eIDAS

eIDAS (for "electronic IDentification, Authentication and trust Services") is an EU regulation with the stated purpose of governing "electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions". It passed in 2014 and its provisions came into effect between 2016 and 2018.[1][2]

Description

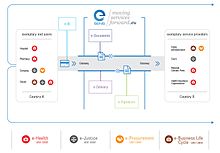

[edit]eIDAS oversees electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the European Union's internal market. It regulates electronic signatures, electronic transactions, involved bodies, and their embedding processes to provide a safe way for users to conduct business online like electronic funds transfer or transactions with public services. Both the signatory and the recipient can have more convenience and security. Instead of relying on traditional methods, such as mail or facsimile, or appearing in person to submit paper-based documents, they may now perform transactions across borders, like "1-Click" technology.[2][3]

eIDAS has created standards for which electronic signatures, qualified digital certificates, electronic seals, timestamps, and other proof for authentication mechanisms enable electronic transactions, with the same legal standing as transactions that are performed on paper.[4]

The regulation came into effect in July 2015, as a means to facilitate secure and seamless electronic transactions within the European Union. Member states are required to recognise electronic signatures that meet the standards of eIDAS.[2][5]

Timeline

[edit]The law was established in EU Regulation 910/2014 of 23 July 2014 on electronic identification and repealed 1999/93/EC from 13 December 1999.[1][2]

It entered into force on 17 September 2014 and applies from 1 July 2016 except for certain articles, which are listed in its Article 52.[6] All organizations delivering public digital services in an EU member state must recognize electronic identification from all EU member states from September 29, 2018. It applied to all countries in the European Single Market.[7][8]

In July 2024, the first eIDAS-Testbed was launched by the go.eIDAS-Association with a number of German tech firms and foundations to issue PID-Credentials to Architecture and Reference Framework (ARF)-compliant wallets.[9]

eIDAS is a result of the European Commission's focus on Europe's Digital Agenda. With the commission's oversight, eIDAS was implemented to spur digital growth within the EU.[10]

The intent of eIDAS is to drive innovation. By adhering to the guidelines set for technology under eIDAS, organisations are pushed towards using higher levels of information security and innovation. Additionally, eIDAS focuses on the following:[5][11]

- Interoperability: Member states are required to create a common framework that will recognize eIDs from other member states and ensure its authenticity and security. That makes it easy for users to conduct business across borders.

- Transparency: eIDAS provides a clear and accessible list of trusted services that may be used within the centralised signing framework. That allows security stakeholders the ability to engage in dialogue about the best technologies and tools for securing digital signatures.

Regulated aspects in electronic transactions

[edit]The Regulation provides the regulatory environment for the following important aspects related to electronic transactions:[2]

- Digital identity: a European-wide framework (European Digital Identity Wallet, EDIW)[12] for digital authentication of citizens, with legal validity. Nine principles of European digital identity have been defined:[13] user choice, privacy, Interoperability and security, trust, convenience, user consent and control proportionality, counterpart knowledge and global scalability.

- Advanced electronic signature (AdES): An electronic signature is considered advanced if it meets certain requirements:

- It provides unique identifying information that links it to its signatory.

- The signatory has sole control of the data used to create the electronic signature.

- It must be capable of identifying if the data accompanying the message has been tampered with after being signed. If the signed data has changed, the signature is marked invalid.

- There is a certificate for electronic signature, electronic proof that confirms the identity of the signatory and links the electronic signature validation data to that person.

- Advanced electronic signatures can be technically implemented, following the XAdES, PAdES, CAdES or ASiC Baseline Profile (Associated Signature Containers) standard for digital signatures, specified by the ETSI.[14]

- Qualified electronic signature, an advanced electronic signature that is created by a qualified electronic signature creation device based on a qualified certificate for electronic signatures.

- Qualified digital certificate for electronic signature, a certificate that attests to a qualified electronic signature's authenticity that has been issued by a qualified trust service provider.

- Qualified website authentication certificate, a qualified digital certificate under the trust services defined in the eIDAS Regulation.

- Trust service, an electronic service that creates, validates, and verifies electronic signatures, time stamps, seals, and certificates. Also, a trust service may provide website authentication and preservation of created electronic signatures, certificates, and seals. It is handled by a trust service provider.

- European Union Trusted Lists (EUTL)

Evolution and legal implications

[edit]The eIDAS Regulation evolved from Directive 1999/93/EC, which set a goal that EU member states were expected to achieve in regards to electronic signing. Smaller European countries were among the first to start adopting digital signatures and identification, for example the first Estonian digital signature was given in 2002 and the first Latvian digital signature was given in 2006. Their experience has been used to develop a now EU-wide regulation, that became binding as law throughout the EU since the first of July, 2016.[15] Directive 1999/93/EC made EU member states responsible for creating laws that would allow them to meet the goal of creating an electronic signing system within the EU. The directive also allowed each member state to interpret the law and impose restrictions, thus preventing real interoperability, and leading toward a fragmented scenario.[16] In contrast with the 1999 directive, eIDAS ensures mutual recognition of the eID for authentication among member states,[17] thus achieving the goal of the Digital Single Market.

eIDAS provides a tiered approach of legal value. It requires that no electronic signature can be denied legal effect or admissibility in court solely for not being an advanced or qualified electronic signature.[18] Qualified electronic signatures must be given the same legal effect as handwritten signatures.[19]

For electronic seals (legal entities' version of signatures), probative value is explicitly addressed, as seals should enjoy the presumption of integrity and the correctness of the origin of the attached data.[20]

In June 2021, the Commission proposed an amendment and published a recommendation.[21][22][23]

Controversy

[edit]In 2023, a proposed change to the law was scrutinized as it would potentially enable EU governments to perform man-in-the-middle attacks, including encrypted communications.[24] The proposal was condemned by groups of cyber security researchers, NGOs, and civil society, as a threat to human rights, privacy, and dignity.[25][26][27][28] The proposal worked via the same mechanism as a 2019 attempt at mass surveillance in Kazakhstan.

At the core of this controversy is the second paragraph of the amendment to the article 45, which states:[29]

"Qualified certificates for website authentication referred to in paragraph 1 shall be recognised by web-browsers. [...] Web-browsers shall ensure support and interoperability with qualified certificates for website authentication referred to in paragraph 1, with the exception of enterprises, considered to be microenterprises and small enterprises in accordance with Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC in the first 5 years of operating as providers of web-browsing services."

Critics claimed that allowing certification authorities (CA) to issue certificates without going through auditing and vetting procedures put in place by browser vendors can jeopardize the security of the Internet as a whole and open the door for man-in-the-middle attacks.[30][31] This would possibly allow government mandated CAs to issue certificates for any domain name and use it for impersonation, and most critically, without browsers being able to remove them as trustworthy.[30] This is considered particularly concerning in countries with weaker rule of law, where state and state-connected actors would be able to use the law to spy on their own citizens for political repression and personal gain. There was additional concern that this allow private actors with state connections to gain access to and misuse the power for their own purposes.[25][27]

In the final draft, however, provisions were made to enable browser vendors to continue to implement security provisions that in practice would make this type of interception difficult to perform without being discovered.[32] Specifically, the final draft text states that:

- By way of derogation to paragraph 1 and only in case of substantiated concerns related to breaches of security or loss of integrity of an identified certificate or set of certificates, web-browsers may take precautionary measures in relation to that certificate or set of certificates.

which has been interpreted as allowing browser vendors to continue to use mechanisms such as certificate transparency to maintain browser security.[32] The statement of the European Commission on amendment of the article 45 clarifies this statement and denotes that through an agreement with browser vendors, no restriction are imposed on browsers' "own security policies".[33]

Design requirements

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Database information has to be linked to some kind of identity number. To certify that a person has the right to access some personal information involves several steps.

- Connecting a person to a number, which can be done through methods developed in one country, such as digital certificates.

- Connecting a number to specific information, done in databases.

- For eIDAS it is needed to connect the number used by a country having information, to the number used by the country issuing the digital certificates.

eIDAS has as minimum identity concept, the name and birth date. But in order to access more sensitive information, some kind of certification is needed that identity numbers issued by two countries refer to the same person.[34]

Vulnerabilities

[edit]In October 2019, two security flaws in eIDAS-Node (a sample implementation of the eID eIDAS Profile provided by the European Commission[35]) were discovered by security researchers; both vulnerabilities were patched for version 2.3.1 of eIDAS-Node.[36]

European Self-Sovereign Identity Framework

[edit]The European Union started[when?] creating an eIDAS compatible European Self-Sovereign Identity Framework (ESSIF),[citation needed] but in many countries, users need to be Google or Apple customers to use eIDAS services.

EUTL

[edit]The European Union Trusted Lists (EUTL) is a public list of over 200 active and legacy Trust Service Providers (TSPs) that are specifically accredited to deliver the highest levels of compliance with the EU eIDAS electronic signature regulation.[37]

See also

[edit]- China: China RealDID

- AdES and Long-term validation (LTV)

- PAdES

- Multi-factor authentication

- Single Digital Gateway

- USA: Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act and Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Turner, Dawn. "Understanding eIDAS". Cryptomathic. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market and repealing Directive 1999/93/EC". EUR-Lex. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ van Zijp, Jacques. "Is the EU ready for eIDAS?". Secure Identity Alliance. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Turner, Dawn M. "eIDAS from Directive to Regulation - Legal Aspects". Cryptomathic. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ a b Bender, Jens. "eIDAS Regulation: EID - Opportunities and Risks" (PDF). Bunde.de. Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ eIDAS in force, applies and exceptions on Europa.eu

- ^ Info on eIDAS, Connectis.

- ^ Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014

- ^ "eIDAS-Testbed successfully launched". www.eid.as. Retrieved 2024-06-19.

- ^ "A Digital Agenda For Europe". EUR-Lex. The European Commission. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ J.A., Ashiq. "The eIDAS Agenda: Innovation, Interoperability and Transparency". Cryptomathic. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ "European Digital Identity Wallet | Shaping Europe's digital future". digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu. 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2024-01-27.

- ^ "Towards principles and guidance for eID interoperability on online platforms" (PDF). Europa.eu. European Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Turner, Dawn M. "The Difference Between an Electronic Signature and a Digital Signature". Cryptomathic. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "Regulations, Directives and other acts". Europa.eu. The European Union. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ "Understanding eIDAS – All you ever wanted to know about the new EU Electronic Signature Regulation". Legal Technology. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ "A Big Step Toward the European Digital Single Market" (PDF). Inside Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Articles 25 (1) and definitions in article 3 (10) to 3 (12)

- ^ Article 25 (2)

- ^ Article 35 (2)

- ^ "Commission proposes a trusted and secure Digital Identity for all Europeans" (Press release). European Commission. 3 June 2021.

- ^ Procedure 2021/0136/COD on EUR-Lex, Procedure 2021/0136(COD) on the ŒIL

- ^ Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/946 of 3 June 2021 on a common Union Toolbox for a coordinated approach towards a European Digital Identity Framework on EUR-Lex

- ^ https://blog.mozilla.org/netpolicy/files/2023/11/eIDAS-Industry-Letter.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b https://last-chance-for-eidas.org/ [bare URL]

- ^ "EIDAS letter.PDF".

- ^ a b "Civil Society Experts Voice Concern as New EU Digital Identity Regulation Finalized".

- ^ "EU's Digital Identity Framework Endangers Browser Security". 15 December 2021.

- ^ Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 as regards establishing a framework for a European Digital Identity, 2021, retrieved 2024-10-20

- ^ a b Claburn, Thomas (2023-11-08). "Bad eIDAS: Europe ready to intercept, spy on your encrypted HTTPS connections". The Register. Retrieved 2024-10-20.

- ^ "EIDAS Letter 2022". 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b Hoepman, Jaap-Henk (2023-11-20). "Some observations on the final text of the European Digital Identity framework (eIDAS)". blog.xot.nl. Retrieved 2023-11-25.

- ^ "Texts adopted - European Digital Identity Framework - Thursday, 29 February 2024". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2024-10-20.

- ^ Hur skapar du en koppling mellan svenska och utländska eID:n? (in Swedish. Title translation: How to connect Swedish and foreign eID?)

- ^ "eIDAS-Node integration package". European Commission. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

The eIDAS-Node software contains the necessary modules to help Member States to communicate with other eIDAS-compliant counterparts in a centralised or distributed fashion.

- ^ Cimpanu, Catalin (29 October 2019). "Major vulnerability patched in the EU's eIDAS authentication system". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

Vulnerability would have allowed attackers to pose as any EU citizen or business.

- ^ https://helpx.adobe.com/document-cloud/kb/european-union-trust-lists.html [bare URL]

External links

[edit]- Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of 23 July 2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market on EUR-Lex

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1183 of 11 April 2024 amending Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 as regards establishing the European Digital Identity Framework on EUR-Lex

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch