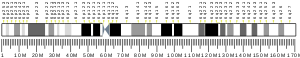

HSP90AB1

Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta also called HSP90beta is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HSP90AB1 gene.[5][6][7]

Function

[edit]HSP90AB1 is a molecular chaperone. Chaperones are proteins that bind to other proteins, thereby stabilizing them[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] in an ATP-dependent manner.[15] Chaperones stabilize new proteins during translation, mature proteins which are partially unstable but also proteins that have become partially denatured due to various kinds of cellular stress. In case proper folding or refolding is impossible, HSPs mediate protein degradation. They also have specialized functions, such as intracellular transport into organelles.

Classification

[edit]Human HSPs are classified into 5 major groups according to the HGNC:[16][17]

- HSP70

- DnaJ (HSP40)

- HSPB (small heat shock proteins)

- HSPC (HSP90)

- chaperonins

Chaperonins are characterized by their barrel-shaped structure with binding sites for client proteins inside the barrels.

The human HSP90 group consists of 5 members according to the HGNC:[17][18]

- HSP90AA1 (heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha, class A, member 1)

- HSP90AA3P (heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 3, pseudogene)

- HSP90AB1 (heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha, class B, member 1) (this protein)

- HSP90B1 (heat shock protein 90 kDA beta, member 1)

- TRAP1 (TNF receptor associated protein 1)

Whereas HSP90AA1 and HSP90AB1 are located primarily in the cytoplasm of the cells, HSP90B1 can be found in the endoplasmic reticulum and Trap1 in mitochondria.

Co-chaperones

[edit]Co-chaperones bind to HSPs and influence their activity, substrate (client) specificity and interaction with other HSPs.[14] For example, the co-chaperone CDC37 (cell division cycle 37) stabilizes the cell cycle regulatory proteins CDK4 (cyclin dependent kinase 4) and Cdk6.[19] Hop (HSP organizing protein) mediates the interaction between different HSPs, forming HSP70–HSP90 complexes.[20][21] TOM70 (translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane of ~70 kDa) mediates translocation of client proteins through the import pore into the mitochondrial matrix.[21][22]

Isoforms

[edit]Human HPS90AB1 shares 60% overall homology to its closest relative HSP90AA1.[23] Murine HSP90AB1 was cloned in 1987 based on homology of the corresponding Drosophila melanogaster gene.[24][25]

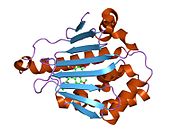

Protein structure

[edit]HSP90AB1 is active as homodimer, forming a V-shaped structure.[21][26][27][28][29][30] It consists of three major domains:

- N-terminal domain (NTD) containing the ATP binding site

- middle domain, primarily responsible for substrate binding

- C-terminal domain (CTD) which is the dimerization domain (base of the V).

Between these domains, there are short charged domains. Co-chaperones primarily bind to the NTD and CTD. The latter Co-chaperones usually contain a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain which binds to a MEEVD motif at the C-terminus of the HSP.[21][31] Inhibition of HSP90 activity by geldanamycin derivatives is based on their binding to the ATP binding site.[15]

Client proteins

[edit]Client proteins are steroid hormone receptors, kinases, ubiquitin ligases, transcription factors and proteins from many more families.[14][32][33] Examples of HSP90AB1 client proteins are p38MAPK/MAPK14 (mitogen activated protein kinase 14),[34] ERK5 (extracellular regulated kinase 5),[35] or the checkpoint kinase Wee1.[36]

Clinical significance

[edit]Cystic fibrosis (CF, mucoviscidosis) is a genetic disease with increased viscosity of various secretions leading to organ failure of lung, pancreas and other organs. It is caused in nearly all cases by a deletion of phenylalanine 508 of CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator). This mutation causes a maturation defect of this ion channel protein with increased degradation, mediated by HSPs. Deletion of the co-chaperone AHA1 (activator of heat shock 90kDa protein ATPase homolog 1) leads to stabilization of CFTR and opens up a perspective for a new therapy.[37]

Cancer

[edit]HSP90AB1 and its co-chaperones are frequently overexpressed in cancer cells.[38] They are able to stabilize mutant proteins thereby allowing survival and increased proliferation of cancer cells. This renders HSPs potential targets for cancer treatment.[39][40][41] In salivary gland tumors, expression of HSP90AA1 and HSP90AB1 correlates with malignancy, proliferation and metastasis.[42] The same is basically true for lung cancers where a correlation with survival was found.[43]

Notes

[edit]

The 2015 version of this article was updated by an external expert under a dual publication model. The corresponding academic peer reviewed article was published in Gene and can be cited as: Michael Haase, Guido Fitze (7 September 2015). "HSP90AB1: Helping the good and the bad". Gene. Gene Wiki Review Series. 575 (2 Pt 1): 171–186. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2015.08.063. ISSN 0378-1119. PMC 5675009. PMID 26358502. Wikidata Q38584468. |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000096384 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000023944 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Rebbe NF, Hickman WS, Ley TJ, Stafford DW, Hickman S (Sep 1989). "Nucleotide sequence and regulation of a human 90-kDa heat shock protein gene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (25): 15006–11. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63803-7. PMID 2768249.

- ^ Chen B, Piel WH, Gui L, Bruford E, Monteiro A (Dec 2005). "The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: insights into their divergence and evolution". Genomics. 86 (6): 627–37. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.012. PMID 16269234.

- ^ "NCBI Gene: HSP90AB1 heat shock protein 90 alpha family class B member 1". Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ Lindquist S (June 1986). "The heat-shock response". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 55 (1): 1151–1191. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. PMID 2427013. S2CID 42450279.

- ^ Gething MJ, Sambrook J (Jan 1992). "Protein folding in the cell". Nature. 355 (6355): 33–45. Bibcode:1992Natur.355...33G. doi:10.1038/355033a0. PMID 1731198. S2CID 4330003.

- ^ Craig EA, Gambill BD, Nelson RJ (Jun 1993). "Heat shock proteins: molecular chaperones of protein biogenesis". Microbiological Reviews. 57 (2): 402–14. doi:10.1128/MMBR.57.2.402-414.1993. PMC 372916. PMID 8336673.

- ^ Hartl FU (Jun 1996). "Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding". Nature. 381 (6583): 571–9. Bibcode:1996Natur.381..571H. doi:10.1038/381571a0. PMID 8637592. S2CID 4347271.

- ^ Johnson JL, Craig EA (Jul 1997). "Protein folding in vivo: unraveling complex pathways". Cell. 90 (2): 201–4. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80327-x. PMID 9244293. S2CID 16824153.

- ^ Wegele H, Müller L, Buchner J (2004). Hsp70 and Hsp90--a relay team for protein folding. Vol. 151. pp. 1–44. doi:10.1007/s10254-003-0021-1. ISBN 978-3-540-22096-1. PMID 14740253.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S (Jul 2010). "HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 11 (7): 515–28. doi:10.1038/nrm2918. PMID 20531426. S2CID 7842137.

- ^ a b Obermann WM, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU (Nov 1998). "In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 143 (4): 901–10. doi:10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. PMC 2132952. PMID 9817749.

- ^ "Gene group | HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee". HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC). Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ a b Kampinga HH, Hageman J, Vos MJ, Kubota H, Tanguay RM, Bruford EA, Cheetham ME, Chen B, Hightower LE (Jan 2009). "Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins". Cell Stress & Chaperones. 14 (1): 105–11. doi:10.1007/s12192-008-0068-7. PMC 2673902. PMID 18663603.

- ^ "HGNC HSP90 Group". HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC). Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Lamphere L, Fiore F, Xu X, Brizuela L, Keezer S, Sardet C, Draetta GF, Gyuris J (Apr 1997). "Interaction between Cdc37 and Cdk4 in human cells". Oncogene. 14 (16): 1999–2004. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201036. PMID 9150368. S2CID 25236893.

- ^ Chen S, Smith DF (Dec 1998). "Hop as an adaptor in the heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and hsp90 chaperone machinery". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (52): 35194–200. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.52.35194. PMID 9857057.

- ^ a b c d Scheufler C, Brinker A, Bourenkov G, Pegoraro S, Moroder L, Bartunik H, Hartl FU, Moarefi I (Apr 2000). "Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine". Cell. 101 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. PMID 10786835. S2CID 18200460.

- ^ Young JC, Hoogenraad NJ, Hartl FU (Jan 2003). "Molecular chaperones Hsp90 and Hsp70 deliver preproteins to the mitochondrial import receptor Tom70". Cell. 112 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01250-3. PMID 12526792.

- ^ Rebbe NF, Ware J, Bertina RM, Modrich P, Stafford DW (1987). "Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA for a member of the human 90-kDa heat-shock protein family". Gene. 53 (2–3): 235–45. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(87)90012-6. PMID 3301534.

- ^ Moore SK, Kozak C, Robinson EA, Ullrich SJ, Appella E (1987). "Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the murine hsp84 cDNA and chromosome assignment of related sequences". Gene. 56 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(87)90155-7. PMID 2445630.

- ^ Moore SK, Kozak C, Robinson EA, Ullrich SJ, Appella E (Apr 1989). "Murine 86- and 84-kDa heat shock proteins, cDNA sequences, chromosome assignments, and evolutionary origins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (10): 5343–51. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83551-7. PMID 2925609.

- ^ Prodromou C, Roe SM, Piper PW, Pearl LH (Jun 1997). "A molecular clamp in the crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of the yeast Hsp90 chaperone". Nature Structural Biology. 4 (6): 477–82. doi:10.1038/nsb0697-477. PMID 9187656. S2CID 38764610.

- ^ Stebbins CE, Russo AA, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl FU, Pavletich NP (Apr 1997). "Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent". Cell. 89 (2): 239–50. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. PMID 9108479. S2CID 5253110.

- ^ Harris SF, Shiau AK, Agard DA (Jun 2004). "The crystal structure of the carboxy-terminal dimerization domain of htpG, the Escherichia coli Hsp90, reveals a potential substrate binding site". Structure. 12 (6): 1087–97. doi:10.1016/j.str.2004.03.020. PMID 15274928.

- ^ Ali MM, Roe SM, Vaughan CK, Meyer P, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Prodromou C, Pearl LH (Apr 2006). "Crystal structure of an Hsp90-nucleotide-p23/Sba1 closed chaperone complex". Nature. 440 (7087): 1013–7. Bibcode:2006Natur.440.1013A. doi:10.1038/nature04716. PMC 5703407. PMID 16625188.

- ^ Shiau AK, Harris SF, Southworth DR, Agard DA (Oct 2006). "Structural Analysis of E. coli hsp90 reveals dramatic nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements". Cell. 127 (2): 329–40. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.027. PMID 17055434. S2CID 406855.

- ^ Young JC, Obermann WM, Hartl FU (Jul 1998). "Specific binding of tetratricopeptide repeat proteins to the C-terminal 12-kDa domain of hsp90". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (29): 18007–10. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.29.18007. PMID 9660753.

- ^ Tsaytler PA, Krijgsveld J, Goerdayal SS, Rüdiger S, Egmond MR (Nov 2009). "Novel Hsp90 partners discovered using complementary proteomic approaches". Cell Stress & Chaperones. 14 (6): 629–38. doi:10.1007/s12192-009-0115-z. PMC 2866955. PMID 19396626.

- ^ Echeverría PC, Bernthaler A, Dupuis P, Mayer B, Picard D (2011). "An interaction network predicted from public data as a discovery tool: application to the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machine". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e26044. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626044E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026044. PMC 3195953. PMID 22022502.

- ^ Bandyopadhyay S, Chiang CY, Srivastava J, Gersten M, White S, Bell R, Kurschner C, Martin C, Smoot M, Sahasrabudhe S, Barber DL, Chanda SK, Ideker T (Oct 2010). "A human MAP kinase interactome". Nature Methods. 7 (10): 801–5. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1506. PMC 2967489. PMID 20936779.

- ^ Erazo T, Moreno A, Ruiz-Babot G, Rodríguez-Asiain A, Morrice NA, Espadamala J, Bayascas JR, Gómez N, Lizcano JM (Apr 2013). "Canonical and kinase activity-independent mechanisms for extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) nuclear translocation require dissociation of Hsp90 from the ERK5-Cdc37 complex". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 33 (8): 1671–86. doi:10.1128/MCB.01246-12. PMC 3624243. PMID 23428871.

- ^ Aressy B, Jullien D, Cazales M, Marcellin M, Bugler B, Burlet-Schiltz O, Ducommun B (Sep 2010). "A screen for deubiquitinating enzymes involved in the G₂/M checkpoint identifies USP50 as a regulator of HSP90-dependent Wee1 stability". Cell Cycle. 9 (18): 3815–22. doi:10.4161/cc.9.18.13133. PMID 20930503.

- ^ Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, Riordan JR, Kelly JW, Yates JR, Balch WE (Nov 2006). "Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis". Cell. 127 (4): 803–15. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.043. PMID 17110338. S2CID 1457851.

- ^ McDowell CL, Bryan Sutton R, Obermann WM (Oct 2009). "Expression of Hsp90 chaperone [corrected] proteins in human tumor tissue". International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 45 (3): 310–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.06.012. PMID 19576239.

- ^ Den RB, Lu B (Jul 2012). "Heat shock protein 90 inhibition: rationale and clinical potential". Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 4 (4): 211–8. doi:10.1177/1758834012445574. PMC 3384095. PMID 22754594.

- ^ Jhaveri K, Taldone T, Modi S, Chiosis G (Mar 2012). "Advances in the clinical development of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitors in cancers". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1823 (3): 742–55. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.10.008. PMC 3288123. PMID 22062686.

- ^ Hong DS, Banerji U, Tavana B, George GC, Aaron J, Kurzrock R (Jun 2013). "Targeting the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 (HSP90): lessons learned and future directions". Cancer Treatment Reviews. 39 (4): 375–87. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.10.001. PMID 23199899.

- ^ Wang G, Gu X, Chen L, Wang Y, Cao B, E Q (Apr 2013). "Comparison of the expression of 5 heat shock proteins in benign and malignant salivary gland tumor tissues". Oncology Letters. 5 (4): 1363–1369. doi:10.3892/ol.2013.1166. PMC 3629267. PMID 23599795.

- ^ Biaoxue R, Xiling J, Shuanying Y, Wei Z, Xiguang C, Jinsui W, Min Z (Aug 2012). "Upregulation of Hsp90-beta and annexin A1 correlates with poor survival and lymphatic metastasis in lung cancer patients". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 31 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-31-70. PMC 3444906. PMID 22929401.

Further reading

[edit]- Hoffmann T, Hovemann B (Dec 1988). "Heat-shock proteins, Hsp84 and Hsp86, of mice and men: two related genes encode formerly identified tumour-specific transplantation antigens". Gene. 74 (2): 491–501. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(88)90182-5. PMID 2469626.

- Lees-Miller SP, Anderson CW (Feb 1989). "Two human 90-kDa heat shock proteins are phosphorylated in vivo at conserved serines that are phosphorylated in vitro by casein kinase II". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (5): 2431–7. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)81631-9. PMID 2492519.

- Rebbe NF, Ware J, Bertina RM, Modrich P, Stafford DW (1987). "Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA for a member of the human 90-kDa heat-shock protein family". Gene. 53 (2–3): 235–45. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(87)90012-6. PMID 3301534.

- Tang PZ, Gannon MJ, Andrew A, Miller D (Nov 1995). "Evidence for oestrogenic regulation of heat shock protein expression in human endometrium and steroid-responsive cell lines". European Journal of Endocrinology. 133 (5): 598–605. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1330598. PMID 7581991.

- Nemoto T, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Ota M, Takagi T, Yokoyama K (Oct 1995). "Mechanism of dimer formation of the 90-kDa heat-shock protein". European Journal of Biochemistry. 233 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.001_1.x. PMID 7588731.

- Takahashi I, Tanuma R, Hirata M, Hashimoto K (Feb 1994). "A cosmid clone at the D6S182 locus on human chromosome 6p12 contains the 90-kDa heat shock protein beta gene (HSP90 beta)". Mammalian Genome. 5 (2): 121–2. doi:10.1007/BF00292342. PMID 8180474. S2CID 30075426.

- Ji H, Reid GE, Moritz RL, Eddes JS, Burgess AW, Simpson RJ (1997). "A two-dimensional gel database of human colon carcinoma proteins". Electrophoresis. 18 (3–4): 605–13. doi:10.1002/elps.1150180344. PMID 9150948. S2CID 25454450.

- Yano M, Naito Z, Yokoyama M, Shiraki Y, Ishiwata T, Inokuchi M, Asano G (Mar 1999). "Expression of hsp90 and cyclin D1 in human breast cancer". Cancer Letters. 137 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00338-3. PMID 10376793.

- Sato S, Fujita N, Tsuruo T (Sep 2000). "Modulation of Akt kinase activity by binding to Hsp90". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (20): 10832–7. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710832S. doi:10.1073/pnas.170276797. PMC 27109. PMID 10995457.

- Gisler SM, Stagljar I, Traebert M, Bacic D, Biber J, Murer H (Mar 2001). "Interaction of the type IIa Na/Pi cotransporter with PDZ proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (12): 9206–13. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008745200. PMID 11099500. S2CID 35476933.

- Wiemann S, Weil B, Wellenreuther R, Gassenhuber J, Glassl S, Ansorge W, Böcher M, Blöcker H, Bauersachs S, Blum H, Lauber J, Düsterhöft A, Beyer A, Köhrer K, Strack N, Mewes HW, Ottenwälder B, Obermaier B, Tampe J, Heubner D, Wambutt R, Korn B, Klein M, Poustka A (Mar 2001). "Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs". Genome Research. 11 (3): 422–35. doi:10.1101/gr.GR1547R. PMC 311072. PMID 11230166.

- King FW, Wawrzynow A, Höhfeld J, Zylicz M (Nov 2001). "Co-chaperones Bag-1, Hop and Hsp40 regulate Hsc70 and Hsp90 interactions with wild-type or mutant p53". The EMBO Journal. 20 (22): 6297–305. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.22.6297. PMC 125724. PMID 11707401.

- Bouhouche-Chatelier L, Chadli A, Catelli MG (Oct 2001). "The N-terminal adenosine triphosphate binding domain of Hsp90 is necessary and sufficient for interaction with estrogen receptor". Cell Stress & Chaperones. 6 (4): 297–305. doi:10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0297:tntatb>2.0.co;2 (inactive 2024-04-11). PMC 434412. PMID 11795466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - Sato N, Yamamoto T, Sekine Y, Yumioka T, Junicho A, Fuse H, Matsuda T (Jan 2003). "Involvement of heat-shock protein 90 in the interleukin-6-mediated signaling pathway through STAT3". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 300 (4): 847–52. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02941-8. hdl:2115/28121. PMID 12559950. S2CID 1460250.

- Wu JM, Xiao L, Cheng XK, Cui LX, Wu NH, Shen YF (Dec 2003). "PKC epsilon is a unique regulator for hsp90 beta gene in heat shock response". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (51): 51143–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305537200. PMID 14532285.

- Nagaraja GM, Kandpal RP (Jan 2004). "Chromosome 13q12 encoded Rho GTPase activating protein suppresses growth of breast carcinoma cells, and yeast two-hybrid screen shows its interaction with several proteins". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 313 (3): 654–65. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.001. PMID 14697242.

- Bouwmeester T, Bauch A, Ruffner H, Angrand PO, Bergamini G, Croughton K, Cruciat C, Eberhard D, Gagneur J, Ghidelli S, Hopf C, Huhse B, Mangano R, Michon AM, Schirle M, Schlegl J, Schwab M, Stein MA, Bauer A, Casari G, Drewes G, Gavin AC, Jackson DB, Joberty G, Neubauer G, Rick J, Kuster B, Superti-Furga G (Feb 2004). "A physical and functional map of the human TNF-alpha/NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (2): 97–105. doi:10.1038/ncb1086. PMID 14743216. S2CID 11683986.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch