Songtsen Gampo - Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Songtsen Gampo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of Tibet | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Predecessor | Namri Songtsen | ||||||||

| Successor | Mangsong Mangtsen | ||||||||

| Born | Songtsen between 557 and 617 Maizhokunggar, Tibet | ||||||||

| Died | 649 Zal-mo-sgang, 'phun-yul, Tibet (in modern Lhünzhub County) | ||||||||

| Spouse | Pogong Mongza Tricham Bhrikuti (from Nepal, Licchavi kingdom) | ||||||||

| Issue | Gungsong Gungtsen | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Father | Namri Songtsen | ||||||||

| Mother | Driza Tökarma | ||||||||

| Religion | Tibetan Buddhism | ||||||||

Songtsen Gampo (Tibetan: སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ, srong btsan sgam po; 569–649) or Songzan Ganbu (Chinese: 松贊干布), was the 33rd Tibetan king and founder of the Tibetan Empire.[a]

He helped introduce Buddhism to Tibet. He had a Nepali wife named Bhrikuti and a Tang wife named Princess Wencheng. Both of them were Buddhists.[1] He also helped invent the Tibetan alphabet and made Classical Tibetan the official language of Tibet at the time.

He may have been born in 569 or 605. Tibet used their own calendar so we are still trying to figure it out.

As a kid

[change | change source]

Songtsen Gampo was born at Gyama in Meldro, northeast of modern Lhasa. His dad was the Yarlung king Namri Songtsen. The book The Holder of the White Lotus says Gampo was the human form (incarnation) of the Avalokiteśvara. Dalai Lamas are also thought to be human forms of the Avalokitesvara.[2] In the 11th century, Buddhists started calling him a cakravartin and incarnation of Avalokiteśvara.[3]

Family

[change | change source]Some Dunhuang documents say Gampo had a sister Sad-mar-kar and a younger brother. His younger brother was betrayed and died in a fire after 641. There may have been fighting between his sister and brother.[4][5]

Songtsen Gampo's mother was part of the Tsépong clan (Tibetan Annals). She helped unify Tibet. Her name is Driza Tökarma ("the Bri Wife [named] White Skull Woman", Tibetan Annals).[6]

According to Tibetan tradition, Songtsen Gampo became king when 13 after his father was poisoned around 618. He was the 33rd king of the Yarlung Dynasty.[7][8] He was born in the Ox year. Yarlung kings usually took throne at 13. This accords with the tradition that the Yarlung kings took the throne when they were 13, when they were old enough to ride a horse.[9] If this is true, then Gampo may have been born in the Ox year 605 CE. The Old Book of Tang confirms that he "was still a minor when he succeeded to the throne."[7][10]

Gampo's wives and children

[change | change source]Gampo had six wives.[11] Five are listed:

- Pogong Mongza Tricham (Mongza, "the Mong clan wife") was mother of Gungsong Gungtsen.[12]

- a noble woman of the Western Xia known as Minyakza ("Western Xia wife"),[13]

- a noble woman from Zhangzhung.

- Nepali princess Bhrikuti ("the great lady, the Nepalese wife")

- Tang Princess Wencheng (文成)[11]

In Tibetan tradition, these last two wives helped bring Buddhism to Tibet. The two great influences on Tibetan Buddhism are Indo-Nepali and Han Buddhism.

Gampo's son, Gungsong Gungtsen, died before his father. So Gampo's son, Mangsong Mangtsen, took the throne. His mother may have been Wencheng or Mangmoje Trikar.[14] Trikar is mentioned in Genealogy, in a hidden library in the caves in Dunhuang, and the Tibetan Annals, which list the names of the Tibetan emperors, their mothers, and their clans.[15]

Some sources tell a different story. When Gungsong Gungtsen turned 13 (nowadays 12 as Tibet used a different calendar), his dad Gampo retired, so Gungsong ruled for five years. They say Gungsong married 'A-zha Mang-mo-rje when he was thirteen, and they had a son, Mangsong Mangtsen (r. 650-676 CE). Gungsong then died when he was 18. His dad Gampo then took the throne again.[16] Gungsong Gungtsen may be buried at Donkhorda, the site of the royal tombs, to the left of his grandfather Namri Songtsen (gNam-ri Srong-btsan). The dates for these events are very unclear.[17][18][19]

What did he do for Tibet?

[change | change source]He made an Alphabet

[change | change source]Songtsen Gampo sent Thonmi Sambhota to India to create a new alphabet for Classical Tibetan. This led to the first written works, literature, and constitution.[20]

He brought new culture

[change | change source]He brought new culture and tech to Tibet.

The Old Book of Tang (Jiu Tangshu 旧唐书) says in 648 a northern Indian army attacked some some Tang Chinese (including Wang Xuanze). So with the Nepali and Tang, Gampo helped defeat the army and protect the Chinese. In 649, the Tang Emperor Gaozong, a fellow Buddhist, gave him the title Binwang, "Guest King" or Zongwang, "Cloth-tribute King" and 3,000 rolls of colorful silk.[21] Gaozong also gave Gampo "silkworms' eggs, mortars and presses for making wine, and workmen to manufacture paper and ink."[22]

Tools and astrology was imported from Tang and the Western Xia; the dharma and the art of writing came from India; treasures from the Nepalis and the Mongols; laws from the Uyghurs of the Turkic Khaganate to the North.[23]

He introduced Buddhism

[change | change source]

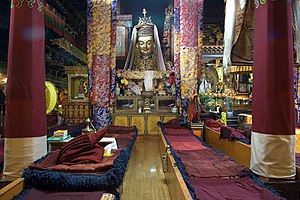

Gampo brought Buddhism to the Tibetan people. He built many Buddhist temples[24][25] During his reign, people began translating Buddhist texts from Sanskrit into Tibetan.[26]

He created a big empire

[change | change source]He defeated the Sumpa in northeastern Tibet around 627 (Tibetan Annals [OTA] l. 2).

He may have conquered the Zhangzhung (around northern India, western Tibet), or that may have happened after he died.[27] The Old Book of Tang say that in 634, the Yangtong (the Zhangzhung) and various Qiang peoples "altogether submitted to him."

He then unified Yangtong, defeated the 'Azha (Tuyuhun), and then conquered two more Qiang tribes before threatening Songzhou with an army of more than 200,000 men.[28]

He conquered the Tangut people (who later formed the Western Xia in 942), the Bailang, and Qiang tribes.[29][30] The Bailang people were west of the Tanguts and east of the Domi. The Tang previously ruled them since 624.[31]

Nepali princess Bhrikuti

[change | change source]The Old Book of Tang says: Naling Deva's father was king of 泥婆羅 Nepal (Licchavi kingdom)[32] died. The king died, and then Naling Deva's uncle took over.[33] "The Tibetans gave [Naling Deva] refuge and reestablished him on his throne [in 641]; that is how he became subject to Tibet."[10][34][35]

The Tibetans traveled to Nepal, and the Naling Deva was happy. Then the Tibetans were attacked by the northern Indian king Harsha.[36] So Naling Deva helped Tibet defeat Harsha's army.[37] Gampo then married Princess Bhrikuti, daughter of Naling Deva.

Tang princess Wencheng

[change | change source]The Jiu Tangshu records that Gampo sent the first embassy from Tibet to the Tang in 634 CE.[38] It was a "tribute mission" with Tibet giving gifts to the Tang. He gave gifts of gold and silk to the Tang emperor and asked for a Tang princess in marriage in return (heqin). Tang said no. So he attacked Songzhou (part of Tang) in 637 and 638.[39] But he then gave up and said sorry. He asked for a wife again, and this time the Tang said yes. And so he married Wencheng, niece of Emperor Taizong of Tang. So there was peace between the Tang and Tibetan empires of China.[40][41]

Both wives Wencheng and Bhrikuti are considered to be Tara, the Goddess of Compassion and female Chenrezig:

- "Dolma, or Drolma (Sanskrit Tara). The two wives of Emperor Srong-btsan gambo are venerated under this name. The Chinese princess is called Dol-kar, of 'the white Dolma,' and the Nepalese princess Dol-jang, or 'the green Dolma.' The latter is prayed to by women for fecundity."[42]

Gampo built a city for Wencheng and a palace just for her.

- "As the princess disliked their custom of painting their faces red, Lungstan (Songtsen Gampo) ordered his people to put a stop to the practice, and it was no longer done. He also discarded his felt and skins, put on brocade and silk, and gradually copied Chinese civilization. He also sent the children of his chiefs and rich men to request admittance into the national school to be taught the classics, and invited learned scholars from China to compose his official reports to the emperor."[43]

Defended Xuanze for China

[change | change source]Chinese monk Xuanzang visited Harsha. Harsha then sent some people to China. China then sent Wang Xuanze and some others back. They traveled through Tibet. Their journey is written in stuff at northern India (Rajgir and Bodhgaya).

Harsha was then overthrown by Arjuna. In 648 Wang Xuanze made a second journey, but Arjuna treated him badly. So the Tibetans and Nepalese defeated Arjuna.[44][45]

So in 649, Chinese emperor Tang Gaozong rewarded Gampo with the title of King of Xinhai Jun (Himalayan plateau, China).

Gampo died in 649.[46] In 650, the Tang emperor sent an envoy with a "letter of mourning and condolences".[47] Gampo's tomb is in the Chongyas Valley near Yalung,[48] 13 m high and 130 m long.[49]

Notes

[change | change source]References

[change | change source]- ↑ Shakabpa 1967.

- ↑ Laird 2006.

- ↑ Dotson 2006, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Ancient Tibet: Research materials from the Yeshe De Project. 1986. Dharma Publishing, California. ISBN 0-89800-146-3, p. 216.

- ↑ Choephel, Gedun. The White Annals. Translated by Samten Norboo. (1978), p. 77. Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, H.P., India.

- ↑ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 161 note 447.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 443.

- ↑ Beckwith 1993, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Vitali, Roberto. 1990. Early Temples of Central Tibet. Serindia Publications, London, p. 70. ISBN 0-906026-25-3

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Snellgrove, David. 1987. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors. 2 Vols. Shambhala, Boston, Vol. II, p. 372.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 302 note 904.

- ↑ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 302 note 913.

- ↑ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 302 note 910.

- ↑ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 200 note 562.

- ↑ Gyatso & Havnevik 2005.

- ↑ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. (1967). Tibet: A Political History, p. 27. Yale University Press. New Haven and London.

- ↑ Ancient Tibet: Research materials from the Yeshe De Project. 1986. Dharma Publishing, California. ISBN 0-89800-146-3, p. 215, 224-225.

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization 1962. Revised English edition, 1972, Faber & Faber, London. Reprint, 1972. Stanford University Press, p. 63. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 cloth; ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 pbk.

- ↑ Gyaltsen, Sakyapa Sonam (1312-1375). The Clear Mirror: A Traditional Account of Tibet's Golden Age, p. 192. Translated by McComas Taylor and Lama Choedak Yuthob. (1996) Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, New York. ISBN 1-55939-048-4.

- ↑ Dudjom 1991.

- ↑ Beckwith (1987), p. 25, n. 71.

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 446.

- ↑ Sakyapa Sonam Gyaltsen. (1328). Clear Mirror on Royal Genealogy. Translated by McComas Taylor and Lama Choedak Yuthok as: The Clear Mirror: A Traditional Account of Tibet's Golden Age, p. 106. (1996) Snow Lion Publications. Ithica, New York. ISBN 1-55939-048-4.

- ↑ Anne-Marie Blondeau, Yonten Gyatso, 'Lhasa, Legend and History,' in Françoise Pommaret(ed.) Lhasa in the seventeenth century: the capital of the Dalai Lamas, Brill Tibetan Studies Library, 3, Brill 2003, pp.15-38, pp15ff.

- ↑ Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa atlas: : traditional Tibetan architecture and townscape, Serindia Publications, Inc., 2001 p.14

- ↑ "Buddhism - Kagyu Office". 2009-01-10. Archived from the original on 2010-02-20.

- ↑ Karmey, Samten G. (1975). "'A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon", p. 180. Memoirs of Research Department of The Toyo Bunko, No, 33. Tokyo.

- ↑ Powers 2004, pp. 168-9

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, pp. 443-444.

- ↑ Beckwith (1987), pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 528, n. 13

- ↑ Pelliot 1961, pg. 12

- ↑ Vitali, Roberto. 1990. Early Temples of Central Tibet. Serindia Publications, London, p. 71. ISBN 0-906026-25-3

- ↑ Chavannes, Édouard . Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux. 1900. Paris, Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient. Reprint: Taipei. Cheng Wen Publishing Co. 1969, p. 186.

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, pp. 529, n. 31.

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization 1962. Revised English edition, 1972, Faber & Faber, London. Reprint, 1972. Stanford University Press, p. 62. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 cloth; ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 pbk., p. 59.

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, pp. 529-530, n. 31.

- ↑ Lee 1981, pp. 6-7

- ↑ Powers 2004, pg. 31

- ↑ Lee 1981, pp. 7-9

- ↑ Pelliot 1961, pp. 3-4

- ↑ Das, Sarat Chandra. (1902), Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet. Reprint: Mehra Offset Press, Delhi. 1988, p. 165, note.

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 545.

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization 1962. Revised English edition, 1972, Faber & Faber, London. Reprint, 1972. Stanford University Press, p. 62. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 cloth; ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 pbk., pp. 58-59

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 446

- ↑ Bacot, J., et al. Documents de Touen-houang relatifs à l'Histoire du Tibet. (1940), p. 30. Libraire orientaliste Paul Geunther, Paris.

- ↑ Lee 1981, p. 13

- ↑ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. Tibet: A Political History (1967), p. 29. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

- ↑ Schaik, Sam Van (2013). Tibet : a history (First published in paperback in 2013. ed.). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. pp. 15. ISBN 978-0-300-19410-4.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch