watergate Committee was a special committee created to investigate the Watergate scandal. Such temporary committees cease to exist after fulfilling their tasks.

The Congress includes joint committees, which include members from both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Some joint committees oversee independent government bodies; for instance, the Joint Committee on the Library oversees the Library of Congress. Other joint committees serve to make advisory reports; for example, there exists a Joint Committee on Taxation. Bills and nominees are not referred to joint committees. Hence, the power of joint committees is considerably lower than those of standing committees.

Each Senate committee and subcommittee is led by a chair (usually a member of the majority party). Formerly, committee chairs were determined purely by seniority; as a result, several elderly senators continued to serve as chair despite severe physical infirmity or even senility.[41] Committee chairs are elected, but, in practice, seniority is rarely bypassed. The chairs hold extensive powers: they control the committee's agenda, and so decide how much, if any, time to devote to the consideration of a bill; they act with the power of the committee in disapproving or delaying a bill or a nomination by the president; they manage on the floor of the full Senate the consideration of those bills the committee reports. This last role was particularly important in mid-century, when floor amendments were thought not to be collegial. They also have considerable influence: senators who cooperate with their committee chairs are likely to accomplish more good for their states than those who do not. The Senate rules and customs were reformed in the twentieth century, largely in the 1970s. Committee chairmen have less power and are generally more moderate and collegial in exercising it, than they were before reform.[42] The second-highest member, the spokesperson on the committee for the minority party, is known in most cases as the ranking member.[43] In the Select Committee on Intelligence and the Select Committee on Ethics, however, the senior minority member is known as the vice chair.

Recent criticisms of the Senate's operations object to what the critics argue is obsolescence as a result of partisan paralysis and a preponderance of arcane rules.[44][45]

Functions

[edit]Legislation

[edit]Bills may be introduced in either chamber of Congress. However, the Constitution's Origination Clause provides that "All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives".[46] As a result, the Senate does not have the power to initiate bills imposing taxes. Furthermore, the House of Representatives holds that the Senate does not have the power to originate appropriation bills, or bills authorizing the expenditure of federal funds.[47][48][49] Historically, the Senate has disputed the interpretation advocated by the House. However, when the Senate originates an appropriations bill, the House simply refuses to consider it, thereby settling the dispute in practice.[citation needed] The constitutional provision barring the Senate from introducing revenue bills is based on the practice of the British Parliament, in which only the House of Commons may originate such measures.[50]

Although the Constitution gave the House the power to initiate revenue bills, in practice the Senate is equal to the House in the respect of spending. As Woodrow Wilson wrote:[51]

| “ | The Senate's right to amend general appropriation bills has been allowed the widest possible scope. The upper house may add to them what it pleases; may go altogether outside of their original provisions and tack to them entirely new features of legislation, altering not only the amounts but even the objects of expenditure, and making out of the materials sent them by the popular chamber measures of an almost totally new character. | ” |

The approval of both houses is required for any bill, including a revenue bill, to become law. Both Houses must pass the same version of the bill; if there are differences, they may be resolved by sending amendments back and forth or by a conference committee, which includes members of both bodies.

Checks and balances

[edit]The Constitution provides several unique functions for the Senate that form its ability to "check and balance" the powers of other elements of the Federal Government. These include the requirement that the Senate may advise and must consent to some of the president's government appointments; also the Senate must consent to all treaties with foreign governments; it tries all impeachments, and it elects the vice president in the event no person gets a majority of the electoral votes.

The president can make certain appointments only with the advice and consent of the Senate. Officials whose appointments require the Senate's approval include members of the Cabinet, heads of most federal executive agencies, ambassadors, Justices of the Supreme Court, and other federal judges. Under Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, a large number of government appointments are subject to potential confirmation; however, Congress has passed legislation to authorize the appointment of many officials without the Senate's consent (usually, confirmation requirements are reserved for those officials with the most significant final decision-making authority). Typically, a nominee is first subject to a hearing before a Senate committee. Thereafter, the nomination is considered by the full Senate. The majority of nominees are confirmed, but in a small number of cases each year, Senate Committees will purposely fail to act on a nomination to block it. In addition, the president sometimes withdraws nominations when they appear unlikely to be confirmed. Because of this, outright rejections of nominees on the Senate floor are infrequent (there have been only nine Cabinet nominees rejected outright in the history of the United States).[citation needed]

The powers of the Senate concerning nominations are, however, subject to some constraints. For instance, the Constitution provides that the president may make an appointment during a congressional recess without the Senate's advice and consent. The recess appointment remains valid only temporarily; the office becomes vacant again at the end of the next congressional session. Nevertheless, presidents have frequently used recess appointments to circumvent the possibility that the Senate may reject the nominee. Furthermore, as the Supreme Court held in Myers v. United States, although the Senate's advice and consent is required for the appointment of certain executive branch officials, it is not necessary for their removal.[52]

The Senate also has a role in ratifying treaties. The Constitution provides that the president may only "make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur." However, not all international agreements are considered treaties under US domestic law, even if they are considered treaties under international law. Congress has passed laws authorizing the president to conclude executive agreements without action by the Senate. Similarly, the president may make congressional-executive agreements with the approval of a simple majority in each House of Congress, rather than a two-thirds majority in the Senate. Neither executive agreements nor congressional-executive agreements are mentioned in the Constitution, leading some scholars such as Laurence Tribe and John Yoo[53] to suggest that they unconstitutionally circumvent the treaty-ratification process. However, courts have upheld the validity of such agreements.[54]

The Constitution empowers the House of Representatives to impeach federal officials for "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors" and empowers the Senate to try such impeachments. If the sitting President of the United States is being tried, the Chief Justice of the United States presides over the trial. During an impeachment trial, senators are constitutionally required to sit on oath or affirmation. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority of the senators present. A convicted official is automatically removed from office; in addition, the Senate may stipulate that the defendant be banned from holding office. No further punishment is permitted during the impeachment proceedings; however, the party may face criminal penalties in a normal court of law.

In the history of the United States, the House of Representatives has impeached sixteen officials, of whom seven were convicted. (One resigned before the Senate could complete the trial.)[55] Only two presidents of the United States have ever been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998. Both trials ended in acquittal; in Johnson's case, the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction.

Under the Twelfth Amendment, the Senate has the power to elect the vice president if no vice presidential candidate receives a majority of votes in the Electoral College. The Twelfth Amendment requires the Senate to choose from the two candidates with the highest numbers of electoral votes. Electoral College deadlocks are rare. In the history of the United States, the Senate has only broken a deadlock once. In 1837, it elected Richard Mentor Johnson. The House elects the president if the Electoral College deadlocks on that choice.

Current composition and election results

[edit]

Current party standings

[edit]The party composition of the Senate during the 113th Congress (since the October 31, 2013 swearing-in of Democratic Sen. Cory Booker):

| |||||||||||||||

113th Congress

[edit]The 113th United States Congress will run from January 3, 2013 to January 3, 2015.

See also

[edit]- Bibliography of U.S. congressional memoirs (U.S. senators)

- Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate

- List of African-American United States Senators

- List of current United States Senators by age

- United States presidents and control of congress

- Women in the United States Senate

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Constitution of the United States". Senate.gov. March 26, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ "Constitution of the United States". Senate.gov. March 26, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ Senate Confirmation Process: A Brief Overview

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Richard L. Berke (September 12, 1999). "In Fight for Control of Congress, Tough Skirmishes Within Parties". The New York Times.

- ^ Joseph S. Friedman (March 30, 2009). "The Rapid Sequence of Events Forcing the Senate's Hand: A Reappraisal of the Seventeenth Amendment, 1890–1913". University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ "Agreeing to Disagree: Agenda Content and Senate Partisanship, 198". Ingentaconnect.com. June 16, 2006. doi:10.3162/036298008784311000. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Constitution: article 1, Section 1".

- ^ "Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary: senate". Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ See Notes of the Secret Debates of the Federal Convention of 1787 by Robert Yates

- ^ "Non-voting members of Congress". Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "Hawaii becomes 50th state". Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Constitution: article 1, Section 1". Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ "Party In Power - Congress and Presidency - A Visual Guide To The Balance of Power In Congress, 1945-2008". Uspolitics.about.com. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Article I, Section 3: "The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two senators from each state, chosen by the legislature thereof, for six years; and each senator shall have one vote."

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Art & History Home > Origins & Development > Institutional Development > Direct Election of Senators". Senate.gov. March 26, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ 1801–1850, November 16, 1818: Youngest Senator. United States Senate. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ "Direct Election of Senators". U.S. Senate official website.

- ^ 2 U.S.C. § 1

- ^ Neale, Thomas H. (March 10, 2009). "Filling U.S. Senate Vacancies: Perspectives and Contemporary Developments" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 8.

- ^ DeLeo, Robert A. (September 17, 2009). "Temporary Appointment of US Senator". Massachusetts Great and General Court.

- ^ DeLeo, Robert A. (September 17, 2009). "Temporary Appointment of US Senator Shall not be a candidate in special election" (PDF). Massachusetts Great and General Court.

- ^ a b "Stevens could keep seat in Senate". Anchorage Daily News. October 28, 2009.

- ^ United States Constitution, Article VI

- ^ See: 5 U.S.C. § 3331; see also: U.S. Senate Oath of Office

- ^ a b Salaries. United States Senate. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c "US Congress Salaries and Benefits". Usgovinfo.about.com. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Sean Loughlin and Robert Yoon (June 13, 2003). "Millionaires populate U.S. Senate". CNN. Retrieved June 19, 2006.

- ^ Baker, Richard A. "Traditions of the United States Senate" (PDF). Page 4.

- ^ "Seating Arrangement". Senate Chamber Desks. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ CRS Report for Congress, "Guide to Individuals Seated on the Senate Dais" (updated May 6, 2008). Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ Martin B. Gold, Senate Procedure and Practice, p.39: Every member, when he speaks, shall address the chair, standing in his place, and when he has finished, shall sit down.

- ^ Quinton, Jeff. "Thurmond's Filibuster". Backcountry Conservative. July 27, 2003. Retrieved June 19, 2006.

- ^ Reconciliation, (Procedure in the Senate).

- ^ "Yea or Nay? Voting in the Senate". Senate.gov. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "How majority rule works in the U.S. Senate". Nieman Watchdog. July 31, 2009.

- ^ http://www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/RS20145.pdf

- ^ http://www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/98-718.pdf

- ^ "Calendars & Schedules" via Senate.gov

- ^ See, for examples, American Dictionary of National Biography on John Sherman and Carter Glass; in general, Ritchie, Congress, p. 209

- ^ Ritchie, Congress, p. 44. Zelizer, On Capitol Hill describes this process; one of the reforms is that seniority within the majority party can now be bypassed, so that chairs do run the risk of being deposed by their colleagues. See in particular p. 17, for the unreformed Congress, and pp.188–9, for the Stevenson reforms of 1977.

- ^ Ritchie, Congress, pp .44, 175, 209

- ^ Mark Murray (August 2, 2010). "The inefficient Senate". Firstread.msnbc.msn.com. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ Packer, George (January 7, 2009). "Filibusters and arcane obstructions in the Senate". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ "Constitution of the United States". Senate.gov. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Saturno, James. "The Origination Clause of the U.S. Constitution: Interpretation and Enforcement", CRS Report for Congress (Mar-15-2011).

- ^ Wirls, Daniel and Wirls, Stephen. The Invention of the United States Senate, p. 188 (Taylor & Francis 2004).

- ^ Woodrow Wilson wrote that the Senate has extremely broad amendment authority with regard to appropriations bills, as distinguished from bills that levy taxes. See Wilson, Woodrow. Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics, pp. 155-156 (Transaction Publishers 2002). According to the Library of Congress, the Constitution provides the origination requirement for revenue bills, whereas tradition provides the origination requirement for appropriation bills. See Sullivan, John. "How Our Laws Are Made", Library of Congress (accessed August 26, 2013).

- ^ Sargent, Noel. "Bills for Raising Revenue Under the Federal and State Constitutions", Minnesota Law Review, Vol. 4, p. 330 (1919).

- ^ Wilson Congressional Government, Chapter III: "Revenue and Supply". Text common to all printings or "editions"; in Papers of Woodrow Wilson it is Vol.4 (1968), p.91; for unchanged text, see p. 13, ibid.

- ^ Recess Appointments FAQ (PDF). US Senate, Congressional Research Service. Retrieved November 20, 2007; Ritchie, Congress p. 178.

- ^ Bolton, John R. (January 5, 2009). "Restore the Senate's Treaty Power". The New York Times.

- ^ For an example, and a discussion of the literature, see Laurence Tribe, "Taking Text and Structure Seriously: Reflections on Free-Form Method in Constitutional Interpretation", Harvard Law Review, Vol. 108, No. 6. (Apr. 1995), pp. 1221–1303.

- ^ Complete list of impeachment trials. United States Senate. Retrieved November 20, 2007

- ^ Angus King and Bernie Sanders caucus with the Democrats.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baker, Richard A. The Senate of the United States: A Bicentennial History Krieger, 1988.

- Baker, Richard A., ed., First Among Equals: Outstanding Senate Leaders of the Twentieth Century Congressional Quarterly, 1991.

- Barone, Michael, and Grant Ujifusa, The Almanac of American Politics 1976: The Senators, the Representatives and the Governors: Their Records and Election Results, Their States and Districts (1975); new edition every 2 years

- David W. Brady and Mathew D. McCubbins. Party, Process, and Political Change in Congress: New Perspectives on the History of Congress (2002)

- Caro, Robert A. The Years of Lyndon Johnson. Vol. 3: Master of the Senate. Knopf, 2002.

- Comiskey, Michael. Seeking Justices: The Judging of Supreme Court Nominees U. Press of Kansas, 2004.

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation XII: 2005-2008: Politics and Policy in the 109th and 110th Congresses (2010); massive, highly detailed summary of Congressional activity, as well as major executive and judicial decisions; based on Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report and the annual CQ almanac. The Congress and the Nation 2009-2012 vol XIII has been announced for September 2014 publication.

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 2001–2004 (2005);

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1997–2001 (2002)

- Congressional Quarterly. Congress and the Nation: 1993–1996 (1998)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1989–1992 (1993)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1985–1988 (1989)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1981–1984 (1985)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1977–1980 (1981)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1973–1976 (1977)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1969–1972 (1973)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1965–1968 (1969)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1945–1964 (1965), the first of the series

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr. Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations. Cambridge U. Press, 2001.

- Davidson, Roger H., and Walter J. Oleszek, eds. (1998). Congress and Its Members, 6th ed. Washington DC: Congressional Quarterly. (Legislative procedure, informal practices, and member information)

- Gould, Lewis L. The Most Exclusive Club: A History Of The Modern United States Senate (2005)

- Hernon, Joseph Martin. Profiles in Character: Hubris and Heroism in the U.S. Senate, 1789–1990 Sharpe, 1997.

- Hoebeke, C. H. The Road to Mass Democracy: Original Intent and the Seventeenth Amendment. Transaction Books, 1995. (Popular elections of senators)

- Lee, Frances E. and Oppenheimer, Bruce I. Sizing Up the Senate: The Unequal Consequences of Equal Representation. U. of Chicago Press 1999. 304 pp.

- McFarland, Ernest W. The Ernest W. McFarland Papers: The United States Senate Years, 1940–1952. Prescott, Ariz.: Sharlot Hall Museum, 1995 (Democratic majority leader 1950–52)

- Malsberger, John W. From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938–1952. Susquehanna U. Press 2000

- Mann, Robert. The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell and the Struggle for Civil Rights. Harcourt Brace, 1996

- Ritchie, Donald A. (1991). Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents. Harvard University Press.

- Ritchie, Donald A. (2001). The Congress of the United States: A Student Companion (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Ritchie, Donald A. (2010). The U.S. Congress: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Rothman, David. Politics and Power the United States Senate 1869–1901 (1966)

- Swift, Elaine K. The Making of an American Senate: Reconstitutive Change in Congress, 1787–1841. U. of Michigan Press, 1996

- Valeo, Frank. Mike Mansfield, Majority Leader: A Different Kind of Senate, 1961–1976 Sharpe, 1999 (Senate Democratic leader)

- VanBeek, Stephen D. Post-Passage Politics: Bicameral Resolution in Congress. U. of Pittsburgh Press 1995

- Weller, Cecil Edward, Jr. Joe T. Robinson: Always a Loyal Democrat. U. of Arkansas Press, 1998. (Arkansas Democrat who was Majority leader in 1930s)

- Wilson, Woodrow. Congressional Government. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1885; also 15th ed. 1900, repr. by photoreprint, Transaction books, 2002.

- Wirls, Daniel and Wirls, Stephen. The Invention of the United States Senate Johns Hopkins U. Press, 2004. (Early history)

- Zelizer, Julian E. On Capitol Hill : The Struggle to Reform Congress and its Consequences, 1948–2000 (2006)

- Zelizer, Julian E., ed. The American Congress: The Building of Democracy (2004) (overview)

Official Senate histories

[edit]The following are published by the Senate Historical Office.

- Robert Byrd. The Senate, 1789–1989. Four volumes.

- Vol. I, a chronological series of addresses on the history of the Senate

- Vol. II, a topical series of addresses on various aspects of the Senate's operation and powers

- Vol. III, Classic Speeches, 1830–1993

- Vol. IV, Historical Statistics, 1789–1992

- Dole, Bob. Historical Almanac of the United States Senate

- Hatfield, Mark O., with the Senate Historical Office. Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993 (essays reprinted online)

- Frumin, Alan S. Riddick's Senate Procedure. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1992.

External links

[edit]- The United States Senate Official Website

- List of Senators who died in office, via PoliticalGraveyard.com

- Chart of all U.S. Senate seat-holders, by state, 1978–present, via Texas Tech University

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825, via Tufts University

- Bill Hammons' American Politics Guide – Members of Congress by Committee and State with Partisan Voting Index

virgina senate

[edit]

Stephen2000 | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Colony of Virginia |

| Admitted to the Union | June 25, 1788 (10th) |

| Capital | Richmond |

| Largest city | Virginia Beach |

| Largest county or equivalent | Fairfax County |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Northern Virginia |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Terry McAuliffe (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Ralph Northam (D) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Delegates |

| U.S. senators | Mark Warner (D) Tim Kaine (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 8 Republicans, 3 Democrats (list) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 8,260,405 (2,013 est)[1] |

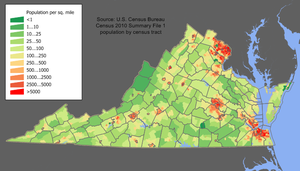

| • Density | 206.7/sq mi (79.8/km2) |

| • Median household income | $61,044 |

| • Income rank | 8th |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | English 94.6%, Spanish 5.4% |

| Latitude | 36° 32′ N to 39° 28′ N |

| Longitude | 75° 15′ W to 83° 41′ W |

Virginia (/vərˈdʒɪnjə/ ), officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state located in the South Atlantic region of the United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" due to its status as a former dominion of the English Crown,[5] and "Mother of Presidents" due to the most U.S. presidents having been born there. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are shaped by the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Chesapeake Bay, which provide habitat for much of its flora and fauna. The capital of the Commonwealth is Richmond; Virginia Beach is the most populous city, and Fairfax County is the most populous political subdivision. The Commonwealth's estimated population as of 2013[update] is over 8.2 million.[1]

The area's history begins with several indigenous groups, including the Powhatan. In 1607 the London Company established the Colony of Virginia as the first permanent New World English colony. Slave labor and the land acquired from displaced Native American tribes each played a significant role in the colony's early politics and plantation economy. Virginia was one of the 13 Colonies in the American Revolution and joined the Confederacy in the American Civil War, during which Richmond was made the Confederate capital and Virginia's northwestern counties seceded to form the state of West Virginia. Although the Commonwealth was under single-party rule for nearly a century following Reconstruction, both major national parties are competitive in modern Virginia.[6]

The Virginia General Assembly is the oldest continuous law-making body in the New World.[7] The state government has been repeatedly ranked most effective by the Pew Center on the States.[8] It is unique in how it treats cities and counties equally, manages local roads, and prohibits its governors from serving consecutive terms. Virginia's economy has many sectors: agriculture in the Shenandoah Valley; federal agencies in Northern Virginia, including the headquarters of the Department of Defense and CIA; and military facilities in Hampton Roads, the site of the region's main seaport. Virginia's economy transitioned from primarily agricultural to industrial during the 1960s and 1970s, and in 2002 computer chips became the state's leading export.[9]

Geography

[edit]Virginia has a total area of 42,774.2 square miles (110,784.7 km2), including 3,180.13 square miles (8,236.5 km2) of water, making it the 35th-largest state by area.[10] Virginia is bordered by Maryland and Washington, D.C. to the north and east; by the Atlantic Ocean to the east; by North Carolina and Tennessee to the south; by Kentucky to the west; and by West Virginia to the north and west. Virginia's boundary with Maryland and Washington, D.C. extends to the low-water mark of the south shore of the Potomac River.[11] The southern border is defined as the 36° 30′ parallel north, though surveyor error led to deviations of as much as three arcminutes.[12] The border with Tennessee was not settled until 1893, when their dispute was brought to the U.S. Supreme Court.[13]

Geology and terrain

[edit]

The Chesapeake Bay separates the contiguous portion of the Commonwealth from the two-county peninsula of Virginia's Eastern Shore. The bay was formed after the drowned river valleys of the Susquehanna River and the James River.[14] Many of Virginia's rivers flow into the Chesapeake Bay, including the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James, which create three peninsulas in the bay.[15][16] Geographically and geologically, Virginia is divided into five regions from east to west: Tidewater, Piedmont, Blue Ridge Mountains, Ridge and Valley, and Cumberland Plateau.[17]

The Tidewater is a coastal plain between the Atlantic coast and the fall line. It includes the Eastern Shore and major estuaries of Chesapeake Bay. The Piedmont is a series of sedimentary and igneous rock-based foothills east of the mountains which were formed in the Mesozoic.[18] The region, known for its heavy clay soil, includes the Southwest Mountains.[19] The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the chain of Appalachian Mountains with the highest points in the state, the tallest being Mount Rogers at 5,729 feet (1,746 m).[20] The Ridge and Valley region is west of the mountains, and includes the Great Appalachian Valley. The region is carbonate rock based, and includes Massanutten Mountain.[21] The Cumberland Plateau and the Cumberland Mountains are in the south-west corner of Virginia, below the Allegheny Plateau. In this region, rivers flow northwest, with a dendritic drainage system, into the Ohio River basin.[22]

The state's carbonate rock is filled with more than 4,000 caves, ten of which are open for tourism.[24] The Virginia seismic zone has not had a history of regular earthquake activity. Earthquakes are rarely above 4.5 in magnitude because Virginia is located away from the edges of the North American Plate. The largest earthquake, at an estimated 5.9 magnitude, was in 1897 near Blacksburg.[25] A 5.8 magnitude earthquake struck central Virginia on August 23, 2011, near Mineral. The earthquake was reportedly felt as far away as Toronto, Canada, Atlanta, Georgia and Florida.[26] Coal mining takes place in the three mountainous regions at 45 distinct coal beds near Mesozoic basins.[27] Over 62 million tons of other non-fuel resources, such as slate, kyanite, sand, or gravel, were also mined in Virginia in 2012.[28]

Climate

[edit]| Virginia state-wide averages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The climate of Virginia becomes increasingly warmer and more humid farther south and east.[29] Seasonal extremes vary from average lows of 26 °F (−3 °C) in January to average highs of 86 °F (30 °C) in July. The Atlantic ocean has a strong effect on eastern and southeastern coastal areas of the state. Influenced by the Gulf Stream, coastal weather is subject to hurricanes, most pronouncedly near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay.[30]

Virginia has an annual average of 35–45 days of thunderstorm activity, particularly in the western part of the state,[31] and an average annual precipitation of 42.7 inches (108 cm).[30] Cold air masses arriving over the mountains in winter can lead to significant snowfalls, such as the Blizzard of 1996 and winter storms of 2009–2010. The interaction of these elements with the state's topography creates distinct microclimates in the Shenandoah Valley, the mountainous southwest, and the coastal plains.[32] Virginia averages seven tornadoes annually, most F2 or lower on the Fujita scale.[33]

In recent years, the expansion of the southern suburbs of Washington, D.C. into Northern Virginia has introduced an urban heat island primarily caused by increased absorption of solar radiation in more densely populated areas.[34] In the American Lung Association's 2011 report, 11 counties received failing grades for air quality, with Fairfax County having the worst in the state, due to automobile pollution.[35][36] Haze in the mountains is caused in part by coal power plants.[37]

Flora and fauna

[edit]Forests cover 65% of the state, primarily with deciduous, broad leaf trees.[38] Lower altitudes are more likely to have small but dense stands of moisture-loving hemlocks and mosses in abundance, with hickory and oak in the Blue Ridge.[29] However since the early 1990s, Gypsy moth infestations have eroded the dominance of oak forests.[39] In the lowland tidewater yellow pines tend to dominate, with bald cypress wetland forests in the Great Dismal and Nottoway swamps. Other common trees and plants include chestnut, maple, tulip poplar, mountain laurel, milkweed, daisies, and many species of ferns. The largest areas of wilderness are along the Atlantic coast and in the western mountains, where the largest populations of trillium wildflowers in North America are found.[29][40] The Atlantic coast regions are host to flora commonly associated with the South Atlantic pine forests and lower Southeast Coastal Plain maritime flora, the latter found primarily in southeastern Virginia.

Mammals include White-tailed deer, black bear, beaver, bobcat, coyote, raccoon, skunk, groundhog, Virginia Opossum, gray fox, red fox, and eastern cottontail rabbit.[41] Other mammals include: nutria, fox squirrel, gray squirrel, flying squirrel, chipmunk, brown bat, and weasel. Birds include cardinals (the State Bird), barred owls, Carolina chickadees, Red-tailed Hawks, Ospreys, Brown Pelicans, Quail, Sea gulls, Bald Eagles, and Wild Turkeys. Virginia is also home to both the large and small pileated woodpecker as well as the common woodpecker. The Peregrine Falcon was reintroduced into Shenandoah National Park in the mid-1990s.[42] Walleye, brook trout, Roanoke bass, and blue catfish are among the 210 known species of freshwater fish.[43] Running brooks with rocky bottoms are often inhabited by plentiful amounts of crayfish and salamanders.[29] The Chesapeake Bay is host to many species, including blue crabs, clams, oysters, and rockfish (also known as striped bass).[44]

Virginia has 30 National Park Service units, such as Great Falls Park and the Appalachian Trail, and one national park, the Shenandoah National Park.[45] Shenandoah was established in 1935 and encompasses the scenic Skyline Drive. Almost 40% of the park's area (79,579 acres/322 km2) has been designated as wilderness under the National Wilderness Preservation System.[46] Additionally, there are 34 Virginia state parks and 17 state forests, run by the Department of Conservation and Recreation and the Department of Forestry.[38][47] The Chesapeake Bay, while not a national park, is protected by both state and federal legislation, and the jointly run Chesapeake Bay Program which conducts restoration on the bay and its watershed. The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge extends into North Carolina, as does the Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, which marks the beginning of the Outer Banks.[48]

History

[edit]

Jamestown 2007 marked Virginia's quadricentennial year, celebrating 400 years since the establishment of the Jamestown Colony. The celebrations highlighted contributions from Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans, each of which had a significant part in shaping Virginia's history.[49][50] Warfare, including among these groups, has also had an important role. Virginia was a focal point in conflicts from the French and Indian War, the American Revolution and the Civil War, to the Cold War and the War on Terrorism.[51] Stories about historic figures, such as those surrounding Pocahontas and John Smith, George Washington's childhood, or the plantation elite in the slave society of the antebellum period, have also created potent myths of state history, and have served as rationales for Virginia's ideology.[52]

Colony

[edit]The first people are estimated to have arrived in Virginia over 12,000 years ago.[53] By 5,000 years ago more permanent settlements emerged, and farming began by 900 AD. By 1500, the Algonquian peoples had founded towns such as Werowocomoco in the Tidewater region, which they referred to as Tsenacommacah. The other major language groups in the area were the Siouan to the west, and the Iroquoians, who included the Nottoway and Meherrin, to the north and south. After 1570, the Algonquians consolidated under Chief Powhatan in response to threats from these other groups on their trade network.[54] Powhatan controlled more than 30 smaller tribes and over 150 settlements, who shared a common Virginia Algonquian language. In 1607, the native Tidewater population was between 13,000 and 14,000.[55]

Several European expeditions, including a group of Spanish Jesuits, explored the Chesapeake Bay during the 16th century.[56] In 1583, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Walter Raleigh a charter to plant a colony north of Spanish Florida.[57] In 1584, Raleigh sent an expedition to the Atlantic coast of North America.[58] The name "Virginia" may have been suggested then by Raleigh or Elizabeth, perhaps noting her status as the "Virgin Queen," and may also be related to a native phrase, "Wingandacoa," or name, "Wingina."[59] Initially the name applied to the entire coastal region from South Carolina to Maine, plus the island of Bermuda.[60] The London Company was incorporated as a joint stock company by the proprietary Charter of 1606, which granted land rights to this area. The Company financed the first permanent English settlement in the "New World", Jamestown. Named for King James I, it was founded in May 1607 by Christopher Newport.[61] In 1619, colonists took greater control with an elected legislature called the House of Burgesses. With the bankruptcy of the London Company in 1624, the settlement was taken into royal authority as an English crown colony.[62]

Life in the colony was perilous, and many died during the Starving Time in 1609 and the Anglo-Powhatan Wars, including the Indian massacre of 1622, which fostered the colonists' negative view of all tribes.[63][64] By 1624, only 3,400 of the 6,000 early settlers had survived.[65] However, European demand for tobacco fueled the arrival of more settlers and servants.[66] The headright system tried to solve the labor shortage by providing colonists with land for each indentured servant they transported to Virginia.[67] African workers were first imported to Jamestown in 1619 initially under the rules of indentured servitude. The shift to a system of African slavery in Virginia was propelled by the legal cases of John Punch, who was sentenced to lifetime slavery in 1640 for attempting to run away,[68] and of John Casor, who was claimed by Anthony Johnson as his servant for life in 1655.[69] Slavery first appears in Virginia statutes in 1661 and 1662, when a law made it hereditary based on the mother's status.[70]

Tensions and the geographic differences between the working and ruling classes led to Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, by which time current and former indentured servants made up as much as 80% of the population.[71] Rebels, largely from the colony's frontier, were also opposed to the conciliatory policy towards native tribes, and one result of the rebellion was the signing at Middle Plantation of the Treaty of 1677, which made the signatory tribes tributary states and was part of a pattern of appropriating tribal land by force and treaty. Middle Plantation saw the founding of The College of William & Mary in 1693 and was renamed Williamsburg as it became the colonial capital in 1699.[72] In 1747, a group of Virginian speculators formed the Ohio Company, with the backing of the British crown, to start English settlement and trade in the Ohio Country west of the Appalachian Mountains.[73] France, which claimed this area as part of their colony of New France, viewed this as a threat, and the ensuing French and Indian War became part of the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). A militia from several British colonies, called the Virginia Regiment, was led by then-Lieutenant Colonel George Washington.[74]

Statehood

[edit]

The British Parliament's efforts to levy new taxes following the French and Indian War were deeply unpopular in the colonies. In the House of Burgesses, opposition to taxation without representation was led by Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee, among others.[75] Virginians began to coordinate their actions with other colonies in 1773, and sent delegates to the Continental Congress the following year.[76] After the House of Burgesses was dissolved by the royal governor in 1774, Virginia's revolutionary leaders continued to govern via the Virginia Conventions. On May 15, 1776, the Convention declared Virginia's independence from the British Empire and adopted George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights, which was then included in a new constitution.[77] Another Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, drew upon Mason's work in drafting the national Declaration of Independence.[78]

When the American Revolutionary War began, George Washington was selected to head the colonial army. During the war, the capital was moved to Richmond at the urging of Governor Thomas Jefferson, who feared that Williamsburg's coastal location would make it vulnerable to British attack.[79] In 1781, the combined action of Continental and French land and naval forces trapped the British army on the Virginia Peninsula, where troops under George Washington and Comte de Rochambeau defeated British General Cornwallis in the Siege of Yorktown. His surrender on October 19, 1781 led to peace negotiations in Paris and secured the independence of the colonies.[80]

Virginians were instrumental in writing the United States Constitution. James Madison drafted the Virginia Plan in 1787 and the Bill of Rights in 1789.[78] Virginia ratified the Constitution on June 25, 1788. The three-fifths compromise ensured that Virginia, with its large number of slaves, initially had the largest bloc in the House of Representatives. Together with the Virginia dynasty of presidents, this gave the Commonwealth national importance. In 1790, both Virginia and Maryland ceded territory to form the new District of Columbia, though the Virginian area was retroceded in 1846.[81] Virginia is called "Mother of States" because of its role in being carved into states like Kentucky, which became the 15th state in 1792, and for the numbers of American pioneers born in Virginia.[82]

Civil War and aftermath

[edit]

In addition to agriculture, slave labor was increasingly used in mining, shipbuilding and other industries.[83] The execution of Gabriel Prosser in 1800, Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831 and John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 marked the growing social discontent over slavery and its role in the plantation economy. By 1860, almost half a million people, roughly 31% of the total population of Virginia, were enslaved.[84][85] This division contributed to the start of the American Civil War.

Virginia voted to secede from the United States on April 17, 1861, after the Battle of Fort Sumter and Abraham Lincoln's call for volunteers. On April 24, Virginia joined the Confederate States of America, which chose Richmond as its capital.[82] After the 1861 Wheeling Convention, 48 counties in the northwest separated to form a new state of West Virginia, which chose to remain loyal to the Union. Virginian general Robert E. Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia in 1862, and led invasions into Union territory, ultimately becoming commander of all Confederate forces. During the war, more battles were fought in Virginia than anywhere else, including Bull Run, the Seven Days Battles, Chancellorsville, and the concluding Battle of Appomattox Court House.[86] After the capture of Richmond in April 1865, the state capital was briefly moved to Lynchburg,[87] while the Confederate leadership fled to Danville.[88] Virginia was formally restored to the United States in 1870, due to the work of the Committee of Nine.[89]

During the post-war Reconstruction era, Virginia adopted a constitution which provided for free public schools, and guaranteed political, civil, and voting rights.[90] The populist Readjuster Party ran an inclusive coalition until the conservative white Democratic Party gained power after 1883.[91] It passed segregationist Jim Crow laws and in 1902 rewrote the Constitution of Virginia to include a poll tax and other voter registration measures that effectively disfranchised most African Americans and many poor whites.[92] Though their schools and public services were segregated and underfunded due to a lack of political representation, African Americans were able to unite in communities and take a greater role in Virginia society.[93]

Modern era

[edit]

New economic forces also changed the Commonwealth. Virginian James Albert Bonsack invented the tobacco cigarette rolling machine in 1880 leading to new industrial scale production centered around Richmond. In 1886, railroad magnate Collis Potter Huntington founded Newport News Shipbuilding, which was responsible for building six major World War I-era battleships for the U.S. Navy from 1907–1923.[94] During the war, German submarines like U-151 attacked ships outside the port.[95] In 1926, Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, rector of Williamsburg's Bruton Parish Church, began restoration of colonial-era buildings in the historic district with financial backing of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.[96] Though their project, like others in the state, had to contend with the Great Depression and World War II, work continued as Colonial Williamsburg became a major tourist attraction.[97]

Protests started by Barbara Rose Johns in 1951 in Farmville against segregated schools led to the lawsuit Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County. This case, filed by Richmond natives Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, was decided in 1954 with Brown v. Board of Education, which rejected the segregationist doctrine of "separate but equal". But, in 1958, under the policy of "massive resistance" led by the influential segregationist Senator Harry F. Byrd and his Byrd Organization, the Commonwealth prohibited desegregated local schools from receiving state funding.[98]

The Civil Rights Movement gained many participants in the 1960s. It achieved the moral force and support to gain passage of national legislation with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In 1964 the United States Supreme Court ordered Prince Edward County and others to integrate schools.[99] In 1967, the Court also struck down the state's ban on interracial marriage with Loving v. Virginia. From 1969 to 1971, state legislators under Governor Mills Godwin rewrote the constitution, after goals such as the repeal of Jim Crow laws had been achieved. In 1989, Douglas Wilder became the first African American elected as governor in the United States.[100]