Colonoscopy

| Colonoscopy | |

|---|---|

Colonoscopy being performed | |

| ICD-9-CM | 45.23 |

| MeSH | D003113 |

| OPS-301 code | 1-650 |

| MedlinePlus | 003886 |

Colonoscopy (/ˌkɒləˈnɒskəpi/) or coloscopy (/kəˈlɒskəpi/)[1] is a medical procedure involving the endoscopic examination of the large bowel (colon) and the distal portion of the small bowel. This examination is performed using either a CCD camera or a fiber optic camera, which is mounted on a flexible tube and passed through the anus.[2][3]

The purpose of a colonoscopy is to provide a visual diagnosis via inspection of the internal lining of the colon wall, which may include identifying issues such as ulceration or precancerous polyps, and to enable the opportunity for biopsy or the removal of suspected colorectal cancer lesions.[4][5]

Colonoscopy is similar in principle to sigmoidoscopy, with the primary distinction being the specific parts of the colon that each procedure can examine. The same instrument used for sigmoidoscopy performs the colonoscopy. A colonoscopy permits a comprehensive examination of the entire colon, which is typically around 1,200 to 1,500 millimeters in length.[6]

In contrast, a sigmoidoscopy allows for the examination of only the distal portion of the colon, which spans approximately 600 millimeters.[7] This distinction is medically significant because the benefits of colonoscopy in terms of improving cancer survival have primarily been associated with the detection of lesions in the distal portion of the colon.[8]

Routine use of colonoscopy screening varies globally. In the US, colonoscopy is a commonly recommended and widely utilized screening method for colorectal cancer, often beginning at age 45 or 50, depending on risk factors and guidelines from organizations like the American Cancer Society.[9] However, screening practices differ worldwide. For example, in the European Union, several countries primarily employ fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) or sigmoidoscopy for population-based screening.[10] These variations stem from differences in healthcare systems, policies, and cultural factors. Recent studies[11] have stressed the need for screening strategies and awareness campaigns to combat colorectal cancer - on a global scale.[12][13]

Medical uses

[edit]

Conditions that call for colonoscopies include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, unexplained changes in bowel habit and suspicion of malignancy.[14] Colonoscopies are often used to diagnose colon polyp and colon cancer,[15] but are also frequently used to diagnose inflammatory bowel disease.[16][17]

Another common indication for colonoscopy is the investigation of iron deficiency with or without anaemia. The examination of the colon, to rule out a lesion contributing to blood loss, along with an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (gastroscopy) to rule out oesophageal, stomach, and proximal duodenal sources of blood loss.

Fecal occult blood is a quick test which can be done to test for microscopic traces of blood in the stool. A positive test is almost always an indication to do a colonoscopy. In most cases the positive result is just due to hemorrhoids; however, it can also be due to diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis), colon cancer, or polyps. Colonic polypectomy has become a routine part of colonoscopy, allowing quick and simple removal of polyps during the procedure, without invasive surgery.[18]

With regard to blood in the stool either visible or occult, it is worthy of note, that occasional rectal bleeding may have multiple non-serious potential causes.[19]

Colon cancer screening

[edit]Colonoscopy is one of the colorectal cancer screening tests available to people in the US who are 45 years of age and older. The other screening tests include flexible sigmoidoscopy, double-contrast barium enema, computed tomographic (CT) colonography (virtual colonoscopy), guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and multitarget stool DNA screening test (Cologuard).[20]

Subsequent rescreenings are then scheduled based on the initial results found, with a five- or ten-year recall being common for colonoscopies that produce normal results.[21][22] People with a family history of colon cancer are often first screened during their teenage years. Among people who have had an initial colonoscopy that found no polyps, the risk of developing colorectal cancer within five years is extremely low. Therefore, there is no need for those people to have another colonoscopy sooner than five years after the first screening.[23][24]

Some medical societies in the US recommend a screening colonoscopy every 10 years beginning at age 50 for adults without increased risk for colorectal cancer.[25] Research shows that the risk of cancer is low for 10 years if a high-quality colonoscopy does not detect cancer, so tests for this purpose are indicated every ten years.[25][26]

Colonoscopy screening is associated with approximately two-thirds fewer deaths due to colorectal cancers on the left side of the colon, and is not associated with a significant reduction in deaths from right-sided disease. It is speculated that colonoscopy might reduce rates of death from colon cancer by detecting some colon polyps and cancers on the left side of the colon early enough that they may be treated, and a smaller number on the right side.[27]

Since polyps often take 10 to 15 years to transform into cancer in someone at average risk of colorectal cancer, guidelines recommend 10 years after a normal screening colonoscopy before the next colonoscopy. (This interval does not apply to people at high risk of colorectal cancer or those who experience symptoms of the disease.)[28][29]

The large randomized pragmatic clinical trial NordICC was the first published trial on the use of colonoscopy as a screening test to prevent colorectal cancer, related death, and death from any cause. It included 84,585 healthy men and women aged 55 to 64 years in Poland, Norway, and Sweden, who were randomized to either receive an invitation to undergo a single screening colonoscopy (invited group) or to receive no invitation or screening (usual-care group). Of the 28,220 people in the invited group, 11,843 (42.0%) underwent screening. A total of 15 people who underwent colonoscopy (0.13%) had major bleeding after polyp removal.

None of the participants experienced a colon perforation due to colonoscopy. After 10 years, an intention-to-screen analysis showed a significant relative risk reduction of 18% in the risk of colorectal cancer (0.98% in the invited group vs. 1.20% in the usual-care group). The analysis showed no significant change in the risk of death from colorectal cancer (0.28% vs. 0.31%) or in the risk of death from any cause (11.03% vs. 11.04%). To prevent one case of colorectal cancer, 455 invitations to colonoscopy were required.[30][31]

As of 2023, the CONFIRM trial, a randomized trial evaluating colonoscopy vs. FIT is currently ongoing.[32]

In 2021, the US spent $43 billion on cancer screening to prevent five cancers, with colonoscopies accounting for 55% of the total.[33] The death rate from colon cancer has been on a linear decline for 40 years, falling by nearly 50 percent from the 1980s (when few were screened) to 2024; however, the increase in screening did not accelerate the decline.[34] Therefore, resources devoted to cancer screening would be better directed toward ensuring widespread access to effective cancer treatment.[35]

Recommendations

[edit]The American Cancer Society issues recommendations on colorectal cancer screening guidelines. These guidelines often change and are updated as new studies and technologies have become available[9]

Many other national organizations also issue such guidance, such as the UK's NHS[36] and various European agencies,[37] guidance can vary between such agencies.

Medicare coverage

[edit]In the United States, Medicare insurance covers a number of colorectal-cancer screening tests.[38]

Procedural risks

[edit]The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy estimates around three in 1,000 colonoscopies lead to serious complications.[39]

Perforation

[edit]The most serious complication is generally gastrointestinal perforation, which is life-threatening and requires immediate surgical intervention.[40]

The key to managing a colonoscopic perforation is diagnosis at the time. Typically, the reasons are that the bowel prep done to facilitate the examination acts to reduce the potential for contamination, resulting in a higher likelihood of conservative management. In addition, detection at the time allows the physician to deploy strategies to seal the colon, or mark it should the patient require surgery.

Issues from general anesthesia

[edit]As with any procedure involving anaesthesia, complications can occur, such as:[41][42]

- allergic reactions,

- cardiovascular issues,

- paradoxical agitation,

- aspiration,

- dental injury.

Colon preparation electrolyte issues

[edit]Electrolyte imbalance caused by bowel preparation solutions is possible, but current bowel cleansing laxatives are formulated to account for electrolyte balance, making this a very rare event.[43]

Other

[edit]During colonoscopies, when a polyp is removed (a polypectomy), the risk of complication increases.[44][45] One of the most serious complications is postpolypectomy coagulation syndrome, occurring in 1 in 1000 procedures.[46] It results from a burn injury to the wall of the colon causing abdominal pain, fever, elevated white blood cell count and elevated serum C-reactive protein. Treatment consists of intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and avoiding oral intake of food, water, etc. until symptoms improve. Risk factors include right colon polypectomy, large polyp size (>2 cm), non-polypoid lesions (laterally spreading lesions), and hypertension.[47]

Although rare, infections of the colon are a potential colonoscopy risk. The colon is not a sterile environment, and infections can occur during biopsies from what is essentially a 'small shallow cut', enabling bacterial intrusion into lower parts of the colon wall. In cases where the lining of the colon is perforated, bacteria can infiltrate the abdominal cavity.[48] Infection may also be introduced if the endoscope is not cleaned and sterilized appropriately between procedures.

Minor colonoscopy risks may include nausea, vomiting or allergies to the sedatives that may have been used. If medication is given intravenously, the vein may become irritated, or mild phlebitis may occur.[49]

Technique

[edit]Preparation

[edit]The colon must be free of solid matter for the test to be performed properly.[50] For one to three days, the patient is required to follow a low fiber or clear-liquid-only diet. Examples of clear fluids are apple juice, chicken and/or beef broth or bouillon, lemon-lime soda, lemonade, sports drink, and water. It is important that the patient remains hydrated. Sports drinks contain electrolytes which are depleted during the purging of the bowel. Drinks containing fiber such as prune and orange juice should not be consumed, nor should liquids dyed red, purple, orange, or sometimes brown; however, cola is allowed. In most cases, tea or coffee taken without milk are allowed.[51][52]

The day before the colonoscopy (or colorectal surgery), the patient is either given a laxative preparation (such as bisacodyl, phospho soda, sodium picosulfate, or sodium phosphate and/or magnesium citrate) and large quantities of fluid, or whole bowel irrigation is performed using a solution of polyethylene glycol and electrolytes.[53][54] The procedure may involve both a pill-form laxative and a bowel irrigation preparation with the polyethylene glycol powder dissolved into any clear liquid, such as a sports drink that contains electrolytes.

The patient may be asked not to take aspirin or similar products such as salicylate, ibuprofen, etc. for up to ten days before the procedure to avoid the risk of bleeding if a polypectomy is performed during the procedure. A blood test may be performed before the procedure.[55]

Procedure

[edit]

During the procedure, the patient is often given sedation intravenously, employing agents such as fentanyl or midazolam. Although meperidine (Demerol) may be used as an alternative to fentanyl, the concern of seizures has relegated this agent to second choice for sedation behind the combination of fentanyl and midazolam. The average person will receive a combination of these two drugs, usually between 25 and 100 μg IV fentanyl and 1–4 mg IV midazolam. Sedation practices vary between practitioners and nations; in some clinics in Norway, sedation is rarely administered.[56][57]

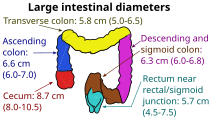

The first step is usually a digital rectal examination (DRE), to examine the tone of the anal sphincter and to determine if preparation has been adequate. A DRE is also useful in detecting anal neoplasms and the clinician may note issues with the prostate gland in men undergoing this procedure.[58] The endoscope is then passed through the anus up the rectum, the colon (sigmoid, descending, transverse and ascending colon, the cecum), and ultimately the terminal ileum. The endoscope has a movable tip and multiple channels for instrumentation, air, suction and light. The bowel is occasionally insufflated with air to maximize visibility (a procedure that gives the patient the false sensation of needing to take a bowel movement). Biopsies are frequently taken for histology. Additionally in a procedure known as chromoendoscopy, a contrast-dye (such as indigo carmine) may be sprayed through the endoscope onto the bowel wall to help visualize any abnormalities in the mucosal morphology. A Cochrane review updated in 2016 found strong evidence that chromoscopy enhances the detection of cancerous tumors in the colon and rectum.[59]

In most experienced hands, the endoscope is advanced to the junction of where the colon and small bowel join up (cecum) in under 10 minutes in 95% of cases. Due to tight turns and redundancy in areas of the colon that are not "fixed", loops may form in which advancement of the endoscope creates a "bowing" effect that causes the tip to actually retract. These loops often result in discomfort due to stretching of the colon and its associated mesentery. Manoeuvres to "reduce" or remove the loop include pulling the endoscope backwards while twisting it. Alternatively, body position changes and abdominal support from external hand pressure can often "straighten" the endoscope to allow the scope to move forward. In a minority of patients, looping is often cited as a cause for an incomplete examination. Usage of alternative instruments leading to completion of the examination has been investigated, including use of pediatric colonoscope, push enteroscope and upper GI endoscope variants.[60]

Lawsuits over missed cancerous lesions have recently prompted some institutions to better document endoscope examination times, as rapid examination times may be a source of potential medical legal liability.[61] This is often a real concern in clinical settings where high caseloads could provide financial incentive to complete colonoscopies as quickly as possible.

- Polyp is identified.

- A sterile solution is injected under the polyp to lift it away from deeper tissues.

- A portion of the polyp is now removed.

- The polyp is fully removed.

Patient comfort and pain management

[edit]The pain associated with the procedure is not caused by the insertion of the scope but rather by the inflation of the colon in order to do the inspection. The scope itself is essentially a long, flexible tube about a centimeter in diameter — that is, as big around as the little finger, which is less than the diameter of an average stool.[62]

The colon is wrinkled and corrugated, somewhat like an accordion or a clothes-dryer exhaust tube, which gives it the large surface area needed for nutrition and water absorption. In order to inspect this surface thoroughly, the physician blows it up like a balloon, using air from a compressor or carbon dioxide from a gas bottle (CO2 is absorbed into the bloodstream through the mucosal lining of the colon much faster than air and then exhaled through the lungs which is associated with less post procedural pain), in order to get the creases out.

The colon has sensors that can tell when there is unexpected gas pushing the colon walls out—which may cause mild discomfort. Usually, total anesthesia or a partial twilight sedative are used to reduce the patient's awareness of pain or discomfort, or just the unusual sensations of the procedure. Once the colon has been inflated, the doctor inspects it with the scope as it is slowly pulled backward. If any polyps are found they are then cut out for later biopsy.[63]

Colonoscopy can be carried out without any sedation and a number of studies have been performed evaluating colonoscopy outcomes without sedation.[64] Though in the US and EU the procedure is usually carried out with some form of sedation.[1]

Economics

[edit]Researchers have found that older patients with three or more significant health problems (i.e., dementia or heart failure) had higher rates of repeat colonoscopies without medical indications. These patients are less likely to live long enough to develop colon cancer.[65]

History

[edit]In the 1960s, Niwa and Yamagata at Tokyo University developed the fibre-optic endoscopy device.[66] After 1968, William Wolff and Hiromi Shinya pioneered the development of the colonoscope.[67] Their invention, in 1969 in Japan, was a significant advance over the barium enema and the flexible sigmoidoscope because it allowed for the visualization and removal of polyps from the entire colon. Wolff and Shinya advocated for their invention and published much of the early evidence needed to overcome skepticism about the device's safety and efficacy.[68]

Some of the leading medical device companies in the colonoscopy market as of 2023 include: Fujifilm, Karl Storz SE, Pro Scope Systems, Olympus Corporation, Medtronic Plc, Steris and Pentax Medical.[69][better source needed]

Etymology

[edit]The terms colonoscopy[70][71][72] or coloscopy[71] are derived from[71] the ancient Greek noun κόλον, same as English colon,[73] and the verb σκοπεῖν, look (in)to, examine.[73] The term colonoscopy is however ill-constructed,[74] as this form supposes that the first part of the compound consists of a possible root κολων- or κολον-, with the connecting vowel -o, instead of the root κόλ- of κόλον.[74] A compound such as κολωνοειδής, like a hill,[73] (with the additional -on-) is derived from the ancient Greek word κολώνη or κολωνός, hill.[73] Similarly, colonoscopy (with the additional -on-) can literally be translated as examination of the hill,[74] instead of the examination of the colon.

In English, multiple words exist that are derived from κόλον, such as colectomy,[71][75] colocentesis,[71] colopathy,[71] and colostomy[71] among many others, that actually lack the incorrect additional -on-. A few compound words such as colonopathy have doublets with -on- inserted.[71][72]

Society and culture

[edit]The procedure of colonoscopy gained national attention in the United States in 1985 when President Ronald Reagan underwent a life-saving colonoscopy.[76][77][78]

A survey on colonoscopy shows a poor understanding of its protective value and widespread misconceptions. The public has perceptual gaps around the purpose of colonoscopies, the subjective experience of the colonoscopy procedure, and the quantity of bowel preparation needed.[79]

Actors Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney have used their social media platform to raise awareness about the importance of colonoscopy as a procedure for colon cancer screening. They filmed their own colonoscopies as part of a campaign called "Lead From Behind",[80][81] demonstrating that the procedure can be both easy and lifesaving.[82][83]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Colonoscopy". The American Heritage Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Company. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2012 – via thefreedictionary.com.

- ^ "Recommendation: Colorectal Cancer: Screening | United States Preventive Services Taskforce". www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Colonoscopy - NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Orr L. "Do Colonoscopies Prevent Colon Cancer?". URMC Newsroom. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Waye JD, Aisenberg J, Rubin PH (18 April 2013). Practical Colonoscopy (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118553442. ISBN 978-0-470-67058-3. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Small & Large Intestine Whereas a sigmoidoscopy is purposefully examining only the distal (left) side of the colon". SEER Training. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "Flexible sigmoidoscopy". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Recommendation: Colorectal Cancer: Screening". United States Preventive Services Task Force. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Colorectal Cancer Guideline". www.cancer.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "Statement on the Council cancer screening recommendations". FEAM. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Wong MC, Huang J, Liang PS (October 2023). "Is the practice of colorectal cancer screening questionable after the NordICC trial was published?". Clinical and Translational Medicine. 13 (10): e1365. doi:10.1002/ctm2.1365. PMC 10550029. PMID 37792640.

- ^ Audibert C, Perlaky A, Glass D (September 2017). "Global perspective on colonoscopy use for colorectal cancer screening: A multi-country survey of practicing colonoscopists". Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications. 7: 116–121. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2017.06.008. PMC 5898517. PMID 29696175.

- ^ Hayman CV, Vyas D (January 2021). "Screening colonoscopy: The present and the future". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 27 (3): 233–239. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i3.233. PMC 7814366. PMID 33519138.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer Signs and Symptoms". www.cancer.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "Colonoscopy". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ "Colonoscopy". Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. 7 December 2021. Archived from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Passos MA, Chaves FC, Chaves-Junior N (2 July 2018). "The Importance of Colonoscopy in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases". Arquivos Brasileiros de Cirurgia Digestiva. 31 (2): e1374. doi:10.1590/0102-672020180001e1374. PMC 6044200. PMID 29972402.

- ^ Sivak MV (December 2004). "Polypectomy: looking back". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 60 (6): 977–982. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02380-6. PMID 15605015.

- ^ "Rectal Bleeding: What It Means & When to Worry". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Early Detection" (PDF). American Cancer Society. 5 February 2015. pp. 16–24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ^ Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, et al. (June 2002). "Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 97 (6): 1296–1308. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05812.x. PMID 12094842. S2CID 26250449.

- ^ Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, et al. (July 2017). "Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 112 (7). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1016–1030. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.174. PMID 28555630. S2CID 6808521.

- ^ Imperiale TF, Glowinski EA, Lin-Cooper C, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF (September 2008). "Five-year risk of colorectal neoplasia after negative screening colonoscopy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (12): 1218–1224. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0803597. PMID 18799558.

- ^ No Need to Repeat Colonoscopy Until 5 Years After First Screening Archived 16 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine Newswise, Retrieved on 17 September 2008.

- ^ a b Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, et al. (February 2003). "Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence". Gastroenterology. 124 (2): 544–560. doi:10.1053/gast.2003.50044. PMID 12557158.

- ^ American Gastroenterological Association, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Gastroenterological Association, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2012, retrieved 17 August 2012

- ^ Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L (January 2009). "Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (1): 1–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00306. PMID 19075198. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Interval between Colonoscopies May be Shorter than Recommended". Cancerconnect. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Goodwin JS, Singh A, Reddy N, Riall TS, Kuo YF (August 2011). "Overuse of screening colonoscopy in the Medicare population". Archives of Internal Medicine. 171 (15): 1335–1343. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.212. PMC 3856662. PMID 21555653. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ Bretthauer M, Løberg M, Wieszczy P, Kalager M, Emilsson L, Garborg K, et al. (October 2022). "Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death". The New England Journal of Medicine. 387 (17): 1547–1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208375. hdl:10852/101829. PMID 36214590. S2CID 252778114.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT00883792 for "The Northern-European Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (NordICC)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ "Colonoscopy Versus Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality From Colorectal Cancer (CONFIRM) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Halpern MT, Liu B, Lowy DR, Gupta S, Croswell JM, Doria-Rose VP (2024). "The Annual Cost of Cancer Screening in the United States". Annals of Internal Medicine. 177 (9): 1170–1178. doi:10.7326/M24-0375. PMID 39102723.

- ^ Kolata G (August 7, 2024). "$43 Billion Price Tag on Cancer Screening Each Year Spurs Debate". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Welch HG (2024). "Dollars and Sense: The Cost of Cancer Screening in the United States". Annals of Internal Medicine. 177 (9): 1275–1276. doi:10.7326/M24-0887. PMID 39102720.

- ^ "Bowel cancer screening: guidelines for colonoscopy". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Bénard F, Barkun AN, Martel M, von Renteln D (January 2018). "Systematic review of colorectal cancer screening guidelines for average-risk adults: Summarizing the current global recommendations". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 24 (1): 124–138. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.124. PMC 5757117. PMID 29358889.

- ^ "Colonoscopy Screening Coverage". www.medicare.gov. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "Are Colonoscopies Dangerous?". Colorectal Cancer Alliance. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Sartelli M, Viale P, Catena F, Ansaloni L, Moore E, Malangoni M, et al. (January 2013). "2013 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections". World Journal of Emergency Surgery (Review). 8 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1749-7922-8-3. PMC 3545734. PMID 23294512.

- ^ "Anesthesia Risk Assessment". Made For This Moment. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ Smith G, D'Cruz JR, Rondeau B, Goldman J (2023), "General Anesthesia for Surgeons", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29630251, archived from the original on 26 March 2023, retrieved 10 November 2023

- ^ Costelha J, Dias R, Teixeira C, Aragão I (26 August 2019). "Hyponatremic Coma after Bowel Preparation". European Journal of Case Reports in Internal Medicine. 6 (9): 001217. doi:10.12890/2019_001217. PMC 6774655. PMID 31583213.

- ^ Choo WK, Subhani J (2012). "Complication rates of colonic polypectomy in relation to polyp characteristics and techniques: a district hospital experience". Journal of Interventional Gastroenterology. 2 (1): 8–11. doi:10.4161/jig.20126. ISSN 2154-1280. PMC 3350902. PMID 22586542.

- ^ Tomaszewski M, Sanders D, Enns R, Gentile L, Cowie S, Nash C, et al. (12 October 2021). "Risks associated with colonoscopy in a population-based colon screening program: an observational cohort study". CMAJ Open. 9 (4): E940 – E947. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200192. ISSN 2291-0026. PMC 8513602. PMID 34642256.

- ^ Jehangir A, Bennett KM, Rettew AC, Fadahunsi O, Shaikh B, Donato A (19 October 2015). "Post-polypectomy electrocoagulation syndrome: a rare cause of acute abdominal pain". Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives. 5 (5): 10.3402/jchimp.v5.29147. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v5.29147. ISSN 2000-9666. PMC 4612487. PMID 26486121.

- ^ Anderloni A, Jovani M, Hassan C, Repici A (30 August 2014). "Advances, problems, and complications of polypectomy". Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 7: 285–296. doi:10.2147/CEG.S43084. PMC 4155740. PMID 25210470.

- ^ "Bowel Infections". Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "What to expect after a colonoscopy?". Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, et al. (October 2014). "Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer". Gastroenterology. 147 (4). Elsevier BV: 903–924. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.002. PMID 25239068.

- ^ "Preparing for Your Colonoscopy: Types of Kits & Instructions". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ Parra-Blanco A, Nicolas-Perez D, Gimeno-Garcia A, Grosso B, Jimenez A, Ortega J, et al. (October 2006). "The timing of bowel preparation before colonoscopy determines the quality of cleansing, and is a significant factor contributing to the detection of flat lesions: a randomized study". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (38): 6161–6166. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6161. PMC 4088110. PMID 17036388.

- ^ Hung SY, Chen HC, Chen WT (March 2020). "A Randomized Trial Comparing the Bowel Cleansing Efficacy of Sodium Picosulfate/Magnesium Citrate and Polyethylene Glycol/Bisacodyl (The Bowklean Study)". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 5604. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.5604H. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-62120-w. PMC 7101403. PMID 32221332.

- ^ Kumar AS, Kelleher DC, Sigle GW (September 2013). "Bowel Preparation before Elective Surgery". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 26 (3): 146–152. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1351129. PMC 3747288. PMID 24436665.

- ^ "Colyte/Trilyte Colonoscopy Preparation" (PDF). Palo Alto Medical Foundation. June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ Bretthauer M, Hoff G, Severinsen H, Erga J, Sauar J, Huppertz-Hauss G (May 2004). "[Systematic quality control programme for colonoscopy in an endoscopy centre in Norway]". Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening (in Norwegian). 124 (10): 1402–1405. PMID 15195182.

- ^ Dossa F, Dubé C, Tinmouth J, Sorvari A, Rabeneck L, McCurdy BR, et al. (16 February 2020). "Practice recommendations for the use of sedation in routine hospital-based colonoscopy". BMJ Open Gastroenterology. 7 (1): e000348. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000348. PMC 7039579. PMID 32128226.

- ^ Farooq O, Farooq A, Ghosh S, Qadri R, Steed T, Quinton M, et al. (July 2021). "The Digital Divide: A Retrospective Survey of Digital Rectal Examinations during the Workup of Rectal Cancers". Healthcare. 9 (7): 855. doi:10.3390/healthcare9070855. PMC 8306048. PMID 34356233.

- ^ Brown SR, Baraza W, Din S, Riley S (April 2016). "Chromoscopy versus conventional endoscopy for the detection of polyps in the colon and rectum". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (4): CD006439. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006439.pub4. PMC 8749964. PMID 27056645.

- ^ Lichtenstein GR, Park PD, Long WB, Ginsberg GG, Kochman ML (January 1999). "Use of a push enteroscope improves ability to perform total colonoscopy in previously unsuccessful attempts at colonoscopy in adult patients". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 94 (1): 187–190. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00794.x. PMID 9934753. S2CID 24536782. Note:Single use PDF copy provided free by Blackwell Publishing for purposes of Wikipedia content enrichment.

- ^ Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL (December 2006). "Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (24): 2533–2541. doi:10.1056/nejmoa055498. PMID 17167136.

- ^ Ekkelenkamp VE, Dowler K, Valori RM, Dunckley P (April 2013). "Patient comfort and quality in colonoscopy". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (15): 2355–2361. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2355. PMC 3631987. PMID 23613629.

- ^ Brown S, Whitlow CB (1 March 2017). "Patient comfort during colonoscopy". Seminars in Colon and Rectal Surgery. SI: Advanced Endoscopy Outline. 28 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1053/j.scrs.2016.11.004. ISSN 1043-1489. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Zhang K, Yuan Q, Zhu S, Xu D, An Z (April 2018). "Is Unsedated Colonoscopy Gaining Ground Over Sedated Colonoscopy?". Journal of the National Medical Association. 110 (2): 143–148. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2016.12.003. PMID 29580447.

- ^ "Health and Economic Benefits of Colorectal Cancer Interventions". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 16 March 2023. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Wawrzynczak E (16 February 2019). "50 Years of Fibre-optic Colonoscopy". British Society for the History of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Wolff WI (September 1989). "Colonoscopy: history and development". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 84 (9): 1017–1025. PMID 2672788.

- ^ Martin D (2 September 2011). "Dr. William Wolff, Colonoscopy Co-Developer, Dies at 94". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Lowden O. "Top companies and takeaways of the endoscopy devices industry". blog.bccresearch.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Dorland WA, Miller EC (1948). The American illustrated medical dictionary (21st ed.). Philadelphia/London: W.B. Saunders Company.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dirckx JH, ed. (1997). Stedman's concise medical dictionary for the health professions (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ a b Anderson DM (2000). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (29th ed.). Philadelphia/London/Toronto/Montreal/Sydney/Tokyo: W.B. Saunders Company.

- ^ a b c d Liddell HG, Scott R (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b c Anastassiades CP, Cremonini F, Hadjinicolaou D (2008). "Colonoscopy and colonography: back to the roots". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 12 (6): 345–347. PMID 19146195.

- ^ Foster, F.D. (1891-1893). An illustrated medical dictionary. Being a dictionary of the technical terms used by writers on medicine and the collateral sciences, in the Latin, English, French, and German languages. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ^ Wiedeman JE (June 2009). "Presidential operations: medical fact or urban legend?". J Am Coll Surg. 208 (6): 1132–7. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.024. PMID 19476902.

- ^ Selby JV (September 2000). "Explaining recent declines in colorectal cancer incidence: was it the sigmoidoscope?". Am J Med. 109 (4): 332–4. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00540-4. PMID 10996587.

- ^ Gilbert RE (2014). "The politics of presidential illness. Ronald Reagan and the Iran-Contra Scandal". Politics Life Sci. 33 (2): 58–76. doi:10.2990/33_2_58. PMID 25901884. S2CID 41674696.

- ^ Amlani B, Radaelli F, Bhandari P (2020). "A survey on colonoscopy shows poor understanding of its protective value and widespread misconceptions across Europe". PLOS ONE. 15 (5): e0233490. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1533490A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233490. PMC 7241766. PMID 32437402.

- ^ "Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney Share Their Colonoscopy Videos To Encourage People to 'Lead From Behind'". Colorectal Cancer Alliance. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Ryan Reynolds And Rob McElhenney Film Each Other Getting Colonoscopies". UPROXX. 13 September 2022. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney get a colonoscopy on camera to raise awareness". 14 September 2022. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Celebrity Actors Film Their Colonoscopies to Bring Awareness". Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, et al. (March 2020). "Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". Gastroenterology. 158 (4): 1131–1153.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.026. PMC 7672705. PMID 32044092.

- Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, et al. (March 2020). "Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 115 (3): 415–434. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000544. PMC 7393611. PMID 32039982.

- Joseph DA, King JB, Dowling NF, Thomas CC, Richardson LC (March 2020). "Vital Signs: Colorectal Cancer Screening Test Use - United States, 2018". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (10): 253–259. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6910a1. PMC 7075255. PMID 32163384.

External links

[edit] Media related to Colonoscopy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Colonoscopy at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch