High Bridge (New York City)

High Bridge | |

|---|---|

View of the closed bridge from Highbridge Park in 2008 | |

| Coordinates | 40°50′32″N 73°55′49″W / 40.842308°N 73.930277°W |

| Carries | Pedestrians and bicycles |

| Crosses | Harlem River |

| Locale | Manhattan and the Bronx, New York City |

| Owner | Government of New York City |

| Maintained by | NYC Parks |

| Preceded by | Alexander Hamilton Bridge |

| Followed by | Macombs Dam Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Arch bridge |

| Total length | 1,450 ft (440 m)[1] |

| Height | 140 ft (43 m)[1] |

| History | |

| Opened | 1848 (aqueduct) 1864 (walkway) 2015 (dedicated walkway) |

| Rebuilt | 1927 |

| Closed | 1949 (water supply) c.1970–2015 |

| Statistics | |

High Bridge | |

New York City Landmark No. 0639 | |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001560 |

| NYSRHP No. | 06101.006666 |

| NYCL No. | 0639 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 4, 1972 |

| Designated NYSRHP | June 23, 1980[2] |

| Designated NYCL | November 10, 1970 |

| Location | |

| |

The High Bridge (originally the Aqueduct Bridge) is a steel arch bridge connecting the New York City boroughs of the Bronx and Manhattan. Rising 140 ft (43 m) over the Harlem River, it is the city's oldest bridge, having opened as part of the Croton Aqueduct in 1848. The eastern end is located in the Highbridge section of the Bronx near the western end of West 170th Street, and the western end is located in Highbridge Park in Manhattan, roughly parallel to the end of West 174th Street.[3]

High Bridge was originally completed in 1848 with 16 individual stone arches. In 1928, the five that spanned the Harlem River were replaced by a single 450-foot (140 m) steel arch. The bridge was closed to all traffic from around 1970 until its restoration, which began in 2009. The bridge was reopened to pedestrians and bicycles on June 9, 2015.

The bridge is operated and maintained by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The High Bridge was part of the first reliable and plentiful water supply system in New York City. As the City was devastated by cholera in 1832 and the Great Fire in 1835, the inadequacy of the water system of wells-and-cisterns became apparent. Numerous corrective measures were examined.[4] In the final analysis, only the Croton River in northern Westchester County was found to carry water sufficient in quantity and quality to serve the City. The delivery system was begun in 1837, and was completed in 1848.[4]

The Old Croton Aqueduct was the first of its kind ever constructed in the United States. The innovative system used a classic gravity feed, dropping 13 inches (330 mm) per mile, or about 1/4" per 100' (~0.02%)[5] and running 41 miles (66 km) into New York City through an enclosed masonry structure crossing ridges, valleys, and rivers. University Avenue was later built over the southernmost mainland portion of the aqueduct, leading to the bridge. Though the carrying capacity was enlarged in 1861–1862 with a larger tube, the bridge became obsolete in 1910 with the opening of the New Croton Aqueduct.[4] In the 1920s, the bridge's masonry arches were declared a hazard to ship navigation by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, and the City considered demolishing the entire structure. Local organizations called to preserve the historic bridge, and, in 1927, five of the original arches across the river were replaced by a single steel span, while the remaining arches were retained.[1]

Construction

[edit]Originally designed as a stone arch bridge, the High Bridge had the appearance of a Roman aqueduct. Construction on the bridge was started in 1837, and was completed in 1848 as part of the Croton Aqueduct, which carried water from the Croton River to supply the then burgeoning city of New York some 10 miles (16 km) to the south. The bridge has a height of 140 ft (43 m) above the 620-foot-wide (190 m) Harlem River, with a total length of 1,450 ft (440 m).[1] The design of the bridge was originally awarded to Major David Bates Douglass, who was fired from the project.[6] The design then fell to the aqueduct's engineering team, led by John B. Jervis. James Renwick Jr., who later went on to design the landmark Saint Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, participated in the design.

The Croton Aqueduct had to cross the Harlem River at some point, and the method was a major design decision. A tunnel under the river was considered, but tunneling technology was in its infancy at the time, and the uncertainty of pursuing this option led to its rejection. This left a bridge, with the Water Commission, engineers and the public split between a low bridge and a high bridge. A low bridge would have been simpler, faster, and cheaper to construct. When concerns were raised to the New York Legislature that a low bridge would obstruct passage along the Harlem River to the Hudson River, a high bridge was ultimately chosen.

The contractors for the project were George Law, Samuel Roberts and Arnold Mason.[7] Mason had prior engineering experience working on the Erie Canal and the Morris Canal.[8]

Post-opening

[edit]

In 1864, a pedestrian walkway was built across the High Bridge. The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation which is responsible for its maintenance, described the walkway as the bridge's contemporary High Line.[9]

As part of a U.S. federal government initiative to improve navigation along the Harlem River, in 1923, a New York City Board of Estimate committee recommended demolishing the High Bridge. The bridge's stones would have been reused for a bridge carrying Riverside Drive above Dyckman Street in Inwood, Manhattan.[10] In 1928, the five masonry arches that spanned the river were demolished and replaced with a single steel arch of about 450 feet (140 m).[1] Of the masonry arches of the original 1848 bridge, only one survives on the Manhattan side, while nine survive on the Bronx side.

Use of the structure to deliver water to Manhattan ceased on December 15, 1949.

By 1954, The New York Times reported that the commissioner of the Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity said that "the bridge entailed serious problems of maintenance and vandalism".[11] Robert Moses agreed to take responsibility for the bridge, which was transferred to the Parks Department in 1955.[12] There were incidents, in 1957 and 1958, of pedestrians throwing sticks, stones, and bricks from the bridge, seriously injuring passengers on Circle Line tour boats which passed under the bridge.[13] The bridge was closed by 1970, when high crime and fiscal crisis led to the contraction of many city services and public spaces.[4] However, a reporter for The New York Times wrote that when he had tried to walk across the bridge in 1968, it was closed.[14] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the High Bridge as a city landmark on November 15, 1970.[15][16]

In November 2006, the Department of Parks and Recreation announced that the bridge would reopen to pedestrians in 2009.[17] This date was repeatedly put off. A $20 million renovation project would include strengthening the arch, improving staircases, cameras on both ends of the bridge, and boat beacon lights among other features.[18]

In 2009, preliminary planning, funded by PlaNYC, began for restoring the High Bridge.[17] The High Bridge Coalition raised funds and public awareness to restore High Bridge to pedestrian and bicycle traffic, joining the Highbridge Parks in both Manhattan and the Bronx that together cover more than 120 acres (0.49 km2) of parkland, and providing a link in New York's greenway system.[19] In early 2010, a contract was signed with Lichtenstein Consulting Engineers and Chu & Gassman Consulting Engineers (MEP sub-consultant) to provide designs for the restored bridge.[20]

On January 11, 2013, the mayor's office announced the bridge would reopen for pedestrian traffic by 2014,[21] but in August 2014, the open was postponed to spring of 2015.[22] In May 2015, the Parks Department announced a July opening[23] and a July 25 festival.[24] The ribbon was cut for the restored bridge at about 11:30 a.m. on June 9, 2015, with the bridge open to the general public at noon.[21][25][26] The High Bridge was illuminated at night following its restoration.[27]

High Bridge Water Tower

[edit]The High Bridge Water Tower, in Highbridge Park between West 173rd and 174th streets, on top of the ridge on the Manhattan side of High Bridge, was built in 1866–1872 to help meet the ever-increasing demands on the city's water system. The 200-foot (61 m) octagonal tower, which was authorized by the State Legislature in 1863, was designed by John B. Jervis, the engineer who supervised the building of the High Bridge Aqueduct. Water was pumped up 100 feet (30 m) to a 7-acre (2.8 ha) reservoir next to the tower – now the site of a play center and public pool built in 1934–1936 – which then provided water to be lifted to the tower's 47,000 US gallons (180 m3) tank. This "high service" improved the water system's gravity pressure, necessary because of the increased use of flush toilets.[28][29][30]

The High Bridge system reached its full capacity by 1875.[30] With the opening of the New Croton Aqueduct in 1890, the High Bridge system became less relied upon; during World War I, it was completely shut down when sabotage was feared.[30] In 1949, the tower was removed from service,[28][30] and a carillon, donated by the Altman Foundation, was installed in 1958.[30]

The tower's cupola was damaged by an arson fire in 1984. It was reconstructed, and the tower's load-bearing exterior stonework – which Jervis designed in a mixture of Romanesque Revival and neo-Grec styles – was cleaned and restored in 1989–1990 by the William A. Hall Partnership.[29][30] Christopher Gray has said of the tower's design that "Its rock-faced granite gives the tower a chunky, fortified appearance, as if it were a lookout for a much larger castle complex that was never built.... The granite is competently handled, but the details are not very inspired or elegant. The tower is more picturesque than beautiful."[30]

The interior of the tower, which was never open to the public, features a wide well-detailed iron spiral staircase with six large landings and paired windows.[30]

The High Bridge Water Tower was designated a New York City landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1967.[28] The High Bridge Water Tower underwent a 10-year, $5 million renovation during the 2010s and reopened to the public in November 2021.[31][32] After the water tower reopened, NYC Parks began hosting free tours of the structure.[33]

Gallery

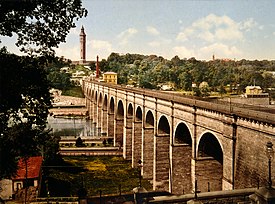

[edit]- A print from 1900, showing original stone arches

- The transition from the steel arch over the Harlem River to the stone arches over the Major Deegan Expressway

- Three Harlem River bridges: High Bridge nearest; Alexander Hamilton Bridge; and Washington Bridge, farthest. Washington Heights on left; the Bronx on right

- Interior staircase of the High Bridge Water Tower

- Walkway plaques

- High Bridge Construction (1848)

- The High Bridge (1839–1848)

- Steel Arch (1927–1928)

- Changing City (1934–1936)

- High Bridge Restoration (2015)

See also

[edit]- Highbridge Reservoir

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in New York (state)

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan above 110th Street

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in the Bronx

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan above 110th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in the Bronx

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c d e "Croton Water Supply System". ASCE Metropolitan Section. American Society of Civil Engineers. n.d. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ Ramey, Corinne (June 8, 2015). "The Grass Is Greener on the Other Side". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Dwyer, Jim (June 4, 2015). "A Stunning Link to New York's Past Makes a Long-Awaited Return". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ "An Engineering Marvel". Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Eldredge, Niles and Horenstein, Sidney (2014). Concrete Jungle: New York City and Our Last Best Hope for a Sustainable Future. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-520-27015-2.

- ^ Hough, Franklin Benjamin. Gazetteer of the State of New York: Embracing a Comprehensive Account of the History and Statistics of the State, with Geological and Topographical Descriptions, and Recent Statistical Tables, 1872, page 416

- ^ Journal of the Western Society of Engineers, Vols. 43-45, page 4

- ^ "History of the High Bridge: NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ "High Bridge to Go; Replica to Be Built; Historic Span's Stone Will Be Used and Architecture Followed in New Viaduct". The New York Times. June 19, 1923. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ O'Kane, Lawrence (July 8, 1954). "Span is 'Swapped' on City Boat Ride; Top Officials, Viewing Harlem River Drive From Tug, Get Into Deal for High Bridge". The New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ "River Landmarks to Be Park Units; Plan Board Transfers Span and Tower at High Bridge From Water Department". The New York Times. January 20, 1955. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ "Boys Stone Boat, Hurt Sight-seers; 4 on Excursion Craft Hit as Youths Hurl Objects From High Bridge in Bronx". The New York Times. April 21, 1958. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ Bird, David (October 27, 1968). "A 32-Mile-Long Swath of Green From the Country to the City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Mansions and Span Ruled Landmarks". The New York Times. November 16, 1970. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ "Landmark Decisions". New York Daily News. November 16, 1970. p. 5. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ a b "High Bridge PlaNYC Project Overview". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ Hughes, C. J. (May 20, 2007). "Living In: High Bridge, the Bronx - Home of the Bronx Roar". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ "The High Bridge & Highbridge Parks" (PDF). High Bridge Coalition. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Aaron, Brad (February 11, 2010). "High Bridge Restoration Off and Running". Streetsblog New York City. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Artz, Kristen (January 11, 2013). "Mayor Bloomberg Breaks Ground On Project To Restore The High Bridge Over Harlem River And Reopen It To Pedestrians And Bicyclists". NYC, the official website of the City of New York. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Clarke, Erin (August 28, 2014). "High Bridge's Reopening Slated for Spring". NY1. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "The High Bridge Reconstruction Project". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ "High Bridge Events". NYC Parks. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ "High Bridge reopens to bikes, pedestrians" Archived July 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine MyFox TV

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa W. (June 10, 2015). "High Bridge Reopens After More Than 40 Years". The New York Times. p. A19. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ "Light Bridges the Gap: High Bridge Restoration". Horton Lees Brogden Lighting Design. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 566. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gray, Christopher (October 9, 1988). "Streetscapes: The High Bridge Water Tower; Fire-Damaged Landmark To Get $900,000 Repairs". The New York Times.

- ^ "NYC's historic High Bridge Water Tower in Washington Heights reopening soon after more than a decade". ABC7 New York. October 27, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ Rahmanan, Anna (October 28, 2021). "You can tour this historic NYC tower for the first time in a decade". Time Out New York. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ Sheidlower, Noah (March 7, 2022). "Go Inside NYC's High Bridge Water Tower". Untapped New York. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch